- Department of Neurological Surgery, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Urayasu, Japan,

- Department of Pathology, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Urayasu, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Satoshi Tsutsumi, Department of Neurological Surgery, Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital, Urayasu, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_558_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Hiroki Sugiyama1, Satoshi Tsutsumi1, Akane Hashizume2, Kiyotaka Kuroda1, Natsuki Sugiyama1, Hideaki Ueno1, Hisato Ishii1. Calvarial Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult presenting rapid growth. 05-Aug-2022;13:347

How to cite this URL: Hiroki Sugiyama1, Satoshi Tsutsumi1, Akane Hashizume2, Kiyotaka Kuroda1, Natsuki Sugiyama1, Hideaki Ueno1, Hisato Ishii1. Calvarial Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult presenting rapid growth. 05-Aug-2022;13:347. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11757/

Abstract

Background: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) arising in the skull is rare in adulthood.

Case Description: A 58-year-old woman experienced a durable headache. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at presentation showed no abnormalities; however, MRI and computed tomography (CT) performed 6 weeks later revealed the emergence of a well-demarcated, heterogeneously enhancing calvarial tumor accompanied by irregular-shaped bone erosion. On MRI, the temporalis muscle and subcutaneous tissue adjacent to the tumor were extensively swollen and enhanced. The patient underwent en bloc resection. The microscopic appearance of the tumor was consistent with that of LCH. Postoperative systemic 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT did not detect any abnormal accumulation.

Conclusion: LCH may develop within a short period. It should be considered as a differential diagnosis when a rapidly growing calvarial tumor is encountered, even when the patient is an adult. Prompt histological verification is recommended in such cases.

Keywords: Adult, Calvarium, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Rapid growth

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is thought to be a proliferative disorder of bone marrow-derived immature cells, presenting with diverse clinical manifestations, that commonly affect skeletal bones, skin, lymph nodes, and lungs.[

Here, we present an isolated calvarial LCH in an adult patient that developed within a short period of time.

CASE PRESENTATION

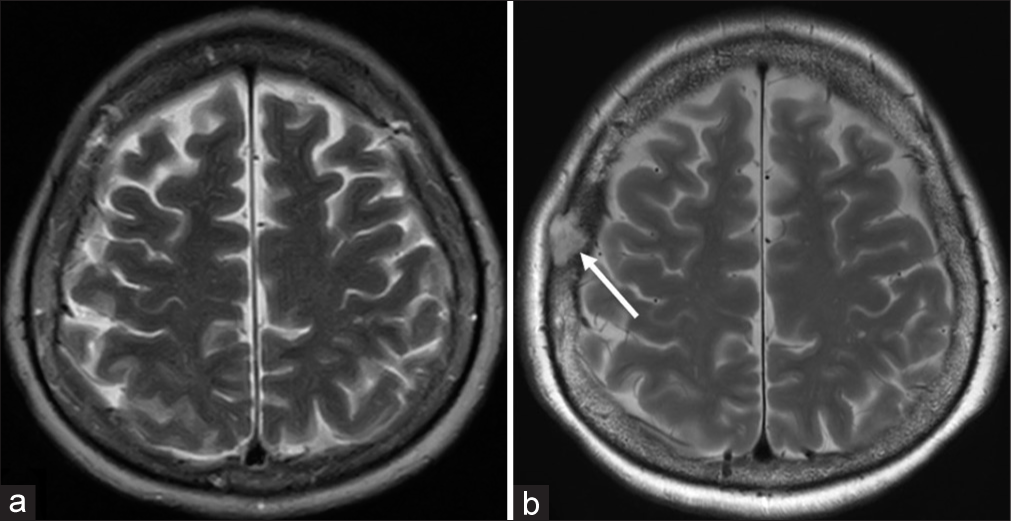

A 58-year-old, previously healthy woman, presented to a local physician with a headache. Her medical history was unremarkable, and she had not experienced a previous craniotomy or head injury. Headache was neither distinctive nor localized to a specific cranial region. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the time did not reveal any abnormal findings in the intracranial cavity, skull, or scalp [

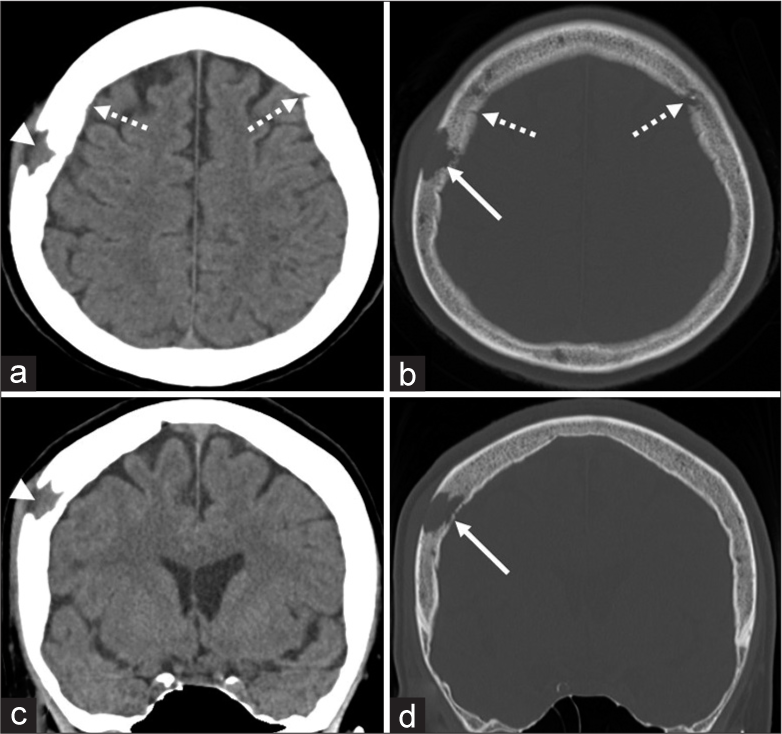

Figure 2:

Axial (a) and coronal (c) computed tomography scans and their corresponding bone target images (b and d) showing an isodense mass in the right parietal bone (a and c, arrowhead) accompanied by irregularly shaped bone erosion mainly involving the diploe and outer table (b and d, arrow). The inner table is partially erosive (d, arrow). Dashed arrow: coronal suture.

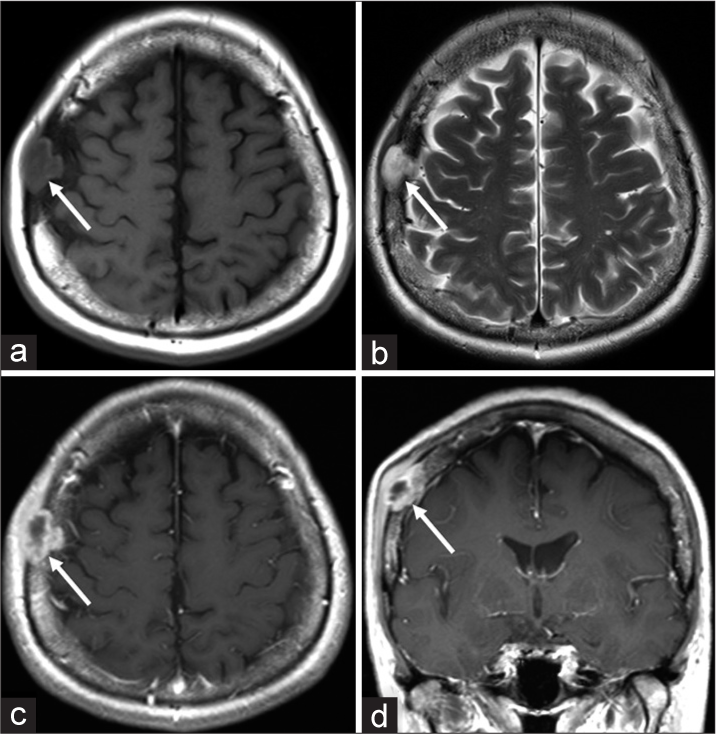

Figure 3:

Axial T1- (a) and T2- (b) weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing a calvarial tumor presenting iso/low intensity on T1- and high intensity on T2-weighted images, and well demarcated from the surrounding tissue (arrow). Post contrast axial (c) and coronal (d) T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing heterogeneous enhancement of the tumor with the inner part adjacent to the dura mater (arrow). Note that the temporalis muscle and subcutaneous tissue adjacent to the tumor are extensively swollen and enhanced compared to those on the contralateral side.

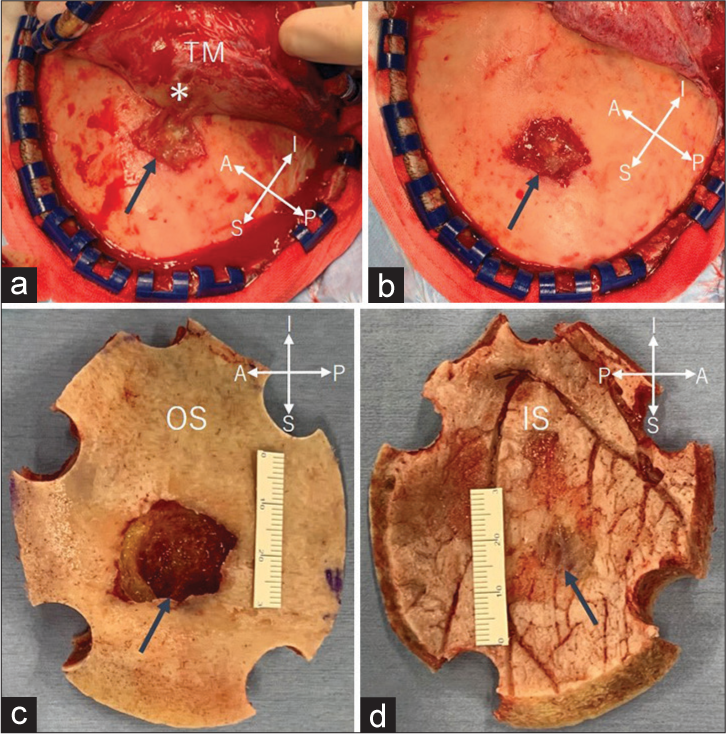

Figure 4:

(a-d) Intraoperative photos. (a and b) Reflection of the scalp flap showing a whitish tumor protruding through the completely eroded outer table (arrow). The tumor is partially adhered to the inner surface of the temporalis muscle (a, asterisk). (c) En bloc tumor resection has been achieved with surrounding bone. (d) Fine defects are found in the inner table adjacent to the tumor (arrow). A: Anterior, I: inferior, IS: inner surface of the skull, OS: outer surface of the skull, P: posterior, S: superior, TM: temporalis muscle, Arrow in (c): bone defect, 25 × 20 mm in diameter at the outer surface of skull; Asterisk: tumor tissue adhered to the temporalis muscle fibers.

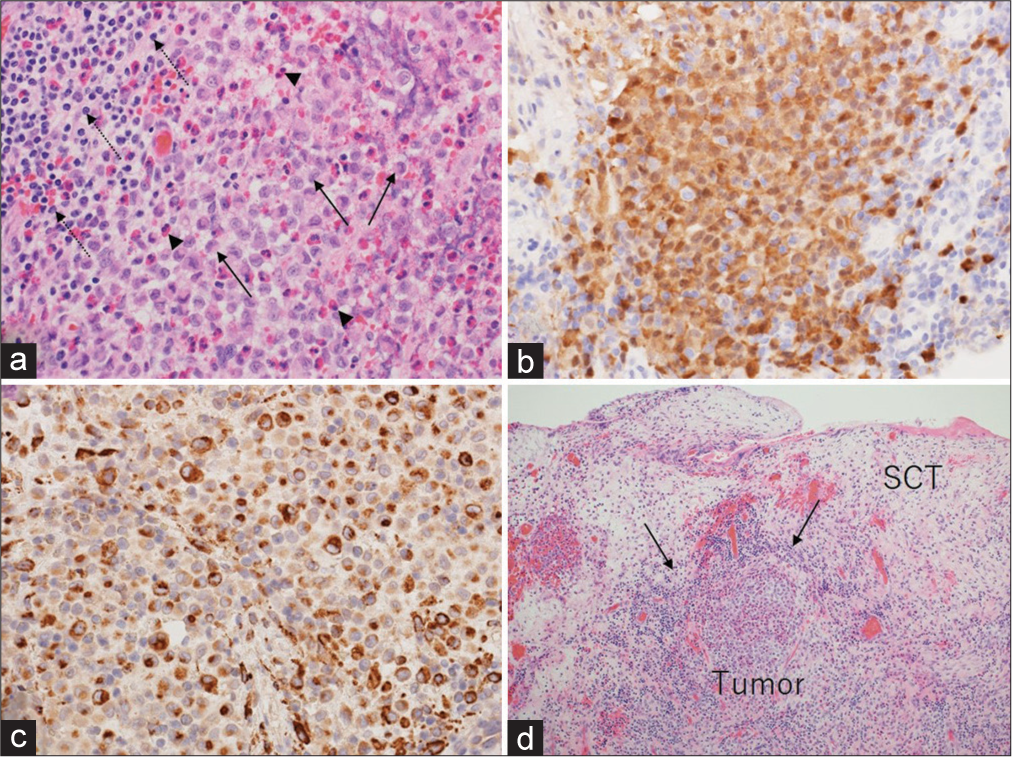

Figure 5:

(a) Photomicrograph of the resected specimen showing proliferation of neoplastic cells with cleaved nuclei (arrows) accompanied by infiltration of the lymphocytes (dashed arrows) and eosinophils (arrowheads). Immunohistochemical examination showing positive staining for the S100 protein (b) and CD68 (c). Tumor invasion of the subcutaneous tissue is observed (d, arrows). SCT: Subcutaneous tissue. (a and d): hematoxylin and eosin stain. (a): × 200, (d): × 40, and (b and c): × 200.

DISCUSSION

In the present case, rapid growth of the calvarial LCH was detected for 6 weeks. During this period, the LCH formed an osteolytic lesion measuring 25 × 20 mm in diameter. Osteolytic calvarial lesions are documented to be an infrequent entity. In a previous study involving 10 children younger than 15 years and 26 adult patients, the most common pathological diagnoses were metastasis and LCH (25.0%), followed by intraosseous hemangioma (13.9%).[

The rapid growth of the present LCH and its lymphocytic infiltration suggests that the inflammatory reaction might be associated with the local pain. However, the correlation between the patient’s headache that had persisted before radiological emergence of the LCH and its pathology is unknown.

In this case, the temporalis muscle and subcutaneous tissue adjacent to the tumor appeared thick and were extensively enhanced on the presurgical MRI. In contrast, intraoperative findings showed that the outer surface of the tumor was mostly well demarcated from the surrounding tissue. Microscopically, only a subtle tumor invasion was observed in the adjacent subcutaneous tissue. Therefore, on MRI, inflammatory mechanisms were thought to be predominantly associated with the appearance of the temporalis muscle.

The patient was diagnosed with monostotic LCH. In general, such LCH is anticipated to have a good prognosis without the need for systemic therapy after successful initial treatment.[

CONCLUSION

LCH may develop within a short period. It should be considered as a differential diagnosis when a rapidly growing calvarial tumor is encountered, even when the patient is an adult. Prompt histological verification is recommended in such cases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. AbdullGaffar B, Awadhi F. Oral manifestations of langerhans cell histiocytosis with unusual histomorphologic features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2020. 47: 151536

2. Chiaravalli S, Ferrari A, Bergamaschi L, Puma N, Gattuso G, Sironi G. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: A retrospective, single-center case series. Ann Hematol. 2022. 101: 265-72

3. Chiong C, Jayachandra S, Eslick GD, Al-Khawaja D, Casikar V. A rare case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the skull in an adult: A systematic review. Rare Tumors. 2013. 5: e38

4. Demir MK, Yapıcıer O, Hasanov T, Kilic D, Kilic T. A rapidly expanding calvarial Langerhans cell histiocytosis with low Ki-67 in an adult: A challenging diagnosis on magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroradiol J. 2018. 31: 390-4

5. Hong B, Hermann EJ, Klein R, Krauss JK, Nakamura M. Surgical resection of osteolytic calvarial lesions: Clinicopathological features. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010. 112: 865-9

6. Howarth DM, Gilchrist GS, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Edmonson JH, Schomberg PJ. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Diagnosis, natural history, management, and outcome. Cancer. 1999. 85: 2278-90

7. Ishibashi M, Izumi E. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient presenting with eruptions on the scalp and trunk accompanied by lytic lesions on the skull. Int J Dermatol. 2016. 55: e408-10

8. Kim SS, Hong SA, Shin HC, Hwang JA, Jou SS, Choi SY. Adult Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis with multisystem involvement: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018. 97: e13366

9. Kono M, Inomoto C, Horiguchi T, Sugiyama I, Nakamura N, Saito R. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis diagnosed by biopsy of the skull tumor generated after craniotomy. NMC Case Rep. 2021. 8: 101-5

10. Maia RC, de Rezende LM, Robaina M, Apa A, Klumb CE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: Differences and similarities in long-term outcome of paediatric and adult patients at a single institutional centre. Hematology. 2015. 20: 83-92

11. Makras P, Papadogias D, Samara C, Zetos A, Kaltsas G, Piaditis G. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis in an adult patient manifested as recurrent skull lesions and Diabetes Insipidus. Hormones (Athens). 2004. 3: 59-64

12. Modest MC, Garcia JJ, Arndt CS, Carlson ML. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the temporal bone: A review of 29 cases at a single center. Laryngoscope. 2016. 126: 1899-904

13. Moteki Y, Yamada M, Shimizu A, Suzuki A, Suzuki N, Kobayashi T. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the skull in a burr hole site covered with hydroxyapatite material. World Neurosurg. 2019. 122: 632-7

14. Rosso DA, Roy A, Zelazko M, Braier JL. Prognostic value of soluble interleukin 2 receptor levels in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2002. 117: 54-8

15. Schultz C, Klouche M, Friedrichsdorf S, Richter N, Kroehnert B, Bucsky P. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in children: Does soluble interleukin-2-receptor correlate with both disease extent and activity?. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998. 31: 61-5

16. Schwartz TR, Elliott LA, Fenley H, Ramdas J, Greene JS. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the head and neck: Experience at a rural tertiary referral center. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022. p. 34894221098466

17. Zhang XH, Zhang J, Chen ZH, Sai K, Chen YS, Wang J. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of skull: A retrospective study of 18 cases. Ann Palliat Med. 2017. 6: 159-64