- Department of Neurosurgery, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan

- Department of Clinical Laboratory Medicine, Division of Diagnostic Pathology, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Naoki Nitta, Department of Neurosurgery, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1040_2022

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Satoshi Aoyama1, Naoki Nitta1, Suzuko Moritani2, Atsushi Tsuji1. Cranial vault lymphoma – A case report and characteristics contributing to a differential diagnosis. 24-Mar-2023;14:107

How to cite this URL: Satoshi Aoyama1, Naoki Nitta1, Suzuko Moritani2, Atsushi Tsuji1. Cranial vault lymphoma – A case report and characteristics contributing to a differential diagnosis. 24-Mar-2023;14:107. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12206/

Abstract

Background: Lymphomas of the cranial vault are rare and are often misdiagnosed preoperatively as presumptive meningioma with extracranial extension.

Case Description: A 58-year-old woman was referred and admitted to our department with a rapidly growing subcutaneous mass over the right frontal forehead of 2 months’ duration. The mass was approximately 13 cm at its greatest diameter, elevated 3 cm above the contour of the peripheral scalp, and attached to the skull. Neurological examination showed no abnormalities. Skull X-rays and computed tomography showed preserved original skull contour despite the large extra and intracranial tumor components sandwiching the cranial vault. Digital subtraction angiography showed a partial tumor stain with a large avascular area. Our preoperative diagnostic hypothesis was meningioma. We performed a biopsy and histological findings were characteristic of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. A very high preoperative level of soluble interleukin-2 receptor (5390 U/mL; received postoperatively) also suggested lymphoma. The patient received chemotherapy but died of disease progression 10 months after the biopsy.

Conclusion: Several preoperative features of the present case are clues to the correct diagnostic hypothesis of cranial vault diffuse large B-cell lymphoma rather than meningioma, including a rapidly growing subcutaneous scalp mass, poor vascularization, and limited skull destruction relative to the size of the soft-tissue mass.

Keywords: Calvarial lymphoma, Calvarium, Cranial vault lymphoma, Skull

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma initially appearing in the calvarium is uncommon. Only about 40 cases have been reported, and when all histological types of lymphoma are included, only about 120 cases appearing in the calvarium have been reported.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

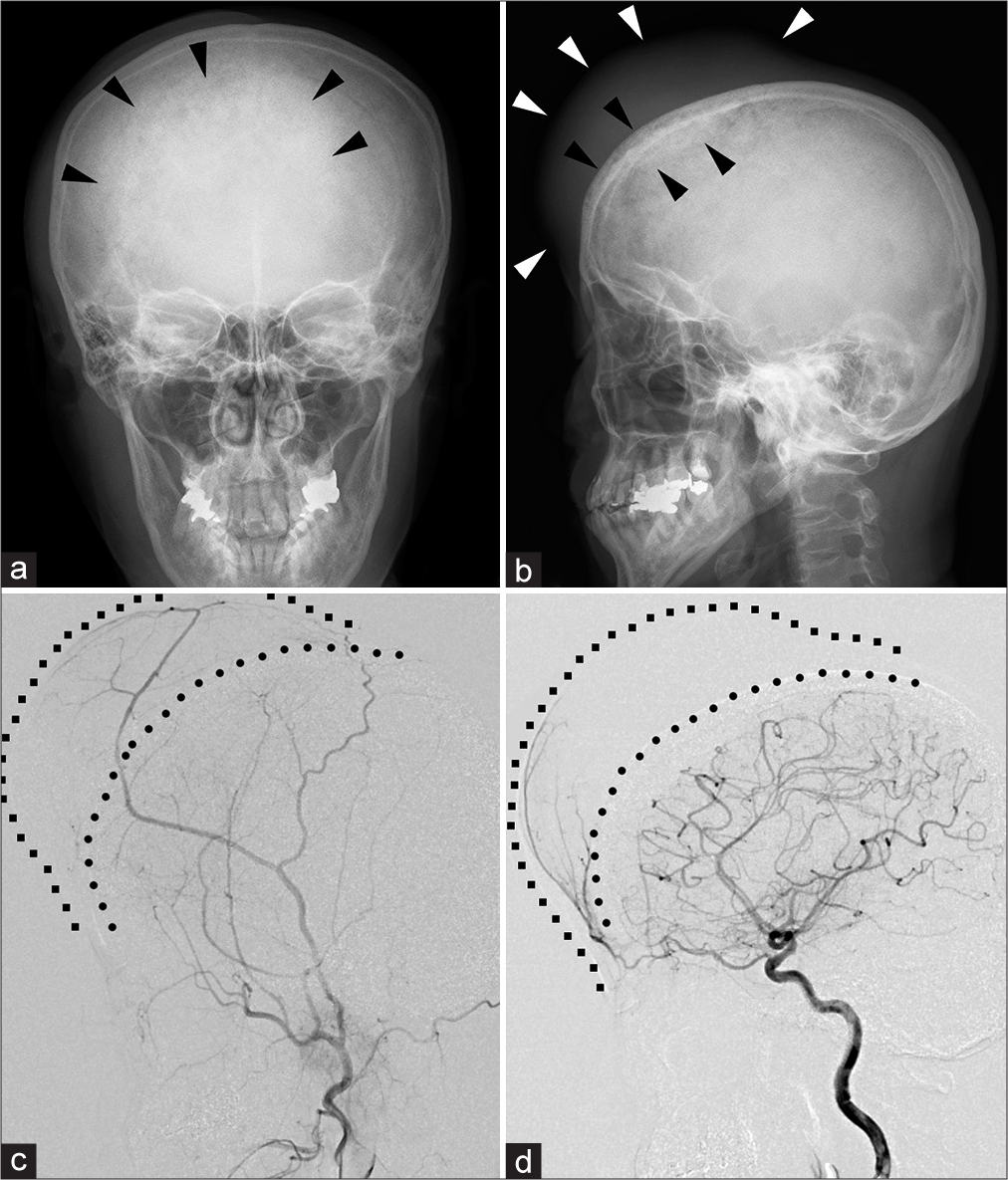

A 58-year-old woman was referred and admitted to our department for surgical treatment with a rapidly growing subcutaneous mass and pain over the right frontal forehead of 2 months’ duration. She presented with mild ptosis of her right eye associated with the mass. She had no history of head injury, serious illnesses, operations, or hospitalizations. The mass was approximately 13 cm at its greatest diameter, elevated 3 cm above the contour of the peripheral scalp, firm, nonpulsatile, mildly tender, and attached to the skull; the skin overlying the area was stretched and reddish. Neurological examination showed no abnormalities. She was afebrile. Laboratory tests, performed as routine preoperative testing and to detect other lesions, showed abnormally high levels of lactate dehydrogenase (13.58 µkat/L, normal range: 1.99‒3.82 µkat/L), alkaline phosphatase (6.43 µkat/L, normal range: 1.92‒5.98 µkat/L), amylase (3.07 µkat/L, normal range: 0.62‒2.09 µkat/L), and lipase (12.75 µkat/L; normal range: 0.17‒0.83 µkat/L). Beta-2-microglobulin, a marker of malignant lymphoma and obtained with other tumor markers to screen for the possibility of primary malignant tumors in other organs, was normal. The patient was not immunocompromised and tested negative for human immunodeficiency virus. Skull X-rays showed slight permeative deossification of the outer table and diploic space, sclerosis of the inner table, and preserved outline of the skull underlying the subcutaneous tumor [

Figure 1:

Preoperative X-ray and digital subtraction angiography. (a and b) Skull X-ray. Note mixture of permeative deossification and sclerosis with preserved outline of the skull (black arrowheads) underlying the subcutaneous tumor (white arrowheads). (c and d) Lateral digital subtraction angiography of the right external carotid artery (c) and right internal carotid artery (d). The angiograph shows poor vascularization of the extracranial and intracranial compartments of the tumor from both the external and internal carotid artery circulations. Line of circles: the outer table of the skull; line of squares: the contour of the skin.

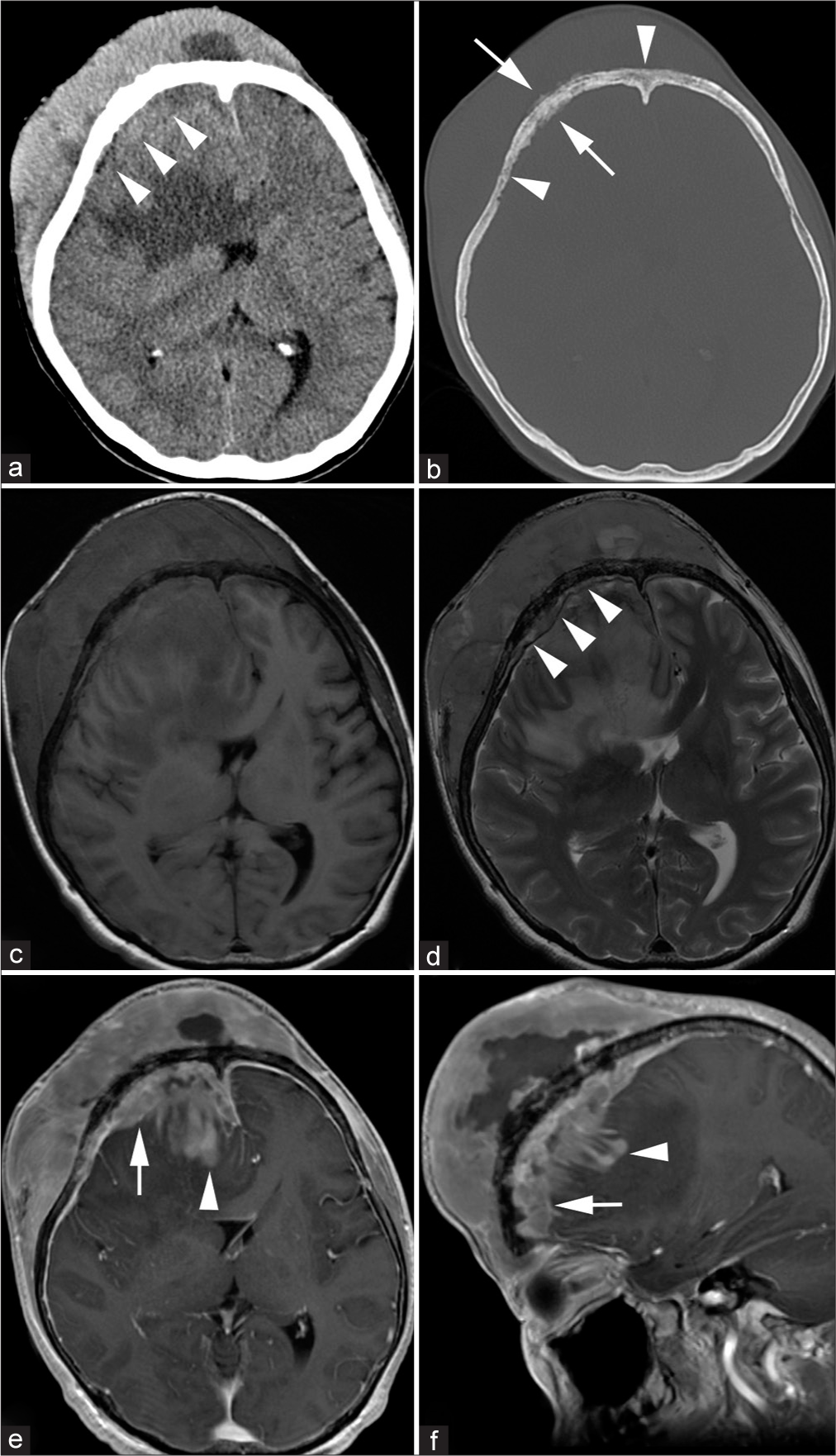

Figure 2:

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging. (a and b) Axial CT of the brain parenchyma window (a) and the bone window (b). The large extracranial component and relatively small intracranial component (arrowheads on [a]) sandwiched the cranial vault with permeative deossification (arrowheads on [b]) and periosteal reaction (arrows on [b]). (c-f) T1-weighted imaging (c), T2-weighted imaging (d), and post contrast T1-weighted imaging in the axial plane (e) and sagittal plane (f). The dura mater is raised from the cranial vault (arrowheads on [d]), and subdural extension (arrows on [e] and [f]) and brain invasion (arrowheads on [e] and [f]) are observed. Note that the cranial vault contour is preserved despite the large mass size in (b).

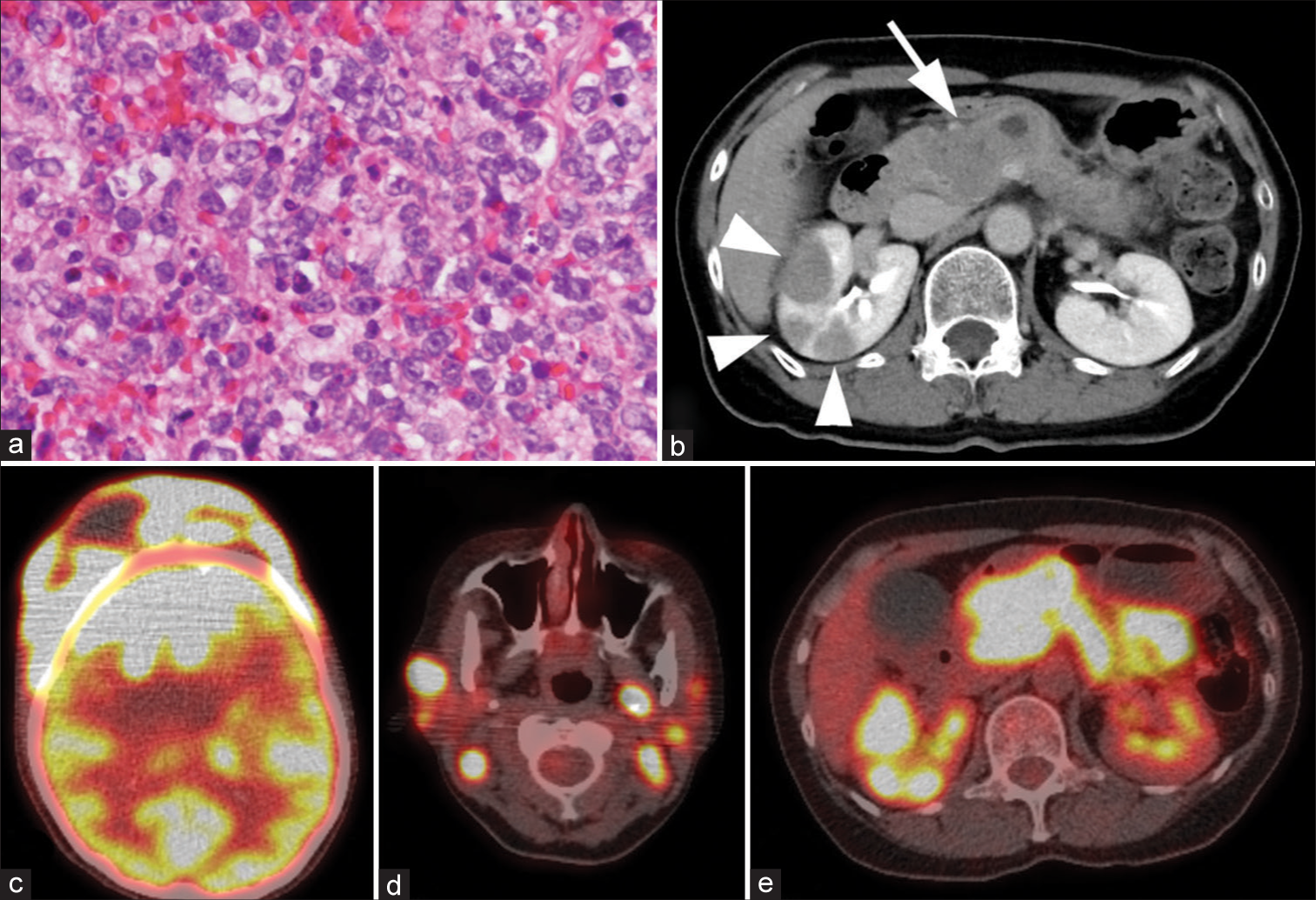

Figure 3:

Histopathological features of the tumor and metastatic lesions. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the tumor at ×400 magnification, (b) post contrast axial computed tomography of the abdomen, and (c-e) fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) of the head (c), neck (d), and abdomen (e). The cranial vault lymphoma shows a stronger signal on FDG-PET than does the brain (c). Note metastatic lesions in the lymph nodes of the neck (d) and in the pancreas (arrow on [b] and strong signal in [e]) and kidneys (arrowheads on [b] and strong signal in [e]).

The patient received one course of chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) and then one course of CHOP with rituximab (R-CHOP) in the hematology department of our hospital. The tumor, including the intracranial component, shrank markedly after the R-CHOP therapy. To treat the intracranial extension of the tumor, the patient received one course of intrathecal prednisolone, methotrexate, and cytarabine. She was well 2.5 months after the biopsy and was transferred to the hematology department of the hospital near her house to continue chemotherapy. She died of disease progression 10 months after the biopsy.

DISCUSSION

We have reported a case of cranial vault lymphoma. Its preoperative diagnostic hypothesis was meningioma, but the histological and immunohistochemical findings, as well as the sIL2R positivity, led us to diagnose it as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. We conclude that when a subcutaneous tumor with intracranial extension is encountered, cranial vault lymphoma should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

The present case was a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma initially appearing in the calvarium. There is general agreement that cases with a solitary lesion arising in a bone should be considered as a primary bone lymphoma, whereas a lymphoma that has arisen in soft tissues, lymph nodes, or other organs and infiltrates an adjacent bone secondarily should be considered to be secondary bone lymphoma.[

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging characteristics of the present case to specify the features helpful for differentiating lymphomas of the cranial vault from meningiomas. When a tumor with intra and extracranial extension sandwiching the skull is seen, meningioma with extracranial extension is often first suspected. We have experienced many cases of convexity meningioma, which is the most representative of the intracranial tumors that attach to the dura matter, and empirically, we know that in a few cases convexity meningiomas infiltrate the skull and extend into the extracranial subcutaneous space. Several of our findings from our case and the literature can be clues for the preoperative diagnosis of cranial vault lymphoma rather than meningioma with extracranial extension: (1) a rapidly growing subcutaneous scalp mass; (2) poor tumor vascularization; and (3) mild and disproportionately small skull destruction on images compared with the soft-tissue mass. The high preoperative level of sIL2R in laboratory tests and higher uptake of FDG than the brain parenchyma on FDG-PET is also suggestive of lymphoma rather than meningioma.[

In the case of extracranial extension of meningioma or intraosseous meningioma, the tumors tend to be slow-growing.[

Consistent with other reports,[

Lymphoma cells have been suggested to infiltrate the spaces within the diploe and to extend along the emissary veins to infiltrate the soft tissues on either side of the bone.[

Laboratory data are unremarkable in many cases.[

In our case, the tumor showed high uptake of FDG on FDG-PET [

CONCLUSION

Cranial vault lymphoma is a rare entity among skull tumors and its preoperative diagnostic hypothesis is often meningioma with extracranial extension. A rapidly growing subcutaneous scalp mass, poor vascularization on angiography, mild, and disproportionately small skull destruction despite the large size of the extracranial and/ or intracranial component, as well as an increased level of sIL2R in laboratory tests and higher uptake of FDG than the brain parenchyma on FDG-PET, are suggestive of lymphoma rather than meningioma.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Aquilina K, O’Brien DF, Phillips JP. Diffuse primary nonHodgkin’s lymphoma of the cranial vault. Br J Neurosurg. 2004. 18: 518-23

2. Banker H, Shah D, Modi H, Salvi B. Extra cranial invasive meningioma of fronto-temporo-parietal region of the skull vault. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. 2012: bcr1220115290

3. Bradač GB, Ferszt R, Kendall BE, editors. Cranial Meningiomas. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; 1990. p.

4. El Asri AC, Akhaddar A, Baallal H, Boulahroud O, Mandour C, Chahdi H. Primary lymphoma of the cranial vault: Case report and a systematic review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2012. 154: 257-65 discussion; 265

5. Galldiks N, Albert NL, Sommerauer M, Grosu AL, Ganswindt U, Law I. PET imaging in patients with meningioma-report of the RANO/PET group. Neuro Oncol. 2017. 19: 1576-87

6. Gomez CK, Schiffman SR, Bhatt AA. Radiological review of skull lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018. 9: 857-82

7. Holtås S, Monajati A, Utz R. Computed tomography of malignant lymphoma involving the skull. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985. 9: 725-7

8. Jang SY, Kim CH, Cheong JH, Kim JM. Extracranial extension of intracranial atypical meningioma en plaque with osteoblastic change of the skull. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014. 55: 205-7

9. Kanaya M, Endo T, Hashimoto D, Endo S, Takemura R, Okada K. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a bulky mass in the cranial vault. Int J Hematol. 2017. 106: 147-8

10. Kosugi S, Kume M, Sato J, Sakuma I, Moroi J, Izumi K. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with mass lesions of skull vault and ileocecum. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2013. 53: 215-9

11. Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningiomas--a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974. 34: 728-44

12. Messina C, Christie D, Zucca E, Gospodarowicz M, Ferreri AJ. Primary and secondary bone lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015. 41: 235-46

13. Nahm WJ, Gordhandas J, Hinds B. Atypical presentation of transcranial extension of intracranial meningiomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022. 44: 207-11

14. Nitta N, Moritani S, Fukami T, Nozaki K. Characteristics of cranial vault lymphoma from a systematic review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int. 2022. 13: 231

15. Ostrowski ML, Unni KK, Banks PM, Shives TC, Evans RG, O’Connell MJ. Malignant lymphoma of bone. Cancer. 1986. 58: 2646-55

16. Pear BL. Skeletal manifestations of the lymphomas and leukemias. Semin Roentgenol. 1974. 9: 229-40

17. Perry A, Louis DN, Budka H, Von Deimling A, Sahm F, Rushing EJ, Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. Meningioma. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: International Agency for Researcher on Cancer; 2016. p.

18. Pui CH, Ip SH, Kung P, Dodge RK, Berard CW, Crist WM. High serum interleukin-2 receptor levels are related to advanced disease and a poor outcome in childhood nonHodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1987. 7: 624-8

19. St. Clair EG, McCutcheon IE, editors. Skull Tumors. Youmans Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011. p.

20. Sugimoto KJ, Shimada A, Ichikawa K, Wakabayashi M, Sekiguchi Y, Izumi H. Primary platelet-derived growth factor-producing, spindle-shaped diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the skull: A case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014. 7: 4381-90

21. Xing Z, Huang H, Xiao Z, Yang X, Lin Y, Cao D. CT, conventional, and functional MRI features of skull lymphoma: A series of eight cases in a single institution. Skeletal Radiol. 2019. 48: 897-905