- Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neurosciences, School of Medicine, Postgraduate Residency Program in Neurological Surgery, Neurosurgical Clinic, AOUP “Paolo Giaccone,” Palermo,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Highly Specialized Hospital of National Importance “Garibaldi,”

- Department of Neurosurgery, Cannizzaro Hospital, Catania, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Gianluca Scalia, Department of Neurosurgery, Highly Specialized Hospital of National Importance “Garibaldi,” Catania, Sicily, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_746_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Salvatore Marrone1, Roberta Costanzo1, Gianluca Scalia2, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Giovanni Federico Nicoletti2, Giuseppe Emmanuele Umana3. Burr hole on polyetheretherketone cranioplasty for the management of chronic subdural hematoma: A case report. 30-Sep-2022;13:454

How to cite this URL: Salvatore Marrone1, Roberta Costanzo1, Gianluca Scalia2, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino1, Giovanni Federico Nicoletti2, Giuseppe Emmanuele Umana3. Burr hole on polyetheretherketone cranioplasty for the management of chronic subdural hematoma: A case report. 30-Sep-2022;13:454. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11895/

Abstract

Background: In rare cases, chronic subdural hematoma can be a complication following cranioplasty implantation. Therefore, it can develop spontaneously or after a trauma in the underlying site of a duroplasty and represent, if compression of the brain structures, a life-threatening condition. In case of a patient with cranioplasty in polyetheretherketone (PEEK), performing a burr hole on prosthesis can represent, although unusual, an effective and safe technique for evacuation of the chronic subdural hematoma, avoiding the need to remove the prosthesis itself. Nevertheless, a rare and insidious prosthesis infection can occur, even after years.

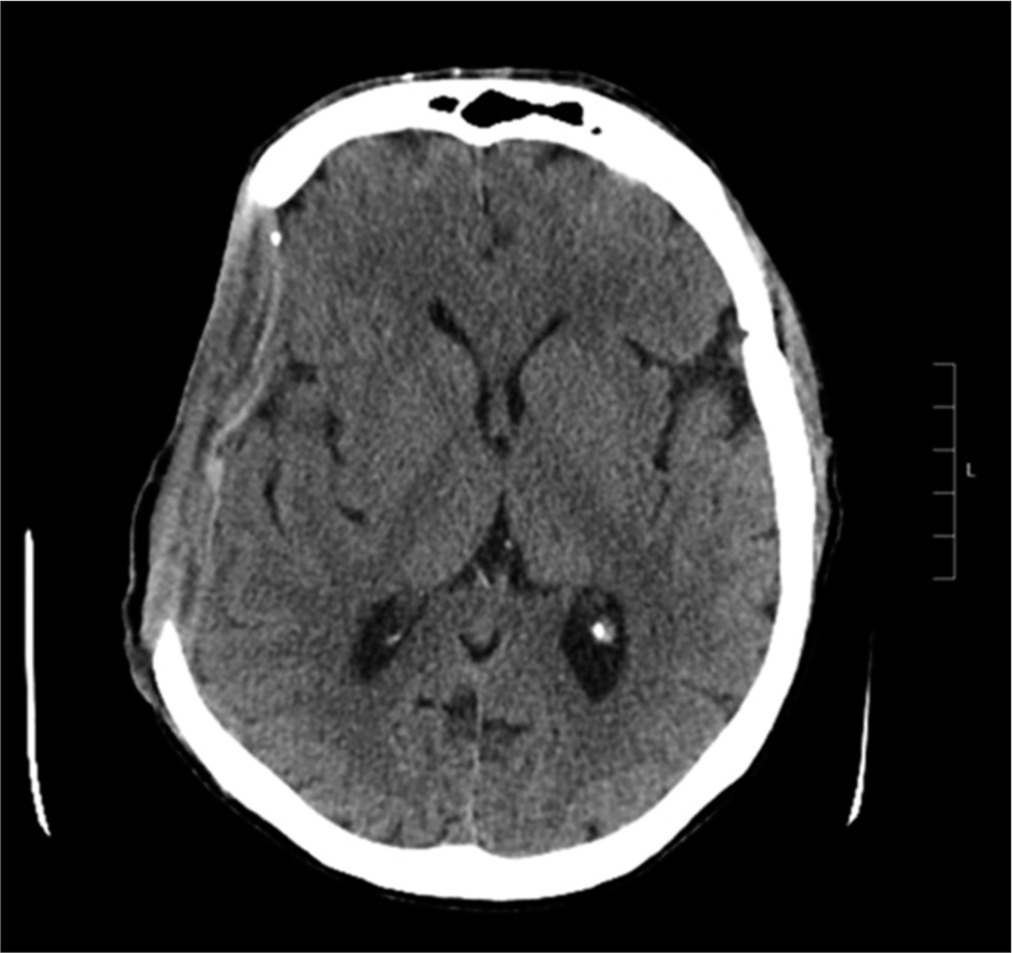

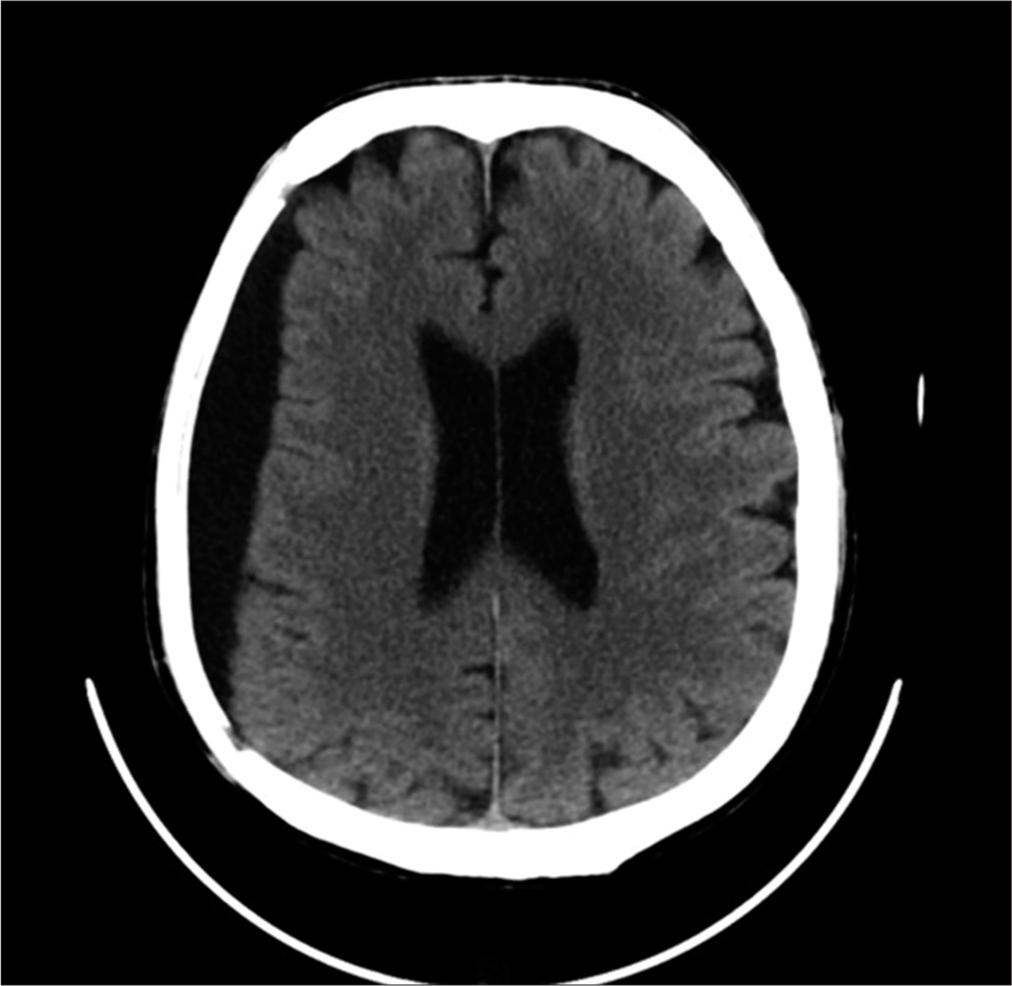

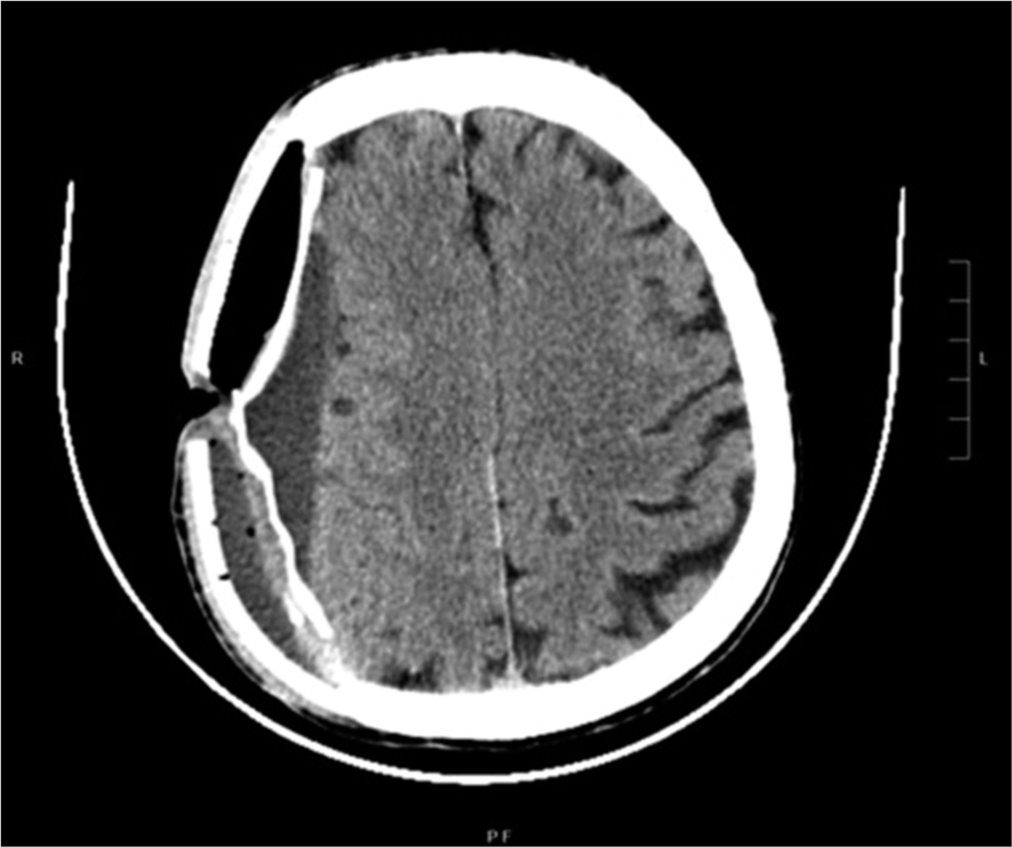

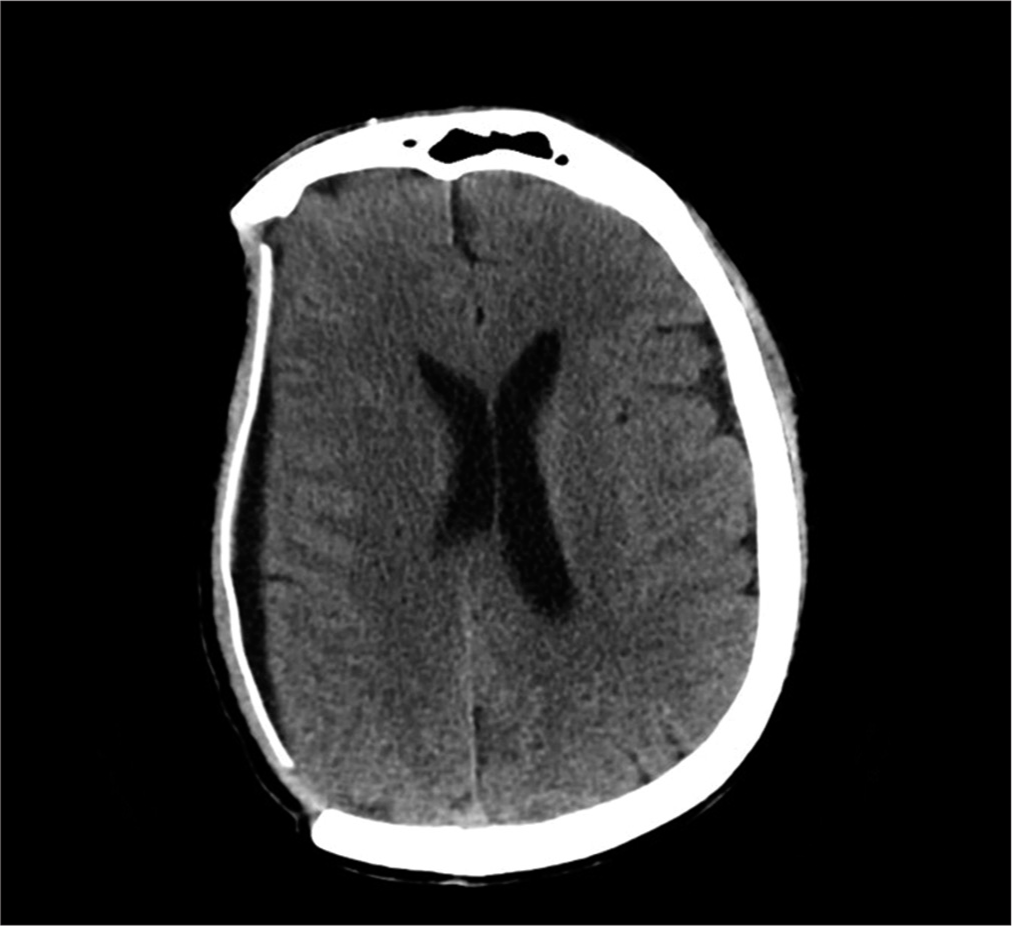

Case Description: A 54-year-old male patient, following severe traumatic brain injury, underwent a right hemispheric decompressive craniectomy associated to acute subdural hematoma evacuation and, subsequently, a PEEK cranioplasty implant with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE or Gore-Tex) duroplasty. About 10 years later, he experienced worsening headache with sensory alterations; therefore, he underwent a brain computed tomography scan documenting a right hemispheric chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH), expanding in subsequent radiological examinations. Because of symptoms’ worsening, he underwent cSDH evacuation through a burr hole centered on the parietal region of the PEEK prosthesis, associated with mini-reopening of duroplasty. Two years after the procedure, he went to the emergency department because of the appearance of a serum-purulent material drained from the surgical site. He underwent cranioplasty removal and then started a targeted therapy to treat a triple surgical site infection, often unpredictable and totally accidental.

Conclusion: Based on the literature evidence, performing a burr hole on a cranial prosthesis in bone-like material such as PEEK represents a surgical procedure never performed before and in our opinion could, in selected cases, guarantee the cSDH evacuation and the treatment of intracranial hypertension, avoiding the cranioplasty removal, although there is a risk of even late surgical site infection.

Keywords: Burr hole, Chronic subdural hematoma, Cranioplasty, Gore-Tex, PEEK, Surgical site infection

INTRODUCTION

In rare cases, chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) can be a complication following cranioplasty implantation.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

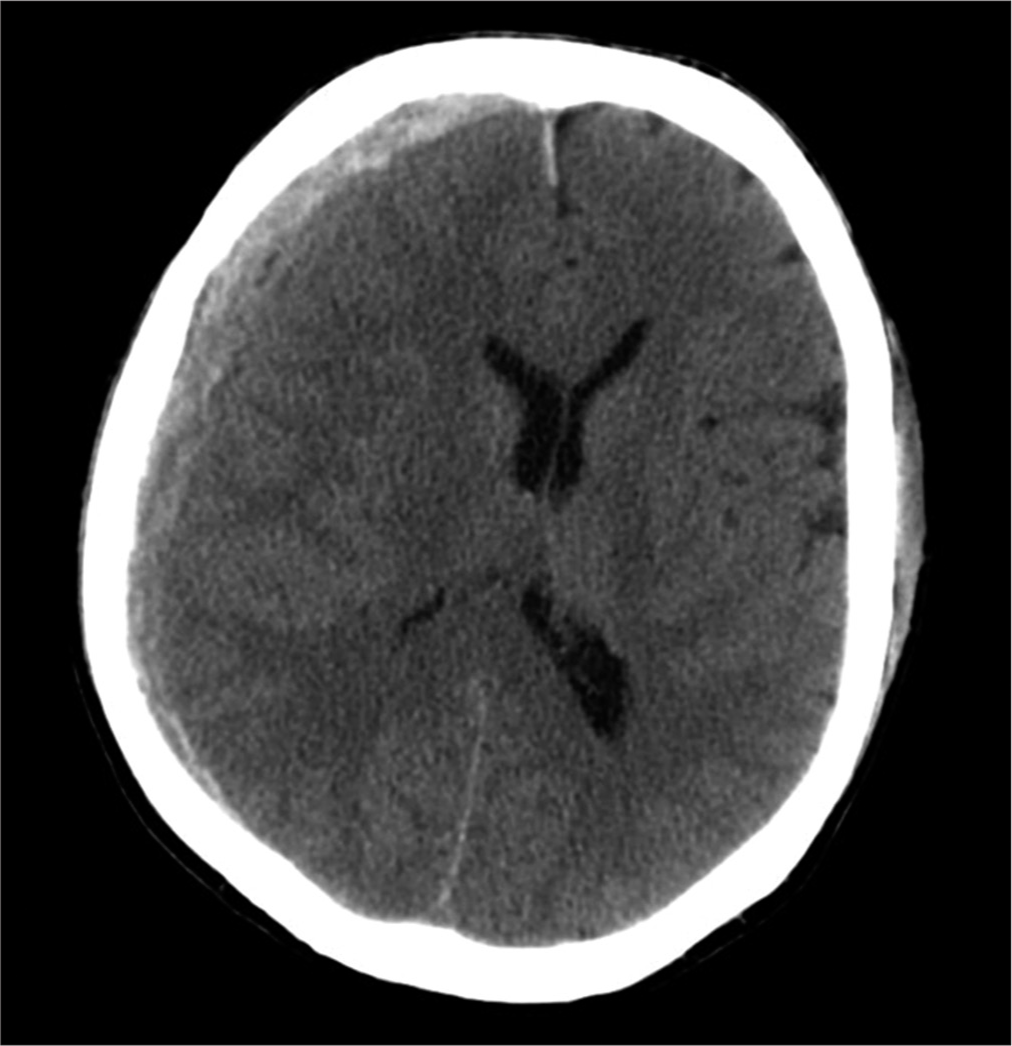

A 54-year-old male patient, following severe head trauma associated to acute subdural hematoma [

DISCUSSION

cSDH represents a rare complication following cranioplasty implantation.[

Messing-Jünger et al. showed 119 patients requiring duroplasty after surgery, demonstrating Gore-Tex safety and manageability thanks to a good resistance against engraftment and colonization by pathogens.[

Sheen et al. demonstrated that this bacterium can invade and destroy the blood–brain barrier – endotheliocytes migrating from the bloodstream to the brain parenchyma or meninges.[

As far as we know, this infection was the primum movens causing the colonization from other microorganisms. In fact, intraoperatively, a congested tissue was found because of the release of numerous pro-inflammatory factors[

The second bacterium involved in the surgical site infection was S. haemolyticus. This is a methicillin-resistant coccus and represents the main opportunistic pathogen related to infections in head trauma or in patients who underwent a neurosurgical procedure. This bacterium can cause postoperative meningitis in adult patients, as well as infections of many implantable devices.[

Patient’s manual work and related repeated traumatism, the precarious hygienic conditions as well as a poor skin trophism could have influenced the delayed onset of the infection after burr hole procedure, despite the regular antibiotic prophylaxis.

CONCLUSION

Based on the literature evidence, performing a burr hole on a cranial prosthesis in bone-like material such as PEEK and the duroplasty incision represents a surgical procedure never performed before and in our opinion could, in selected cases, guarantee the cSDH evacuation avoiding the cranioplasty removal. Nevertheless, delayed brain surgical site infections due to three different microorganisms represent a rare event and even more rare is the coinfection of heterologous materials used for bone reconstruction and duroplasty. There is still no consensus on reliable risk factors for delayed graft infections as they are often unpredictable and totally accidental, despite a regular antibiotic prophylaxis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Azimi T, Mirzadeh M, Sabour S, Nasser A, Fallah F, Pourmand MR. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) meningitis: A narrative review of the literature from 2000 to 2020. New Microbes New Infect. 2020. 37: 100755

2. Chang WN, Lu CH, Huang CR, Chuang YC. Mixed infection in adult bacterial meningitis. Infection. 2000. 28: 8-12

3. Chaturvedi J, Botta R, Prabhuraj AR, Shukla D, Bhat DI, Devi BI. Complications of cranioplasty after decompressive craniectomy for traumatic brain injury. Br J Neurosurg. 2016. 30: 264-8

4. Dhanumalayan E, Joshi GM. Performance properties and applications of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-a review. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2018. 1: 247-68

5. Hu Y, Li X, Zhao R, Zhang K. Conservative treatment for delayed infection after cranioplasty with titanium alloy. J Craniofac Surg. 2018. 29: 1258-60

6. Ku SC, Hsueh PR, Yang PC, Luh KT. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of bacteremia caused by Acinetobacter lwoffii. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000. 19: 501-5

7. McNicholas S, Talento AF, O’Gorman J, Hannan MM, Lynch M, Greene CM. Cytokine responses to Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection differ between patient cohorts that have different clinical courses of infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2014. 14: 580

8. Messing-Jünger AM, Ibáñez J, Calbucci F, Choux M, Lena G, Mohsenipour I. Effectiveness and handling characteristics of a three-layer polymer dura substitute: A prospective multicenter clinical study. J Neurosurg. 2006. 105: 853-8

9. Nair N, Biswas R, Götz F, Biswas L. Impact of Staphylococcus aureus on pathogenesis in polymicrobial infections. Infect Immun. 2014. 82: 2162-9

10. Saliba WR, Goldstein LH, Raz R, Mader R, Colodner R, Elias MS. Subacute necrotizing fasciitis caused by gas-producing Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Di. 2003. 22: 612-4

11. Sheen TR, Ebrahimi CM, Hiemstra IH, Barlow SB, Peschel A, Doran KS. Penetration of the blood-brain barrier by Staphylococcus aureus Contribution of membrane-anchored lipoteichoic acid. J Mol Med (Berl). 2010. 88: 633-9

12. Tian R, Hao S, Hou Z, Gao Z, Liu B. The characteristics of post-neurosurgical bacterial meningitis in elective neurosurgery in 2012: A single institute study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015. 139: 41-5