- Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

- Department of Neurosurgery, King Saud Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- College of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

- Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

- Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence Address:

Ghadi Ali Shamakhi, College of Medicine, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_60_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Sami Fadhel Almalki1, Abdulelah Saleh Almousa1, Rawan Ahmed Alturki2, Ghadi Ali Shamakhi3, Fatimah Ahmed Alghirash4, Turki Fahhad Almutairi5. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the working hours of parents and caregivers in Saudi Arabia: A survey study. 04-Oct-2024;15:358

How to cite this URL: Sami Fadhel Almalki1, Abdulelah Saleh Almousa1, Rawan Ahmed Alturki2, Ghadi Ali Shamakhi3, Fatimah Ahmed Alghirash4, Turki Fahhad Almutairi5. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the working hours of parents and caregivers in Saudi Arabia: A survey study. 04-Oct-2024;15:358. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13134

Abstract

Background: Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a common result of external physical forces that damage the brain, affecting over 50 million people annually, with a higher prevalence in males. Children aged 0–4 years are the most susceptible, particularly in low-and middle-income countries, where 90% of TBI-related deaths occur. TBI significantly affects children’s quality of life. This study aimed to estimate the incidence of pediatric TBI during working hours among parents and caregivers in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: A questionnaire-based cross-sectional survey was conducted over 2 months, from July to August 2023. The survey data were electronically gathered using a questionnaire sent over social media channels. It includes working as a caregiver for children in Saudi Arabia.

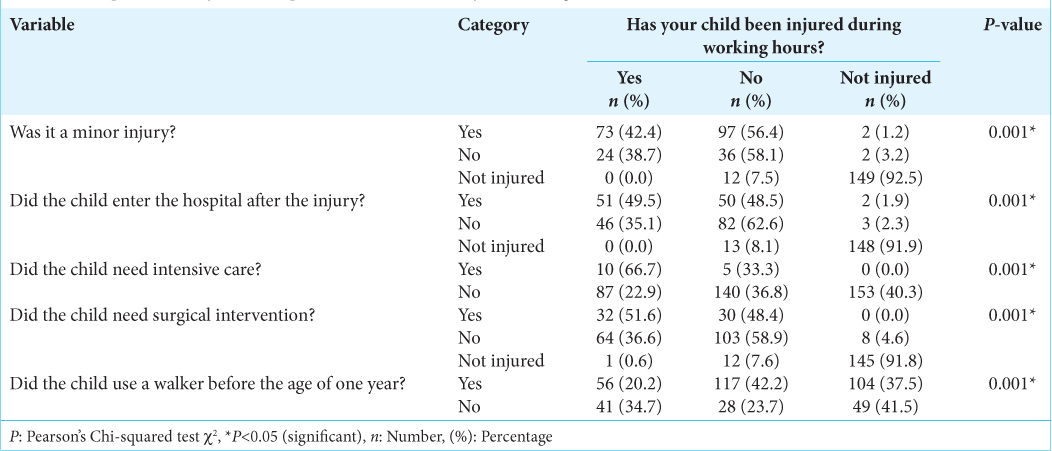

Results: Involving 395 respondents, the primary focus was on child head injuries occurring during the working hours of parents and caregivers. Most respondents were in the 36–45 age bracket, predominantly female (66.1%) and married (81.8%). The age of the child at the time of injury was significantly associated with head injuries during parents’ and caregivers’ working hours, with the highest incidence among children aged 7–14 years (83.1%). The severity of the injury, hospital admission, need for intensive care, and surgical intervention were significantly associated with child injuries during these hours.

Conclusion: In this study, we found a significantly higher incidence of head injuries in children during the working hours of both parents and caregivers. Factors such as longer work hours, the presence of a nanny, more children, male gender, and older child age were associated with this risk.

Keywords: Head trauma, Impact injuries, Non-incidental head trauma, Pediatric trauma cross-sectional study, Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as any external physical force that causes brain damage and impairs its function.[

TBI is one of the most common complaints encountered in neurological surgery worldwide, affecting more than 50 million individuals annually, with males being the most affected.[

In the pediatric population, around 280/100,000 children are affected by TBI every year.[

The severity of TBI has been classified using the Glasgow coma scale (GCS) into mild (GCS ranging from 13 to 15), moderate (GCS ranging from 9 to 12), and severe (GCS ranging from 3 to 8).[

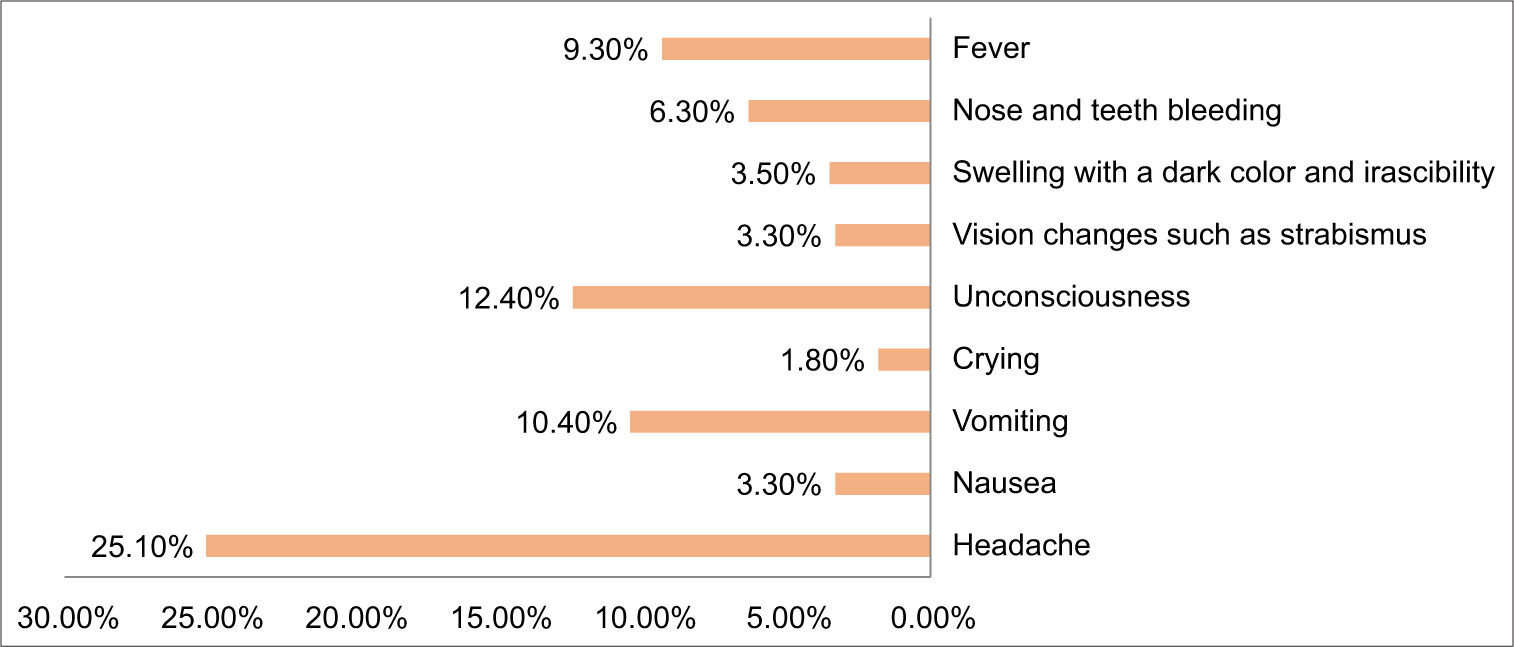

Irritability, headache, nausea, emesis, and diplopia are some of the symptoms of TBI in pediatric patients.[

The frequent causes of pediatric TBI differ with age. Falls are a major cause of TBI in children under the age of 14 years. Those under the age of 4 years are primarily affected by falls, but abusive traumas and motor vehicle accidents sometimes impact them.[

TBI affects pediatrics’ quality of life and has further been linked to a deficiency of neuropsychological and cognitive function, social competence, and school performance.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and study settings

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Saudi Arabia by distributing online questionnaires.

Study population

The study population consisted of children aged 0–14 years in Saudi Arabia.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All male and female pediatric participants aged 0–14 years whose parents worked in Saudi Arabia were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were excluded in the study:

Any questionnaire with an unanswered question(s) Any respondent who was not a parent Any parent who did not work Any respondent who did not live in Saudi Arabia Patients older than 14.

Sampling method and sample size

The sample included Saudi pediatric participants aged – 0–14 years. The sample size was 395, determined using the Richard Geiger equation with a 5% margin of error and 95% confidence level for a population of approximately 8,685,448. Respondents were recruited randomly by disseminating the electronic questionnaire through popular social media channels and parenting groups in Saudi Arabia, including Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Telegram groups. The survey was shared widely to reach working parents from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds across the different regions of Saudi Arabia. However, given the recruitment through social media channels, the sample likely underrepresented families with limited internet access or low social media usage. Information was collected randomly using an electronic questionnaire administered to working parents. The participants provided informed consent. While efforts were made for broad recruitment, the use of social media platforms introduced some selection bias toward users of these platforms. The demographic breakdown of the respondents suggests reasonable representation across age groups, income levels, education levels, and regions within Saudi Arabia.

Data collection tools and processes

Data were collected through an electronic questionnaire (Google Forms).

Definition of head injury

For this study, a “head injury” was defined as any traumatic injury to the head or brain caused by an external force. These include injuries ranging from mild head trauma, such as concussions, to more severe TBIs. The questionnaire specifically asked respondents if their child had experienced any head injury that fit this definition without restricting only moderate or severe TBIs requiring hospitalization. This allowed the capture of head injuries across the entire severity spectrum.

Data entry and statistical analysis

Survey data were collected electronically using a structured questionnaire administered on social media platforms. Respondents self-reported details regarding sociodemographics, child injuries, symptoms, and other relevant factors. After the survey ended, the raw data were downloaded and compiled into a master database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were cleaned to identify and remove incomplete, duplicate, or erroneous entries. The initial analysis generated frequency distributions and descriptive statistics for all variables to characterize the sample demographics and responses. Cross-tabulations examined associations between child injury rates, sociodemographic factors, work hours, caregiving factors, and injury details. Chi-square significance tests were performed on the cross-tabulations to determine whether the observed relationships were statistically significant in relation to parental working hours at P < 0.05. The incidence of child head injuries was calculated and stratified according to the respondents’ sociodemographic, caregiving factors, and child characteristics. All data computations, tables, and charts were generated directly from raw data using SPSS. The results were compiled, organized, and presented based on the study objectives and analytic plans. All analyses were carefully examined to verify the accuracy and consistent interpretation of the collected survey data relating to pediatric head injuries during parents’ work hours.

Ethical considerations

No personal information was used to prioritize participants’ confidentiality and privacy. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical College at King Faisal University.

RESULTS

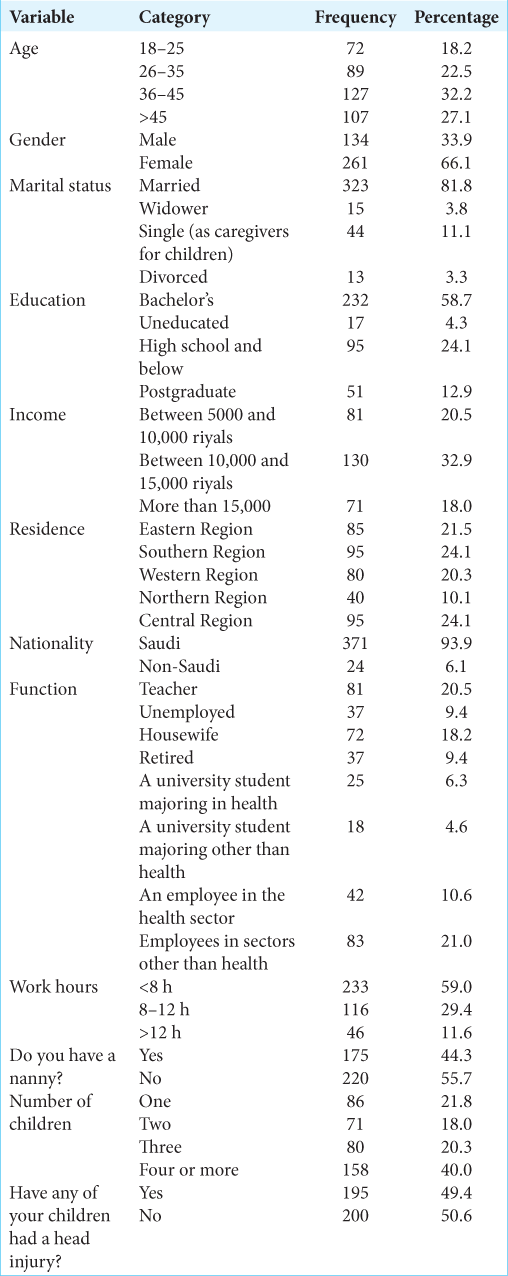

Three hundred and ninety-five respondents completed the study. The sociodemographic factors are shown in

DISCUSSION

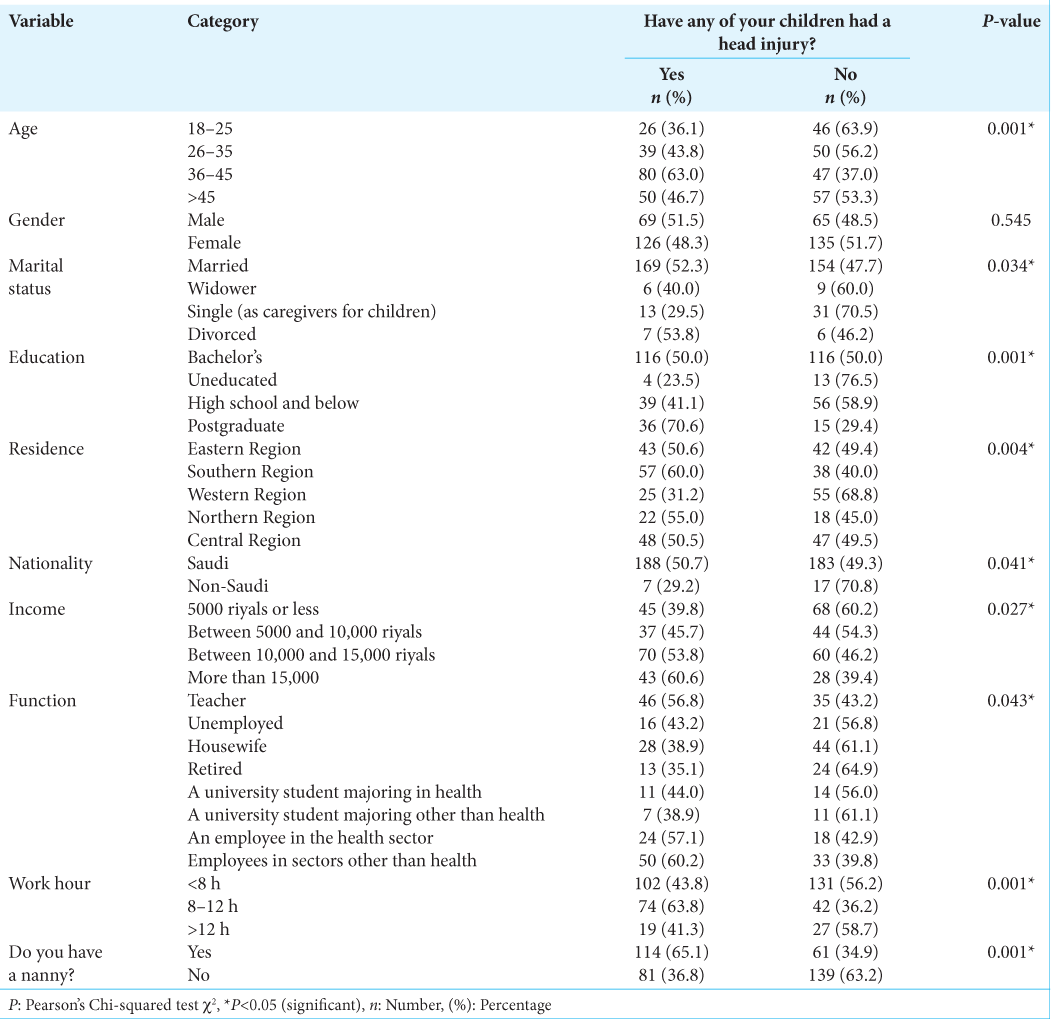

Pediatric TBI is a significant public health concern. This survey was conducted in Saudi Arabia, involving 395 respondents, to explore the relationship between parental working hours and TBI in children. The demographic data from the sample predominantly included individuals aged 36–45 years (32.2%), female parents (66.1%), married (81.8%), and the Southern and Central regions (24.1% each). Several sociodemographic factors, such as age, marital status, education, region, nationality, income, occupation, and parental working hours, were significantly correlated with the incidence of child head injuries (P < 0.05). These findings align with previous studies by McKinlay et al. and Parslow et al., which found similar associations with demographic factors, excluding parental work hours and nanny presence.[

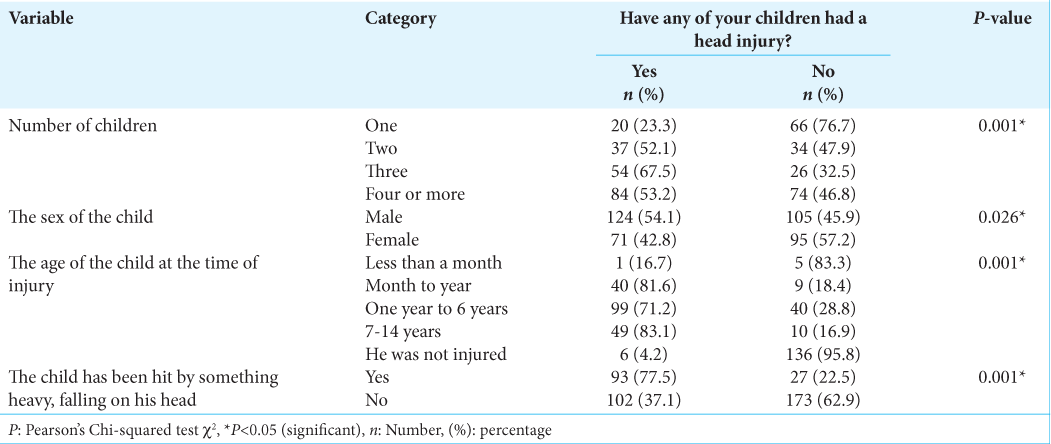

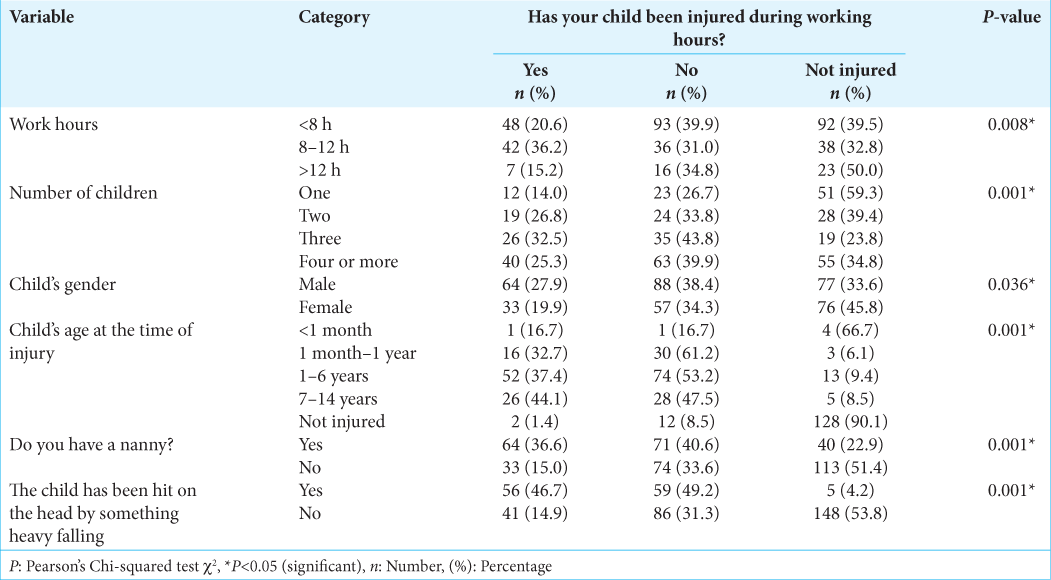

Risk factors such as work hours, nanny availability, and number of children significantly influenced TBI incidence of TBI (P < 0.05). The highest incidence of head injuries (63.8%) was reported by respondents working 8–12 h daily. The presence of a nanny, the number of children, a child being hit by something heavy, a child’s sex, and the child’s age at the time of injury were also significant contributors to the occurrence of TBI (P < 0.05). A study by Alanazi et al. in Saudi Arabia also found a significant correlation with age, with most incidents occurring in children aged 0–12 months (72.6%).[

Several sociodemographic factors, such as region and occupation, also demonstrated significant associations with the incidence of head injuries in children. Respondents from the Southern Region reported the highest incidence (60.0%), followed by those from the northern (55.0%), eastern (50.6%), central (50.5%), and western (31.2%) regions (P = 0.004). Differences may influence these regional variations in urban versus rural environments, accessibility to emergency care, and other socioeconomic and infrastructural disparities across regions.

In terms of occupation, employees in non-health sectors had the highest incidence of child head injuries (60.2%), followed by health sector employees (57.1%) and teachers (56.8%) (P = 0.043). One potential explanation is that parents in certain occupations, such as healthcare, may be more aware of injury risks and prevention strategies. However, the intersection of occupation, work hours, income levels, and other factors requires further investigation to understand specific contributors.

The results of this study provide compelling evidence that children in Saudi Arabia face an increased risk of sustaining head injuries during their parents’ or primary caregivers’ working hours. A significantly higher incidence of pediatric head injuries was reported to occur when children were unsupervised or under non-parental supervision while their parents were at work. Specifically, the data showed that 84.5% of respondents reported that their child suffered a head injury during parental working hours, compared to only 70.3% occurring outside of work hours [

Several factors related to unsupervised time emerged as significant contributors to this elevated risk during work. Longer parental work shifts of 8–12 hours were associated with a 63.8% higher incidence of injuries than shorter shifts [

Possible explanations for this phenomenon include a lack of adequate active supervision, inattentiveness of caregivers juggling other tasks, unfamiliarity with children’s behavior patterns, or even a lack of child-proofing in environments such as households when parents are away. In addition, the higher incidence associated with having a nanny (65.1%) suggests that improper training or a lack of experience in providing childcare may be a contributing factor. This highlights the importance of ensuring that nannies and non-parental caregivers receive appropriate education and guidance regarding child safety measures. One hypothesis for why having a nanny was associated with increased pediatric TBI risk could be related to nannies being unfamiliar with the specific needs, behavioral patterns, and vulnerability of each child compared to parents. Even experienced nannies may not possess the same level of vigilance and attentiveness as parents for their children. Furthermore, there may be a lack of standardized training requirements for nannies in Saudi Arabia regarding childhood safety and injury prevention. Without such formalized training, nannies may be unaware of optimal precautions for minimizing head injury risk during childcare duties. Parental supervision likely also plays a role, as working parents may not consistently reinforce safety guidelines with nannies.

Therefore, improving access to childcare training programs focused on injury prevention could help mitigate the risks of having a nanny. Increasing parental awareness of diligently communicating safety protocols to nannies may also lower pediatric TBI rates.

Child injuries during work hours led to complications such as the severity of the injury, hospital admission, need for intensive care, surgical intervention, and use of a walker before or after the injury, all of which were significantly associated with child injuries during work hours (P < 0.05). Our findings, in line with past studies, revealed the severity of pediatric TBIs and the need for hospital admission.[

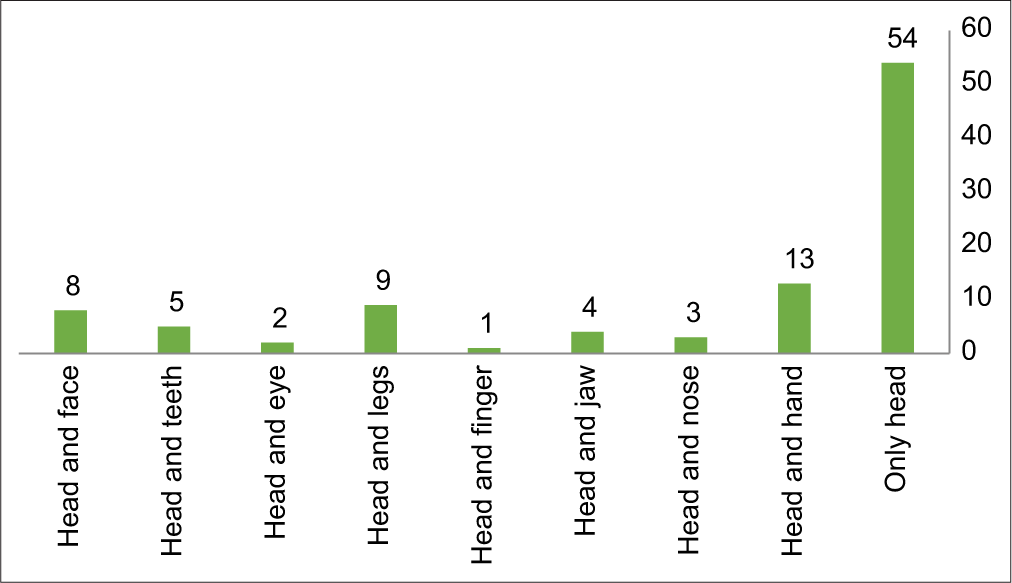

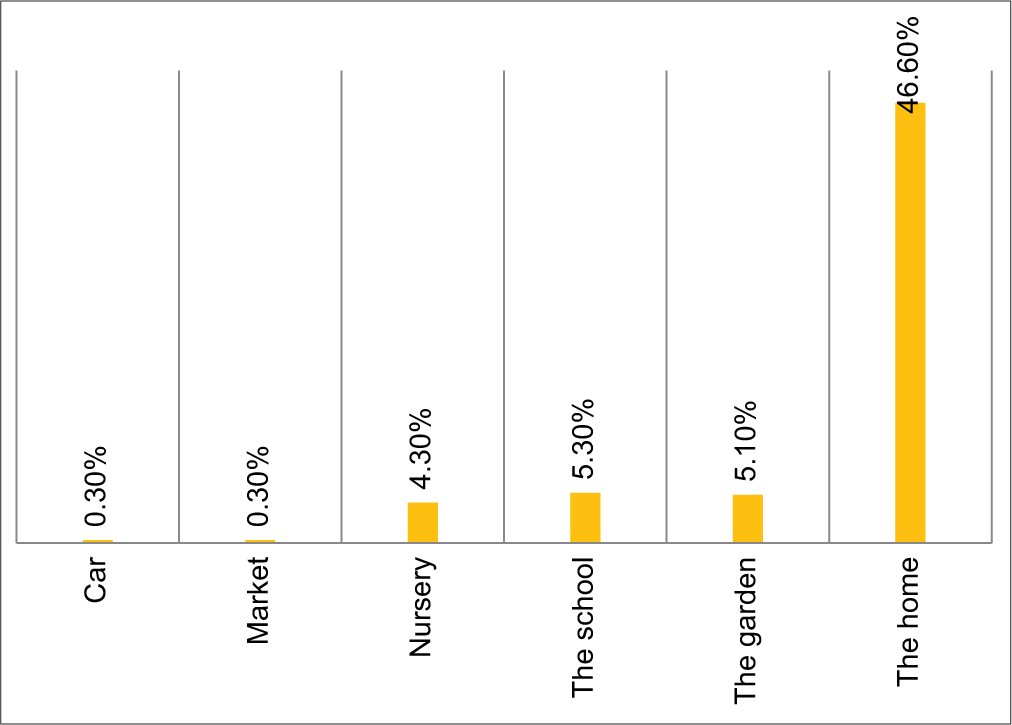

Most injuries were isolated to the head (54 cases), and they typically occurred at home (46.60% of cases), findings consistent with a study by LeBlanc et al.[

The findings emphasize the need to provide safety tools at home, preventive measures, and awareness campaigns targeting parents, particularly those who work long hours and have multiple children. The significant correlation between the incidence of child head injury and having a nanny highlights the importance of training and awareness programs for caregivers and parents in providing a good nanny. These efforts can help reduce the incidence of these injuries among children, promoting a healthier and safer environment.

Study limitations

One limitation is that the study relied on self-reported data, which introduced the possibility of recall bias and potential inaccuracies. Participants may not accurately remember or report specific details about injuries, symptoms, or other relevant information. In addition, due to the study’s cross-sectional design, it is challenging to establish a causal relationship between work hours and the risk of injury. While a survey can identify associations between these variables, it cannot determine causation. Longitudinal analyses would be beneficial for better understanding temporal relationships.

CONCLUSION

This survey study demonstrated a significantly higher incidence of head injuries among children during their parents’ working hours. Several sociodemographic, caregiving, and child-related factors were associated with an increased risk of injury during work hours, including longer work hours, having a nanny, having a higher number of children, a child’s male gender, and an older child’s age. Injuries sustained during parents’ working hours also showed increased severity, with higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care needs, surgery, and specific symptomatology. These findings highlight that inadequate supervision during parents’ working hours is a significant risk factor for pediatric TBI in Saudi Arabia. Implementing more accessible childcare support and flexible work arrangements for parents could mitigate this risk. The results emphasize the need for further research into pediatric injury prevention strategies that account for parental employment obligations.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Faisal University, number KFU-REC-2023-SEP-ETHICS1191, dated September 20, 2023.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgment

We express our deepest gratitude to our supervisor, Dr Sami Fadhel Almaalki. The Faculty of Medicine–Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, King Faisal University, for his support and contributions, which have been invaluable in making this study possible. In addition to the support and contributions of the research team members. Finally, we would like to extend our sincerest appreciation to the study participants and our reviewers for their response and support provided to us.

References

1. Alanazi FS, Saleheen H, Al-Eissa M, Alshamrani AA, Alhuwaymani AA, Jarwan WK. Epidemiology of abusive head trauma among children in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021. 13: e19014

2. Araki T, Yokota H, Morita A. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: Characteristic features, diagnosis, and management. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2017. 57: 82-93

3. Gupte R, Brooks W, Vukas R, Pierce J, Harris J. Sex differences in traumatic brain injury: What we know and what we should know. J Neurotrauma. 2019. 36: 3063-91

4. Hawley CA, Ward AB, Magnay AR, Long J. Parental stress and burden following traumatic brain injury amongst children and adolescents. Brain Inj. 2003. 17: 1-23

5. Haydel MJ, Weisbrod LJ, Saeed W, editors. Pediatric head trauma continuing education activity. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. p.

6. Hymel KP, Makoroff KL, Laskey AL, Conaway MR, Blackman JA. Mechanisms, clinical presentations, injuries, and outcomes from inflicted versus noninflicted head trauma during infancy: results of a prospective, multicentered, comparative study. Pediatrics. 2007. 119: 922-9

7. Kelly KA, Patel PD, Salwi S, Iii HN, Naftel R. Socioeconomic health disparities in pediatric traumatic brain injury on a national level. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2022. 29: 335-41

8. Khanal B, Pokharel K, Shrestha SS, Karn SB, Bhandari N, Shrivastav I. Early outcome of surgery in pediatric head injury: Experience from a tertiary care center in Eastern Nepal. JIOM Nepal. 2020. 42: 16-20

9. Khellaf A, Khan DZ, Helmy A. Recent advances in traumatic brain injury. J Neurol. 2019. 266: 2878-89

10. Kouitcheu R, Diallo M, Mbende A, Pape A, Sugewe E, Varlet G. Traumatic brain injury in children: 18 years of management. Pan Afr Med J. 2020. 37: 235

11. LeBlanc JC, Pless IB, King WJ, Bawden H, Bernard-Bonnin AC, Klassen T. Home safety measures and the risk of unintentional injury among young children: A multicentre case-control study. CMAJ. 2006. 175: 883-7

12. Max JE, Troyer EA, Arif H, Vaida F, Wilde EA, Bigler ED. Traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents: Psychiatric disorders 24 years later. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022. 34: 60-7

13. McKinlay A, Grace RC, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, MacFarlane MR. Long-term behavioural outcomes of pre-school mild traumatic brain injury. Child Care Health Dev. 2010. 36: 22-30

14. Morrongiello BA, Midgett C, Stanton KL. Gender biases in children’s appraisals of injury risk and other children’s risk-taking behaviors. J Exp Child Psychol. 2000. 77: 317-36

15. Ng SY, Lee AY. Traumatic brain injuries: Pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019. 13: 528

16. O’Keefe K, editors. Traumatic brain injury. Emergency medical services: Clinical practice and systems oversight. United States: Wiley; 2015. 1: 237-42

17. Olsen M, Vik A, Lund Nilsen TI, Uleberg O, Moen KG, Fredriksli O. Incidence and mortality of moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in children: A ten year population-based cohort study in Norway. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019. 23: 500-6

18. Park ES, Yang HJ, Park JB. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: The epidemiology in Korea. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2022. 65: 334-41

19. Parslow RC, Morris KP, Tasker RC, Forsyth RJ, Hawley CA. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury in children receiving intensive care in the UK. Arch Dis Child. 2005. 90: 1182-7

20. Schneier AJ, Shields BJ, Hostetler SG, Xiang H, Smith GA. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury and associated hospital resource utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006. 118: 483-92

21. Trimble DJ, Parker SL, Zhu L, Cox CS, Kitagawa RS, Fletcher SA. Outcomes and prognostic factors of pediatric patients with a Glasgow Coma Score of 3 after blunt head trauma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020. 36: 2657-65

22. Wade SL, Kaizar EE, Narad ME, Zang H, Kurowski BG, Miley AE. Behavior problems following childhood TBI: The role of sex, age, and time since injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2020. 35: E393-404

23. Wang Z, Nguonly D, Du RY, Garcia RM, Lam SK. Pediatric traumatic brain injury prehospital guidelines: A systematic review and appraisal. Childs Nerv Syst. 2022. 38: 51-62