- Hand and Microsurgery Center, Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Nangang, Harbin, China

- State-Province Key Laboratories of Biomedicine-Pharmaceutics, Harbin Medical University, Nangang, Harbin, China

- Heilongjiang Medical Science Institute, Harbin Medical University, Nangang, Harbin, China

- Department of Stem Cell Biology, School of Medicine, Konkuk University, Seoul, Korea

- HEAVEN-GEMINI International Collaborative Group, Turin, Italy

DOI:10.25259/SNI-19-2019

Copyright: © 2019 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Xiaoping Ren, C-Yoon Kim, Sergio Canavero. Bridging the gap: Spinal cord fusion as a treatment of chronic spinal cord injury. 26-Mar-2019;10:51

How to cite this URL: Xiaoping Ren, C-Yoon Kim, Sergio Canavero. Bridging the gap: Spinal cord fusion as a treatment of chronic spinal cord injury. 26-Mar-2019;10:51. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9232/

Abstract

Despite decades of animal experimentation, human translation with cell grafts, conduits, and other strategies has failed to cure patients with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI). Recent data show that motor deficits due to spinal cord transection in animal models can be reversed by local application of fusogens, such as Polyethylene glycol (PEG). Results proved superior at short term over all other treatments deployed in animal studies, opening the way to human trials. In particular, removal of the injured spinal cord segment followed by PEG fusion of the two ends along with vertebral osteotomy to shorten the spine holds the promise for a cure in many cases.

Keywords: Electrical stimulation, GEMINI, polyethylene glycol, spinal cord fusion, spinal cord transection

To L. Walter Freeman, in memoriam

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana

TREATMENT OF SPINAL PARALYSIS: STATE-OF-THE-ART

Spinal cord injury (SCI) in man often leads to severe permanent disability. Ever since the work of Ramon and Cajal,[

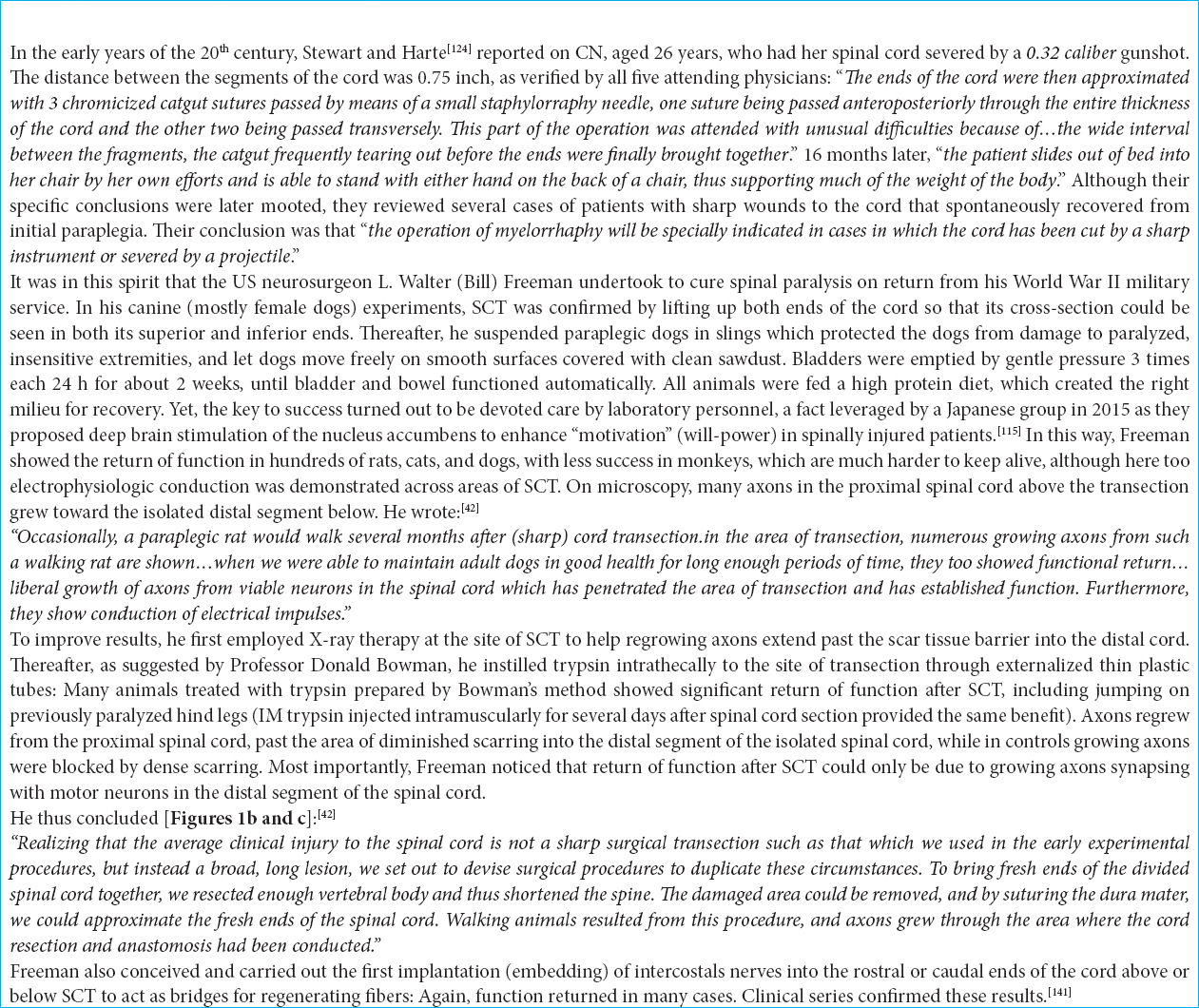

Several therapeutic strategies have been deployed over the past 40 years in experimental animals, with a focus on cell grafts, particularly grafts of various types of stem cells, into the injury site, to form a neuronal relay circuit across the gap.[

Spurred by promising animal studies, clinical trials of a wide variety of different cell lines implanted at or around the lesional level (Schwann cells – SC, olfactory ensheathing glia – OEG - residing either in the lamina propria or along the nerve fiber layer of the olfactory bulb, mesenchymal/stromal stem cells – MSC, some of which may acquire neuronal properties, multipotent progenitor cells – MPC, neural stem/progenitor cells – NSC, embryonic stem cells – ECS, and umbilical cord blood cells) have been (and are being) conducted over the past 20 years.[

In sum, while some benefit may accrue from cell grafts and other techniques, they alone cannot cure paralysis.[

In this paper, we will review the evidence supporting an idea posited half a century ago by the US neurosurgeon L. Walter Freeman, namely that a permanent, biological cure is possible in several cases, by cutting out the most damaged portion of the spinal cord and connecting the two free ends, after spinal shortening [

SPINAL CORD TRANSECTION: NATURAL HISTORY

In man, no recovery follows spinal cord transection (SCT) at whatever level as seen, for example, after stab wounds.[

A similar assessment applies to experimental animals. Handa et al.[

Rodents follow a similar pattern. In untreated mice with dorsal SCT, 33% displayed weak nonbilaterally alternating movements (NBA) at 1 week. At 2 weeks, increased NBA were observed and the first BA movements in 10% of the animals. A progressive increase of movement frequency and amplitude was found after 2–3 weeks. By the end of the month, 86% displayed mixed NBA and BA. However, none of them recovered the ability to stand or bear their own weight with the hindlimbs.[

SPINAL CORD TRANSECTION: EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENT IN ANIMALS

It is clear from the above section that SCT lends itself as the ideal model to study neuroregenerative strategies. However, marked differences exist between human and rodent spinal cords both in anatomy and secondary injury processes,[

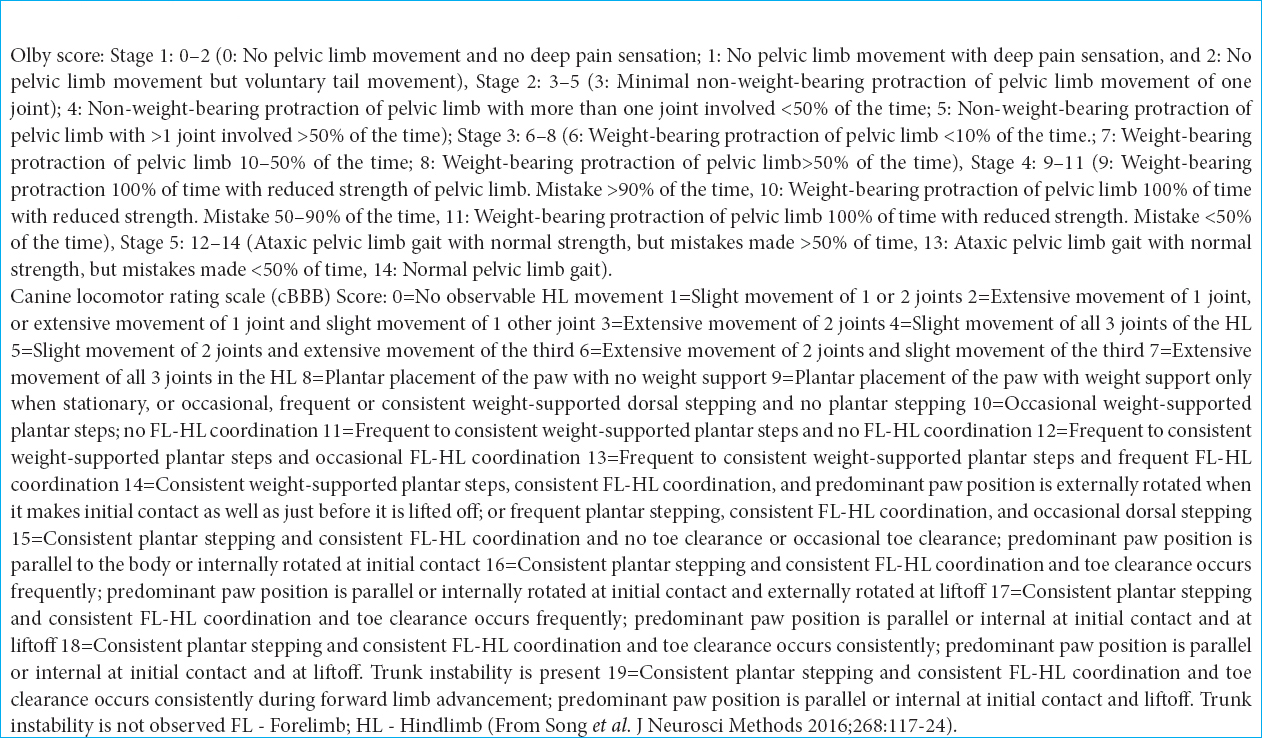

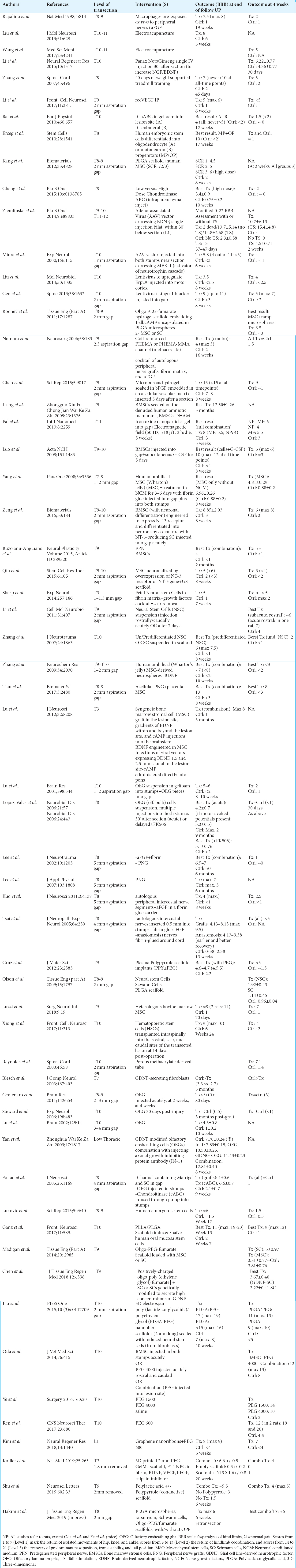

As can be seen from

In the few canine studies, PEG fusion is again superior [

Even in monkeys, cell grafts are not especially promising, despite claims to the contrary in some papers. For instance, a grafting study of human fetal spinal cord-derived neural progenitor cells after C7 hemisection reported a >25% improvement in object manipulation scores in four of five monkeys (vs. 1 out of 4 controls that improved so) and a 12% improvement in climbing score, beginning several months after grafting.[

It is worth mentioning that minimal retraction is seen after SCT and that in these cases PEG acts initially as a neuroprotectant (see below) and a bridge for regenerating axons across the gap. In the model suggested in this article, apposition is complete and PEG would also act as an axonal fusogen.[

In conclusion, PEG fusion is an ideal candidate for a clinical trial.

UNDERSTANDING SCT

To understand the fusion process, one has to first understand the cellular processes in play in the setting of SCT.

Yoshida et al.[

Ramon and Cajal[

In view of this data, it is obvious that whatever treatment must be brought to bear within minutes (<10).

FUSOGENS: THE ENGINE OF RECOVERY

Fusogens comprise a class of substances that have the capacity to reseal damaged cell membranes. Included in this class is PEG. PEG is a relatively inexpensive, stable, nontoxic, fully biocompatible, and water-soluble linear polymer that is synthesized by the living anionic ring-opening polymerization of ethylene oxide with molecular weights ranging from 0.4 to 100 kDa. It has a wide range of clinical and pharmaceutical applications, including, among others, an oral laxative, and several PEGylated drugs. PEG is FDA-approved for use as a preservative additive before organ transplantation to limit cold ischemia/reperfusion injury.[

PEG has been shown to be strongly neuroprotectant thanks to its membrane sealing/fusing properties [

Certainly, not all PEGs are created equal, and there is some evidence that molecular weight and other factors can influence the fusogenic potential and extent of recovery [

PEG has been combined with graphene nanofibers that are known to promore axonal regeneration.[

Another fusogen is chitosan, a nontoxic, biodegradable polycationic polymer with low immunogenicity that has been extensively investigated in various biomedical applications. Topical application of chitosan after complete transection of the guinea pig spinal cord facilitated sealing of damaged neuronal membranes and restored the conduction of nerve impulses through the length of spinal cords in vivo.[

THE ANATOMICAL BASIS OF SPINAL CORD FUSION

Although experiments show that PEG can refuse severed spinal cord fibers, yet the number is limited (10–15%); in addition, fibers are not matched at the moment of fusion. It can be argued that the reason for its effectiveness is mostly due to PEG neuroprotectant potential of the cord gray matter cellular milieu. In other words, PEG does not actually achieve its goal by refusing a large number of long-projection fibers in the white matter brought together by manipulation of the transected ends of the spinal cord[

In mammals, including monkeys and man, there exists a network of interneuronal cells located throughout the rostrocaudal length of the brainstem and spinal cord that conveys motor (and sensory) signals and that embeds and connects the brainstem, cervical and lumbar central pattern generators [so-called cortico-truncoreticulo-propriospinal system – CTRPS – or Motor Highway 2:

Spinal fusion is made possible because transection only minimally damages a thin layer of cells belonging to this matrix, allowing the gray matter neuropil to immediately resprout severed axons and dendrites (regenerative sprouting) at the interface of the apposed cords. It should be noted that a sharp transection typically generates <10 Newtons (N: SI unit of force) of force versus approximately 26,000 N experienced during clinical SCI, a 2600 times difference.[

An important concern is scarring after SCT. In all published studies, PEG has been applied immediately after SCT. Scarring becomes visible only after about 1 week: given a 1 mm/die regrowth rate, regenerating axons from both cord ends will have penetrated the opposite gray matter well by then (66 mm/h).[

Function will be restored also due to rewiring upstream in the central nervous system (CNS), so long as the mismatch is not extreme. Indeed, recovery from any anatomic disruption of the spinal cord utilizes the entire CNS, namely, cord, brainstem, and brain, in which a massive degree of reorganization (large-scale “rewiring”) occurs:[

PAIN AFTER SCT

SCI is followed in up to 40% of cases by so-called cord central pain (CCP).[

CCP is generally accompanied by hyperactivity in the TRPS pathway, which can be quelled by extensive neurosurgical destruction thereof at both brainstem and cord levels: pain is controlled to a major extent.[

CLINICAL TRANSLATION

Experimental evidence [Tables

Gemini

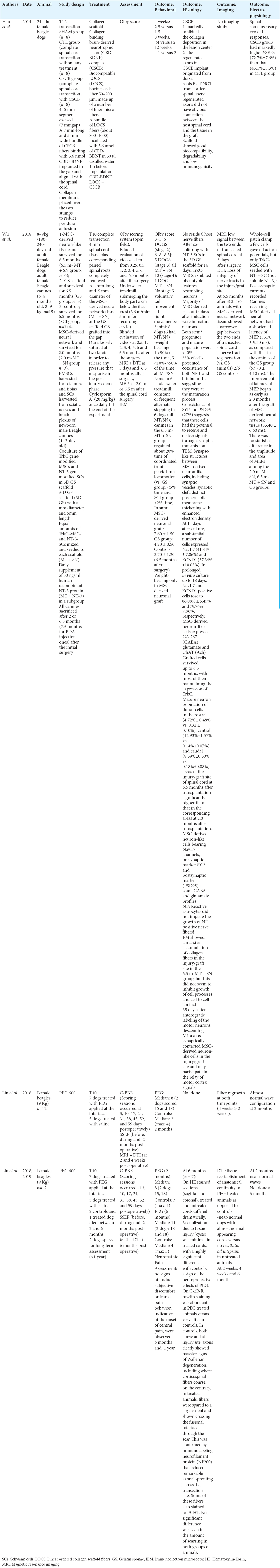

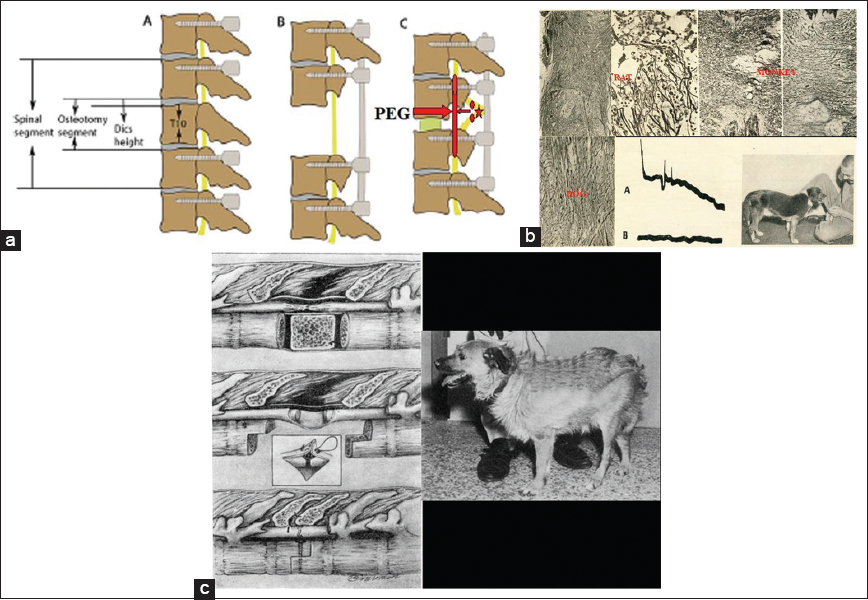

As discussed, Walter Freeman suggested the severance-reapposition model for chronic SCI; he removed the damaged segment of the cord in dogs creating a gap, performed a complete en bloc vertebrectomy thus shortening the spine, brought the two fresh cord stumps in contact with fresh plasma and sutured the dura tightly: walking animals resulted after several months. He observed direct electrophysiological conductance across the apposed stumps and provided histological evidence of axonal regeneration across the sectional interface [

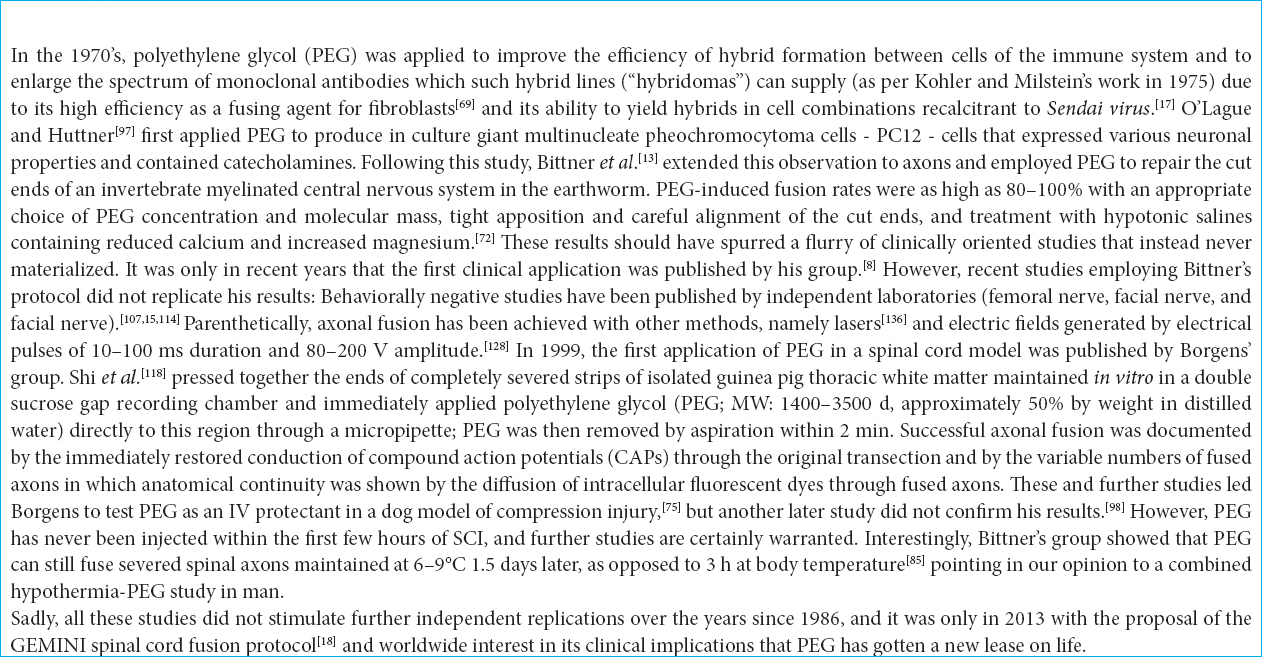

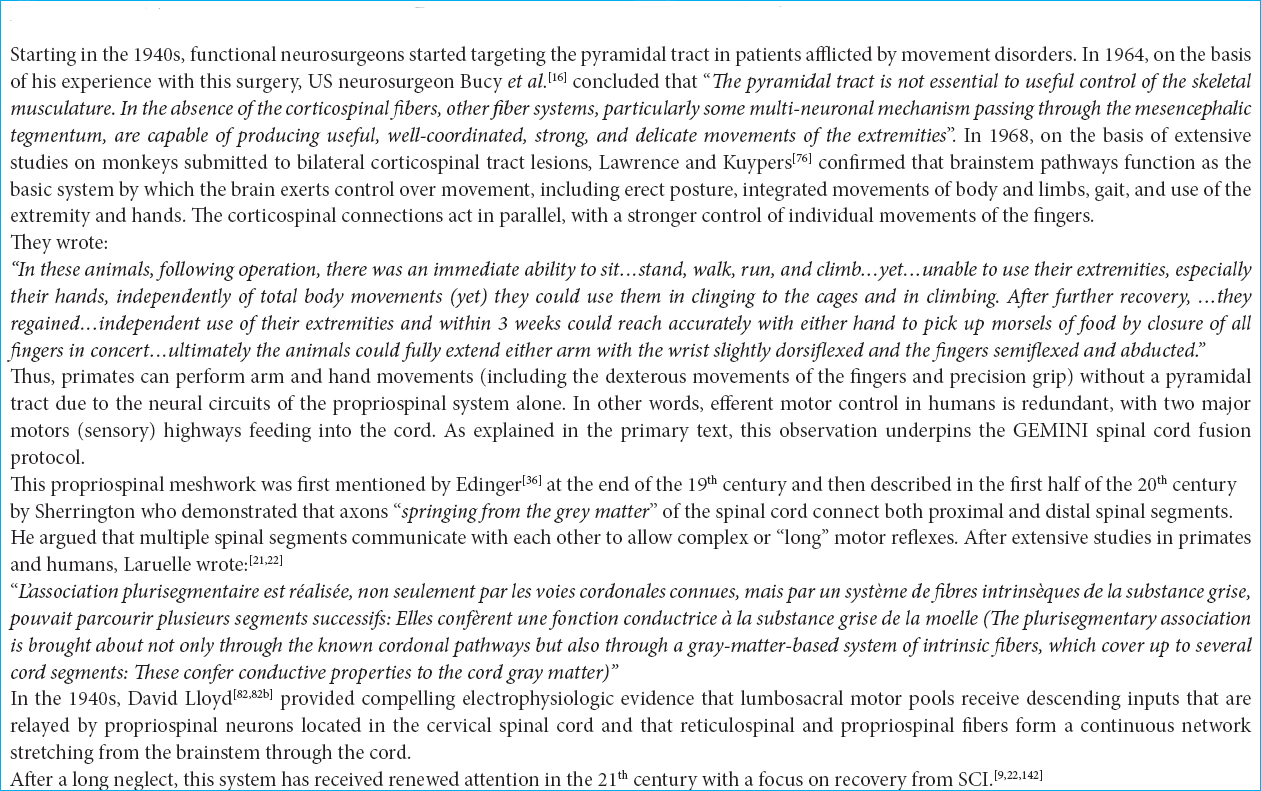

Figure 1

(a) Proposed model of removal of the injured segment (star), transection of the cord above and below (ovoids) and fusion with polyethylene glycol (arrow) along with vertebral shortening and stabilization (adapted from Qiu et al., 2015). (b)

Hydrogelation of the GAP

PEG can be cross-linked to form porous hydrogels, which can serve as biocompatible matrices that can closely mimic the ECM. This suggests another possibility that does not require a vertebrectomy: removing half of the damaged cord, up to its border with rostral and caudal healthy tissue and filling the void with a PEG hydrogel. PEG hydrogels have high water content and porosity, which make them behave like aqueous solutions at a microscopic scale while being macroscopically solid. In an easily tailorable process, these can be optimized by adding different reactive moieties to both ends of the PEG chain. Mosley et al.[

Fusion-supported cord grafting

The possibility of implanting a segment of healthy cord from an organ donor must be also entertained [

In this case, PEG would neuroprotect the tissue until vascularization from the healthy ends of the patient would feed the graft. Biomaterials can be effectively used for promoting and guiding blood vessel formation.[

PEG proxies

As mentioned, another effective fusogen is chitosan. Rao et al.[

A combination of both chitosan and PEG in hydrogels promise even better results.[

Electrical stimulation

As originally proposed,[

CONCLUSION

Removing the chronically injured segment of a cord, followed by spinal shortening and PEG fusion of the healthy ends (GEMINI protocol) has the potential to restore motor function in a substantial number of chronically paralyzed (ASIA A) patients for whom no cure is available.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Al Kandari S, Prasad L, Al Kandari M, Ramachandran U, Krassioukov A. Cell transplantation and clinical reality: Kuwait experience in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018. 56: 674-9

2. Amoozgar Z, Rickett T, Park J, Tuchek C, Shi R, Yeo Y. Semi-interpenetrating network of polyethylene glycol and photocrosslinkable chitosan as an in situ -forming nerve adhesive. Acta Biomater. 2012. 8: 1849-58

3. Angeli CA, Boakye M, Morton RA, Vogt J, Benton K, Chen Y. Recovery of over-ground walking after chronic motor complete spinal cord injury. N Engl J Med. 2018. 379: 1244-50

4. . Stab wounds of the spinal cord. Br Med J. 1978. 1: 1093-4

5. Aoun SG, Elguindy M, Barrie U, El Ahmadieh TY, Plitt A, Moreno JR. Four-level vertebrectomy for en bloc resection of a cervical chordoma. World Neurosurg. 2018. 118: 316-23

6. Assinck P, Duncan GJ, Hilton BJ, Plemel JR, Tetzlaff W. Cell transplantation therapy for spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2017. 20: 637-47

7. Bakshi A, Fisher O, Dagci T, Himes BT, Fischer I, Lowman A. Mechanically engineered hydrogel scaffolds for axonal growth and angiogenesis after transplantation in spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004. 1: 322-9

8. Bamba R, Waitayawinyu T, Nookala R, Riley DC, Boyer RB, Sexton KW. Anovel therapy to promote axonal fusion in human digital nerves. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016. 81: S177-S183

9. Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, Schwab ME. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004. 7: 269-77

10. Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. A sensitive and reliable locomotor rating scale for open field testing in rats. J Neurotrauma. 1995. 12: 1-21

11. Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp Neurol. 1996. 139: 244-56

12. Bitar Alatorre WE, Garcia Martinez D, Rosales Corral SA, Flores Soto ME, Velarde Silva G, Portilla de Buen E. Critical ischemia time in a model of spinal cord section. A study performed on dogs. Eur Spine J. 2007. 16: 563-72

13. Bittner GD, Ballinger ML, Raymond MA. Reconnection of severed nerve axons with polyethylene glycol. Brain Res. 1986. 367: 351-5

14. Brazda N, Voss C, Estrada V, Lodin H, Weinrich N, Seide K. Amechanical microconnector system for restoration of tissue continuity and long-term drug application into the injured spinal cord. Biomaterials. 2013. 34: 10056-64

15. Brown BL, Asante T, Welch HR, Sandelski MM, Drejet SM, Shah K. Functional and anatomical outcomes of facial nerve injury with application of polyethylene glycol in a rat model. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019. 21: 61-8

16. Bucy PC, Keplinger JE, Siqueira EB. Destruction of the “pyramidal tract” in man. J Neurosurg. 1964. 21: 285-98

17. Buttin G, LeGuern G, Phalente L, Cazenave PA, Melchers F, Potter M, Warner NL.editors. Production of hybrid lines secreting monoclonal anti-idiotypic antibodies by cell fusion on membrane filters. Lymphocyte Hybridomas. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1979. p. 27-36

18. Canavero S. HEAVEN: The head anastomosis venture project outline for the first human head transplantation with spinal linkage (GEMINI). Surg Neurol Int. 2013. 4: S335-42

19. Canavero S, Bonicalzi V.editorsCentral pain Syndrome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p.

20. Canavero S, Bonicalzi V.editorsCentral pain syndrome. Basingstoke: Springer-Nature; 2018. p.

21. Canavero S. The “Gemini” spinal cord fusion protocol: Reloaded. Surg Neurol Int. 2015. 6: 18-

22. Canavero S, Ren X, Kim CY, Rosati E. Neurologic foundations of spinal cord fusion (GEMINI). Surgery. 2016. 160: 11-9

23. Canavero S, Ren X. Houston, GEMINI has landed: Spinal cord fusion achieved. Surg Neurol Int. 2016. 7: S626-8

24. Canavero S, Ren XP. The spark of life: Engaging the cortico-truncoreticulo-propriospinal pathway by electrical stimulation. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016. 22: 260-1

25. Carpenter MB, Sutin J.editorsHuman Neuroanatomy. Philadelphia, PA: Williams and Wilkins; 1983. p.

26. Cha YH, Cho TH, Suh JK. Traumatic cervical cord transection without facet dislocations a proposal of combined hyperflexion-hyperextension mechanism: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2010. 25: 1247-50

27. Chen L, Huang H, Xi H, Zhang F, Liu Y, Chen D. Aprospective randomized double-blind clinical trial using a combination of olfactory ensheathing cells and Schwann cells for the treatment of chronic complete spinal cord injuries. Cell Transplant. 2014. 23: S35-44

28. Chhabra HS, Sarda K. Clinical translation of stem cell based interventions for spinal cord injury are we there yet?. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017. 120: 41-9

29. Chiu YC, Kocagöz S, Larson JC, Brey EM. Evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of porous poly (ethylene glycol)-co-(L-lactic acid) hydrogels during degradation. PLoS One. 2013. 8: e60728-

30. Cho Y, Shi R, Borgens RB. Chitosan produces potent neuroprotection and physiological recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury. J Exp Biol. 2010. 213: 1513-20

31. Dalamagkas K, Tsintou M, Seifalian A, Seifalian AM. Translational regenerative therapies for chronic spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2018. 19: e1776-

32. Dietz V, Schwab ME. From the rodent spinal cord injury model to human application: Promises and challenges. J Neurotrauma. 2017. 34: 1826-30

33. Dlouhy BJ, Dahdaleh NS, Howard MA. Radiographic and intraoperative imaging of a hemisection of the spinal cord resulting in a pure brown-séquard syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Sci. 2013. 57: 81-6

34. Donovan J, Kirshblum S. Clinical trials in traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2018. 15: 654-68

35. Dran G, Fontaine D, Litrico S, Grellier P, Paquis P. Stabwound of the cervical spinal cord. Two case reports. Neurochirurgie. 2005. 51: 476-80

36. Edinger L.editorsVorlesungen ueber den Bau der nervoesen Centralorgane des Menschen und der Thiere. Leipzig: Verlag von F.C.W, Vogel; 1896. p.

37. Estrada V, Brazda N, Schmitz C, Heller S, Blazyca H, Martini R. Long-lasting significant functional improvement in chronic severe spinal cord injury following scar resection and polyethylene glycol implantation. Neurobiol Dis. 2014. 67: 165-79

38. Feringa ER, Kowalski TF, Vahlsing HL. Basal lamina formation at the site of spinal cord transection. Ann Neurol. 1980. 8: 148-54

39. Freeman LW. Return of spinal cord function in mammals after transecting lesions. Ann NY Acad Med Sci. 1954. 58: 564-9

40. Freeman LW, Windle WF.editors. Functional recovery in spinal rats. Regeneration in the Central Nervous System. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas; 1955. p. 195-207

41. Freeman LW. Experimental observations upon axonal regeneration in the transected spinal cord of mammals. Clin Neurosurg. 1962. 8: 294-319

42. Freeman LW.editorsProceedings, X Congreso Latinoamericano de Neurochirurgia. Brazil: Editorial Don Bosco; 1963. p. 135-44

43. Friedli L, Rosenzweig ES, Barraud Q, Schubert M, Dominici N, Awai L. Pronounced species divergence in corticospinal tract reorganization and functional recovery after lateralized spinal cord injury favors primates. Sci Transl Med. 2015. 7: 302ra134-

44. Garay RP, El-Gewely R, Armstrong JK, Garratty G, Richette P. Antibodies against polyethylene glycol in healthy subjects and in patients treated with PEG-conjugated agents. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2012. 9: 1319-23

45. Gill ML, Grahn PJ, Calvert JS, Linde MB, Lavrov IA, Strommen JA. Neuromodulation of lumbosacral spinal networks enables independent stepping after complete paraplegia. Nat Med. 2018. 24: 1677-82

46. Goldsmith HS, Fonseca A, Porter J. Spinal cord separation: MRI evidence of healing after omentum-collagen reconstruction. Neurol Res. 2005. 27: 115-23

47. Guertin PA. Semiquantitative assessment of hindlimb movement recovery without intervention in adult paraplegic mice. Spinal Cord. 2005. 43: 162-6

48. Haggerty AE, Maldonado-Lasunción I, Oudega M. Biomaterials for revascularization and immunomodulation after spinal cord injury. Biomed Mater. 2018. 13: 044105-

49. Handa Y, Naito A, Watanabe S, Komatsu S, Shimizu Y. Functional recovery of locomotive behavior in the adult spinal dog. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1986. 148: 373-84

50. Hardy JG, Lin P, Schmidt CE. Biodegradable hydrogels composed of oxime crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol), hyaluronic acid and collagen: A tunable platform for soft tissue engineering. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2015. 26: 143-61

51. Heimburger RF. Return of function after spinal cord transection. Spinal Cord. 2005. 43: 438-40

52. Heimburger RF. Is there hope for return of function in lower extremities paralyzed by spinal cord injury?. J Am Coll Surg. 2006. 202: 1001-4

53. Hoffman AN, Bamba R, Pollins AC, Thayer WP. Analysis of polyethylene glycol (PEG) fusion in cultured neuroblastoma cells via flow cytometry: Techniques and optimization. J Clin Neurosci. 2017. 36: 125-8

54. Hsieh PC, Stapleton CJ, Moldavskiy P, Koski TR, Ondra SL, Gokaslan ZL. Posterior vertebral column subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of tethered cord syndrome: Review of the literature and clinical outcomes of all cases reported to date. Neurosurg Focus. 2010. 29: E6-

55. Illis LS. Central nervous system regeneration does not occur. Spinal Cord. 2012. 50: 259-63

56. Imaninezhad M, Pemberton K, Xu F, Kalinowski K, Bera R, Zustiak SP. Directed and enhanced neurite outgrowth following exogenous electrical stimulation on carbon nanotube-hydrogel composites. J Neural Eng. 2018. 15: 56034-

57. Isa T. The brain is needed to cure spinal cord injury. Trends Neurosci. 2017. 40: 625-36

58. Iseda T, Nishio T, Kawaguchi S, Yamanoto M, Kawasaki T, Wakisaka S. Spontaneous regeneration of the corticospinal tract after transection in young rats: A key role of reactive astrocytes in making favorable and unfavorable conditions for regeneration. Neuroscience. 2004. 126: 365-74

59. Iwatsuki K, Tajima F, Sankai Y, Ohnishi YI, Nakamura T, Ishihara M. Motor evoked potential and voluntary EMG activity after olfactory mucosal autograft transplantation in a case of chronic, complete spinal cord injury: Case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2016. 2: 15018-

60. James ND, McMahon SB, Field-Fote EC, Bradbury EJ. Neuromodulation in the restoration of function after spinal cord injury. Lancet Neurol. 2018. 17: 905-17

61. Jiang G, Sun J, Ding F. PEG-g-chitosan thermosensitive hydrogel for implant drug delivery: Cytotoxicity in vivo degradation and drug release. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2014. 25: 241-56

62. Kao CC, Wirile WF.editors. Spinal cord cavitation after injury. The Spinal Cord and Its Reaction to Traumatic Injury. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1980. p. 249-70

63. Kerschensteiner M, Schwab ME, Lichtman JW, Misgeld T. In vivo imaging of axonal degeneration and regeneration in the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2005. 11: 572-7

64. Kim CY. PEG-assisted reconstruction of the cervical spinal cord in rats: Effects on motor conduction at 1 h. Spinal Cord. 2016. 54: 910-2

65. Kim CY, Sikkema WK, Hwang IK, Oh H, Kim UJ, Lee BH. Spinal cord fusion with PEG-GNRs (TexasPEG): Neurophysiological recovery in 24 hours in rats. Surg Neurol Int. 2016. 7: S632-6

66. Kim CY, Oh H, Ren X, Canavero S. Immunohistochemical evidence of axonal regrowth across polyethylene glycol-fused cervical cords in mice. Neural Regen Res. 2017. 12: 149-50

67. Kim CY, Sikkema WKA, Kim J, Kim JA, Walter J, Dieter R. Effect of graphene nanoribbons (TexasPEG) on locomotor function recovery in a rat model of lumbar spinal cord transection. Neural Regen Res. 2018. 13: 1440-6

68. Kishk NA, Gabr H, Hamdy S, Afifi L, Abokresha N, Mahmoud H. Case control series of intrathecal autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell therapy for chronic spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010. 24: 702-8

69. Knutton S, Pasternak CA. The mechanism of cell-cell fusion. Trends Biochem Sci. 1979. 4: 220-3

70. Kong XB, Tang QY, Chen XY, Tu Y, Sun SZ, Sun ZL. Polyethylene glycol as a promising synthetic material for repair of spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2017. 12: 1003-8

71. Kouhzaei S, Rad I, Mousavidoust S, Mobasheri H. Protective effect of low molecular weight polyethylene glycol on the repair of experimentally damaged neural membranes in rat's spinal cord. Neurol Res. 2013. 35: 415-23

72. Krause TL, Bittner GD. Rapid morphological fusion of severed myelinated axons by polyethylene glycol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990. 87: 1471-5

73. Lampe KJ, Kern DS, Mahoney MJ, Bjugstad KB. The administration of BDNF and GDNF to the brain via PLGA microparticles patterned within a degradable PEG-based hydrogel: Protein distribution and the glial response. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011. 96: 595-607

74. Lao LF, Zhong GB, Liu ZD. Transection of double-level spinal cord without radiographic abnormalities in an adult: A case report. Orthop Surg. 2013. 5: 302-4

75. Laverty PH, Leskovar A, Breur GJ, Coates JR, Bergman RL, Widmer WR. Apreliminary study of intravenous surfactants in paraplegic dogs: Polymer therapy in canine clinical SCI. J Neurotrauma. 2004. 21: 1767-77

76. Lawrence DG, Kuypers HG. The functional organization of the motor system in the monkey. II. The effects of lesions of the descending brain-stem pathways. Brain. 1968. 91: 15-36

77. Lee HM, Kim NH, Park CI. Spinal cord injury caused by a stab wound a case report. Yonsei Med J. 1990. 31: 280-4

78. Lee SH, Chung YN, Kim YH, Kim YJ, Park JP, Kwon DK. Effects of human neural stem cell transplantation in canine spinal cord hemisection. Neurol Res. 2009. 31: 996-1002

79. Li X, Yang B, Xiao Z, Zhao Y, Han S, Yin Y. Comparison of subacute and chronic scar tissues after complete spinal cord transection. Exp Neurol. 2018. 306: 132-7

80. Liu Z, Ren S, Fu K, Wu Q, Wu J, Hou L. Restoration of motor function after operative reconstruction of the acutely transected spinal cord in the canine model. Surgery. 2018. 163: 976-83

81. Ren S, Liu Z, Kim CY, Fu K, Wu Q, Hou L. Reconstruction of the spinal cord of spinal transected dogs with polyethylene glycol. Surg Neurol Int. 2019. 10: 50-

82. Lloyd DP. Activity in neurons of the bulbospinal correlation system. J Neurophysiol. 1941. 4: 115-34

83. Lloyd DP. Mediation of descending long spinal reflex activity. J Neurophysiol. 1942. 5: 435-58

84. Lu X, Perera TH, Aria AB, Callahan LAS. Polyethylene glycol in spinal cord injury repair: A critical review. J Exp Pharmacol. 2018. 10: 37-49

85. Manzone P, Domenech V, Forlino D. Stab injury of the spinal cord surgically treated. J Spinal Disord. 2001. 14: 264-7

86. Marzullo TC, Britt JM, Stavisky RC, Bittner GD. Cooling enhances in vitro survival and fusion-repair of severed axons taken from the peripheral and central nervous systems of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002. 327: 9-12

87. McMahill BG, Borjesson DL, Sieber-Blum M, Nolta JA, Sturges BK. Stem cells in canine spinal cord injury promise for regenerative therapy in a large animal model of human disease. Stem Cell Rev. 2015. 11: 180-93

88. Mody GN, Bravo Iñiguez C, Armstrong K, Perez Martinez M, Ferrone M, Bono C. Early surgical outcomes of en bloc resection requiring vertebrectomy for malignancy invading the thoracic spine. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016. 101: 231-6

89. Mohrman AE, Farrag M, Grimm RK, Leipzig ND. Evaluation of in situ gelling chitosan-PEG copolymer for use in the spinal cord. J Biomater Appl. 2018. 33: 435-46

90. Mosley MC, Lim HJ, Chen J, Yang YH, Li S, Liu Y. Neurite extension and neuronal differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cell derived neural stem cells on polyethylene glycol hydrogels containing a continuous young's modulus gradient. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017. 105: 824-33

91. Nakajima N, Ikada Y. Effects of concentration, molecular weight, and exposure time of poly(ethylene glycol) on cell fusion. Polymer J. 1995. 27: 211-9

92. Nardone R, Florea C, Höller Y, Brigo F, Versace V, Lochner P. Rodent, large animal and non-human primate models of spinal cord injury. Zoology (Jena). 2017. 123: 101-14

93. Nawrotek K, Marqueste T, Modrzejewska Z, Zarzycki R, Rusak A, Decherchi P. Thermogelling chitosan lactate hydrogel improves functional recovery after a C2 spinal cord hemisection in rat. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017. 105: 2004-19

94. Nehrt A, Hamann K, Ouyang H, Shi R. Polyethylene glycol enhances axolemmal resealing following transection in cultured cells and in ex vivo spinal cord. J Neurotrauma. 2010. 27: 151-61

95. Nishio T, Fujiwara H, Kanno I. Immediate elimination of injured white matter tissue achieves a rapid axonal growth across the severed spinal cord in adult rats. Neurosci Res. 2018. 131: 19-29

96. Noble LJ, Maxwell DS. Blood-spinal cord barrier response to transection. Exp Neurol. 1983. 79: 188-99

97. Oda Y, Tani K, Isozaki A, Haraguchi T, Itamoto K, Nakazawa H. Effects of polyethylene glycol administration and bone marrow stromal cell transplantation therapy in spinal cord injury mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2014. 76: 415-21

98. O'Lague PH, Huttner SL. Physiological and morphological studies of rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12) chemically fused and grown in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980. 77: 1701-5

99. Olby NJ, Muguet-Chanoit AC, Lim JH, Davidian M, Mariani CL, Freeman AC. Aplacebo-controlled, prospective, randomized clinical trial of polyethylene glycol and methylprednisolone sodium succinate in dogs with intervertebral disk herniation. J Vet Intern Med. 2016. 30: 206-14

100. Ozawa H, Matsumoto T, Ohashi T, Sato M, Kokubun S. Comparison of spinal cord gray matter and white matter softness: Measurement by pipette aspiration method. J Neurosurg. 2001. 95: 221-4

101. Pasut G, Panisello A, Folch-Puy E, Lopez A, Castro-Benítez C, Calvo M. Polyethylene glycols: An effective strategy for limiting liver ischemia reperfusion injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2016. 22: 6501-8

102. Qiu F, Yang JC, Ma XY, Xu JJ, Yang QL, Zhou X. Relationship between spinal cord volume and spinal cord injury due to spinal shortening. PLoS One. 2015. 10: e0127624-

103. Ramon Y, Cajal S.editorsDegeneration and Regeneration in the Nervous System. New York: Haffner Press; 1928. p.

104. Rao YJ, Zhu WX, Du ZQ, Jia CX, Du TX, Zhao QA. Effectiveness of olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation for treatment of spinal cord injury. Genet Mol Res. 2014. 13: 4124-9

105. Rao JS, Zhao C, Zhang A, Duan H, Hao P, Wei RH. NT3-chitosan enables de novo regeneration and functional recovery in monkeys after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018. 115: E5595-604

106. Richter-Turtur M, Krueger P, Wilker D, Angstwurm H. Cervical transverse spinal cord injury caused by knife stab injury. Unfallchirurg. 1990. 93: 4-5

107. Riley DC, Bittner GD, Mikesh M, Cardwell NL, Pollins AC, Ghergherehchi CL. Polyethylene glycol-fused allografts produce rapid behavioral recovery after ablation of sciatic nerve segments. J Neurosci Res. 2015. 93: 572-83

108. Robinson GA, Madison RD. Polyethylene glycol fusion repair prevents reinnervation accuracy in rat peripheral nerve. J Neurosci Res. 2016. 94: 636-44

109. Rodemer W, Selzer ME. Role of axon resealing in retrograde neuronal death and regeneration after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2019. 14: 399-404

110. Rolls A, Shechter R, Schwartz M. The bright side of the glial scar in CNS repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009. 10: 235-41

111. Rosenzweig ES, Brock JH, Lu P, Kumamaru H, Salegio EA, Kadoya K. Restorative effects of human neural stem cell grafts on the primate spinal cord. Nat Med. 2018. 24: 484-90

112. Rossignol S, Barrière G, Alluin O, Frigon A. Re-expression of locomotor function after partial spinal cord injury. Physiology (Bethesda). 2009. 24: 127-39

113. Rubin G, Tallman D, Sagan L, Melgar M. An unusual stab wound of the cervical spinal cord: A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001. 26: 444-7

114. Sahni V, Kessler JA. Stem cell therapies for spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010. 6: 363-72

115. Salomone R, Jácomo AL, Nascimento SB, Lezirovitz K, Hojaij FC, Costa HJ. Polyethylene glycol fusion associated with antioxidants: A new promise in the treatment of traumatic facial paralysis. Head Neck. 2018. 40: 1489-97

116. Sawada M, Kato K, Kunieda T, Mikuni N, Miyamoto S, Onoe H. Function of the nucleus accumbens in motor control during recovery after spinal cord injury. Science. 2015. 350: 98-101

117. Sengupta P. The laboratory rat: Relating its age with human's. Int J Prev Med. 2013. 4: 624-30

118. Shahlaie K, Chang DJ, Anderson JT. Nonmissile penetrating spinal injury. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006. 4: 400-8

119. Shi R, Borgens RB, Blight AR. Functional reconnection of severed mammalian spinal cord axons with polyethylene glycol. J Neurotrauma. 1999. 16: 727-38

120. Shirres DA. Regeneration of the spinal neurones in man. Montreal Med J. 1905. 34: 239-

121. Siddiqui AM, Khazaei M, Fehlings MG. Translating mechanisms of neuroprotection, regeneration, and repair to treatment of spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res. 2015. 218: 15-54

122. Sikkema WKA, Metzger AB, Wang T, Tour JM. Physical and electrical characterization of texasPEG: An electrically conductive neuronal scaffold. Surg Neurol Int. 2017. 8: 84-

123. Sledge J, Graham WA, Westmoreland S, Sejdic E, Miller A, Hoggatt A. Spinal cord injury models in non human primates: Are lesions created by sharp instruments relevant to human injuries?. Med Hypotheses. 2013. 81: 747-8

124. Steinberg JA, Wali AR, Martin J, Santiago-Dieppa DR, Gonda D, Taylor W. Spinal shortening for recurrent tethered cord syndrome via a lateral retropleural approach: A Novel operative technique. Cureus. 2017. 9: e1632-

125. Stewart FT, Harte RH. A case of severed spinal cord in which myelorrhaphy was followed by partial return of function. Med J. 1902. 9: 1016-20

126. Tabakow P, Raisman G, Fortuna W, Czyz M, Huber J, Li D. Functional regeneration of supraspinal connections in a patient with transected spinal cord following transplantation of bulbar olfactory ensheathing cells with peripheral nerve bridging. Cell Transplant. 2014. 23: 1631-55

127. Takahashi I, Iwasaki Y, Abumiya T, Imamura H, Houkin K, Saitoh H. Stab wounds of the spinal cord by a kitchen knife: Report of a case. No Shinkei Geka. 1991. 19: 255-8

128. Thornton MA, Mehta MD, Morad TT, Ingraham KL, Khankan RR, Griffis KG. Evidence of axon connectivity across a spinal cord transection in rats treated with epidural stimulation and motor training combined with olfactory ensheathing cell transplantation. Exp Neurol. 2018. 309: 119-33

129. Todorov AT, Yogev D, Qi P, Fendler JH, Rodziewicz GS. Electric-field-induced reconnection of severed axons. Brain Res. 1992. 582: 329-34

130. Wang A, Huo X, Zhang G, Wang X, Zhang C, Wu C. Effect of DSPE-PEG on compound action potential, injury potential and ion concentration following compression in ex vivo spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 2016. 620: 50-6

131. Wang A, Zhang G, Xiaochen W, Zhang C, Tao S, Huo XPaper Presented at: 2016 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC). 2016. p. 17-21

132. Wang GD, Zhai W, Yang HC, Fan RX, Cao X, Zhong L. The genomics of selection in dogs and the parallel evolution between dogs and humans. Nat Commun. 2013. 4: 1860-

133. Willyard C. A time to heal. Nature. 2013. 503: S4-6

134. Wu GH, Shi HJ, Che MT, Huang MY, Wei QS, Feng B. Recovery of paralyzed limb motor function in canine with complete spinal cord injury following implantation of MSC-derived neural network tissue. Biomaterials. 2018. 181: 15-34

135. Xiao Z, Tang F, Tang J, Yang H, Zhao Y, Chen B. One-year clinical study of neuroregen scaffold implantation following scar resection in complete chronic spinal cord injury patients. Sci China Life Sci. 2016. 59: 647-55

136. Ye Y, Kim CY, Miao Q, Ren X. Fusogen-assisted rapid reconstitution of anatomophysiologic continuity of the transected spinal cord. Surgery. 2016. 160: 20-5

137. Yogev D, Todorov AT, Qi P, Fendler JH, Rodziewicz GS. Laser-induced reconnection of severed axons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991. 180: 874-80

138. Yoon C, Tuszynski MH. Frontiers of spinal cord and spine repair: Experimental approaches for repair of spinal cord injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012. 760: 1-5

139. Yoshida Y, Kataoka H, Kanchiku T, Suzuki H, Imajyo Y, Kato H. Transection method for shortening the rat spine and spinal cord. Exp Ther Med. 2013. 5: 384-8

140. Zhang G, Rodemer W, Lee T, Hu J, Selzer ME. The effect of axon resealing on retrograde neuronal death after spinal cord injury in lamprey. Brain Sci. 2018. 8: 65-

141. Zhang J, Lu X, Feng G, Gu Z, Sun Y, Bao G. Chitosan scaffolds induce human dental pulp stem cells to neural differentiation: Potential roles for spinal cord injury therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2016. 366: 129-42

142. Zhang S, Johnston L, Zhang Z, Ma Y, Hu Y, Wang J. Restoration of stepping-forward and ambulatory function in patients with paraplegia: Rerouting of vascularized intercostal nerves to lumbar nerve roots using selected interfascicular anastomosis. Surg Technol Int. 2003. 11: 244-8

143. Zholudeva LV, Qiang L, Marchenko V, Dougherty KJ, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Lane MA. The aneuroplastic and therapeutic potential of spinal interneurons in the injured spinal cord. Trends Neurosci. 2018. 41: 625-39

Harry S. Goldsmith, M.D.

Posted April 8, 2019, 3:41 pm

Dr. Ren’s report regarding spinal cord regeneration is interesting and worthy of future study and research. The removal of a spinal cord segment followed by application of polyethylene glycol (peg) to the cut ends of a transected spinal cord, in addition to vertebral osteotomy, appears to require additional basic research. The reason for this is that prior to patient surgery it must be established that axons actually cross the spinal cord transection site and travel distally down the spinal cord to connect with appropriate neural elements.

Dr. Ren reported the importance of the sharpness of the cutting blade that transects the spinal cord. The sharpness of a cutting-edge razor prompted a trip to the Gillette Razor headquarters in Boston where the sharpest blades that had ever been produced were obtained. It was later learned that even more essential than a sharp blade was the rigidity of the spinal cord prior to spinal cord transection.

A simple technique to induce spinal cord rigidity is accomplished by placing ice-saline sludge on the spinal cord ten minutes before transection. Following transection, the ice-saline sludge is further applied for fifteen minutes to the cut edges of the transected spinal cord, thus preventing axoplasmic flow from the cut edges of the spinal cord.

For additional comments regarding Dr. Ren’s work, refer to his related article titled “Reconstruction of the spinal cord of spinal-transected dogs with polyethylene glycol” In Surgical Neurology International, 26-MAR-2019;10:50).