- Department of Neurological Surgery, School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco,

- Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, Madison,

- Harvard Plastic Residency Program, Harvard Medical School, Boston, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Simon Gashaw Ammanuel, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, Madison, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_502_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Caleb Simpeh Edwards1, Simon Gashaw Ammanuel2, Ogonna N. Nnamani Silva3, Garret P. Greeneway2, Katherine M. Bunch2, Lars W. Meisner2, Paul S. Page2, Azam S. Ahmed2. Academics versus the Internet: Evaluating the readability of patient education materials for cerebrovascular conditions from major academic centers. 02-Sep-2022;13:401

How to cite this URL: Caleb Simpeh Edwards1, Simon Gashaw Ammanuel2, Ogonna N. Nnamani Silva3, Garret P. Greeneway2, Katherine M. Bunch2, Lars W. Meisner2, Paul S. Page2, Azam S. Ahmed2. Academics versus the Internet: Evaluating the readability of patient education materials for cerebrovascular conditions from major academic centers. 02-Sep-2022;13:401. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11841/

Abstract

Background: Health literacy profoundly impacts patient outcomes as patients with decreased health literacy are less likely to understand their illness and adhere to treatment regimens. Patient education materials supplement in-person patient education, especially in cerebrovascular diseases that may require a multidisciplinary care team. This study aims to assess the readability of online patient education materials related to cerebrovascular diseases and to contrast the readability of those materials produced by academic institutions with those of non-academic sources.

Methods: The readability of online patient education materials was analyzed using Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) and Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) assessments. Readability of academic-based online patient education materials was compared to nonacademic online patient education materials. Online patient education materials from 20 academic institutions and five sources from the web were included in the analysis.

Results: Overall median FKGL for neurovascular-related patient online education documents was 11.9 (95% CI: 10.8–13.1), reflecting that they are written at a 12th grade level, while the median FRE was 40.6 (95% CI: 34.1–47.1), indicating a rating as “difficult” to read. When comparing academic-based online patient education materials to other internet sources, there was no significant difference in FRE and FKGL scores (P = 0.63 and P = 0.26 for FKGL and FRE, respectively).

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that online patient education materials pertaining to cerebrovascular diseases from major academic centers and other nonacademic internet sites are difficult to understand and written at levels significantly higher than that recommended by national agencies. Both academic and nonacademic sources reflect this finding equally. Further study and implementation are warranted to investigate how improvements can be made.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular disease, Cerebrovascular surgery, Health literacy, Patient education, Readability

INTRODUCTION

Cerebrovascular neurosurgery is a neurosurgical subspecialty in which many of its disease entities require complex decision-making. Such decision-making aims to balance potential neurological risks with the inherent risk of a surgical or endovascular intervention. This complex decision-making process also involves evaluating the use of multiple treatment modalities and collaboration with multiple providers from different biases and backgrounds. As a result, it can be challenging for patients as they try to navigate medical decisions for themselves, their families, and their loved ones. The increasing incidence of incidentally discovered cerebrovascular disorders only makes these decisions more challenging.[

In response to these challenges, academic neurosurgery departments have created online education materials for patients with the primary objectives of defining diagnoses, describing risk factors, explaining disease natural history, and outlining available treatment options of cerebrovascular conditions. In addition to the description of treatment options, online materials typically aim to discuss anticipated results and potential complications that pertain to cerebrovascular surgery. However, an assessment of the efficacy of how well cerebrovascular-related patient educational materials communicate essential information to patients is lacking.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) recommends that patient education materials are written at a 6th grade level,[

The aim of this study is to analyze the readability of patient education materials pertaining to cerebrovascular conditions. We sought to examine the readability of materials from academic centers and compared these to other more easily available online sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To identify institutions with readily available patient education materials related to cerebrovascular conditions, the listing of academic centers in the US News and World Report was utilized.

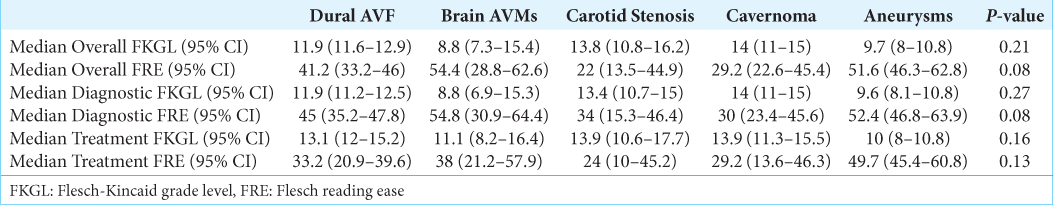

Documents were chosen for study evaluation if they contained content that discussed five common cerebrovascular conditions: Dural arteriovenous fistulas, brain arteriovenous malformations, carotid stenosis, cavernomas, and brain aneurysms. Each academic institution had up to five documents included per topic, while the first five articles from nonacademic sites were analyzed for each topic. A “Diagnosis” subgroup was created using documents relating to epidemiology, symptoms, and diagnosis. A “treatment” subgroup was made with articles connected to treatment, management, and prognosis. Only online content written in English was included in the analysis.

All documents were assessed using plain text with Microsoft Word for Mac version 16.20. The FKGL and FRE for each article were generated. This technique has been previously described by Sabharwal et al.[

Median values and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for FKGL and FRE for each article included. A oneway analysis of variation was calculated across regions and conditions. Two-tailed t-tests were used to compare documents from academic centers to alternate internet information. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad 7 (GraphPad), VassarStats (

RESULTS

Eighteen of 20 included institutions (90%) [

The median FKGL for all documents across all institutions was 11.7 (95% CI: 10.7–12.4), and the median FRE was 42.9 (95% CI: 41.3–46.1). Median FKGL and FRE scores across geographical regions are shown in

The overall median FKGL for all documents from the internet [

DISCUSSION

Cerebrovascular neurosurgery encompasses a number of complex conditions that are often difficult for patients to understand. To further complicate matters, these conditions are frequently managed by multiple providers from numerous specialties, some of which may potentially be located at separate institutions. Often, these providers will have conflicting ideas and offer contrasting advice to patients.[

These common patient experiences do not mean that patient education efforts are doomed to fail. For example, an in-depth educational and interactive informed consent process involving booklets, cartoons, videos, questionnaires, and interviews was found to significantly increase comprehension in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms as compared to controls.[

In our study, we found that online patient education materials pertaining to cerebrovascular disease provided by academic medical centers were often challenging to read and properly understand. Difficulties in readability and comprehension were also observed when comparing the readability of cerebrovascular neurosurgical information provided by medical centers to those found on other sites. These challenges are suggestive that, in aggregate, medical information is written at too high of a reading level. To add, our data suggest that this is not a problem limited to tertiary and academic medical institutions. A similar, though more limited, investigation into the readability of online reading materials for brain aneurysms also came to the conclusion that patient education materials are written at levels too high for patients to understand.[

The American Medical Association and National Institutes of Health have recommended that patient education materials be written at the 6th-grade level or below.[

It is clear that there is a need for more readable patient education materials to improve health literacy, which has already resulted in improvements in literacy within other medical specialties.[

This study is inherently limited in scope. The FKGL and FRE tests are unable to account for accompanying images and videos found online. Additional differences in presentation and layout that may affect a patient’s reading experience and understanding could not be considered. Furthermore, we are unable to comment on how the readability of these documents is affected by translations into other languages or for websites written in other languages. Language discordance is an important factor in promoting health literacy and has been associated with increased risk of readmission, longer length of stay, and even infection rates.[

CONCLUSION

Cerebrovascular conditions can be challenging for patients to understand and often require input by physicians from multiple subspecialties, presenting patients with different perspectives on risk and conflicting advice for treatment. Patient education materials provide an essential adjunct to in-person patient education during a consultation and can make all the information they are presented with more easily comprehended. However, our study indicates that currently available information from major U.S. academic centers and other nonacademic websites pertaining to cerebrovascular disease are written at a level significantly higher than recommended by national agencies. The authors of these articles should factor the NIH and AMA guidelines of patient education materials to allow patients to make informed health-care decisions. The future studies should focus on improving the readability of the articles to understand the effects of patient outcomes related to these diseases.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Abbott SA. The benefits of patient education. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1998. 21: 207-9

2. Ammanuel SG, Edwards CS, Alhadi R, Hervey-Jumper SL. Readability of online neuro-oncology-related patient education materials from tertiary-care academic centers. World Neurosurg. 2020. 134: e1108-14

3. Bailey SC, O’Conor R, Bojarski EA, Mullen R, Patzer RE, Vicencio D. Literacy disparities in patient access and health-related use of Internet and mobile technologies. Health Expect. 2015. 18: 3079-87

4. Bartels U, Hargrave D, Lau L, Esquembre C, Humpl T, Bouffet E. Analysis of paediatric neuro-oncological information on the Internet in German language. Klin Padiatr. 2003. 215: 352-7

5. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011. 155: 97-107

6. Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004. 19: 1228-39

7. Ducroux C, Fahed R, Khoury NN, Gevry G, Kalsoum E, Labeyrie MA. Intravenous thrombolysis and thrombectomy decisions in acute ischemic stroke: An interrater and intrarater agreement study. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2019. 175: 380-9

8. Ellis JA, Barrow DL. Supratentorial cavernous malformations. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017. 143: 283-9

9. Eltorai AE, Cheatham M, Naqvi SS, Marthi S, Dang V, Palumbo MA. Is the readability of spine-related patient education material improving? An assessment of subspecialty websites. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016. 41: 1041-8

10. Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948. 32: 221-33

11. Gupta R, Adeeb N, Griessenauer CJ, Moore JM, Patel AS, Kim C. Evaluating the complexity of online patient education materials about brain aneurysms published by major academic institutions. J Neurosurg. 2017. 127: 278-83

12. John-Baptiste A, Naglie G, Tomlinson G, Alibhai SM, Etchells E, Cheung A. The effect of English language proficiency on length of stay and in-hospital mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2004. 19: 221-8

13. Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, Auerbach AD. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. J Hosp Med. 2010. 5: 276-82

14. Kim PS, Choi CH, Han IH, Lee JH, Choi HJ, Lee JI. Obtaining informed consent using patient specific 3D printing cerebral aneurysm model. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2019. 62: 398-404

15. Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS.editors. Derivation of New Readability Formulas Personnel Flesch Reading Ease Formula) For Navy Enlisted Personnel. Research Branch Report. 1975. p. 8-75

16. King JT, Yonas H, Horowitz MB, Kassam AB, Roberts MS. A failure to communicate: Patients with cerebral aneurysms and vascular neurosurgeons. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005. 76: 550-4

17. Lunsford LD, Niranjan A, Kano H, Monaco EA, Flickinger JC. Leksell stereotactic radiosurgery for cavernous malformations. Prog Neurol Surg. 2019. 34: 260-6

18. Mooney MA, Zabramski JM. Developmental venous anomalies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017. 143: 279-82

19. 20. Nguyen MH, Smets EM, Bol N, Bronner MB, Tytgat KM, Loos EF. Fear and forget: How anxiety impacts information recall in newly diagnosed cancer patients visiting a fast-track clinic. Acta Oncol. 2019. 58: 182-8 21. Park J, Son W, Park KS, Kang DH, Lee J, Oh CW. Educational and interactive informed consent process for treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2017. 126: 825-30 22. Ramos CL, Williams JE, Bababekov YJ, Chang DC, Carter BS, Jones PS. Assessing the understandability and actionability of online neurosurgical patient education materials. World Neurosurg. 2019. 130: e588-97 23. Roberts H, Zhang D, Dyer GS. The readability of AAOS patient education materials: Evaluating the progress since 2008. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016. 98: e70 24. Sabharwal S, Badarudeen S, Unes Kunju S. Readability of online patient education materials from the AAOS web site. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008. 466: 1245-50 25. Schoof ML, Wallace LS. Methods Materials and Procedures Readability of American Academy of Family Physicians Patient Education Materials Assessment of Reading Demands. Brief Report. 2014. 46: 26. Stenberg U, Vågan A, Flink M, Lynggaard V, Fredriksen K, Westermann KF. Health economic evaluations of patient education interventions a scoping review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2018. 101: 1006-35 27. Tang EW, Go J, Kwok A, Leung B, Lauck S, Wong ST. The relationship between language proficiency and surgical length of stay following cardiac bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016. 15: 438-46 28. Walsh TM, Volsko TA. Readability assessment of internet-based consumer health information. Respir Care. 2008. 53: 1310-5 29. Weiss BD.editors. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2003. p. 30. Zipfel GJ, Derdeyn CP, Dacey RG. Current status of manpower needs for management of cerebrovascular disease. Neurosurgery. 2006. 59: S261-70