- Department of Neurosurgery, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan

- Department of Neuropathology, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Takafumi Shimogawa, Department of Neurosurgery, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_133_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical termsHow to cite this article: Kohei Irie1, Takafumi Shimogawa1, Nobutaka Mukae1, Daisuke Kuga1, Toru Iwaki2, Masahiro Mizoguchi1, Koji Yoshimoto1. Combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and cyst-peritoneal shunt in an infant with glioependymal cyst. 25-Mar-2022;13:102

How to cite this URL: Kohei Irie1, Takafumi Shimogawa1, Nobutaka Mukae1, Daisuke Kuga1, Toru Iwaki2, Masahiro Mizoguchi1, Koji Yoshimoto1. Combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and cyst-peritoneal shunt in an infant with glioependymal cyst. 25-Mar-2022;13:102. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11488/

Abstract

Background: Glioependymal cysts (GECs) are rare, benign congenital intracranial cysts that account for 1% of all intracranial cysts. Surgical interventions are required for patients with symptomatic GECs. However, the optimal treatment remains controversial, especially in infants. Here, we report a male infant case of GECs that successfully underwent minimally invasive combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and cyst-peritoneal (CP) shunt.

Case Description: The boy was delivered transvaginally at 38 weeks and 6 days of gestation with no neurological deficits. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at birth revealed multiple cysts with smooth and rounded borders and a non-enhancing wall in the right parieto-occipital region. The size of the cyst had increased rapidly compared to that of the prenatal MRI, which was performed at 37 weeks and 2 days. On the day of birth, Ommaya cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reservoir was placed into the largest outer cyst. The patient underwent intermittent CSF drainage; however, he experienced occasional vomiting. At 2 months, he underwent combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and CP shunt through a small hole. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and there was no recurrence of the cyst. The pathological diagnosis was GEC.

Conclusion: Combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and CP shunt are a minimally invasive and effective treatment for infants with GECs.

Keywords: Cyst-peritoneal shunt, Ependymal cyst, Glioependymal cyst, Neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration

INTRODUCTION

Glioependymal cysts (GECs) are rare and benign congenital intracranial cysts that account for 1% of all intracranial cysts.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

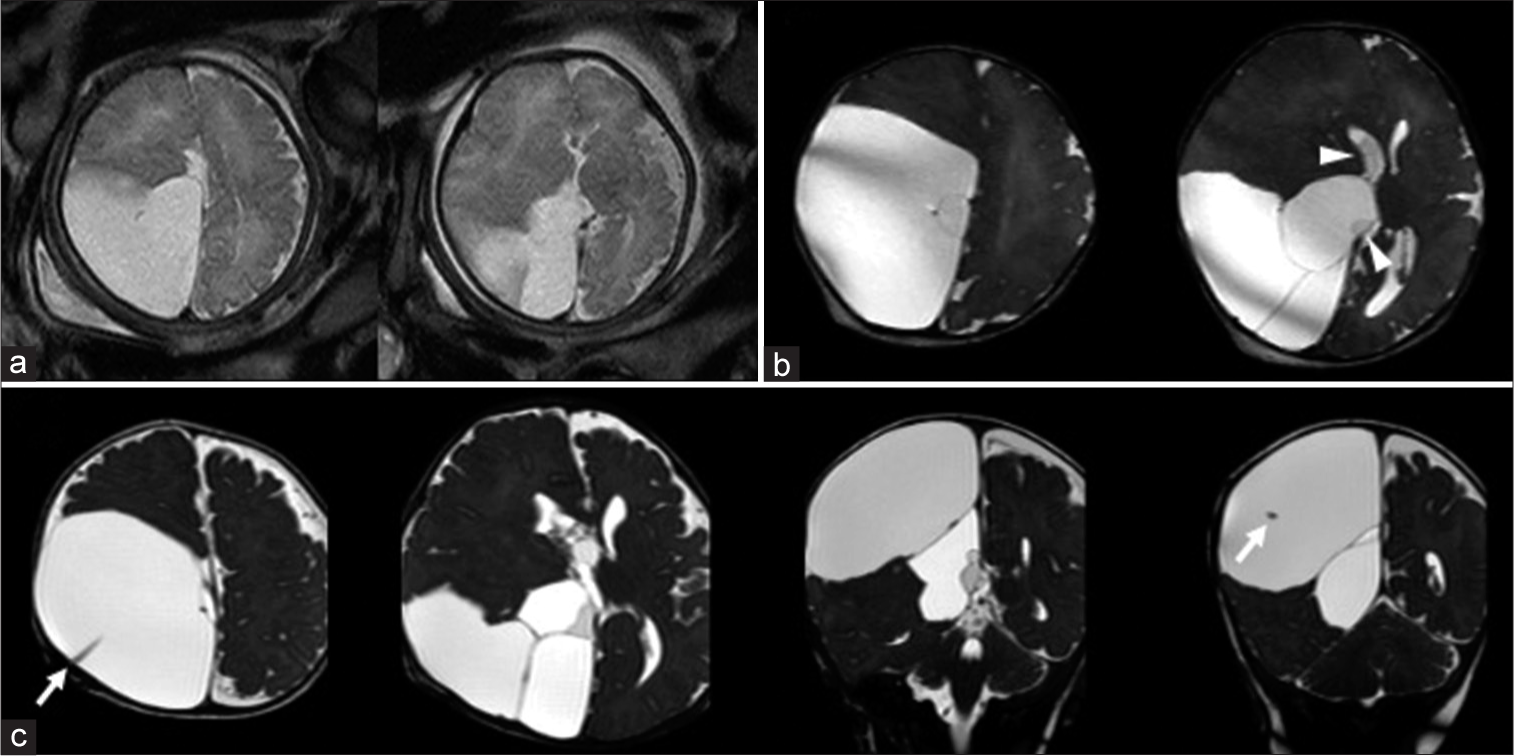

A 33-year-old, healthy, gravida 3, and para 2 woman underwent routine examination by transabdominal ultrasound at 35 weeks and 5 days during a seemingly uneventful pregnancy. Ultrasonography revealed an intracranial cyst in the baby. Prenatal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo sequence (HASTE) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at 37 weeks and 2 days showed a large cyst measuring 70 mm in maximal length in the right parieto-occipital region [

Figure 1:

(a) Prenatal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo sequence (HASTE) image at 37 weeks and 2 days of gestation showing a huge cyst in the right parieto-occipital region. (b) 3D-heavily T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (3D-hT2WI) at birth (at 38 weeks and 6 days) revealed multiple cysts with various intensities in the right parieto-occipital region (white arrowheads). These cysts were not connected to the right lateral ventricle. The posterior part of the corpus callosum was partially absent. (c) Axial and coronal 3D-hT2WI at 2 months revealed that the cyst remained large even after intermittent drainage. The Ommaya reservoir is placed in the largest cyst (white arrows).

A boy weighing 3204 g was delivered transvaginally at 38 weeks and 6 days gestation. The patient had Apgar scores of 8 and 9, respectively. The tension in the fontanel was soft. The head circumference was 34 cm (+0.62SD). The patient showed no neurological deficits. At birth, the initial MRI, including 3D-heavily T2-weighted MRI (3D-hT2WI), demonstrated multiple cysts with smooth and rounded borders and a nonenhancing wall in the right parieto-occipital region. The cyst contents were nearly isointense to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) but varied in intensity in each lesion [

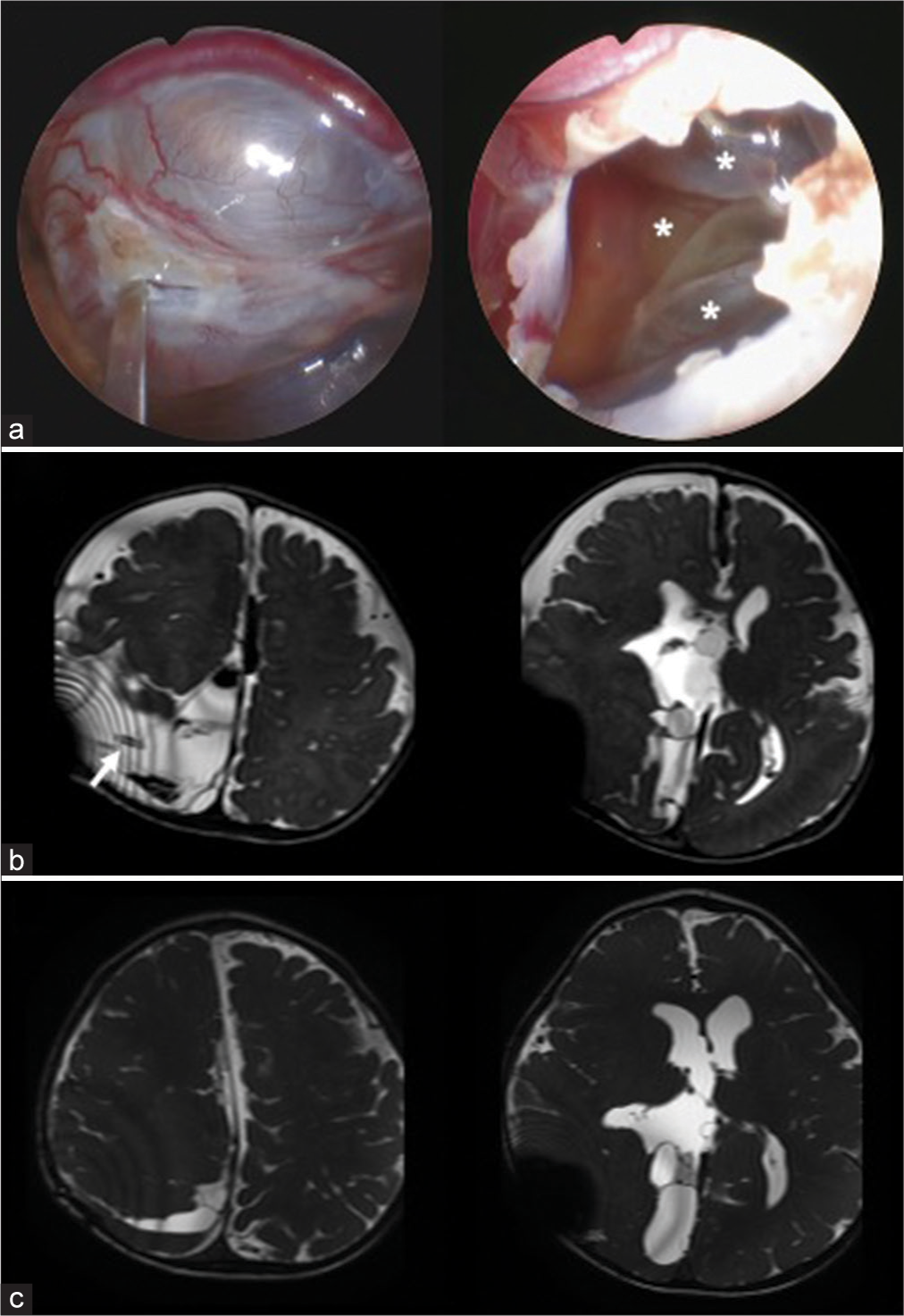

Postoperatively, the tension in his fontanel became soft, and vomiting disappeared. 3D-hT2WI performed 4 days after the second surgery revealed that the size of the cyst had decreased [

Figure 2:

(a) Intraoperative photographs of neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration. Multiple cysts are shown inside a huge cyst performed wall fenestration (asterisks). (b) 3D-hT2WI 4 days after the operation, revealing the volume of the huge cyst decreased, and cyst-peritoneal shunt was placed into the huge cyst (white arrow). (c) 3D-hT2WI 1 year after operation depicting the volume of the cyst more decreased.

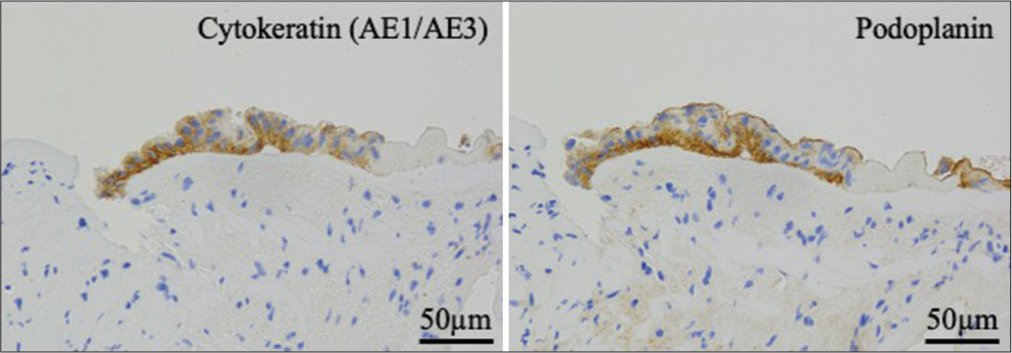

Pathological examination revealed that the cyst wall was mainly composed of fibroconnective tissue and was partially lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells. A ciliated epithelium was also observed, but goblet cells were not observed. The lining cells were immunopositive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and podoplanin [

DISCUSSION

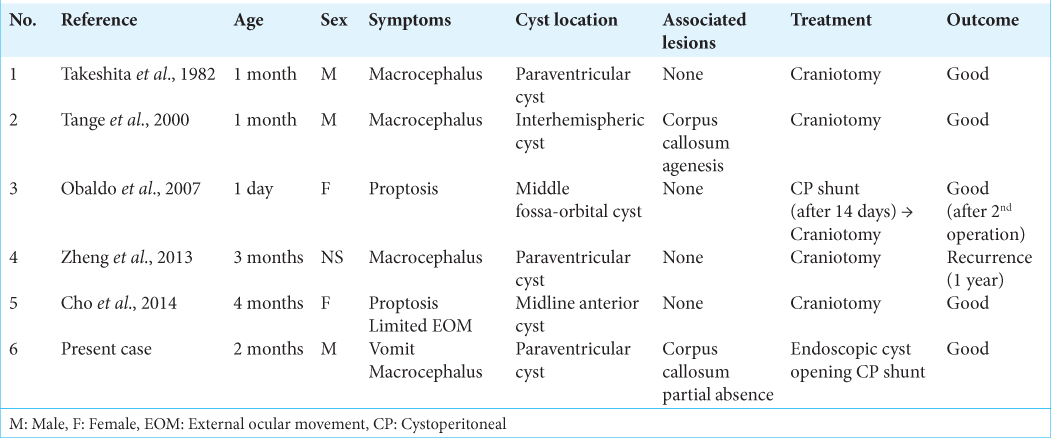

GECs have several anatomical and clinical characteristics. First, they can originate from different intracranial locations, including the intraparenchymal, intraventricular, and subarachnoid spaces.[

For asymptomatic GECs, surgical treatment is typically not necessary. However, symptomatic patients tend to present with symptoms related to increased intracranial pressure, and local mass effect surgical treatment is needed. Common surgical approaches for GECs include burr hole opening for evacuation of the fluid component, open craniotomy for total extirpation, open cysto-ventricular fenestration, cystosubarachnoid shunting, partial cyst excision, cystoperitoneal shunt, or a combination of these approaches.[

There is a concern about shunt malfunction or obstruction for patients who underwent CP shunting, and we believe that this combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and CP shunt is a minimally invasive and considerable treatment for infant patients with GECs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an infant treated using this minimally invasive combined surgical procedure.

CONCLUSION

Combined neuroendoscopic cyst wall fenestration and CP shunt is a minimally invasive and effective treatment for infants with GECs.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

References

1. Alvarado AM, Smith KA, Chamoun RB. Neuroendoscopic fenestration of glioependymal cysts to the ventricle: Report of 3 cases. J Neurosurg. 2018. 131: 1615-9

2. Cho HJ, Kim HN, Kim KJ, Lee KS, Myung JK, Kim SK. Intracranial extracerebral glioneuronal heterotopia with adipose tissue and a glioependymal cyst: A case report and review of the literature. Korean J Pathol. 2014. 48: 254-7

3. Frazier J, Garonzik I, Tihan T, Olivi A. Recurrent glioependymal cyst of the posterior fossa: an unusual entity containing mixed glial elements. Case report. J Neurooncol. 2004. 68: 13-7

4. Friede RL, Yasargil MG. Supratentorial intracerebral epithelial (ependymal) cysts: Review, case reports, and fine structure: Review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977. 40: 127-37

5. Morigaki R, Shinno K, Pooh KH, Nakagawa Y. Giant glioependymal cyst in an infant. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011. 7: 175-8

6. Obaldo RE, Shao L, Lowe LH. Congenital glioependymal cyst presenting with severe proptosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007. 28: 999-1000

7. Osborn AG, Preece MT. Intracranial cysts: Radiologic-pathologic correlation and imaging approach. Radiology. 2006. 239: 650-64

8. Robles LA, Paez JM, Ayala D, Boleaga-Duran B. Intracranial glioependymal (neuroglial) cysts: A systematic review. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 2018. 160: 1439-49

9. Takeshita M, Miyazaki T, Kubo O, Kagawa M, Saito Y, Kitamura K. Paraventricular cerebral cyst in an infant. Surg Neurol. 1982. 17: 123-6

10. Tange Y, Aoki A, Mori K, Niijima S, Maeda M. Interhemispheric glioependymal cyst associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2000. 40: 536-42

11. Zheng SP, Ju Y, You C. Glioependymal cyst in children: A case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013. 115: 2288-90