- Department of Neurosurgery, Suzuka General Hospital, Suzuka, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Mie University Graduate School of Medicine, Tsu, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Hideki Nakajima, Department of Neurosurgery, Suzuka General Hospital, Suzuka, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_232_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Hideki Nakajima1, Takuro Tsuchiya1, Shigetoshi Shimizu1, Hidenori Suzuki2. A case of traumatic acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma due to injured dural branch of anterior cerebral artery. 12-Aug-2022;13:355

How to cite this URL: Hideki Nakajima1, Takuro Tsuchiya1, Shigetoshi Shimizu1, Hidenori Suzuki2. A case of traumatic acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma due to injured dural branch of anterior cerebral artery. 12-Aug-2022;13:355. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11790/

Abstract

Background: The precise causes of traumatic acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma (AISDH) are unclear in most cases, and there are few cases, where the sources of bleeding are directly confirmed intraoperatively. We report a rare case of traumatic AISDH, in which a damaged dural branch of anterior cerebral artery (ACA) to the cerebral falx was identified as the cause of bleeding during hematoma removal.

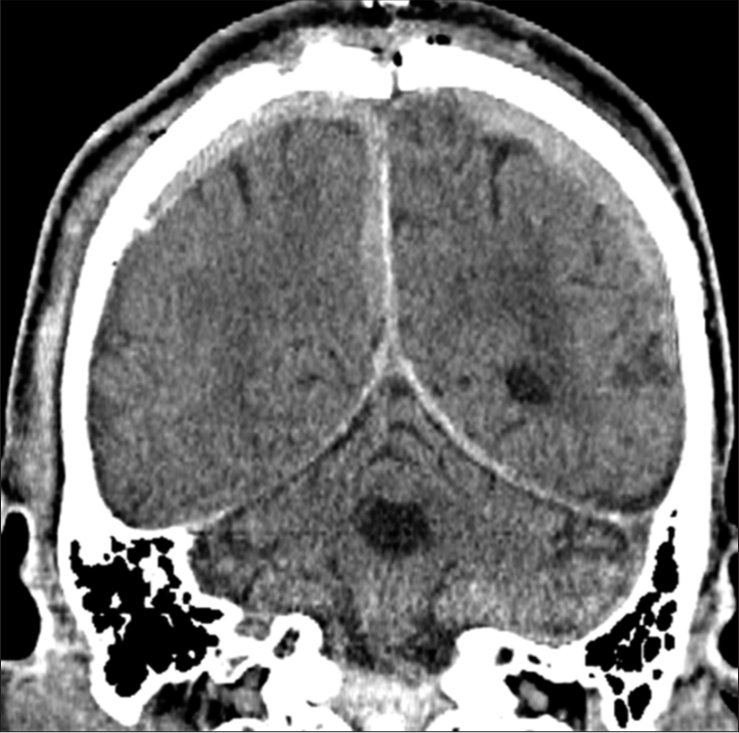

Case Description: A 61-year-old man with a history of craniotomy for the left putaminal hemorrhage at the age of 50 fell from a bed, bruised his head, and lost consciousness. Computed tomography of the head showed AISDH of 2.5cm in thickness, which was removed through a parietal parasagittal craniotomy under the microscope. Intraoperatively, the bleeding source was revealed to be a damaged dural branch from ACA to the cerebral falx. There was no rebleeding during his stay in our hospital.

Conclusion: In this case, intraoperative findings revealed that the cause of bleeding was a damage to the dural branch of ACA. A vascular study is mandatory to rule out a vascular malformation in similar cases.

Keywords: Acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma, Dural arteriovenous fistula, Dural branch of anterior cerebral artery, Falcine sinus, Falx syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma (AISDH) rarely causes neurological deficits, requiring surgery.[

CASE PRESENTATION

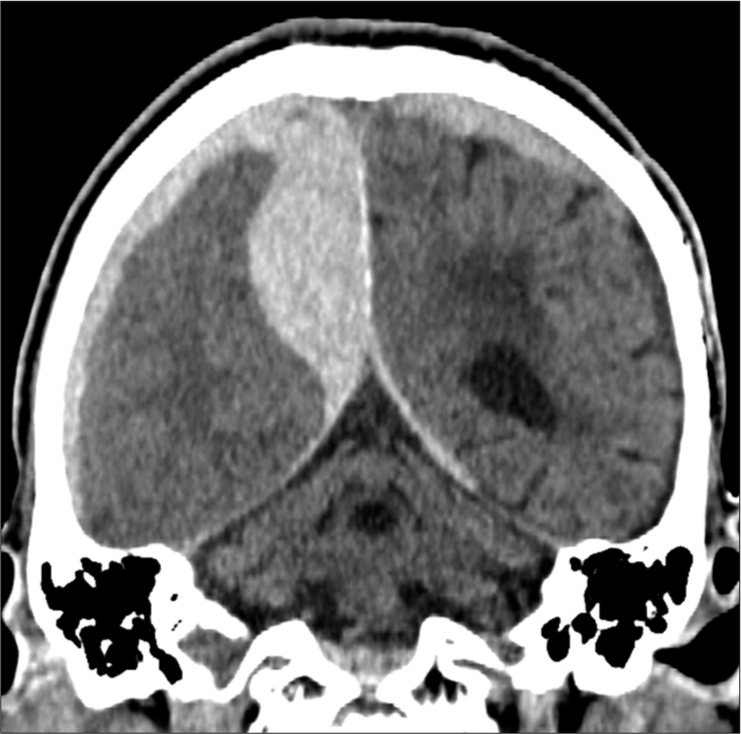

A 61-year-old man fell from a bed in a facility, bruised his head, and lost consciousness, being brought to our hospital. The patient had a history of craniotomy for the left putaminal hemorrhage at the age of 50, which caused permanent motor aphasia and right hemiparesis (manual muscle test [MMT], 2/5). On admission, the patient was comatose associated with the left hemiplegia and was found to have a subcutaneous hematoma and abrasion on his right forehead. He had neither disorders of coagulation nor consumption of alcohol or anticoagulants. Computed tomography (CT) of the head showed AISDH of 2.5 cm in thickness and thin bilateral convexity subdural hematomas [

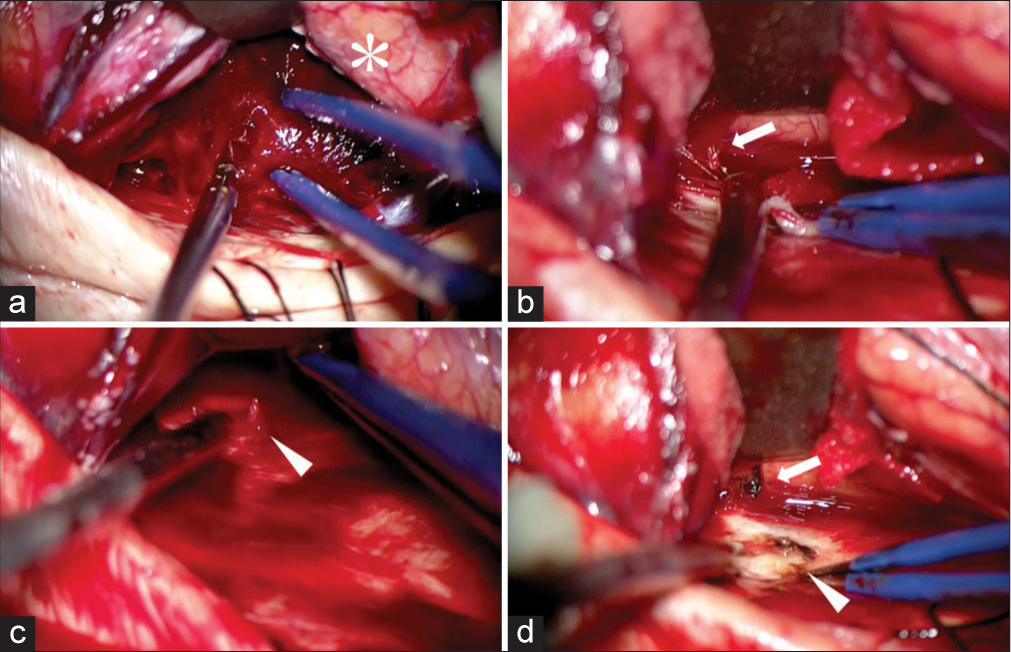

Figure 2:

Intraoperative findings during removal of AISDH. Intraoperative findings show that there is neither brain contusion nor a rupture of the bridging vein (a). *Brain. As the hematoma is removed, arterial bleeding (arrow) is found from a branch of anterior cerebral artery (ACA) (b). The vessel is torn and the other end is found to be continuous with the cerebral falx from which arterial bleeding (arrowhead) is also observed (c). Both ends of the vessel are very close together and are coagulated to stop bleeding (torn ends of the ACA branch: arrow, brain side; arrowhead, falx side) (d).

DISCUSSION

Traumatic AISDH is not a rare condition. Elderly people with enlarged subdural space due to cerebral atrophy, excessive alcohol consumption, anticoagulant medication, and coagulopathy were reported to be risk factors for AISDH.[

While most of cases are asymptomatic and the prognosis is good, AISDH may cause falx syndrome such as contralateral hemiplegia with lower limb dominance, monoplegia of the contralateral lower limb, altered sensorium, gait disturbance, seizure/convulsion, and aphasia.[

As causes of AISDH, an injury to the cortical branch of ACA by cerebral falx, bridging vein injury, and cerebral contusion were reported: however, the source of bleeding was rarely found by surgery or imaging studies, and most were of unknown cause.[

The cerebral falx is fed by the anterior falcine artery, which runs from the end of the anterior ethmoidal artery through the canalis orbitocranialis into the anterior cranial fossa, and then from the cerebral falx attachment at the tip of crista galli through the dura mater of the cerebral falx along the endocranial plate. Although the anterior falcine artery rarely branches off from the ophthalmic artery to the cerebral falx, there are no reports of ACA branching into the cerebral falx, except under special conditions such as the coexistence of dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVFs) and meningiomas. It was reported that physiological arteriovenous shunts in the dura mater might become apparent under the influence of changes in intracranial pressure after surgery, leading to the development of an arteriovenous fistula.[

CONCLUSION

In the present case, intraoperative findings revealed that the cause of bleeding was a damaged dural branch of ACA. It was thought that a dAVF could have been formed after craniotomy or that the patient could have had a falcine sinus dAVF, although no vascular study was performed to identify it. Further, accumulation of similar cases is desirable.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ahn JM, Lee KS, Shim JH, Oh JS, Shim JJ, Yoon SM. Clinical features of interhemispheric subdural hematomas. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2017. 13: 103-7

2. Ahn JY, Kim OJ, Joo YJ, Joo JY. Dural arteriovenous malformation occurring after craniotomy for pial arteriovenous malformation. J Clin Neurosci. 2003. 10: 134-6

3. Cragun BN, Noorbakhsh MR, Hite Philp F, Suydam ER, Ditillo MF, Philp AS. Traumatic parafalcine subdural hematoma: A clinically benign finding. J Surg Res. 2020. 249: 99-103

4. Karibe H, Hayashi T, Hirano T, Kameyama M, Nakagawa A, Tominaga T. Clinical characteristics and problems of traumatic brain injury in the elderly. Jpn J Neurosurg. 2014. 23: 965-72

5. Léveillé E, Schur S, AlAzri A, Couturier C, Maleki M, Marcoux J. Clinical characterization of traumatic acute interhemispheric subdural hematoma. Can J Neurol Sci. 2020. 47: 504-10

6. Nishimoto Y, Takahashi K, Hayashi S, Hasegawa Y, Miyamoto N, Naito I. Two cases of dural arteriovenous fistula that developed after surgery in sites remote from the craniotomy. Jpn J Neurosurg. 2014. 23: 667-71

7. Takeuchi S, Takasato Y, Masaoka H, Hayakawa T, Yatsushige H, Sugawara T. Traumatic interhemispheric subdural haematoma: Study of 35 cases. J Clin Neurosci. 2010. 17: 1527-9

8. Tonetti DA, Ares WJ, Okonkwo DO, Gardner PA. Management and outcomes of isolated interhemispheric subdural hematomas associated with falx syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2019. 131: 1920-5

9. Wang Y, Wang C, Cai S, Dong J, Yang L, Chen L. Surgical management of traumatic interhemispheric subdural hematoma. Turk Neurosurg. 2014. 24: 228-33

10. Yamaguchi T, Higaki A, Yokota H, Mashiko T, Oguro K. A case of dural arteriovenous fistula in the falx cerebri: Case report and review of the literature. NMC Case Rep J. 2016. 3: 67-70

11. Yoshioka S, Moroi J, Kobayashi S, Furuya N, Ishikawa T. A case of falcine sinus dural arteriovenous fistula. Neurosurgery. 2013. 73: E554-6