- Department of Neurosurgery, Neurosurgery Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq,

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Baghdad, College of Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq,

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Al-Iraqia, College of Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq,

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Samer S. Hoz, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_957_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Muthanna N. Abdulqader1, Mustafa Ismail2, Aktham O. Al-Khafaji2, Teeba A. Al-Ageely2, Zahraa M. Kareem2, Ruqayah A. Al-Baider2, Sama S. Albairmani3, Fatimah Ayad2, Samer S. Hoz4. Brown-Sequard syndrome associated with a spinal cord injury caused by a retained screwdriver: A case report and literature review. 11-Nov-2022;13:520

How to cite this URL: Muthanna N. Abdulqader1, Mustafa Ismail2, Aktham O. Al-Khafaji2, Teeba A. Al-Ageely2, Zahraa M. Kareem2, Ruqayah A. Al-Baider2, Sama S. Albairmani3, Fatimah Ayad2, Samer S. Hoz4. Brown-Sequard syndrome associated with a spinal cord injury caused by a retained screwdriver: A case report and literature review. 11-Nov-2022;13:520. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11996/

Abstract

Background: Nonmissile penetrating spine injury (NMPSI) represents a small percent of spinal cord injuries (SCIs), estimated at 0.8% in Western countries. Regarding the causes, an NMPSI injury caused by a screwdriver is rare. This study reports a case of a retained double-headed screwdriver in a 37-year-old man who sustained a stab injury to the back of the neck, leaving the patient with a C4 Brown-Sequard syndrome (BSS). We discuss the intricacies of the surgical management of such cases with a literature review.

Methods: PubMed database was searched by the following combined formula of medical subjects headings, (MESH) terms, and keywords: (((SCIs [MeSH Terms]) OR (nmpsi [Other Term]) OR (nonmissile penetrating spinal injury [Other Term]) OR (nonmissile penetrating spinal injury [Other Term])) AND (BSS [MeSH Terms])) OR (BSS [MeSH Terms]).

Results: A total of 338 results were found; 258 were case reports. After excluding nonrelated cases, 16 cases were found of BSS induced by spinal cord injury by a retained object. The male-to-female ratio in these cases is 11:5, and ages ranged from 11 to 72. The causes of spinal cord injury included screwdrivers in three cases, knives in five cases, and glass in three cases. The extracted data were analyzed.

Conclusion: Screwdriver stabs causing cervical SCIs are extremely rare. This is the first case from Iraq where the assault device is retained in situ at the time of presentation. Such cases should be managed immediately to carefully withdraw the object under direct vision and prevent further neurological deterioration.

Keywords: Brown-Sequard syndrome, Retained foreign body, Screwdriver, Spinal cord injury

INTRODUCTION

Nonmissile penetrating spine injury (NMPSI) represents a very small percent of spinal cord injuries (SCI), estimated at 0.8% in Western countries, but can go up to 26% in countries like South Africa where the rates of street violence are high.[

The authors report a case of a retained double-headed screwdriver in a 37-year-old man who sustained a stab injury to the back of the neck, leaving the patient with a C4 BSS. We discuss the intricacies of the surgical management of such cases with a literature review of the related cases.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 37-year-old male presented to the emergency department after an assault and injury to the back of the neck with a double-headed screwdriver while the patient was leaning forward [

On examination, the patient was alert with a GCS of 15, laying in a prone position; the screwdriver was impacted in the back of the neck and hardly fixed, with minor bleeding around the inlet. The patient had right-sided hemiplegia (upper and lower limbs), Medical Research Council Grade 0/5 with loss of vibration and proprioception on the same side, and loss of pain and temperature sensation on the contralateral side of the body (Brown-Sequard injury), and urinary retention, which necessitated the insertion of a Foley catheter.

Cervical computed tomography (CT) scan showed the screwdriver going through the right lamina of C4 and entering the dura and the spinal cord, the tip reaching just medial to the transverse foramen of C4 [

Figure 2:

(a) Sagittal computed tomography (CT) of the cervical spine indicates the position of the tip of the screwdriver at the level of C4. (b) Axial CT of cervical spine scan demonstrating the screwdriver going through the right lamina and entering the dura and the spinal cord, the tip reaching just medial to the lateral mass and transverse foramen.

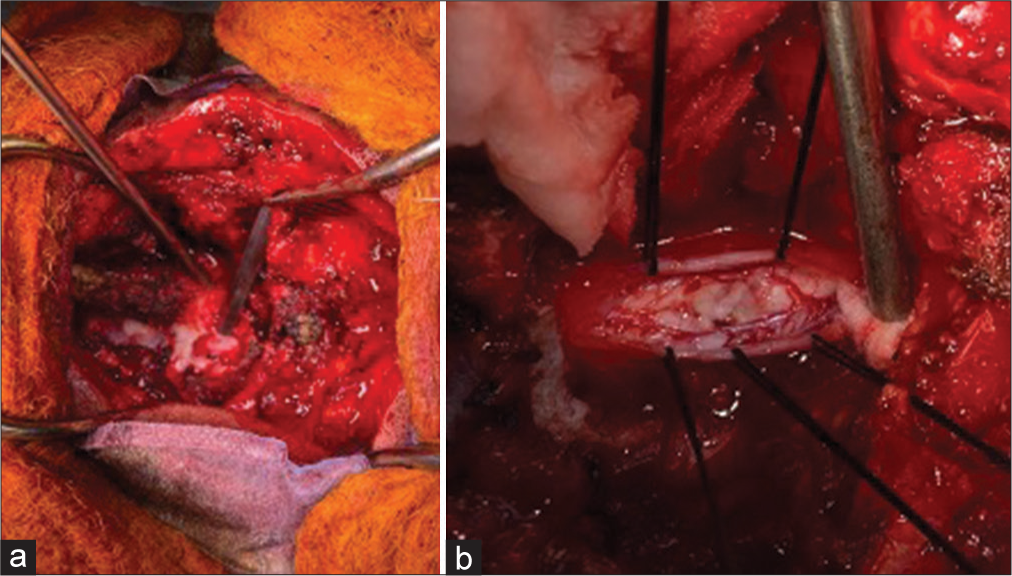

The patient was taken to the operating room immediately. Under general anesthesia (tube in a lateral position), surgical exploration was performed by a midline skin incision from C1 to C7 with dissection of the fascia and muscle to reach the screwdriver entrance. C4–C5 laminectomy was performed, the ligamentum flavum was removed [

Postoperatively, motor function on the right side of the body improved (upper limb Grade 2 and lower limb Grade 3). Seven days later, the right-sided weakness improved to Grade 3 in the upper limb and Grade 4 in the lower limb, and the urine catheter was removed as the patient regained urinary continence. However, there was no improvement in sensation. The postoperative cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mixed-intensity lesion in the posterior aspect of the spinal cord at the level of injury, suggesting a spinal cord contusion [

LITERATURE REVIEW

Methods

We conducted a PubMed database search by the following combined formula of medical subject headings, [MESH] terms, and keywords: (((SCIs [MeSH Terms]) OR (nmpsi [Other Term]) OR (nonmissile penetrating spinal injury [Other Term]) OR (nonmissile penetrating spinal injury [Other Term])) AND (BSS [MeSH Terms])) OR (BSS [MeSH Terms]).

RESULTS

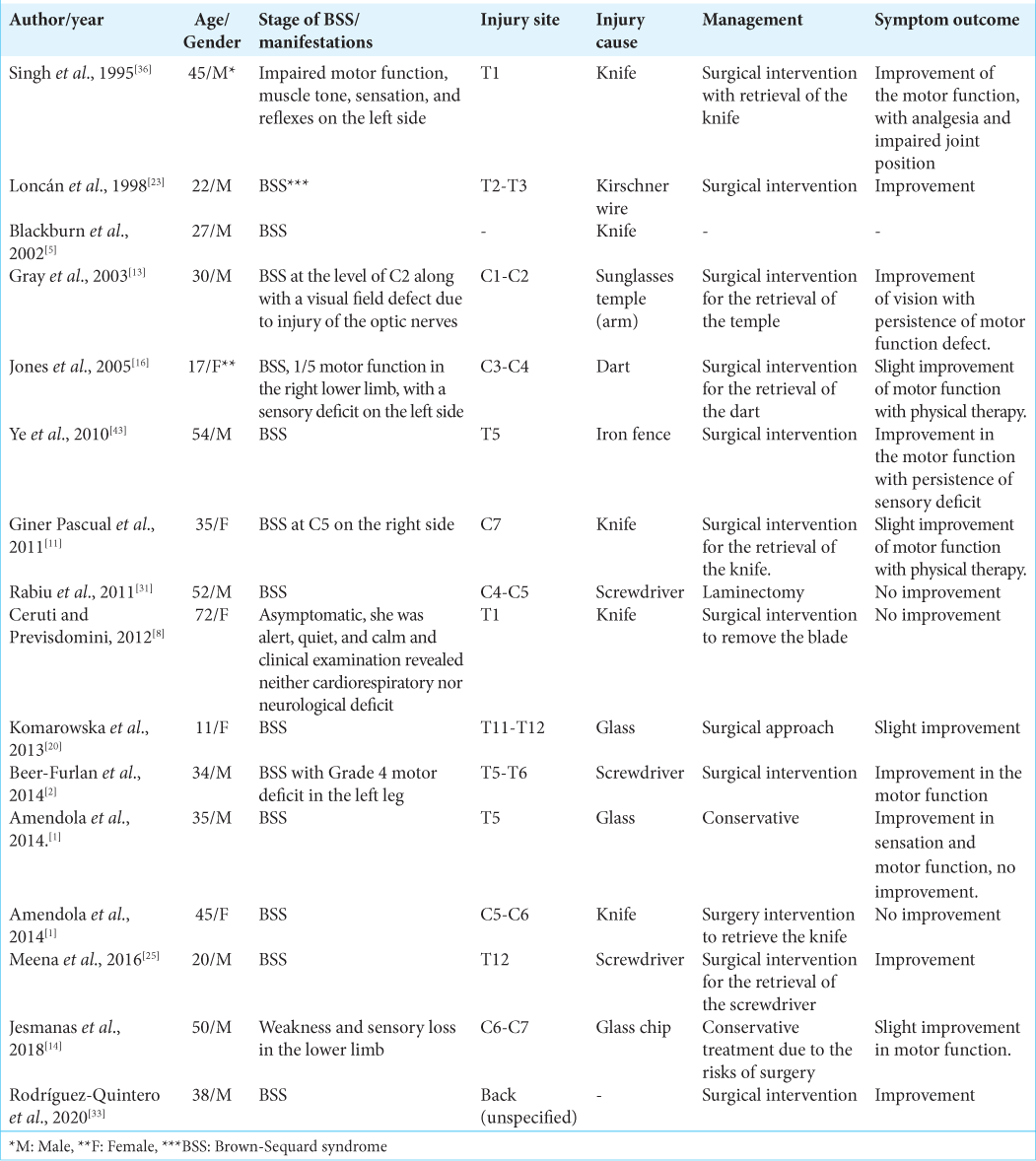

A total of 338 results were found; 258 were case reports. By excluding cases of nonretained objects causing spinal cord injury at the time of presentation, and the cases with noninjury induced BSS, we have found 16 reported cases of BSS induced by spinal cord injury by a retained object.

The male-to-female ratio in these cases is 11:5, and ages ranged from 11 to 72. The causes of spinal cord injury included screwdrivers in three cases, knives in five cases, and glass in three cases. Other objects included; sunglasses, dart, iron fence, and Kirschner wire. Thirteen of the reported cases were managed by an operative procedure to decompress the spinal cord and retrieve the causative objects, and two of the cases were conservatively treated.

Improvement was observed during the follow-up period in 12 of the reported cases, while three of the cases reported no improvement in motor and sensory functions or deterioration postoperatively [

DISCUSSION

In 1977, Peacock et al. reported a total of 450 spinal cord stab injuries, a publication that remains the major study on the subject thus far. About 26% of all spine assaults they managed over 13 years were attributed to stab injuries.[

These stabbing injuries mainly occur in the thoracic spine (61%) and least in the lumbar spine (7%).[

Screwdriver impaling in the context of NMPSI is particularly dangerous due to the concentrated force applied to a small area and the forceful stem penetrating the bone deeply. In contrast, stabs with knives tend to deflect and slide sideways by the effect of multiple muscle layers and bony spinal column or snap without penetrating the spinal canal.[

When the penetrating object is left in place, as in the present case, certain aspects of managing such injuries become quite challenging, such as patient transfer and positioning. Avoiding withdrawal or the slightest movement of retained objects before obtaining imaging and consultation is necessary. A complete neurological assessment must be done immediately to monitor any further neurological damage caused by patient handling, hemorrhage, or infection. Secondary injuries, including vascular injuries, must be ruled out, mainly following stabs to the cervical and dorsal spine.[

The imaging modality of choice in NMPSI is a CT scan, which has a high sensitivity for foreign bodies, spinal hematomas, and bony fractures. In emergency settings, a CT scan is also preferred due to its short acquisition time. MRI is not recommended in the case of retained metallic objects, as it can worsen the deficits, incite movement of the metallic foreign body, and even heat it, causing thermal injury to the spinal cord and surrounding structures.[

Operative management is somewhat controversial when it comes to NMPSI. Surgical exploration must be attempted in incomplete neurological deficits, spinal instability, retained foreign body, persistent leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), CSF fistula, and persistent pain. In cases of retained objects, immediate exploration is advised to avoid any infections and neurological deterioration.[

In our case, the operation decision was straightforward, as the screwdriver was retained. Surgical exploration was challenging to remove the object safely under direct vision without altering the neurological status and to prevent any possible secondary damage. The complications may include bleeding from epidural venous plexus, spinal traction injury, and CSF leakage.

According to Meena et al., the literature only documents five cases of BSS in the setting of retained foreign material in penetrating SCIs, with their case being the sixth reported up to the time of its publication.[

Late complications following incomplete spinal cord injury due to retained foreign objects may occur, including intramedullary abscess, myelopathy, progressive neurological deterioration, and symptomatic pseudomeningocele.[

In penetrating spinal injuries resulting in BSS, the prognosis relies on the severity, extent of damage to the spinal cord, and whether it has an associated secondary (i.e., vascular) injury.[

In summary, this is the first case from Iraq where the assault device is retained in situ at the presentation time. Neurological deterioration can be prevented by managing such cases immediately by carefully withdrawing the object under direct vision.

CONCLUSION

Cervical SCIs caused by screwdriver stabs are extremely rare occurrences. We report the first such case from Iraq, where the assault device is retained in situ at the time of presentation. Such cases must be operated on immediately to carefully withdraw the object under direct vision and prevent further neurological deterioration and catastrophic outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Amendola L, Corghi A, Cappuccio M, De Iure F. Two cases of Brown-Séquard syndrome in penetrating spinal cord injuries. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014. 18: 2-7

2. Beer-Furlan AL, Paiva WS, Tavares WM, de Andrade AF, Teixeira MJ. Brown-Sequard syndrome associated with unusual spinal cord injury by a screwdriver stab wound. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014. 7: 316-9

3. Bhatoe HS. Stabbed in the back. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2007. 4: 9-10

4. Bhutta MA, Dunkow PD, Lang DM. A stab in the back with a screwdriver: A case report. Cases J. 2008. 1: 305

5. Blackburn D, Werring DJ, Connor SE, Munro N, Bajaj NP. An eponymous reaction to a knife wound. Postgrad Med J. 2002. 78: 376-80

6. Boukobza M, Guichard JP, Boissonet M, George B, Reizine D, Gelbert F. Spinal epidural haematoma: Report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 1994. 36: 456-9

7. Boyle EM, Maier RV, Salazar JD, Kovacich JC, O’Keefe G, Mann FA. Diagnosis of injuries after stab wounds to the back and flank. J Trauma. 1997. 42: 260-5

8. Ceruti S, Previsdomini M. Traumatic Brown-Séquard syndrome. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012. 5: 371-2

9. de Villiers JC, Grant AR. Stab wounds at the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery. 1985. 17: 930-6

10. Evans RJ, Richmond JM. An unusual death due to screwdriver impalement: A case report. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1996. 17: 70-2

11. Giner Pascual M, Alcácer VS, Pomares MV, Alberola MA. Brown-Séquard-plus syndrome after a stab injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011. 29: 353-7

12. Goyal RS, Goyal NK, Salunke P. Non-missile penetrating spinal injuries. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2009. 6: 81-4

13. Gray TL, Karagiannis A, Crompton JL, Selva D. Self-inflicted blindness and Brown-Séquard syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003. 23: 154-6

14. Jesmanas S, Norvainytė K, Gleiznienė R, Mačionis A. Retained glass fragment in the cervical spinal canal in a patient with acute transverse myelitis: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2018. 2018: 5129513

15. Jones FD, Woosley RE. Delayed myelopathy secondary to retained intraspinal metallic fragment. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1981. 55: 979-82

16. Jones FK, Babalola F, Eltayeb O, Teixeira A. Blowdart injury resulting in Brown-Séquard plus syndrome. Am Surg. 2005. 71: 1075-7

17. Karlins NL, Marmolya G, Snow N. Computed tomography for the evaluation of knife impalement injuries: Case report. J Trauma. 1992. 32: 667-8

18. Kim HS, Ko K. Penetrating trauma of the posterior fossa resulting in Vernet’s syndrome and internuclear ophthalmoplegia. J Trauma. 1996. 40: 647-9

19. Kocael H, Tafikapilio MÖ Bekar LA. Stab injury of the thoracic spinal cord: Case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2008. 18: 298-301

20. Komarowska M, Debek W, Wojnar JA, Hermanowicz A, Rogalski M. Brown-Séquard syndrome in a 11-year-old girl due to penetrating glass injury to the thoracic spine. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013. 23: S141-3

21. Kulkarni AV, Bhandari M, Stiver S, Reddy K. Delayed presentation of spinal stab wound: Case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2000. 18: 209-13

22. Lipschitz R, Block J. Stab wounds of the spinal cord. Lancet. 1962. 2: 169-72

23. Loncán LI, Sempere DF, Ajuria JE. Brown-Sequard syndrome caused by a Kirschner wire as a complication of clavicular osteosynthesis. Spinal Cord. 1998. 36: 797-9

24. McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K. Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007. 30: 215-24

25. Meena US, Kataria R, Sharma K, Sardana VR. Penetrating spinal cord injury with screwdriver in situ leading to Brown-Sequard syndrome. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016. 7: 324-7

26. Meltzer HS, Kim PJ, Ozgur BM, Levy ML. Vertebral body granuloma of the cervical region after pencil injury. Neurosurgery. 2004. 54: 1527-9

27. Moulton C, Crawford R, Swann IJ. Cutaneous leakage of cerebrospinal fluid following a stab wound to the back. Injury. 1994. 25: 118-9

28. Peacock WJ, Shrosbree RD, Key AG. A review of 450 stabwounds of the spinal cord. S Afr Med J. 1977. 51: 961-4

29. Prasad MK, Sinha AK, Bhadani UK, Chabra B, Rani K, Srivastava B. Management of difficult airway in penetrating cervical spine injury. Indian J Anaesth. 2010. 54: 59-61

30. Pribán V, Fiedler J. Spinal cord stab injury associated with modified Brown-Séquard syndrome symptoms-a case review and literature overview. Rozhl Chir. 2010. 89: 220-2

31. Rabiu TB, Aremu AA, Amao OA, Awoleke JO. Screw driver: An unusual cause of cervical spinal cord injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. 2011: bcr0620114309

32. Ritchie DA. Stab injury to the lumbar spine. Br J Hosp Med. 1993. 49: 574-5

33. Rodríguez-Quintero JH, Romero-Velez G, Pereira X, Kim PK. Traumatic Brown-Séquard syndrome: Modern reminder of a neurological injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2020. 13: e236131

34. Rubin G, Tallman D, Sagan L, Melgar M. An unusual stab wound of the cervical spinal cord: A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001. 26: 444-7

35. Schulz F, Colmant HJ, Trübner K. Penetrating spinal injury inflicted by screwdriver: Unusual morphological findings. J Clin Forensic Med. 1995. 2: 153-5

36. Singh P, Sarup S, Singh AP, Sharma AK. Non missile penetrating injury of spine with retained foreign body. Med J Armed Forces India. 1999. 55: 348-50

37. Smrkolj V, Balazic J, Princic J. Intracranial injuries by a screwdriver. Forensic Sci Int. 1995. 76: 211-6

38. Thakur RC, Khosla VK, Kak VK. Non-missile penetrating injuries of the spine. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991. 113: 144-8

39. Tutton MG, Chitnavis B, Stell IM. Screwdriver assaults and intracranial injuries. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000. 17: 225-6

40. Wallace DJ, Sy C, Peitz G, Grandhi R. Management of non-missile penetrating spinal injury. Neurosurg Rev. 2019. 42: 791-8

41. Wirz M, Zörner B, Rupp R, Dietz V. Outcome after incomplete spinal cord injury: Central cord versus Brown-Sequard syndrome. Spinal Cord. 2010. 48: 407-14

42. Wright RL. Intramedullary spinal cord abscess. Report of a case secondary to stab wound with good recovery following operation. J Neurosurg. 1965. 23: 208-10

43. Ye TW, Jia LS, Chen AM, Yuan W. Brown-Séquard syndrome due to penetrating injury by an iron fence point. Spinal Cord. 2010. 48: 582-4