- Norton Neuroscience Institute, Norton Healthcare, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Norton Leatherman Spine Center, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

- Department of Anatomical Science and Neurobiology, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

Correspondence Address:

Christopher B. Shields

Norton Neuroscience Institute, Norton Healthcare, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

Department of Anatomical Science and Neurobiology, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.198732

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Lisa B. E. Shields, Lisa Clark, Steven D. Glassman, Christopher B. Shields. Decreasing hospital length of stay following lumbar fusion utilizing multidisciplinary committee meetings involving surgeons and other caretakers. 19-Jan-2017;8:5

How to cite this URL: Lisa B. E. Shields, Lisa Clark, Steven D. Glassman, Christopher B. Shields. Decreasing hospital length of stay following lumbar fusion utilizing multidisciplinary committee meetings involving surgeons and other caretakers. 19-Jan-2017;8:5. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/decreasing-hospital-length-of-stay-following-lumbar-fusion-utilizing-multidisciplinary-committee-meetings-involving-surgeons-and-other-caretakers/

Abstract

Background:Although hospital length of stay (LOS) following lumbar fusion has decreased for a variety of reasons, different institutions find their LOS over the benchmarks published by the national Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Over a 3-year period, this prospective study introduced utilization of multidisciplinary committee meetings between surgeons and other caretakers to decrease LOS following spinal fusion surgery without compromising the quality of care.

Methods:A multidisciplinary committee was established to assess factors and institute recommendations that influence hospital LOS following lumbar fusion compared to the national compared to the national AHRQ benchmark at baseline and at 1 and 2 years after adjusting our standard practice. We also analyzed re-admission rates at 7 and 30 days and determined the average variable direct cost.

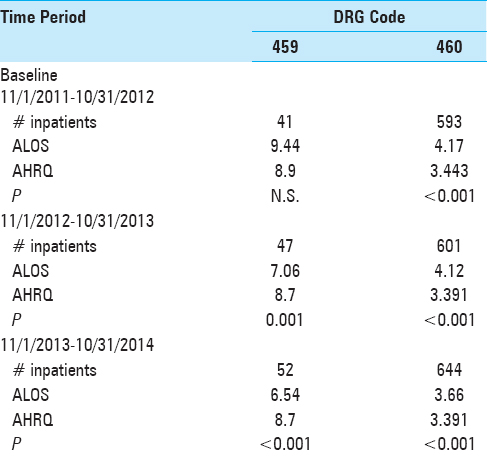

Results:While the national AHRQ benchmark average LOS (ALOS) was statistically better for DRGs 459 and 460 for all three years except for DRG 459 in the baseline year compared to our ALOS, we observed improvement in the ALOS for both DRG 459 and 460 throughout the 3 years of the study. ALOS for DRG 460 was statistically different for 2011–2012 vs 2013–2014 (P P P P = 0.001).

Conclusions:This study established an effective patient discharge plan, patient education, partnerships with rehabilitation facilities, and study review and discussion among physicians and staff. Further monitoring of factors that impact hospital LOS following lumbar fusion is warranted to curtail patient complications and organizational expenditures while providing superior medical care.

Keywords: Cost, fusion, hospital stay, lumbar, spine

INTRODUCTION

Spine-related health-care expenses totaled $86 billion in 2005, a 65% increase from 1997.[

Several factors have been identified as increasing postoperative LOS and/or readmission in patients undergoing lumbar fusions, including increased age, increased body mass index, number of levels fused, American Society of Anesthesiologists class 3–4, preoperative hematocrit <36.0, and steroid use.[

A multidisciplinary committee was established at our Institution in 2012 to investigate why our hospital LOS data for lumbar fusion was significantly greater than the national Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) benchmark. We identified and corrected six areas integrally related to complex lumbar spine surgery, which resulted in a significant decrease in LOS.

In the current study, we present our findings of the average LOS (ALOS) compared to the national AHRQ benchmark, the average variable direct cost, and the re-admission rates at 7 and 30 days postoperatively for lumbar fusion with and without major comorbidities over a 3-year time span. We also discuss physician and patient expectations of LOS and analyze factors that play a role in expediting a patient's postoperative hospital stay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

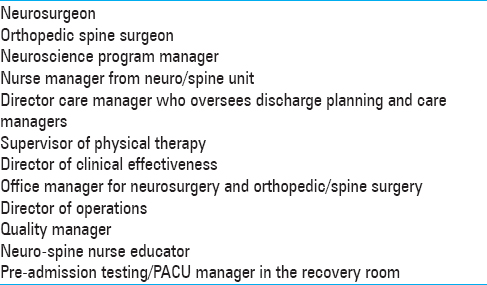

Under an institutional review board-approved protocol, the current prospective study (11/1/2011–10/31/2014) was conducted in a 500-bed tertiary spine center with a total spine volume of approximately 2650 cases annually. The cases consisted of lumbar fusion and instrumentation with the DRG codes 459 and 460. DRG 459 denotes spine fusion except cervical with major comorbidities. DRG 460 includes cases of spine fusion except cervical without major comorbidities. A multidisciplinary committee was established at our Institution to assess the various aspects that may play a role in influencing LOS after lumbar fusion [

Prior to the study, each spine (neurosurgery and orthopedic) surgeon was asked about their ALOS for a patient undergoing a lumbar fusion. Surgeons frequently left discharge planning to the physical therapists, discharge planners, and nurses. The LOS data for DRG codes 459 and 460 at our Institution were evaluated over 3 years; (1) baseline – initial multidisciplinary committee meeting (11/1/2011 to 10/31/2012); 2) 1 year later (11/1/2012 to 10/31/2013); and 3) 2 years later (11/1/2013 to 10/31/2014). The average LOS data were compared to the national AHRQ benchmark, the re-admission rates were analyzed at 7 and 30 days following hospital discharge after lumbar fusion, and the average variable direct cost was calculated to determine whether there was an organizational cost saving when patients have a shorter hospital LOS following lumbar fusion. Our Institution does not provide the actual costs of hospital care and, therefore, we presented the cost savings as a percentage change.

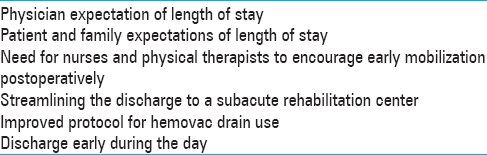

The multidisciplinary committee identified six factors that play a significant role in decreasing the hospital LOS following lumbar fusion [

Statistical analysis

For the 459 and 460 diagnosis codes, the ALOS for each of the 3 years was compared to the national AHRQ benchmark using one-sample t-tests. Yearly ALOS within codes 459 and 460 were compared with each other using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey HSD post hoc t-tests. The differences in cost per year between 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 were compared to the cost value for 2011–2012 using one-sample t-tests.

RESULTS

Yearly average length of stay compared to AHRQ benchmark and to each year following lumbar fusion

There was a noticeable improvement in the ALOS for both DRG 459 and 460 throughout the 3 years of this study. When the ALOS was compared to the national AHRQ benchmark for the 3-year time period (11/1/2011 to 10/31/2014), the national AHRQ benchmark ALOS was statistically better for both DRGs 459 and 460 for all 3 years of study except for DRG 459 in the baseline year compared to the ALOS at our Institution [

The analysis of ALOS comparing each year with each other for DRG 459 was not significant by ANOVA. When the yearly ALOS was compared to each other for both DRGs 459 and 460, the ALOS for DRG 460 for each year vs. benchmark data was statistically significant by ANOVA (P < 0.001). The ALOS for DRG 460 was statistically different for 2013–2014 (3.66) vs 2011–2012 (4.17) (P < 0.001) and 2013–2014 (3.66) vs 2012–2013 (4.12) (P < 0.001) although not for 2011–2012 (4.17) vs 2012–2013 (4.12), as discerned by the Tukey HSD post hoc t-test.

Average variable direct cost

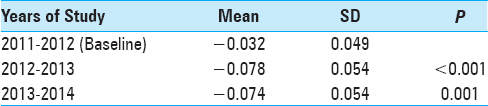

There was a statistically significant difference comparing the cost change from both 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 compared to the baseline (2011–2012) [

Readmission rates at 7 and 30 days following hospital discharge after lumbar fusion

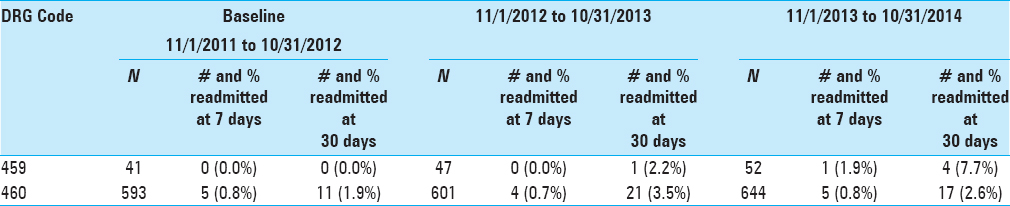

The readmission rates at both 7 and 30 days following hospital discharge after lumbar fusion for DRGs 459 and 460 were similar for the three periods [

DISCUSSION

Decreasing the length of hospital stay following lumbar fusion is an integral factor in promoting cost-effective medical care. In their study of 103 patients undergoing open 1- to 3-level posterior lumbar fusion, Gruskay et al. reported an average LOS of 3.6 ± 1.8 days (mean ± SD) (range of 0 to 12 days).[

Reduced length of stay with minimally invasive vs. open lumbar fusions

Minimally invasive lumbar fusions resulted in shorter LOS compared with open procedures. In a study by Siemionow et al. involving 104 patients undergoing a 1-level minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), 78 patients were discharged more than 24 hours postoperatively, and their mean LOS was 4 ± 2 days.[

Improvement utilizing multidisciplinary meetings to decrease length of stay following lumbar fusions

We observed an improvement in our Institution's ALOS for both DRG 459 and 460 throughout the 3 years of study [

Decreased average length of stay directly correlated with cost savings

Both the ALOS and the average variable direct cost were significantly lowered over the course of our study. There was a statistically significant difference comparing the cost change from both 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 compared to the baseline (2011–2012) [

Surgeon's perspective of average length of stay following lumbar fusions

A striking aspect of the present study was the surgeon's perspective on the appropriate LOS following lumbar fusion. The LOS in the studies by Wang et al. and Gruskay et al. studies was prolonged due to complications,[

Surgeon related factors impact average length of stay

Surgeon-related factors in relation to LOS after lumbar fusion are seldom addressed in the literature. Gruskay et al. reported that older and sicker patients were more likely to remain in the hospital longer and that surgeon- and hospital-related factors had little effect.[

Identification of multiple factors may reduce average length of stay following lumbar surgery

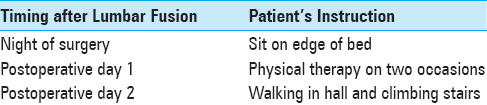

The authors found that the identification of multiple factors contributed to reducing ALOS following lumbar fusion surgery. Identifying patients prior to admission for lumbar fusion who may require care at a subacute/acute rehabilitation center postoperatively decreases the LOS. However, this is limited by mandatory hospital duration of at least 3 overnight stays following lumbar fusion in Medicare/Medicaid patients. The present study protocol for ambulation helped reduce ALOS [

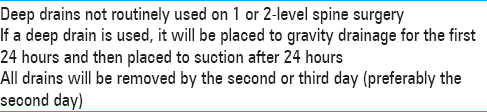

Use of and timing of drain removal impact average length of stay

The use and timing of drains in posterior lumbar fusions impact the ALOS. Walid et al. showed that posthemorrhagic anemia and allogeneic blood transfusion were statistically more common in patients with drains.[

Concern for early (e.g., within 7–30 days) postoperative readmission rate with reduced average length of stay

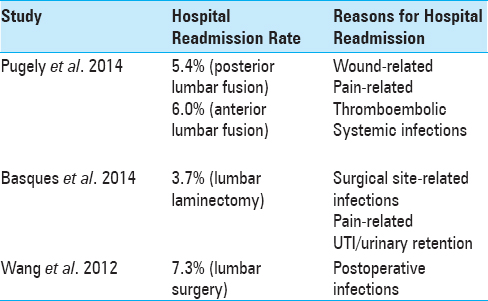

Several studies in the literature have addressed the reasons for hospital readmission within 30 days following a lumbar fusion [

The value of preoperative patient education in reducing average length of stay following lumbar fusion

Patient education is a valuable tool in decreasing LOS following lumbar fusion. McGregor et al. reported the importance of patient education following spinal surgery in an attempt to involve the patient in his/her own medical treatment.[

Revision of pain management protocols to reduce average length of stay

There were also modifications in the pain management protocol that included the use of a postoperative patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump for 24 hours. When the patients were able to take oral medications, they were given oral narcotics and muscle relaxants. Additional intravenous medications were administered for breakthrough pain as needed.

CONCLUSION

Future studies will analyze the lasting benefit of the six factors implemented at our Institution to decrease hospital LOS following lumbar fusion. Further scrutiny may elucidate additional factors which may play a role in shortening hospital stay following lumbar fusion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Basques BA, Fu MC, Buerba RA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, Grauer JN. Using the ACS-NSQIP to identify factors affecting hospital length of stay after elective posterior lumbar fusion. Spine. 2014. 39: 497-502

2. Basques BA, Varthi AG, Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Grauer JN. Patient characteristics associated with increased postoperative length of stay and readmission after elective laminectomy for lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2014. 39: 833-40

3. Bekelis K, Desai A, Bakhoum SF, Missios S. A predictive model of complications after spine surgery: The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) 2005-2010. Spine J. 2014. 14: 1247-55

4. Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Martin BI, Kreuter W, Goodman DC, Jarvik JG. Trends, major medical complications, and charges associated with surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in older adults. JAMA. 2010. 303: 1259-65

5. Gruskay JA, Fu MC, Bohl DD, Webb ML, Grauer JN. Factors affecting length of stay following elective posterior lumbar spine surgery: A multivariate analysis. Spine J. 2015. 15: 1188-95

6. Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey L. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine. 2004. 29: 79-86

7. Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Comstock BA, Hollingworth W. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008. 299: 656-64

8. McGregor AH, Burton AK, Sell P, Waddell G. The development of an evidence-based patient booklet for patients undergoing lumbar discectomy and un-instrumented decompression. Eur Spine J. 2007. 16: 339-46

9. McGregor AH, Dicken B, Jamrozik K. National audit of post-operative management in spinal surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006. 7: 47-

10. McGregor AH, Henley A, Morris TP, Dore CJ. Patients’ views on an education booklet following spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2012. 21: 1609-15

11. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Mendoza-Lattes S. Causes and risk factors for 30-day unplanned readmissions after lumbar spine surgery. Spine. 2014. 39: 2373-80

12. Siemionow K, Pelton MA, Hoskins JA, Singh K. Predictive factors of hospital stay in patients undergoing minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and instrumentation. Spine. 2012. 37: 2046-54

13. Street JT, Lenehan BJ, Dipaola CP, Boyd MD, Kwon BK, Paquette SJ. Morbidity and mortality of major adult spinal surgery. A prospective cohort analysis of 942 consecutive patients. Spine J. 2012. 12: 22-34

14. Walid MS, Abbara M, Tolaymat A, Davis JR, Waits KD, Robinson JS. The role of drains in lumbar spine fusion. World Neurosurg. 2012. 77: 564-8

15. Walid MS, Sahiner G, Robinson C, Robinson JS, Ajjan M, Robinson JS. Postoperative fever discharge guidelines increase hospital charges associated with spine surgery. Neurosurgery. 2011. 68: 945-9

16. Wang MC, Shivakoti M, Sparapani RA, Guo C, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Thirty-day readmissions after elective spine surgery for degenerative conditions among US Medicare beneficiaries. Spine J. 2012. 12: 902-11

17. Wang MY, Cummock MD, Yu Y, Trivedi RA. An analysis of the differences in the acute hospitalization charges following minimally invasive versus open posterior lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010. 12: 694-9

18. Weiss AJElixhauser AAndrews RMLast accessed on16 Oct 24. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb170-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2011.jsp .

19. Williamson E, White L, Rushton A. A survey of post-operative management for patients following first time lumbar discectomy. Eur Spine J. 2007. 16: 795-802

Mauricio Collada

Posted August 15, 2017, 5:34 pm

Applaud this paper, and hope these results encourage others to follow suite.

Our Salem Spine Center of Excellence in Salem, Oregon has been able to positively impact LOS, patient satisfaction, readmit rates, and provider satisfaction in all types of spine cases, including lumbar fusions, using the multi specialty governance committee concept presented in this wonderful paper.

We have used this concept also to impact outpatient spine care throughout our community. We have found key to our success in improving spine care is identifying best practices, developing treatment algorithms, working on standardization, and then pairing this up with a robust education program of PCPs for the community piece, and of patients when it comes to the hospital/surgical piece.