- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Raj Thakrar, M.D., M.S. Department of Neurosurgery, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1034_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Raj Thakrar1, Bruce Tranmer1, Paul Penar1. Chiari malformation and spinal interdural cyst: A proposed association and review of the literature. 30-Dec-2021;12:626

How to cite this URL: Raj Thakrar1, Bruce Tranmer1, Paul Penar1. Chiari malformation and spinal interdural cyst: A proposed association and review of the literature. 30-Dec-2021;12:626. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11314/

Abstract

Background: Interdural cysts are rare meningeal cysts with an unclear etiology. They are often mistaken for other mass lesions, including arachnoid cysts and tumors. Correctly identifying and classifying these cysts, as well as how they have formed in individual patients, are crucial to providing effective treatment options for patients.

Case Description: We report a case of a patient with shunted idiopathic intracranial hypertension who developed a symptomatic Chiari malformation and was subsequently discovered to have a spinal interdural cyst. The Chiari malformation was likely due to intracranial hypotension secondary to lumbar cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion. Once the shunt was removed, a spinal interdural cyst became clinically and radiographically evident, and the Chiari resolved, suggesting that both entities were effects of shared CSF flow dynamics.

Conclusion: This cyst likely originated due to the trauma from remote repeated lumbar punctures and lumboperitoneal shunt placement, allowing CSF to enter the interdural space after the catheter was removed.

Keywords: Chiari, Cyst, Interdural, Meningeal, Shunt

INTRODUCTION

Interdural cysts are rare entities within the classification of meningeal cysts for which the etiology is often unclear. They are often mistaken for other mass lesions, including arachnoid cysts and tumors. A new classification schema has been introduced, and it is imperative to correctly identify and classify these cysts to provide effective treatment options for patients. Interdural cysts can exert mass effect on the adjacent neural elements, and as they are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), it is hypothesized that they contribute to the overall flow dynamics of the CSF space.

CASE REPORT

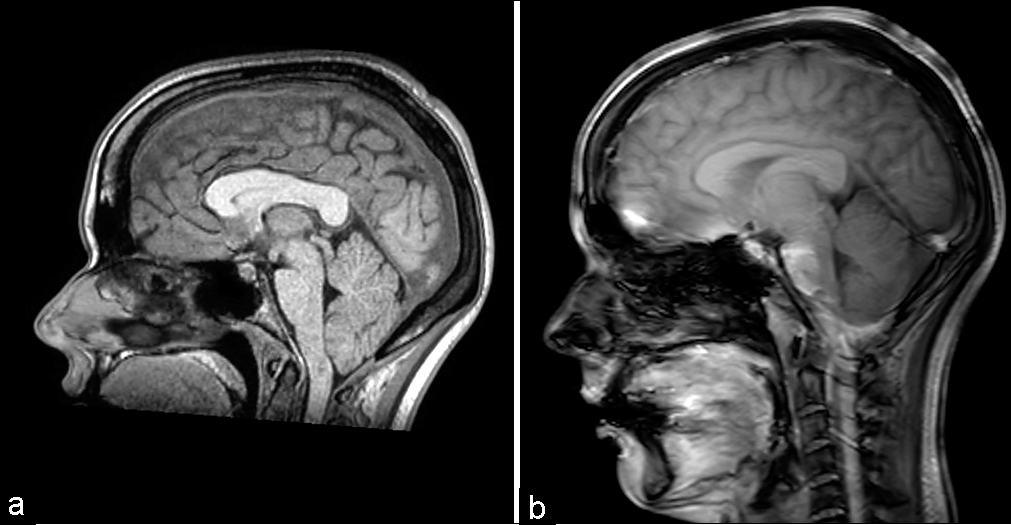

We present a case of a 30-year-old woman with a history of multiple inpatient admissions and outpatient visits for headaches due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension status – postlumboperitoneal (LP) shunt placement with a programmable valve 5 years before at another institution. She presented with new nonpositional tussive headaches, without any deficits on physical examination. Her LP shunt valve (Strata II) was confirmed to be set at 2.0, stable from 3 months before, when the resistance was increased from 1.0. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, demonstrating a Chiari I malformation [

Computed tomography (CT) and MRI studies

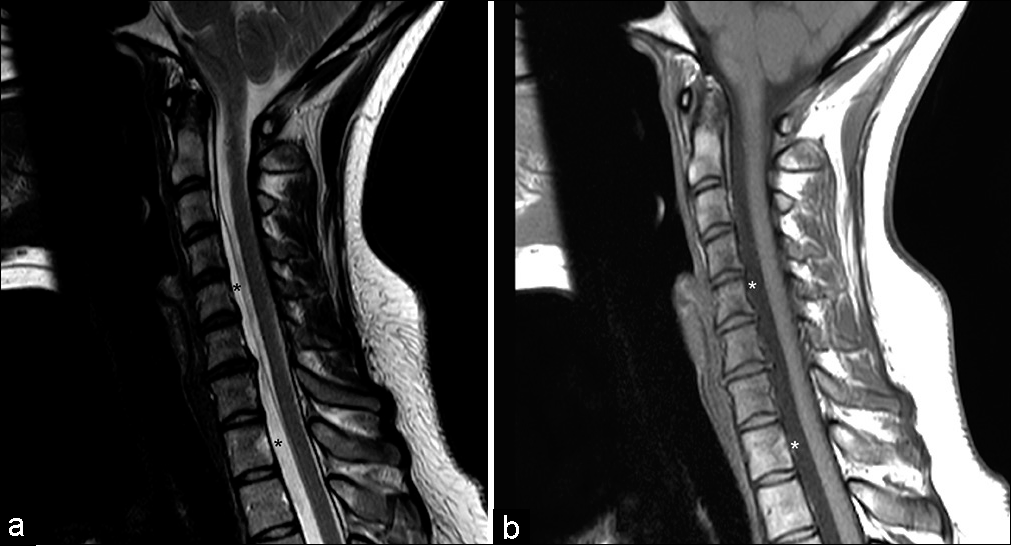

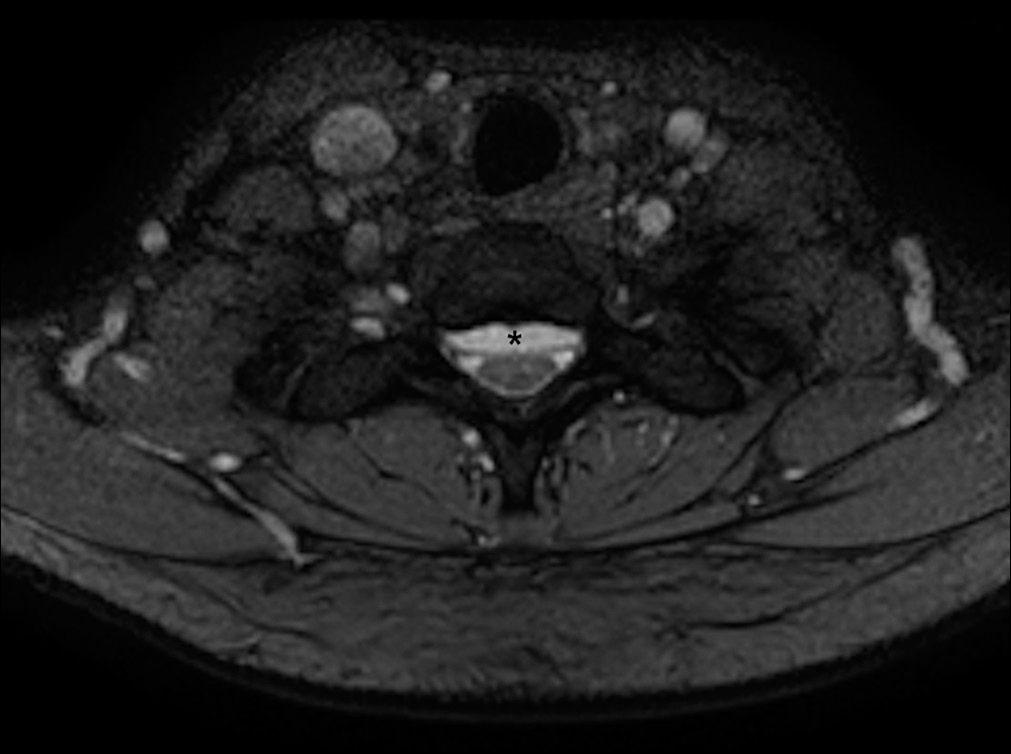

CT of the head and shunt series showed baseline small ventricle caliber and no shunt system disconnection, respectively. Her shunt remained at a moderate resistance (Certas Plus set at 5). Cervical MRI revealed resolution of the Chiari malformation. However, there was now an intradural extramedullary lesion ventral to the spinal cord starting at C3 and extending to L3. The lesion was hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging [

Figure 2:

(a) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI cervical spine demonstrating high-intensity cystic cavity ventral to the spinal cord, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid, signified by black asterisks. (b) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI cervical spine demonstrating low-intensity cystic cavity ventral to the spinal cord, isointense to cerebrospinal fluid, signified by white asterisks.

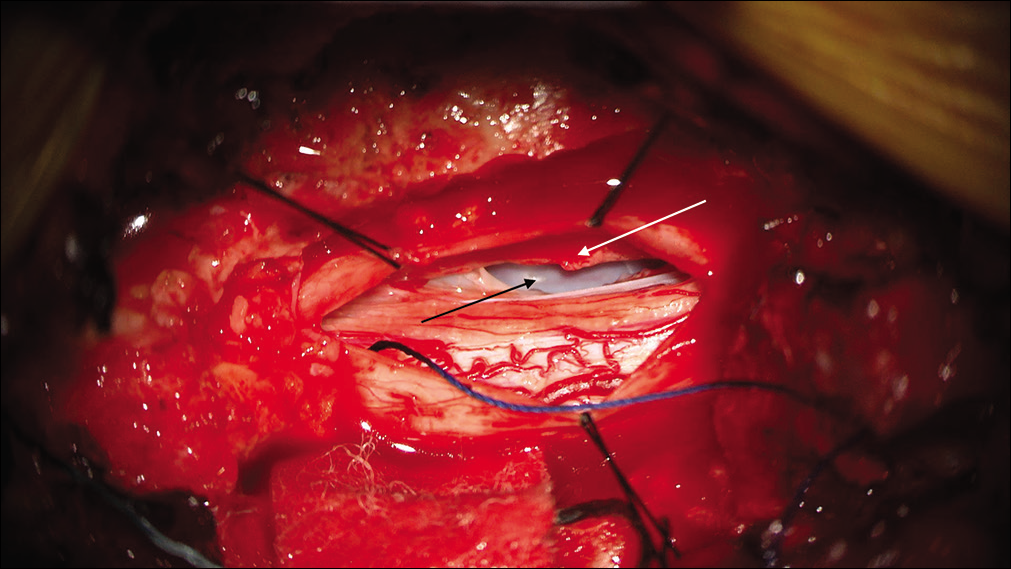

Surgery

Given her continued sensory symptoms, a decision was made to fenestrate the interdural cyst in the lower thoracic region.

A T11 laminectomy was performed, and the dura was opened just left of midline. After the arachnoid adhesions were released, a fluctuant dural surface was encountered anteriorly in the canal, with no other visible abnormality. The inner layer of the dura was incised and revealed a fluid-filled cavity, bounded by dura. This confirmed the presence of an interdural cyst [

Postoperatively, the patient reported improvement in bilateral upper extremity tingling. At her 6-week follow-up appointment, she reported resolution of her paresthesias.

Head CT also demonstrated continued resolution of her Chiari malformation.

DISCUSSION

In 1988, based on a series of 22 cases, Nabors et al. attempted to describe an updated classification of spinal meningeal cysts, defined as diverticula filled with CSF, as extradural or intradural.[

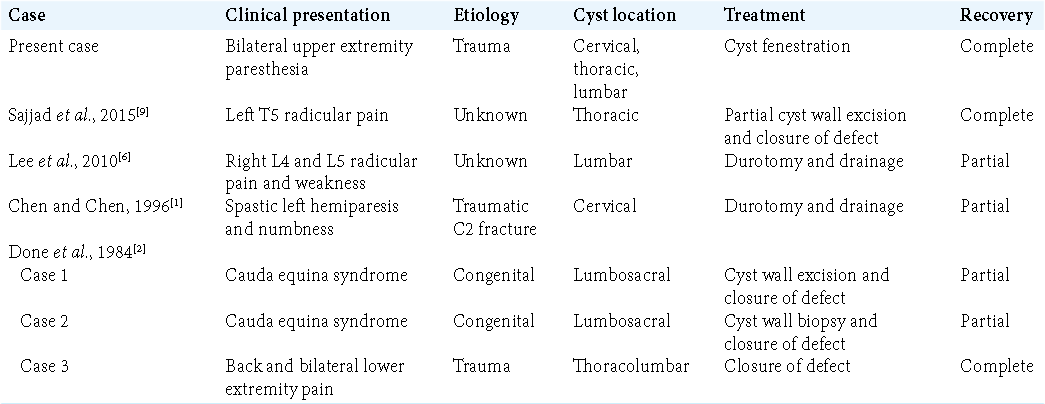

Since the Nabors classification, there have been a number of case reports describing interdural cysts. Done et al. outlined a series of three patients who presented with cauda equina syndrome (two patients) and severe back and bilateral leg pain (one patient) and imaging findings of lumbosacral interdural cysts.[

Due to an ever-growing recognition of this entity, new dural cyst classification systems have been proposed.[

A unique presentation

The case described here is unique given the discovery of a new Chiari malformation at initial presentation and subsequent diagnosis of the interdural cyst, implying possible relationship between the two entities. Before the patient’s initial presentation, her LP shunt (Strata II valve) had been confirmed to be functioning. The setting was increased from 1.0 to 2.0 3 months before her initial presentation, thereby decreasing flow. Despite this, her imaging findings of Chiari malformation and clinical symptoms were consistent with intracranial hypotension. There are well-documented reports of intracranial hypotension resulting in an acquired Chiari I malformation.[

Due to alterations of CSF flow dynamics following removal of the LP shunt with concurrent placement of a VP shunt and resolution of the Chiari malformation, we propose that a defect in the dura worsened, forming the interdural cyst. Subsequent expansion of this cyst exerted mass effect on her cervical spinal cord and resulted in her presenting with bilateral upper extremity paresthesia. We believe that the mechanism for a dural defect in this patient was trauma, whether from multiple lumbar punctures before shunting or placement of the lumbar shunt catheter itself.

CONCLUSION

We report an unusual case of acquired Chiari malformation in a patient with an LP shunt who then presented with an extensive, and symptomatic, spinal interdural cyst after removal of the LP shunt, likely due to trauma from remote repeated lumbar punctures and LP shunt placement, allowing CSF to enter the interdural space after the catheter was removed; after fenestration of the cyst, the patient reported resolution in symptoms.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Chen HJ, Chen L. Traumatic interdural arachnoid cyst in the upper cervical spine. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996. 85: 351-3

2. Done SL, Hayman LA, New PF, Davis KR, Chapman PH. Interdural cyst of the lumbosacral region. Neurosurgery. 1984. 14: 287-94

3. Hentati A, Badri M, Bahri K, Zammel I. Acquired Chiari I malformation due to lumboperitoneal shunt: A case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2019. 10: 78

4. Hoffman EP, Garner JT, Johnson D, Shelden CH. Traumatic arachnoidal diverticulum associated with paraplegia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1973. 38: 81-5

5. Klekamp J. A new classification for pathologies of spinal meninges, Part 1: Dural cysts, dissections, and ectasias. Neurosurgery. 2017. 81: 29-44

6. Lee JH, Jung TG, Kim HS, Jang JS, Lee SH. Symptomatic isolated lumbar interdural arachnoid cyst. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010. 50: 1035-8

7. Mukherjee S, Kalra N, Warren D, Sivakumar G, Goodden JR, Tyagi AK. Chiari I malformation and altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics-the highs and the lows. Childs Nerv Syst. 2019. 35: 1711-7

8. Nabors MW, Pait TG, Byrd EB, Karim NO, Davis DO, Kobrine AI. Updated assessment and current classification of spinal meningeal cysts. J Neurosurg. 1988. 68: 366-77

9. Sajjad J, Yousaf I, Bermingham N, Kaar G. Interdural spinal cyst: A rare clinical entity. World Neurosurg. 2016. 88: 688.e9-12

10. Taguchi Y, Suzuki R, Okada M, Sekino H. Spinal arachnoid cyst developing after surgical treatment of a ruptured vertebral artery aneurysm: A possible complication of topical use of fibrin glue. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1996. 84: 526-9