- Department of Spine Services , Indian Spinal Injuries Centre, New Delhi, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_512_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Sulaiman Sath. Does surgical decompression alleviate neglected cauda equina syndromes attributed to lumbar disc herniation and/or degenerative canal stenosis?. 05-Sep-2020;11:278

How to cite this URL: Sulaiman Sath. Does surgical decompression alleviate neglected cauda equina syndromes attributed to lumbar disc herniation and/or degenerative canal stenosis?. 05-Sep-2020;11:278. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10239/

Abstract

Background: Most studies recommend urgent decompression (e.g., within 48–72 h) of the symptomatic onset of a cauda equina syndrome. As patients in our area typically underwent >3 months delayed surgery for cauda equina syndromes due to disc disease/stenosis, we asked whether surgery was still worthwhile.

Methods: This was a retrospective analysis of 12 patients (2012–2018) who underwent delayed surgical decompression for cauda equina syndromes secondary to lumbar disc herniations and/or degenerative lumbar canal stenosis.

Results: After a mean postoperative duration of 8.22 months, nine patients experienced the complete restoration of bladder status; two patients required intermittent self-catheterization, while one patient had some residual symptoms (e.g., urgency but able to void with some difficulty).

Conclusion: For 12 patients who originally presented with cauda equina syndrome with complete incontinence, nine exhibited delayed full recovery of bladder function with average of 8.22 months postoperatively. We would, therefore, advise that delayed surgical decompression be offered to these patients, irrespective of the preoperative duration of cauda equina syndromes with complete incontinence.

Keywords: Bladder recovery, Cauda equina syndrome, Delayed presentation, Disc herniation, Lumbar canal stenosis, Neglected presentation

INTRODUCTION

Cauda equina syndrome most commonly occurs due to lumbar disc prolapse and/or degenerative lumbar canal stenosis.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

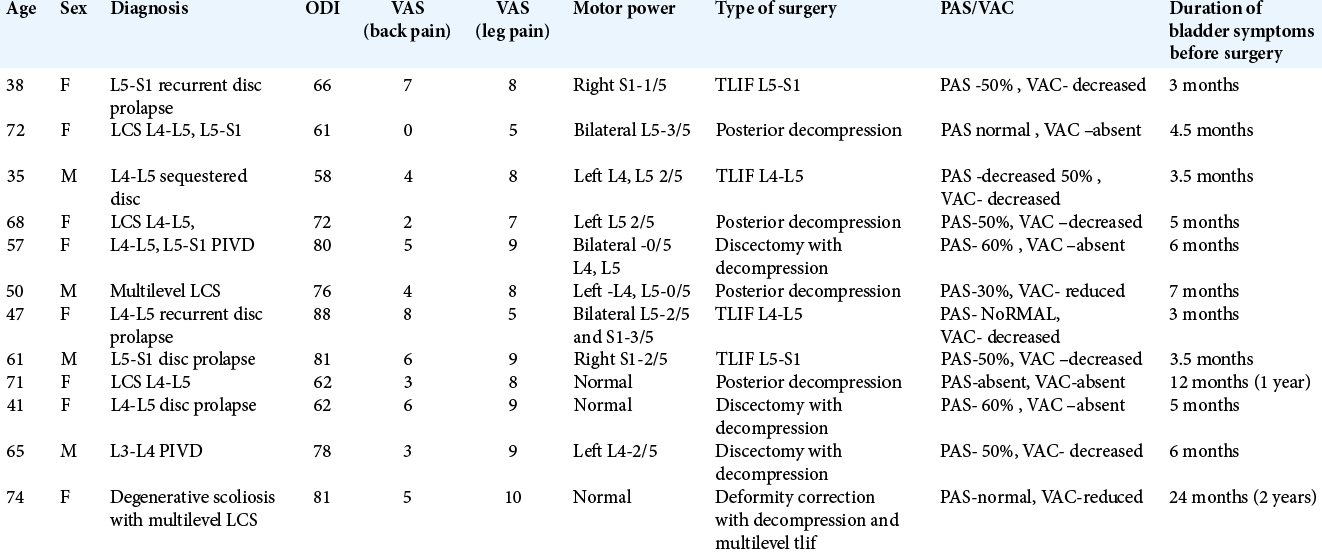

This was a retrospective study (2012–2018) of 12 patients undergoing delayed surgical decompression for cauda equina syndromes (e.g., >3 months/average 8.2 months) secondary to lumbar disc herniation/degenerative lumbar stenosis. Multiple variables were studied, but we predominantly focused on postoperative restitution of continence up to 2 years postoperatively [

All 12 patients were followed for a minimum period of 2 years and averaged 56.58 years of age. There were eight females and four males. Seven cases were due to prolapsed intervertebral discs; out of which two were recurrent, while five cases were secondary to lumbar canal stenosis, (two were multilevel lumbar canal stenosis, one of them associated with degenerative lumbar scoliosis). Preoperatively, six patients in our study had bladder retention and incontinence (cauda equina syndrome-retention [CES-R]), while six had incomplete bladder involvement (cauda equina syndrome – incomplete [CES-I]).

Bladder dysfunction histories

Duration of preoperative bladder symptoms ranged from 3 to 24 months (mean of 6.9 months. Patients with CES-I had relatively longer duration of symptoms before surgical intervention (mean of 8.250 months), while those with CES-R had relatively shorter duration of symptoms (mean of 5.500 months).

Surgery

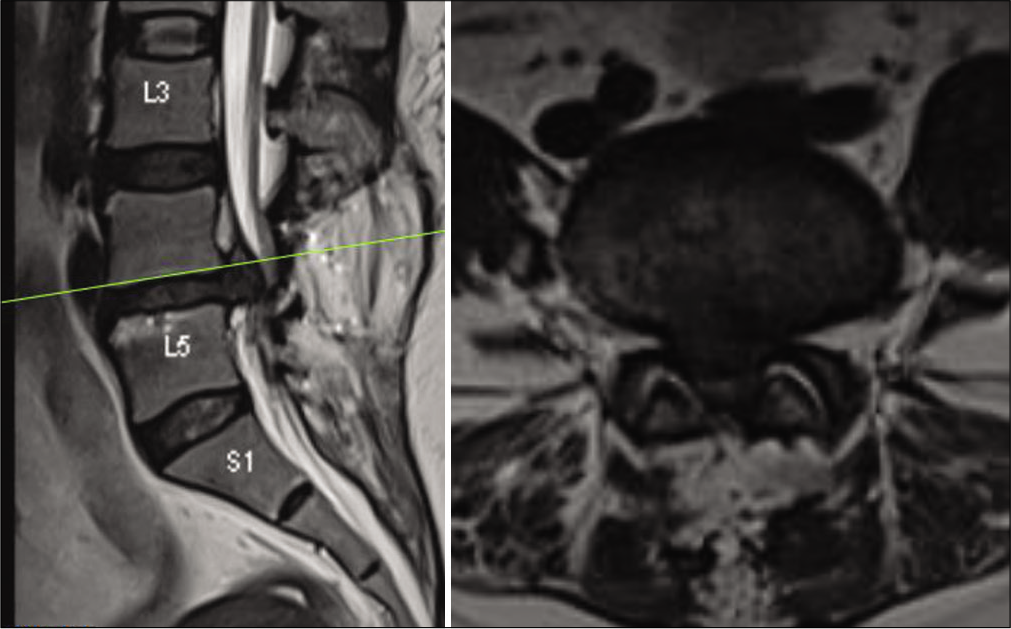

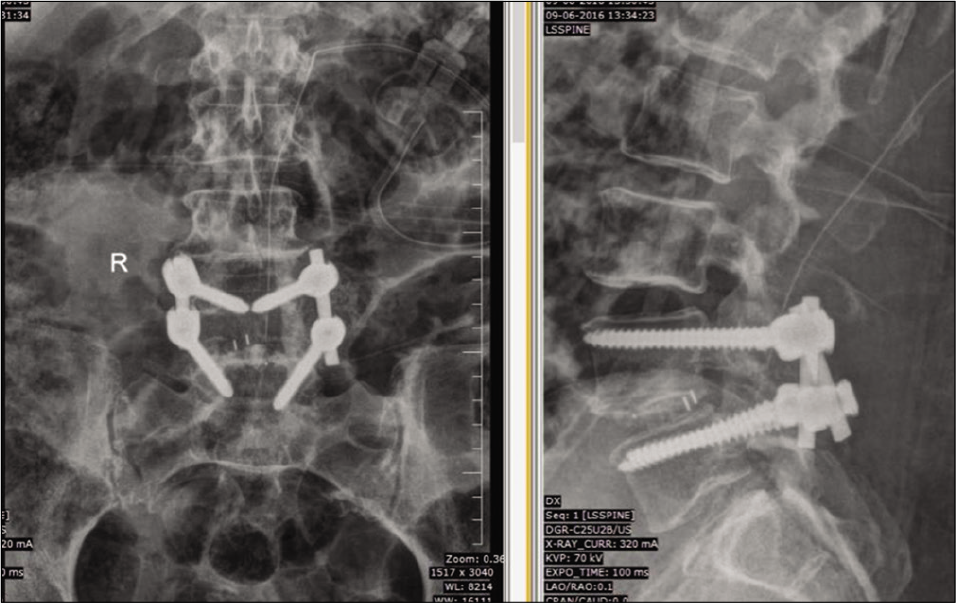

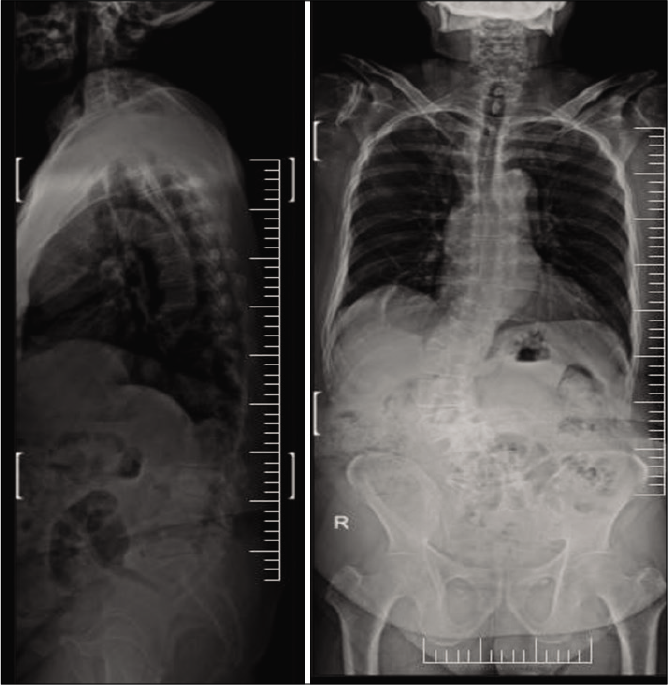

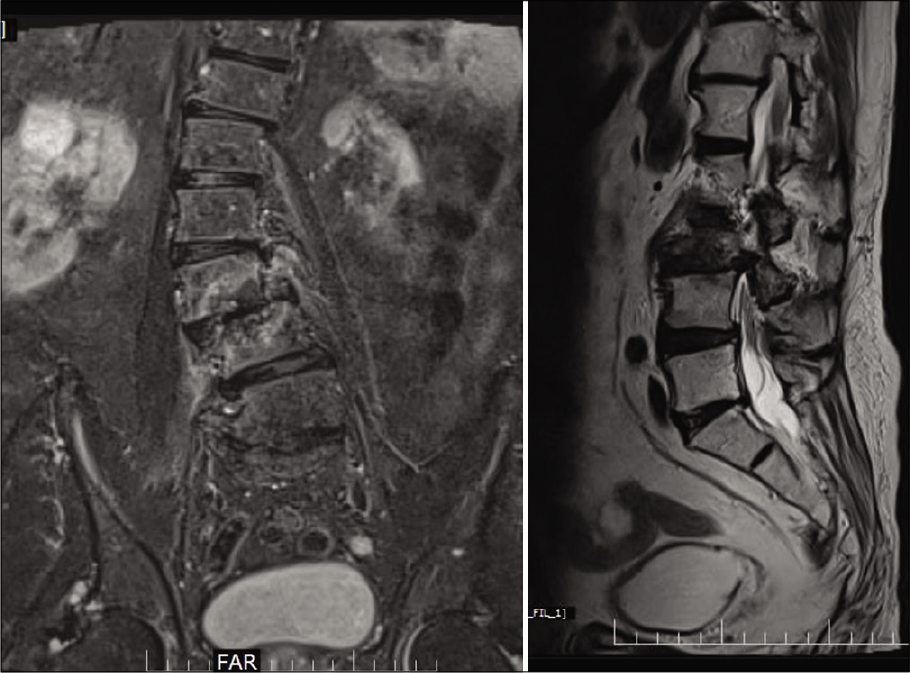

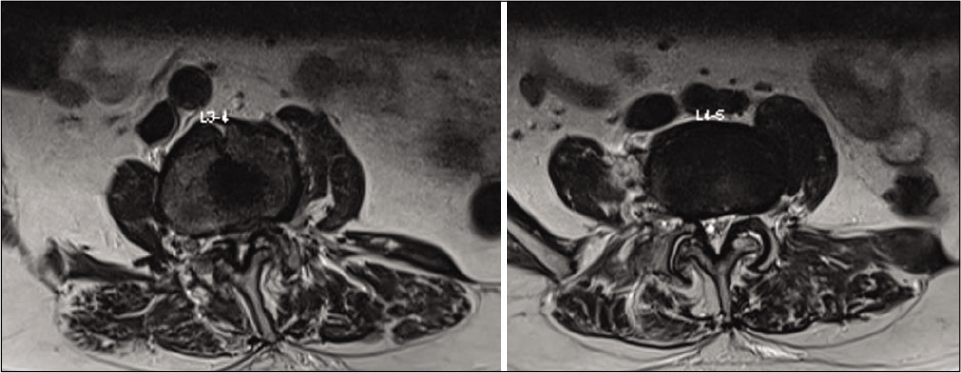

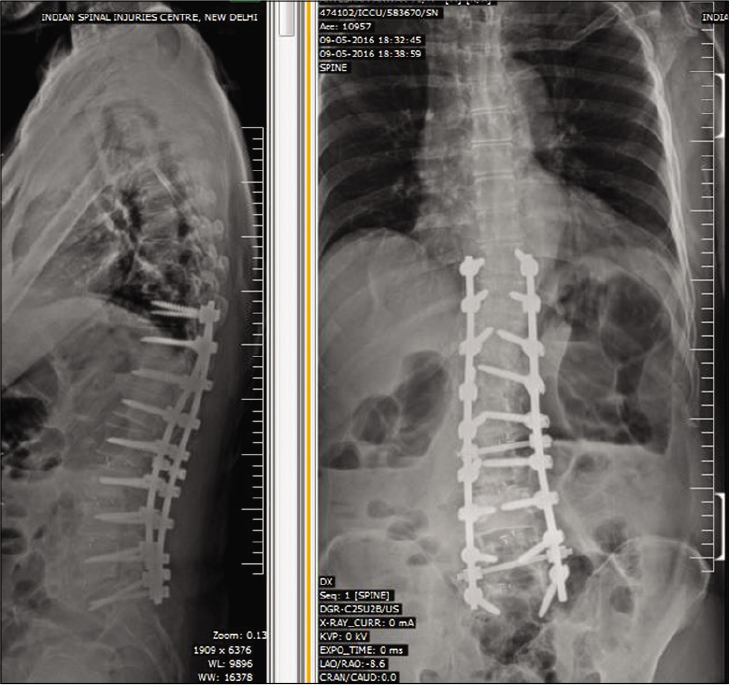

Posterior decompression alone or with discectomy was performed in seven patients, while five had discectomy/ decompression and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), with one additionally undergoing deformity correction in TLIF group. Representative pre-operative and post- operative radiological images of 2 patients in

Statistical evaluation

Descriptive statistics for continuous variables were presented in Mean ± Standard deviation and for categorical variables in count (n) and percentages (%). Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test was used to find association between two categorical variables. Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the correlation between the two continuous outcomes such as age, visual analog scale (VAS), and oswestry disability index (ODI). T-test of two independent means and one-way analysis of variance was used to find significant difference between the two groups and more than 2 groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and P-value is considered significant at 5% level.

RESULTS

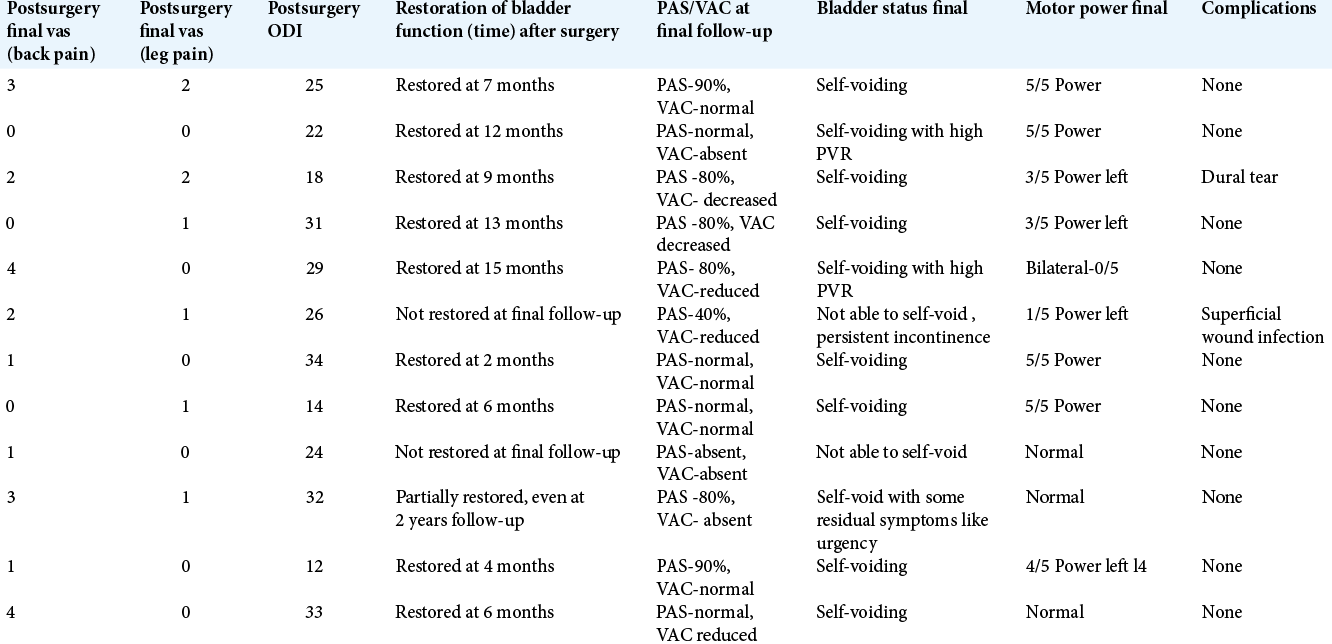

Outcomes

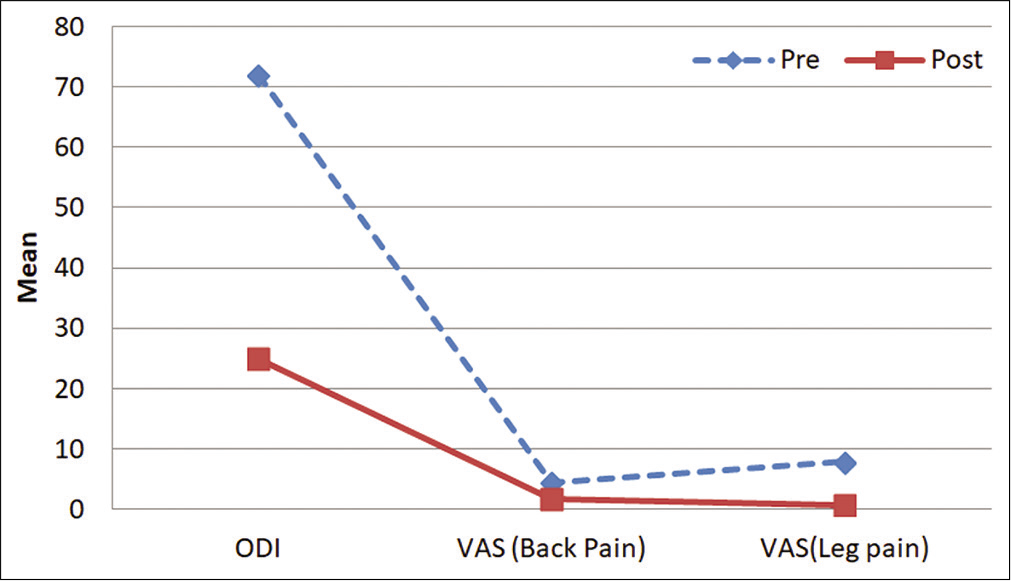

ODI and VAS preoperatively versus postoperatively [ Graph 1 ]

Mean ODI of our patients before surgery was 72.08 while at 2 years, it was 25. The VAS for back pain before surgery was 4.4 but at final follow-up was 1.75, while the mean VAS for leg pain before surgery was 7.9 and at final follow-up was 0.67 [

Motor function preoperatively versus postoperatively

Preoperatively, motor power was affected in nine patients, three of them had bilateral involvement of affected myotomes (among patients with bilateral involvement, one had complete motor loss), while six had unilateral involvement (among patients with unilateral involvement, one had complete motor power loss). The remaining three patients were normal. At final follow-up, motor power was normal in seven patients and affected in rest five patients (even among five affected patients, functional motor power was restored in three patients while two still had nonfunctional motor power).

Preoperative peri-anal Sensation)/voluntary anal contraction (PAS/VAC) versus postoperative

Preoperative PAS was normal in three patients, decreased in eight patients, and absent in one patient while PAS at final follow-up was normal in four patients, decreased in seven patients, and absent in one patient. Preoperative VAC was absent in four patients, decreased in eight patients while VAC at final follow-up was normal in four patients, decreased in five patients, and absent in three patients.

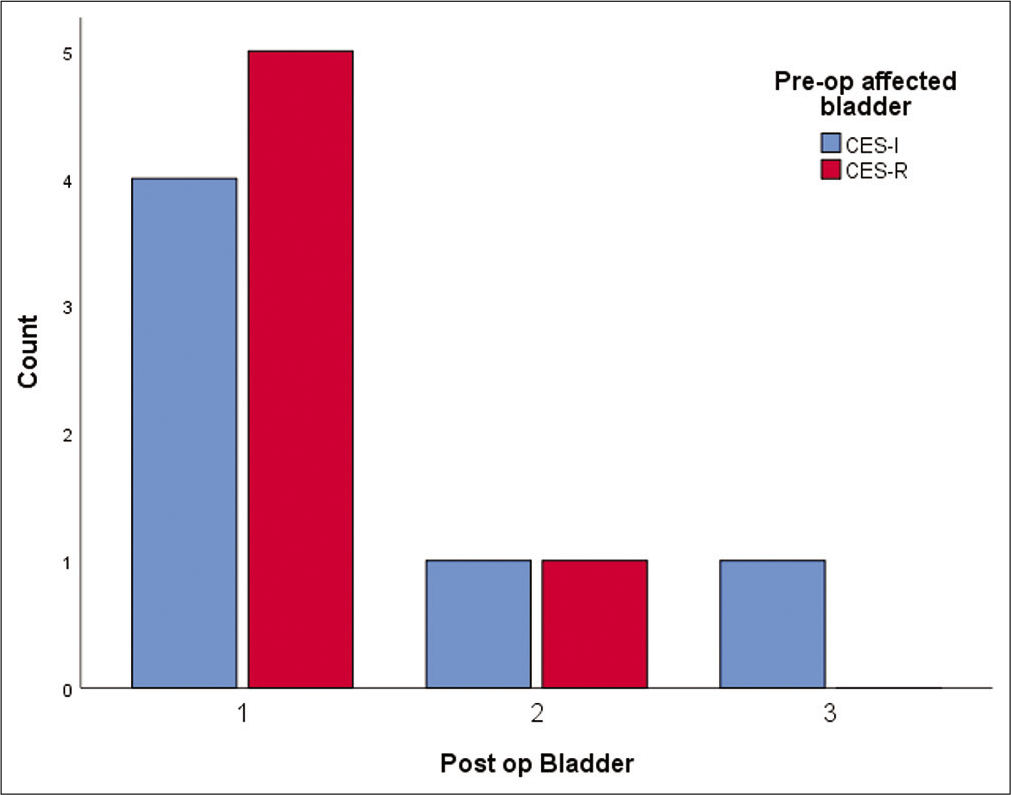

Restoration of bladder status [ Graph 2 ]

Complete restoration of bladder status was experienced in nine patients after a mean duration of 8.22 months postsurgery (ranging from 2 to 15 months). Two patients had persistent symptoms and continued on self-intermittent catheterization while one patient had some residual symptoms like urgency but was able to self-void with some difficulty. These two patients who persisted with symptoms had relatively longer duration of preoperative symptoms (7 and 12 months) and nearly absent perianal sensation (absent in one and 30% in other).

Graph 2:

Final bladder status with one representing completely recovered nine patients, two representing patients who failed to recover while three representing recovered patient with residual difficulty in relation to preoperative affected bladder in the form of cauda equina syndrome – incomplete and cauda equina syndrome-retention.

DISCUSSION

The presence of cauda equina syndromes with bladder and bowel symptoms in patients with lumbar disc herniation/ canal stenosis typically requires emergent surgical intervention (e.g., within 48 h to achieve the better surgical outcomes).[

Outcomes for delayed surgery for CAS (cauda equina syndrome)

Longer delays in surgery with CAS have also been analyzed. Sarvdeep et al. operated 50 cases of cauda equina syndrome with a mean delay of 12.2 days and found near total recovery in 44 patients with six patients showing partial recovery; they stressed the importance of performing decompressions in all patients irrespective of the delay.[

Delayed surgery resulting in bladder recovery

Aly et al. reported that 12 of 14 patients who presented within 1–3 months of bladder/bowel involvement with CAS regained full sphincter control; thus, they advocated surgery whether or not, it was delayed.[

CONCLUSION

We conclude that although all patients with symptoms of cauda equina syndrome should ideally be surgically decompressed within 48–72 h, as our study showed statistically significant recovery of bladder symptoms in more than 80% of patients with surgery delayed for an average of 8.2 months, delayed decompression should not be withheld.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Publication of this article was made possible by the James I. and Carolyn R. Ausman Educational Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski MS, Garrett ES, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: A meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000. 25: 1515-22

2. Aly TA, Aboramadan MO. Efficacy of delayed decompression of lumbar disk herniation causing cauda equina syndrome. Orthopedics. 2014. 37: e153-6

3. Bydon M, Lin JA, De la Garza-Ramos R, Macki M, Kosztowski T, Sciubba DM. Time to surgery and outcomes in cauda equina syndrome: An analysis of 45 cases. World Neurosurg. 2016. 87: 110-5

4. Chau AM, Xu LL, Pelzer NR, Gragnaniello C. Timing of surgical intervention in cauda equina syndrome: A systematic critical review. World Neurosurg. 2014. 81: 640-50

5. Dhatt S, Tahasildar N, Tripathy SK, Bahadur R, Dhillon M. Outcome of spinal decompression in cauda equina syndrome presenting late in developing countries: Case series of 50 cases. Eur Spine J. 2011. 20: 2235-9

6. Kalidindi KK, Sath S, Vishwakarma G, Chhabra HS. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in intervertebral disc herniation: Comparison of canal compromise and canal size in patients with and without cauda equina syndrome. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 171

7. Kostuik JP, Harrington I, Alexander D, Rand W, Evans D. Cauda equina syndrome and lumbar disc herniation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986. 68: 386-91

8. McCarthy MJ, Aylott CE, Grevitt MP, Hegarty J. Cauda equina syndrome: Factors affecting long-term functional and sphincteric outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007. 32: 207-16