- Neurosurgery, Department of Surgical Specialties, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Treatment of Craniofacial Anomalies Center, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Correspondence Address:

Bruna Cavalcante de Sousa, Neurosurgery, Department of Surgical Specialties, Pedro Ernesto University Hospital, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1029_2023

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Bruna Cavalcante de Sousa1, Pedro Henrique Costa Ferreira-Pinto1, Domênica Baroni Coelho de Oliveira Ferreira1, Eduardo Pantoja Bastos2, Marcio Lima Leal Arnaut Junior2, Bruno Santos de Barros Dias2, Thiago Schneider2, Valéria Claro2, Henrique Pessoa Ladvocat Cintra2, Maud Parise1, Eduardo Mendes Correa1, Thaina Zanon Cruz1, Wellerson Novaes da Silva1, Flavio Nigri1. Isolated hypertelorism: Late surgical correction using the box osteotomy technique. 26-Apr-2024;15:145

How to cite this URL: Bruna Cavalcante de Sousa1, Pedro Henrique Costa Ferreira-Pinto1, Domênica Baroni Coelho de Oliveira Ferreira1, Eduardo Pantoja Bastos2, Marcio Lima Leal Arnaut Junior2, Bruno Santos de Barros Dias2, Thiago Schneider2, Valéria Claro2, Henrique Pessoa Ladvocat Cintra2, Maud Parise1, Eduardo Mendes Correa1, Thaina Zanon Cruz1, Wellerson Novaes da Silva1, Flavio Nigri1. Isolated hypertelorism: Late surgical correction using the box osteotomy technique. 26-Apr-2024;15:145. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12872

Abstract

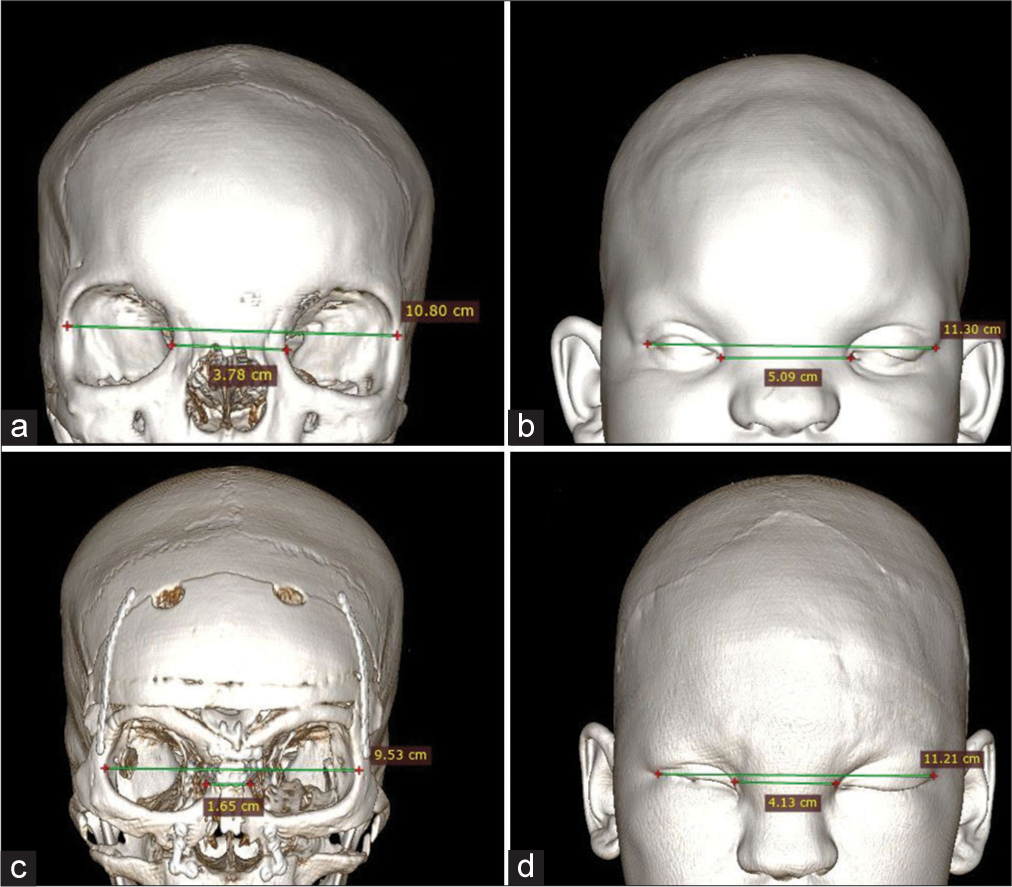

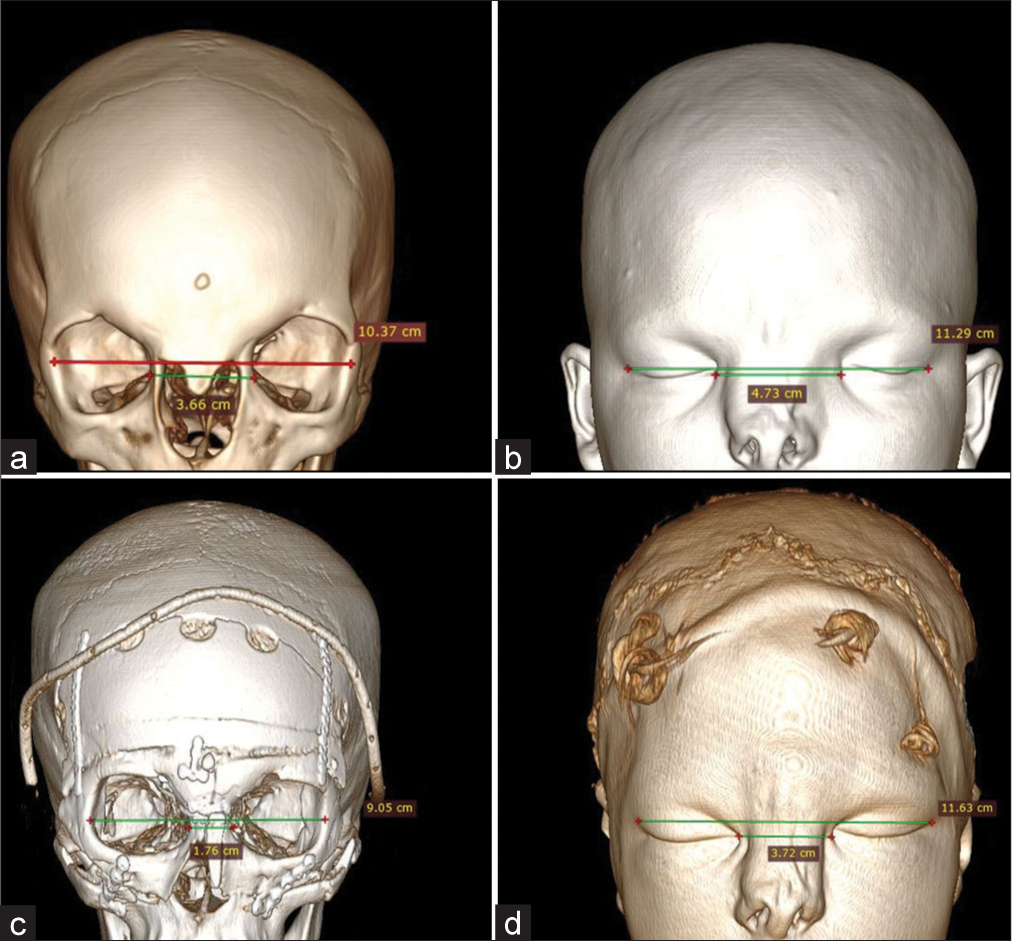

Background: Orbital hypertelorism is a rare congenital condition caused by craniofacial malformations. It consists of complete orbital lateralization, characterized by an increase in distance (above the 95th percentile) of the inner canthal (ICD), outer canthal, and interpupillary distances. It can be approached surgically, and the main techniques are box osteotomy and facial bipartition. The surgical procedure is usually performed before the age of 8. We describe here two patients who underwent late surgical correction using the box osteotomy technique.

Case Description: Patient 1: A 13-year-old female presenting isolated hypertelorism with 5 cm ICD and left eye amblyopia. Patient 2: A 15-year-old female with orbital hypertelorism, 4.6 cm ICD, and nasal deformity. Both patients underwent orbital translocation surgery and had no neurological disorders.

Conclusion: The article reports two cases of isolated hypertelorism treated late with the box osteotomy technique. Both surgeries were successful, with no postoperative complications. It appears that it is possible to obtain good surgical results even in patients who have not been able to undergo surgery previously.

Keywords: Box osteotomy, Hypertelorism, Late correction, Orbital translocation

INTRODUCTION

Orbital hypertelorism, also known as hypertelorism, is a congenital condition first described in 1924.[

This congenital anomaly can be addressed surgically, and the two main techniques are box osteotomy and facial bipartition.[

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Case 1

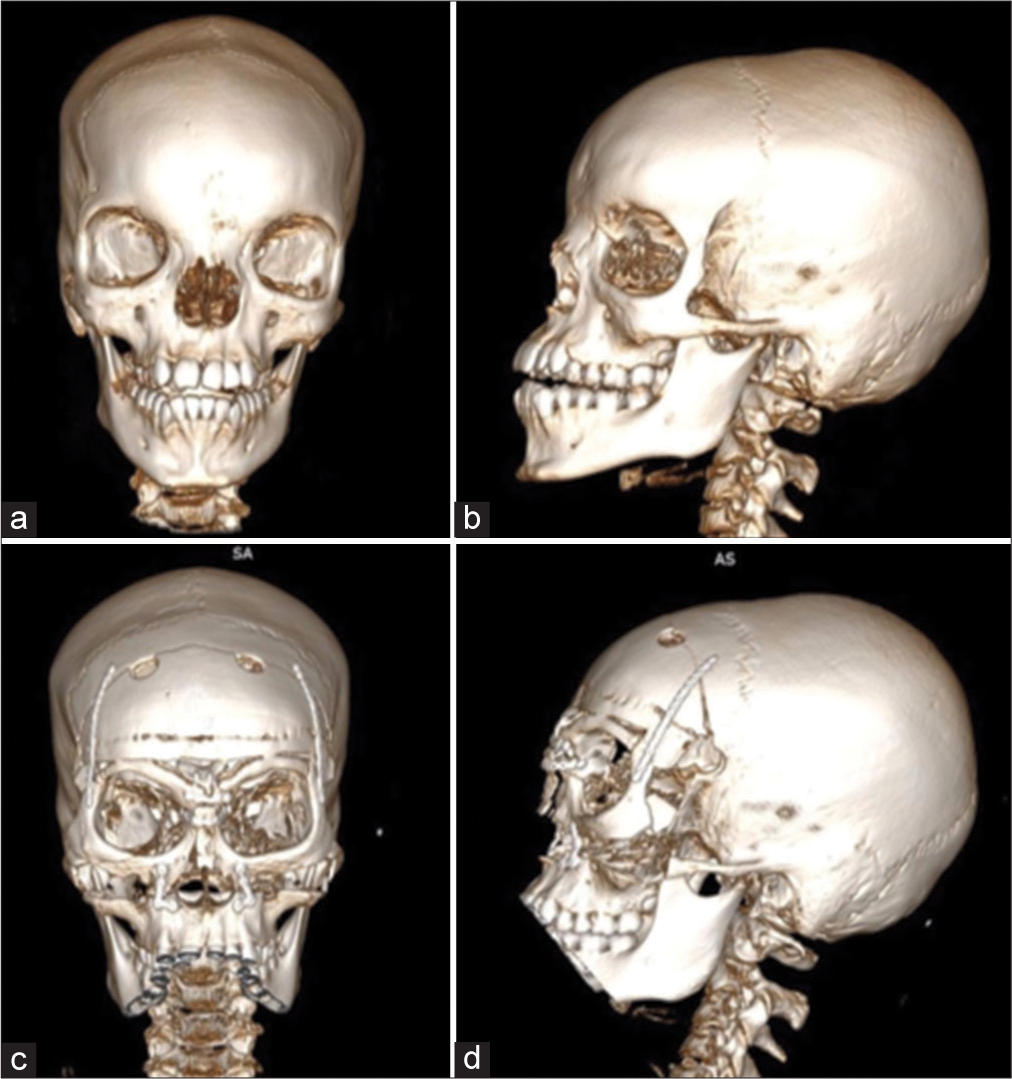

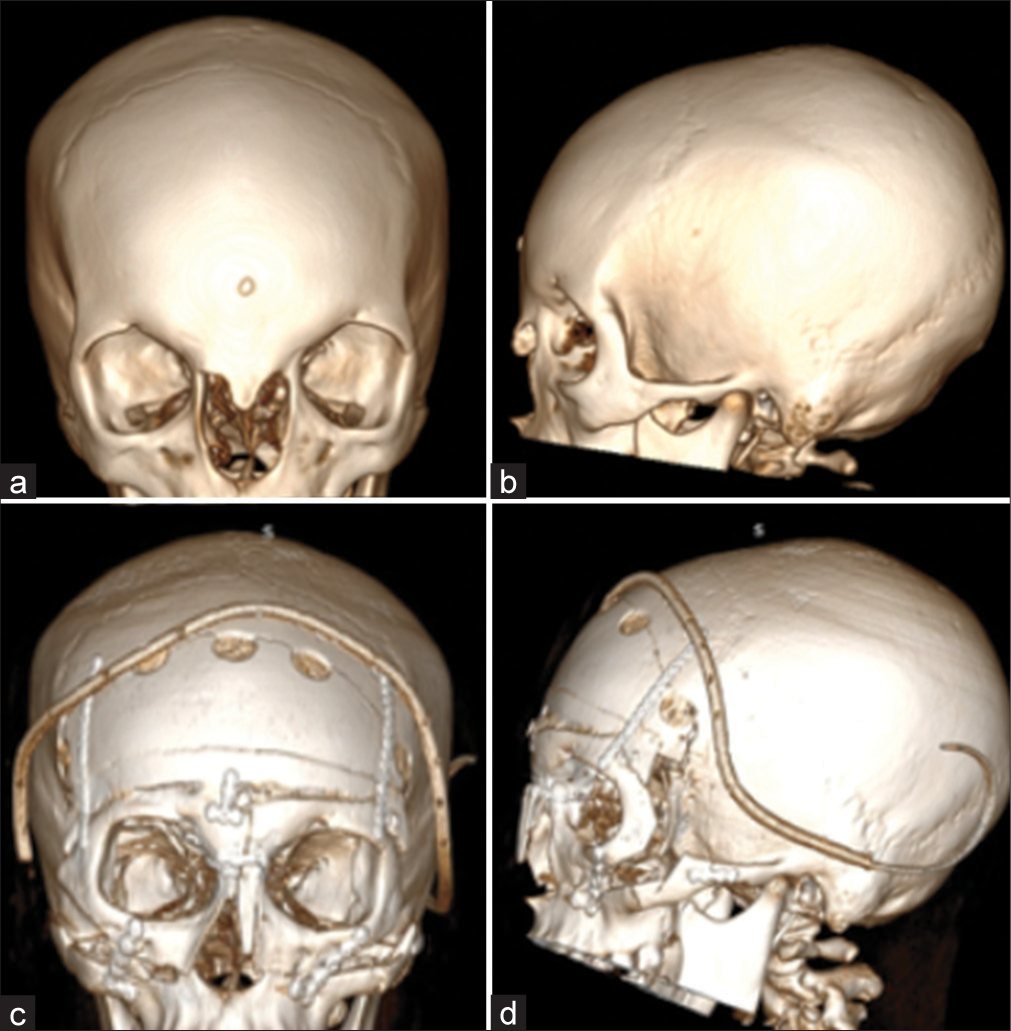

A 13-year-old female [

Case 2

A 15-year-old female [

Operative technique

The box osteotomy was performed in both cases. This technique can be divided into eight steps: (1) patient positioning, airway, and corneal protection; (2) incision and exposure; (3) frontal craniotomy; (4) initial facial osteotomy; (5) final osteotomy and mobilization; (6) skeletal fixation; (7) medial canthal reinforcement and nasal reconstruction; and (8) closure.[

The procedure begins by applying ophthalmic ointment and suturing the upper and lower eyelids horizontally to protect the patient’s cornea. A zigzag-shaped coronal incision is made in the temporal region, followed by a coronal incision on the scalp below the galea. Posteriorly, a subperiosteal dissection is carried out on the supraorbital edges, and the supraorbital nerves are released. The surgeons then make an incision into the zygomatic bone and maxillary buccal, which extends from the medial side of the first molar to the contralateral side. The periorbita is released circumferentially along the roof to 1 cm anterior to the optic nerve superiorly, laterally, medially, and the lateral one-third of the floor, exposing the bilateral zygoma, the arches, the superior orbital rims, the superior surface of the nasal dorsum, the medial wall of the orbit, and the lateral third of the infraorbital rim.[

Once the necessary incisions are made and structures exposed, the neurosurgeons perform a frontal craniotomy by creating burr holes in the pterional and upper frontal regions [

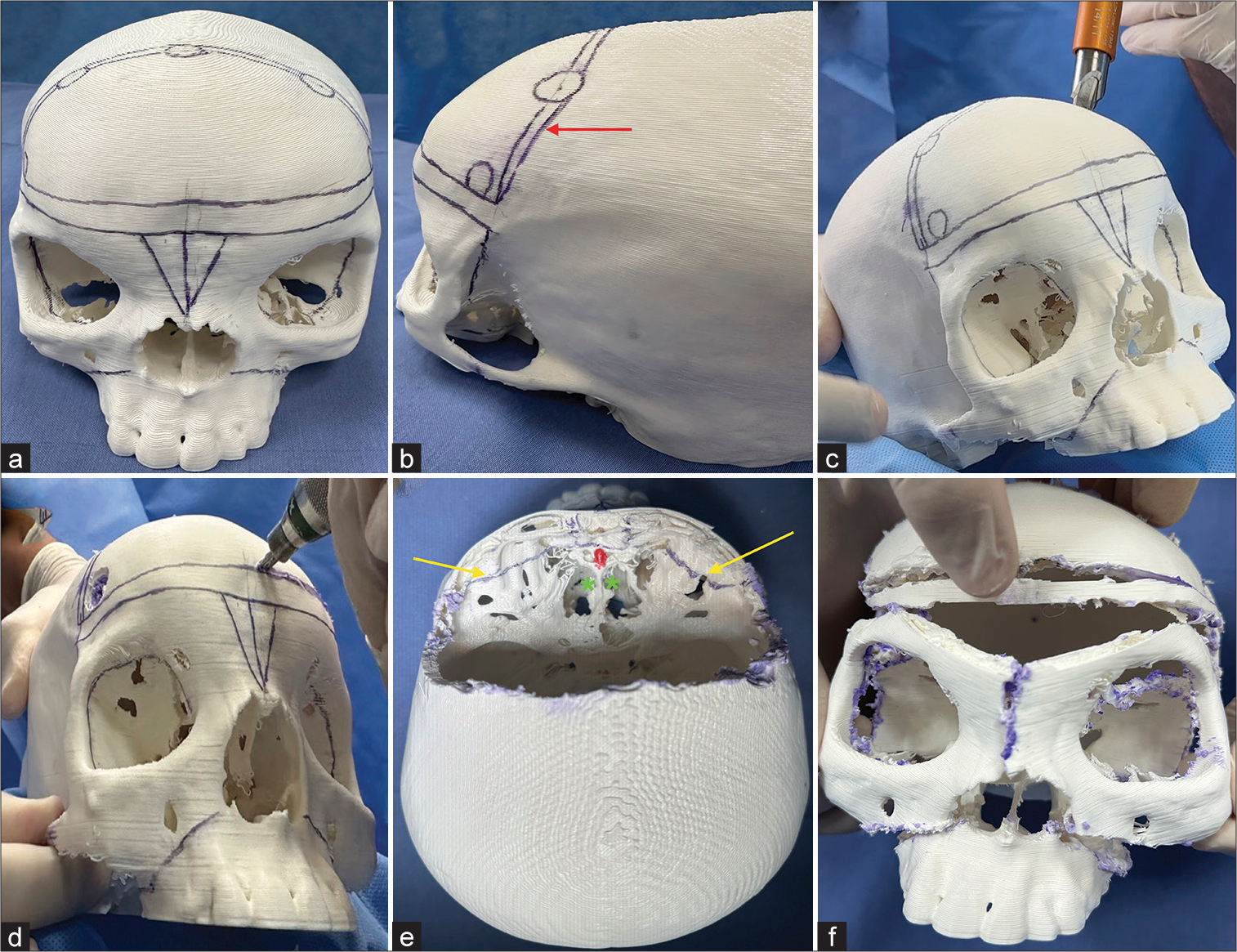

Figure 7:

(a-f) The box osteotomy technique was performed on a 3D printer model – polylactic acid. A high-quality computed tomography scan of patient 1 was used as a model. (a) The 3D skull was painted with a dermatological surgical pencil. The frontal craniotomy and a frontal bandeau of 1 cm were maintained between the frontal bone flap and the orbital osteotomies. A V-shaped osteotomy was performed in the midline. The shape and symmetry vary depending on the desired orbital translocation. (b) Craniotomy burr holes were made in the pterional and upper frontal regions. The red arrow represents the trajectory of the craniotomy. (c) Using a special drill, the neurosurgeon drilled holes in the skull to expose the dura. It is important to protect the superior sagittal sinus in the midline. (d) The craniotome connected each burr hole. (e) The frontal bone flap and bandeau were removed, providing access to the orbital roof, greater wing of sphenoids laterally, and medially cribriform plates. Gentle brain retraction was necessary to avoid injury to the crista galli (red color) and cribriform plate (green asterisk) and preserve olfactory function. Yellow arrows demonstrate orbital roofs and midline osteotomies. (f) Final appearance after the box osteotomy technique, showing that both orbits were adequately translocated.

A V-shaped osteotomy is made in the midline, extending anterior to the crista galli. Depending on the desired translocation of the orbit, its shape and symmetry may vary. To move the orbits closer to each other, the frontal bone, ethmoids, midline nasal dorsum, and superior part of the bony septum are removed. The mobilization of the orbit consists of medial translocation and superior rotation of the lateral orbital rims, allowing hypertelorism correction. Fixation is done using titanium plates and screws. Since the surgery can result in excess skin, it is commonly necessary to remove some skin along with bone resection.[

In the past, some bone structures, such as the ethmoidal labyrinth, nasal bones, and cribriform plate, were removed during box osteotomy. However, it was discovered that this step generally impairs olfactory function due to the anatomical association between the olfactory nerve and the cribriform plate. As a result, it is no longer recommended.[

DISCUSSION

Embryology and physiopathology

The development of the axial skeleton occurs at the end of the 4th week by osteogenesis. The cranium ossification is divided into intramembranous and endochondral bone formation, whose common pathway is the mesenchymal cells.[

There is no common physiopathological pathway that explains its occurrence.[

Group classifications

Patients with hypertelorism can be classified by age group or orbital bone measurements. The first classification is divided into early (from 0 to 7 years old) and late (8 years old or older). It is used to determine the influence of age on surgical results. The ideal age for operating is widely discussed in the literature and differs between some authors. Marchac et al.[

We consider that the best period for surgical correction is before the age of 8. The early correction can improve or prevent the progression of serious neurological disorders (e.g., amblyopia) and promote better esthetic and psychological outcomes. However, some patients cannot be evaluated in the correct period, and early surgery is not an option. This occurs for several reasons, such as parental knowledge, demographic barriers, and administrative problems in public health (e.g., lack of reference centers/professionals resulting in long wait times for appointments). For them, late surgery can be a reasonable option with good results.

The second classification includes the ICD, measured between the anterior lacrimal crests. It can be classified as mild (30 mm < bony interorbital distance ≤34 mm), moderate (34 mm < bony interorbital distance ≤40 mm), and severe (bony interorbital distance >40 mm).[

Surgical techniques and complications

There are several techniques described in the literature: orbital box osteotomy, monobloc frontofacial advancement by distraction, frontofacial bipartition advancement by distraction, and facial bipartition.[

Some authors[

The postoperative complications include infections, CSF leakage, hyposmia or anosmia, oculomotor disorders, epiphora, enophthalmos, obstruction of nasal passages,[

Some soft-tissue deformities are generally expected after correction of hypertelorism, such as bifid nose, eyelid ptosis, epicanthal fold, deviated septum, and excess skin in the midline, which can be corrected later by additional surgeries.[

CONCLUSION

Isolated hypertelorism is a genetic condition that must be corrected to avoid neurological deficits and psychological disturbance. Although some authors suggest better surgical results before 8 years old, our present study describes two late corrections with good outcomes.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and Center of High Complexity Neurosurgery Intern Patients (NIPNAC).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Britto JA, Greig A, Abela C, Hearst D, Dunaway DJ, Evans RD. Frontofacial surgery in children and adolescents: Techniques, indications, outcomes. Semin Plast Surg. 2014. 28: 121-9

2. Cohen MM, Richieri-Costa A, Guion-Almeida ML, Saavedra D. Hypertelorism: Interorbital growth, measurements, and pathogenetic considerations. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995. 24: 387-95

3. Di Ieva A, Bruner E, Haider T, Rodella LF, Lee JM, Cusimano MD. Skull base embryology: A multidisciplinary review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014. 30: 991-1000

4. Ferreira Junior TA, Fontoura RR, Marques do Nascimento L, Alcântara MT, Capuchinho-Júnior GA, Alonso N. Frontofacial monobloc advancement with internal distraction: Surgical technique and osteotomy guide. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2022. 23: e33-41

5. Greig AV, Britto JA, Abela C, Witherow H, Richards R, Evans RD. Correcting the typical Apert face: Combining bipartition with monobloc distraction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013. 131: 219.e-30

6. Greig DM. Hypertelorism: A Hitherto undifferentiated congenital cranio-facial deformity. Edinb Med J. 1924. 31: 560-93

7. Kademani D, Tiwana P, editors. Atlas of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. p. 487-97

8. Laure B, Batut C, Benouhagrem A, Joly A, Travers N, Listrat A. Addressing hypertelorism: Indications and techniques. Neurochirurgie. 2019. 65: 286-94

9. Marchac D, Sati S, Renier D, Deschamps-Braly J, Marchac A. Hypertelorism correction: What happens with growth? Evaluation of a series of 95 surgical cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012. 129: 713-27

10. McCarthy J, editors. Formal problems in Semitic phonology and morphology. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1979. p.

11. Medixa. RadiAnt DICOM viewer. 2021. p. Version 2021. Available from: https://www.radiantviewer.com [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 21]

12. Moore KL, Persaud TV, Torchia MG, editors. The developing human clinically oriented embryology. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2015. p.

13. Patel SY, Ghali GE. Orbital hypertelorism. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2022. 30: 101-12

14. Raposo-Amaral CE, Resende G, Denadai R, Ghizoni E, Raposo-Amaral CA. Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: Hypertelorism correction in late presenting patients. Childs Nerv Syst. 2021. 37: 2873-8

15. Roth DM, Bayona F, Baddam P, Graf D. Craniofacial development: Neural crest in molecular embryology. Head Neck Pathol. 2021. 15: 1-15

16. Setiawati R, Rahardjo P, editors. Bone development and growth. Osteogenesis and bone regeneration. London: IntechOpen; 2019. p.

17. Sharma RK. Hypertelorism. Indian J Plast Surg. 2014. 47: 284-92

18. Sirkek B, Sood G, editors. Hypertelorism. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. p. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560705 [Last accessed on 2023 Jul 24]

19. Tessier P. Experiences in the treatment of orbital hypertelorism. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974. 53: 1-18