- Department of Neurosurgery, Highly Specialized Hospital of National Importance “Garibaldi,” Catania, Sicily, Italy.

- Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neurosciences, School of Medicine, Postgraduate Residency Program in Neurological Surgery, Neurosurgical Clinic, AOUP “Paolo Giaccone,” Palermo, Catania, Sicily, Italy.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Cannizzaro Hospital, Catania, Sicily, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Gianluca Scalia, Department of Neurosurgery, Highly Specialized Hospital of National Importance “Garibaldi,” Catania, Sicily, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_734_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Gianluca Scalia1, Salvatore Marrone2, Roberta Costanzo2, Giuseppe Emmanuele Umana3, Carmelo Riolo1, Francesca Graziano1, Giancarlo Ponzo1, Massimiliano Giuffrida1, Massimo Furnari1, Agatino Florio1, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino2, Giovanni Federico Nicoletti1. Dural splitting reconstruction in retethering after lipomeningocele repair: Technical note. 24-Aug-2021;12:422

How to cite this URL: Gianluca Scalia1, Salvatore Marrone2, Roberta Costanzo2, Giuseppe Emmanuele Umana3, Carmelo Riolo1, Francesca Graziano1, Giancarlo Ponzo1, Massimiliano Giuffrida1, Massimo Furnari1, Agatino Florio1, Domenico Gerardo Iacopino2, Giovanni Federico Nicoletti1. Dural splitting reconstruction in retethering after lipomeningocele repair: Technical note. 24-Aug-2021;12:422. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11063/

Abstract

Background: Tethered spinal cord syndrome (TCS) can occur after the surgical repair of lipomeningoceles (LMCs). In these cases, the tethering results from postoperative adhesions between the spinal cord and the overlying repaired dura. A watertight dural closure using the residual dura and/or the surrounding tissues does not always provide enough space for the spinal cord and risks retethering. Here, we report a 16-year-old patient with secondary TCS following lipomeningocele repair who successfully underwent release of the tethered filum terminale utilizing a novel dural splitting reconstructive technique to attain a water-tight closure without the need for a duroplasty.

Methods: A 16-year-old patient had a LMC repaired at birth. She now presented with progressive low back pain, and gait disturbances. The MRI documented secondary spinal cord tethering at the prior spinal dysraphism repair site.

Results: A secondary release of the filum terminale utilizing a novel dural splitting technique to avoid the need for a duroplasty was performed.

Conclusion: Here, in a 16-year-old patient with a recurrent tethered cord syndrome following repair of a LMC at birth, we utilized a novel dural splitting reconstruction technique and averted the need for a duroplasty.

Keywords: Dura mater, Lipomeningocele, Reconstruction, Splitting, Tethered cord

INTRODUCTION

After the primary surgical repair of lipomeningoceles (LMCs), that occur in about 3-6 patients per 100.000 live births, patients can present with clinical symptoms and signs of a recurrent tethered cord (i.e., tethered cord syndrome (TCS)).[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

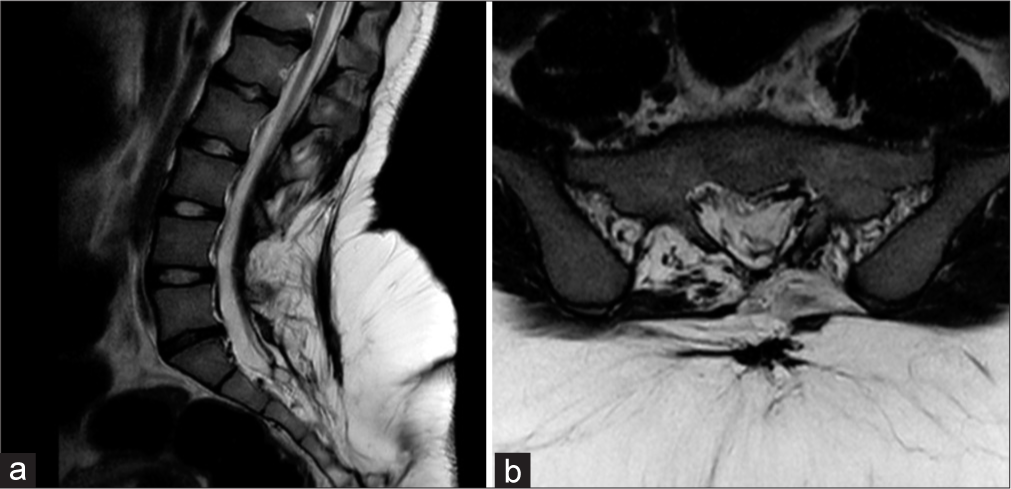

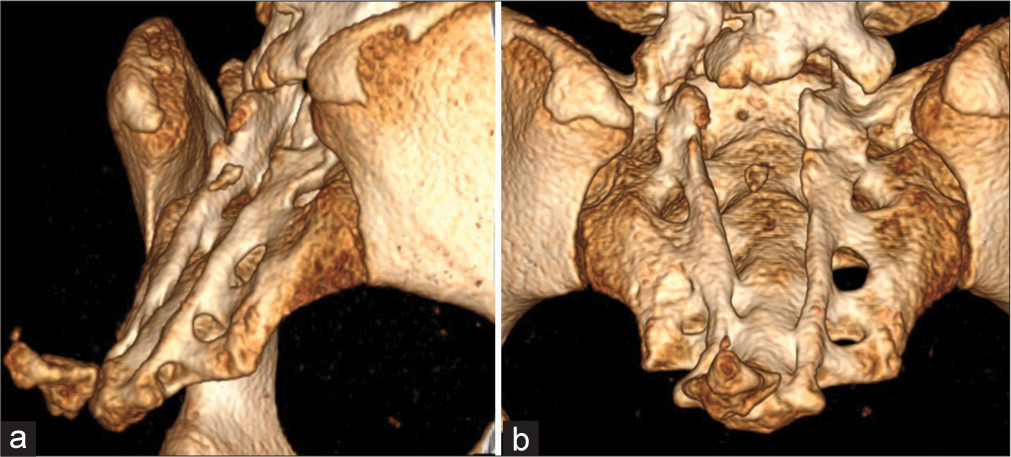

A 16-year-old female presented with progressive low back pain and right lower extremity paresthesias. Notably, although she had undergone lipomeningocele repair at 4 months of age, her only long-standing deficit (i.e., reported over 10 years) was a neurogenic bladder. The lumbosacral MR documented a residual sacro-coccygeal subcutaneous lipomatous mass, a L4-L5 tethered cord, and a S1-S2 thick filum terminale [

Technical note

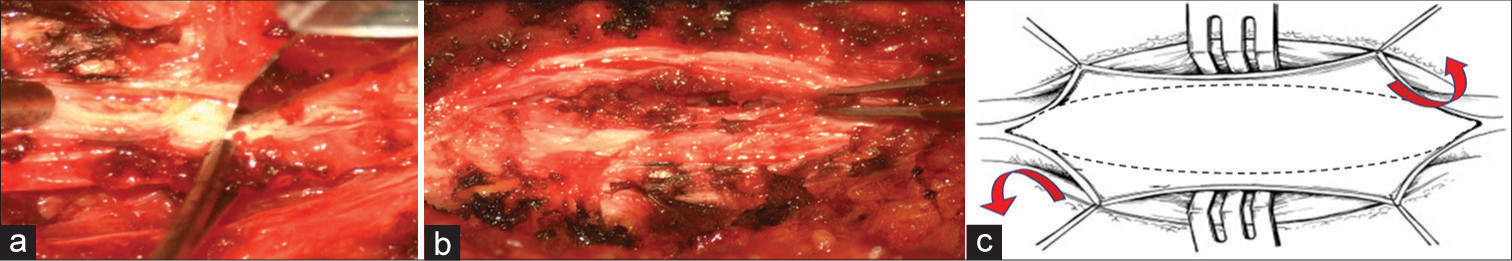

At surgery, the posterior dysraphism was easily recognized along with the associated fibroadipose tissue. Once a fibrous and hypertrophied dural sac was identified, the filum terminale was released under electrophysiological monitoring. Instead of applying a dural substitute to expand the closure, we utilized a unique “dural splitting technique (i.e., thickened, and fibrous dura on both sides was incised, splitted on the medial border, and reflected medially over the midline [

Figure 3:

Intraoperative findings showing the novel dural splitting technique. Thickened and fibrous dura on both sides was incised along the internal border (a), splitted and reflected medially over the midline using a #11 blade (b), schematic drawing illustrating dural splitting reconstruction (c).

RESULTS

The patient was able to walk without help the first postoperative day and was discharged on postoperative day 3. Six months later, the lumbosacral MRI showed no further dural adhesions or retethering.

DISCUSSION

For patients with recurrent TCS, careful dural reconstruction is warranted. This typically requires a duroplasty, to avoid retethering.[

CONCLUSION

The dural splitting reconstruction technique for watertight dural closure of a tethered cord offered an alternative to performing a duroplasty.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. French BN. The embryology of spinal dysraphism. Clin Neurosurg. 1983. 30: 295-340

2. Lee TT, Arias JM, Andrus HL, Quencer RM, Falcone SF, Green BA. Progressive posttraumatic myelomalacic myelopathy: Treatment with untethering and expansive duraplasty. J Neurosurg. 1997. 86: 624-8

3. Martínez-Lage JF, Vilar AR, Almagro MJ, del Rincón IS, de San Pedro JR, Felipe-Murcia M. Spinal cord tethering in myelomeningocele and lipomeningocele patients: The second operation. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2007. 18: 312-9

4. Ohe N, Futamura A, Kawada R, Minatsu H, Kohmura H, Hayashi K. Secondary tethered cord syndrome in spinal dysraphism. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000. 16: 457-61

5. Orlov Y, Tsimeyko O, Orlov M. Lipomeningocele in children: Current diagnosis and treatment. Ukrainian Neurosurg J. 2001. 1: 73-7

6. Reghunath A, Ghasi RG, Aggarwal A. Unveiling the tale of the tail: An illustration of spinal dysraphisms. Neurosurg Rev. 2021. 44: 97-114

7. Sakamoto H, Hakuba A, Fujitani K, Nishimura S. Surgical treatment of the retethered spinal cord after repair of lipomyelomeningocele. J Neurosurg. 1991. 74: 709-14

8. Yamada S, Zinke DE, Sanders D. Pathophysiology of. “tethered cord syndrome”. J Neurosurg. 1981. 54: 494-503