- University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA

- Audie L. Murphy Memorial VA Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, USA

Correspondence Address:

Michael McGinity

University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, USA

Audie L. Murphy Memorial VA Hospital, San Antonio, Texas, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.202132

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Michael McGinity, Huma Siddiqui, Gulpreet Singh, Fermin Tio, Ahmed Shakir. Primary atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in the adult spine. 14-Mar-2017;8:34

How to cite this URL: Michael McGinity, Huma Siddiqui, Gulpreet Singh, Fermin Tio, Ahmed Shakir. Primary atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in the adult spine. 14-Mar-2017;8:34. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/primary-atypical-teratoid-rhabdoid-tumor-in-the-adult-spine/

Abstract

Background:Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) is a highly aggressive tumor of the central nervous system (WHO grade IV), which is most frequently found intracranially in young children and infants. Only three prior cases of primary ATRT involving the adult spine were found following a literature review, and the average survival for these patients was only 20 postoperative months.

Case Description:A 43 year-old female presented with an acute exacerbation of chronic neck pain. While awaiting magnetic resonance (MR) studies of the cervical spine, she was found pulseless in her room. Although cardiopulmonary resuscitation was successful, she was found to be quadriplegic. The subsequent cervical MR imaging revealed a C1-3 intradural, extramedullary ventrolateral mass, markedly compressing the upper cervical spinal cord. Following successful surgical resection of the lesion, which proved pathologically to be an ATRT, she was treated with a full course of fractionated radiation therapy. Over the successive 6-month period, her neurological examination continued to improve to 4-/5 functional strength in her upper extremities, however, remained with 2/5 nonfunctional strength in her legs.

Conclusions:ATRT involving the adult spine are rare and may often be misdiagnosed. This study points out that aggressive surgery followed by radiation therapy may improve outcome.

Keywords: ATRT tumor, atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor, cervical laminectomy, cervical spine surgery, INI1, neurosurgery

INTRODUCTION

Primary atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) rarely involves the adult spine. We present the case of a 43-year-old female with an ATRT found at the C1-3 level of the cervical spine. It was intradural/extramedullary in location and was completely excised after performing multilevel laminectomies. The patient continued to do well for 6 months following surgery and radiation therapy. Here, we review the three other adult spinal cases of ATRT reported in the literature, and discussed their average survival of only 20 months.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Presentation and surgery

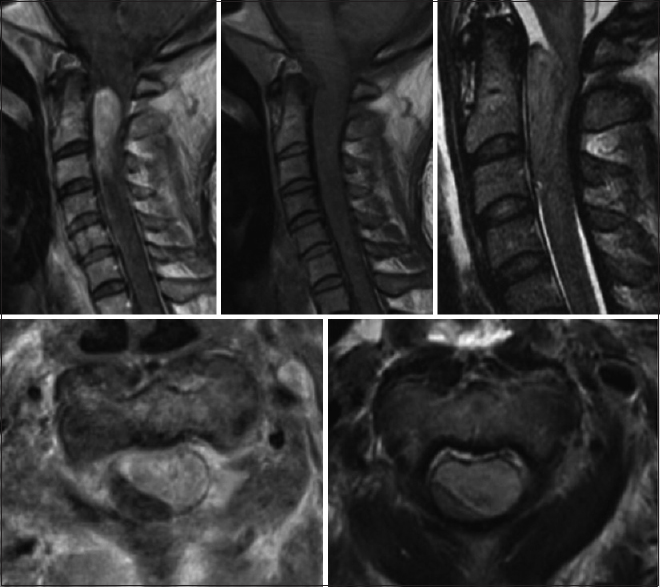

A 43-year-old female with a significant history of chronic neck pain, migraine, and coronary artery disease presented acutely with marked exacerbation of chronic neck pain and headache. When initially seen, she was neurologically intact. While awaiting magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain and cervical spine, she was found unresponsive and pulseless and required full cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The cervical MRI documented a C1-3 intradural, extramedullary, ventrolateral mass nearly filling the spinal canal resulting in severe compression of the upper cervical cord. Marked cord edema, seen on the T2 image, was present from C5 through the medulla [

Postoperative course

Immediately postoperatively, the patient remained quadriplegic. However, on the postoperative day 12, she began moving the digits of the right hand and toes on the right side. She continued to exhibit poor respiratory effort and remained intubated for 14 days, subsequently requiring tracheostomy and gastrostomy. After 36 days of inpatient care, the patient was discharge to an inpatient rehabilitation facility. Upon discharge, she began a course of 28 fractions of radiation therapy for a total dose of 5040 cGy; she finished the radiation therapy 7 weeks later. Because of low performance status, she was no deemed a suitable candidate for chemotherapy.

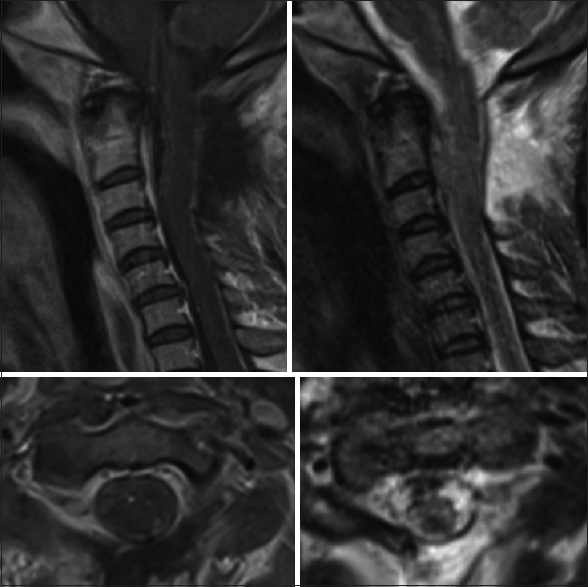

Twelve weeks postoperatively, she had regained antigravity strength in both the upper extremities and was able to feed herself. She also demonstrated gross movement in both the lower extremities in all muscle groups, however, this was still deemed nonfunctional strength. The subsequent cervical MRI at four months postopertive revealed no recurrent disease. At 6 months, the patient remained in a nursing home with a stable neurological exam.

Pathology

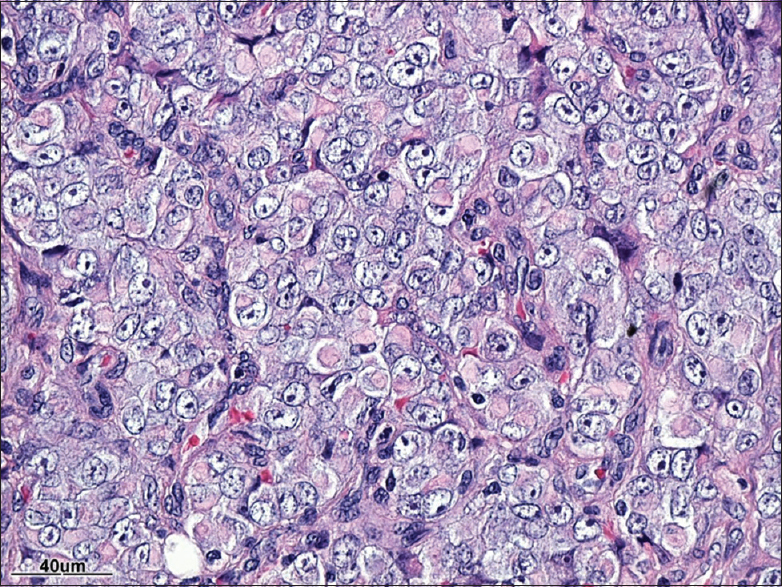

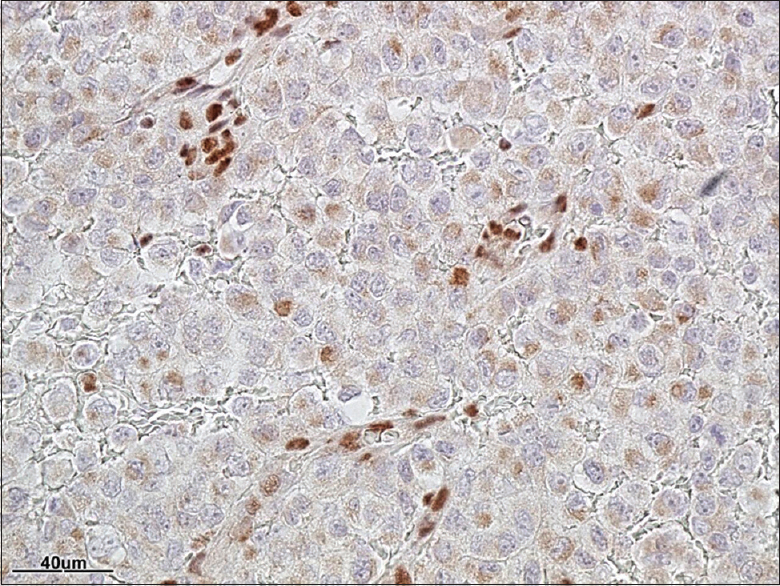

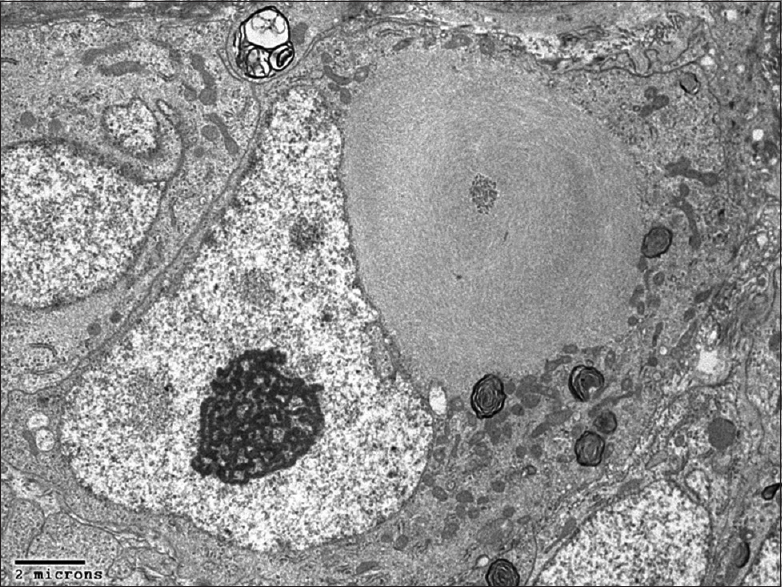

[Figures

DISCUSSION

ATRT are highly aggressive lesions of the central nervous system (WHO grade IV), most frequently found intracranially in infants and young children.[

Establishing the pathological diagnosis of ATRT

The pathological diagnosis of ATRT entails the identification of sheet of rhabdoid cells and inactivation of the INI1 (SMARCB1) gene.[

Imaging of ATRT

Imaging characteristics have been shown to be highly inconsistent including variable enhancement and cystic patterns.[

Three prior spinal cases of ATRT in adults

To our knowledge, there are only three cases of primary ATRT that involve the adult spine.[

CONCLUSION

ATRT only very rarely involves the adult spine, and must be differentiated from primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). Owing to the aggressive nature of this disease, further reporting of this disease process is necessary for early tumor resection and adequate utilization of adjunctive treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bruch LA1, Hill DA, Cai DX, Levy BK, Dehner LP, Perry A. A role for fluorescence in situ hybridization detection of chromosome 22q dosage in distinguishing atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors from medulloblastoma/central primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Human Pathol. 2001. 32: 156-62

2. Horn M, Schlote W, Lerch KD, Steudel WI, Harms D, Thomas E. Malignant rhabdoid tumor: Primary intracranial manifestation in an adult. Acta Neuropathol. 1992. 83: 445-8

3. Margol AS, Judkins AR. Pathology and diagnosis of SMARCB1-deficient tumors. Cancer Genet. 2014. 207: 358-64

4. Rorke LB, Packer RJ, Biegel JA. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of infancy and childhood: Definition of an entity. J Neurosurg. 1996. 85: 56-65

5. Rorke LB, Biegel JA, Kleihues P, Cavenee WK.editors. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. The WHO classification of tumors: Pathology and genetics or tumors of the nervous system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. p. 145-8

6. Sinha P, Ahmad M, Varghese A, Parekh T, Ismail A, Chakrabarty A. Atypical teratoid rhaboid tumor of the spine: Report of a case and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2015. 24: S472-84

7. Warmuth-Metz M, Bison B, Dannemann-Stern E, Kortmann R, Rutkowski S, Pietsch T. CT and MR imaging in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors of the central nervous system. Neuroradiology. 2008. 50: 447-52

8. Zarovnaya E, Pallatroni H, Hug E, Ball PA, Cromwell LD, Pipas JM. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the spine in an adult: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2007. 84: 49-55