- Department of Neurosurgery, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Japanese Red Cross Ashikaga Hospital, 284-1 Yobe-cho, Ashikaga city, Tochigi,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kawasaki Municipal Hospital, 12-1 Shinkawadori, Kawasaki-ku, Kawasaki city, Kanagawa,

- Department of Radiology, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Masahiro Toda

Department of Neurosurgery, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo,

DOI:10.25259/SNI_272_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Dai Kamamoto, Tokunori Kanazawa, Eriko Ishihara, Kaoru Yanagisawa, Hideyuki Tomita, Ryo Ueda, Masahiro Jinzaki, Kazunari Yoshida, Masahiro Toda. Efficacy of a topical gelatin-thrombin hemostatic matrix, FLOSEAL®, in intracranial tumor resection. 07-Feb-2020;11:16

How to cite this URL: Dai Kamamoto, Tokunori Kanazawa, Eriko Ishihara, Kaoru Yanagisawa, Hideyuki Tomita, Ryo Ueda, Masahiro Jinzaki, Kazunari Yoshida, Masahiro Toda. Efficacy of a topical gelatin-thrombin hemostatic matrix, FLOSEAL®, in intracranial tumor resection. 07-Feb-2020;11:16. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9867/

Abstract

Background: Hemostasis plays an important role in safe brain tumor resection and also reduces the risk for surgical complications. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of FLOSEAL®, a topical hemostatic agent that contains thrombin and gelatin granules, in brain tumor resections.

Methods: We evaluated the hemostatic effect of FLOSEAL by scoring the intensity of bleeding from 1 (mild) to 4 (life threatening). We assessed the rate of success of hemostasis with 100 patients who underwent intracranial tumor resection. We also investigated the duration of the operation, the amount of intra- and postoperative bleeding, the number of hospital stays, and adverse events in patients who used FLOSEAL compared with those who did not use FLOSEAL.

Results: FLOSEAL was applied to a total of 109 bleeding areas in 100 patients. A total of 95 bleeding areas had a score of 1 and 91 (96%) showed successful hemostasis. Thirteen bleeding areas scored 2 and 8 (62%) showed hemostasis with the first application of FLOSEAL. The second application was attempted with five bleeding areas and four showed hemostasis. About 94% (103/109 areas) of bleeding points successfully achieved hemostasis by FLOSEAL. Moreover, FLOSEAL significantly decreased the amount of intraoperative bleeding and postoperative bleeding as assessed with computed tomography on 1 day postoperatively compared with no use of FLOSEAL. There were no adverse events related to FLOSEAL use.

Conclusion: Our results indicate that FLOSEAL is a reliable, convenient, and safe topical hemostatic agent for intracranial tumor resection.

Keywords: Brain tumor, FLOSEAL®, Intraoperative hemorrhage, Postoperative hematoma, Topical gelatin- thrombin hemostatic matrix

INTRODUCTION

In neurosurgical operations, most procedures involve a relatively limited space, especially in microscopic or endoscopic operations. Continuous bleeding easily obstructs the operative view in such operations, and this makes identifying the point of bleeding, which may cause damage to surrounding tissue with hemostasis, more difficult for surgeons. In neurosurgical operations, hemostasis is essential for a clear operative field for safe resection.[

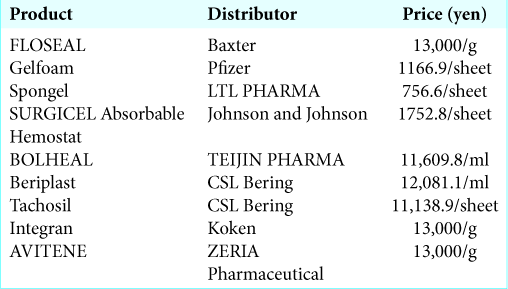

In the past century, many hemostatic agents were introduced to improve the operation, such as bone wax, absorbable gelatin compressed sponges, oxidized regenerated cellulose, microfibrillar collagen hemostat, and fibrin glue. Recently, a novel hemostatic agent, FLOSEAL®, was introduced with Food and Drug Administration approval in 1999 and was included in insurance in Japan in August 2014. FLOSEAL is a topic hemostatic agent that contains thrombin and bovine- derived gelatin granules.[

Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the effect of FLOSEAL by scoring bleeding before applying FLOSEAL after removal of brain tumors with operative videos and assessed the rate of successful hemostasis. In addition, with postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan images, we evaluated the amount of the postoperative bleeding and compared it with cases without FLOSEAL use. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of FLOSEAL objectively in brain tumor resection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We evaluated 100 patients who underwent tumor resection by either craniotomy or an endonasal endoscopic operation. We included patients at the Department of Neurosurgery, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan, the Department of Neurosurgery, Japanese Red Cross Ashikaga Hospital, Tochigi, Japan, and the Department of Neurosurgery, Kawasaki Municipal Hospital, Kanagawa, Japan, between August 2017 and September 2018. Patients who fulfilled the following criteria were included in the study: (1) FLOSEAL (Baxter International Inc., IL, USA) was used in the operation for hemostasis after tumor resection; (2) FLOSEAL was washed out in 10 min after its application; and (3) preoperative written informed consent was obtained. This group of patients comprised the FLOSEAL group. Clinical information, including pre- and postoperative images, operative time, amount of intraoperative bleeding, all events that occurred in hospital, blood collection data, and additional treatment, were obtained from the patients’ medical records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Keio University School of Medicine and called “Evaluation of effectiveness of FLOSEAL® in brain tumor surgery” (Approval number: 20160439).

For a comparison group, we evaluated 100 patients who underwent tumor resection, by either craniotomy or an endonasal endoscopic operation at the Department of Neurosurgery, Keio University School of Medicine between April 2013 and May 2014, before FLOSEAL received insurance approval in Japan. This group of patients comprised the non-FLOSEAL group.

Validation of intraoperative bleeding severity scale

We evaluated the severity of intraoperative bleeding using a scale that has been described previously.[

The scores were initially determined just before FLOSEAL was applied after removal of the tumor. We then evaluated whether hemostasis was successful after FLOSEAL was washed by irrigation for each FLOSEAL application. This scoring and evaluation were performed for every FLOSEAL application [

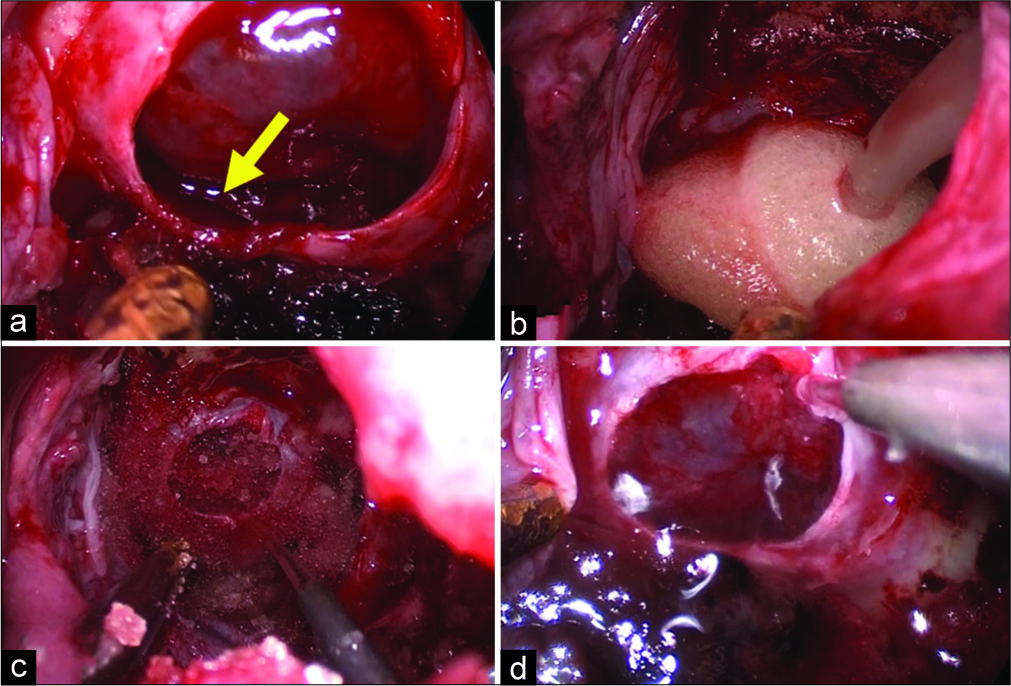

Figure 1:

Hemostasis using FLOSEAL. A patient with pituitary adenoma underwent resection through endonasal endoscopic approach. (a) Moderate bleeding was observed from the cavernous sinus after tumor removal (yellow arrow), (b) FLOSEAL was applied to the bleeding, (c) FLOSEAL was washed by saline 2 min after its application, (d) complete hemostasis was achieved.

Evaluation of the severity of intraoperative bleeding was performed by a neurosurgeon (E.I.) with an operative video and then another neurosurgeon (D.K.) confirmed the score.

Evaluation of postoperative bleeding

Postoperative bleeding in CT scan images with 5 mm in thickness taken at postoperative day (POD) 1 was analyzed by a three-dimensional system volume analyzer, SYNAPSE VINCENT (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), and the volume of the bleeding was calculated. In these images, subdural hemorrhage or hemorrhage in the excised cavity, which was the target for hemostasis of FLOSEAL, was evaluated. Extradural hemorrhage, where FLOSEAL is not adapted, was excluded from this measurement.

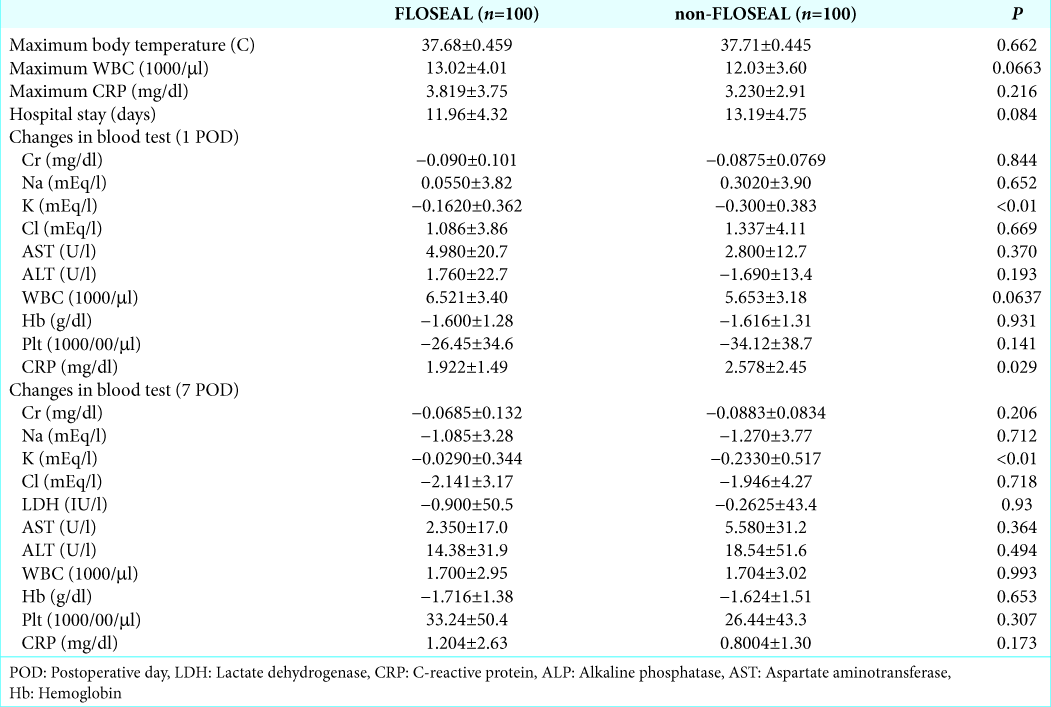

Changes in blood data, adverse events, and hospital stay

In general, at our institute, we check blood data at PODs 1 and 7. Therefore, for postoperative blood collection data, we evaluated changes in the values of each factor compared with the initial data in each group. FLOSEAL may cause infection, thrombosis, or postoperative hemorrhage, leading to postoperative anemia. Therefore, we evaluated maximum body temperature during the hospital stay, maximum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and the number of white blood cells (WBCs). In addition, we evaluated the number of days for hospital stay after the operations.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by the JMP program (version 12.0.1; SAS Institute Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All continuous data, such as age, tumor size, blood collection data, operative time, intraoperative hemorrhage, body temperature, hospital stay, and the amount of postoperative bleeding, were analyzed by t-tests between the FLOSEAL group and non-FLOSEAL group. For other data, such as sex, diagnosis, approach (open, microsurgery, or combined surgery), and the recurrence rate, were analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test.

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline patients’ characteristics

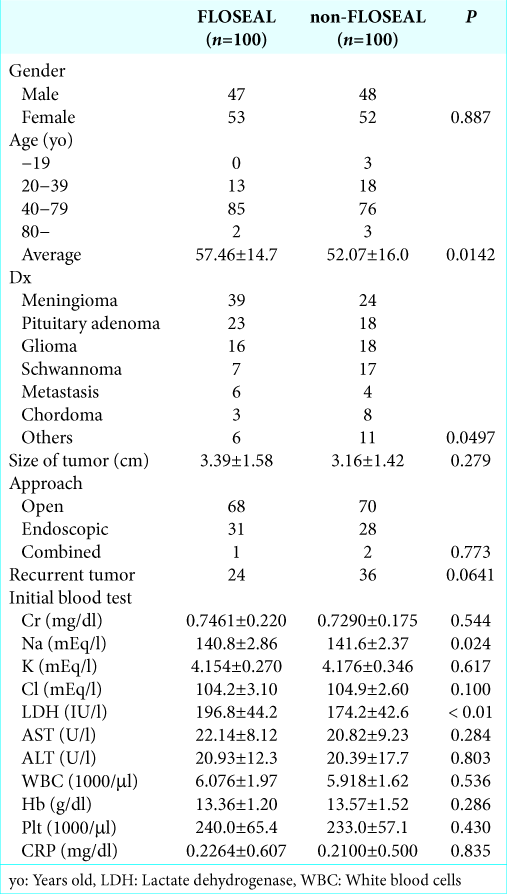

The patients’ characteristics are listed in

In the initial blood test, sodium levels were lower and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were higher in the FLOSEAL group compared with the non-FLOSEAL group (P = 0.024 and P < 0.01, respectively), but mean values in both groups were within the normal range. There were no significant differences in any other factors between the groups.

Severity of intraoperative bleeding before hemostasis and the success rate

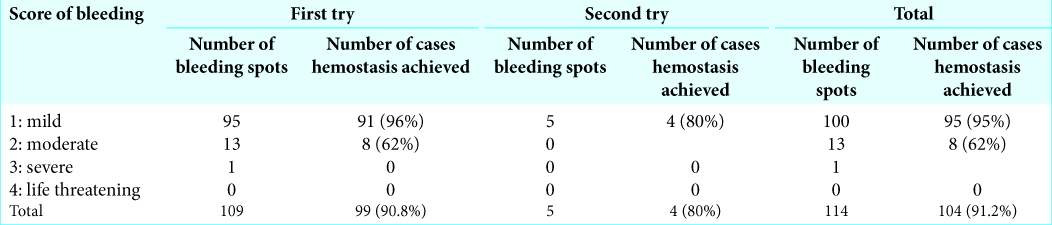

The severity of bleeding before the application of FLOSEAL and the success rate is shown in

Operative time and intra- and postoperative bleeding

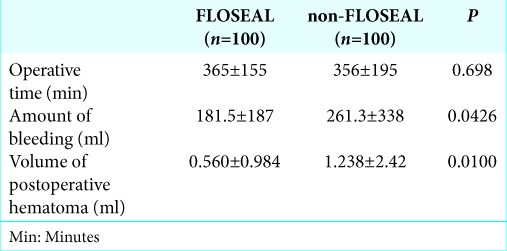

The duration of the operation and amount of intra- and postoperative bleeding in the FLOSEAL and non-FLOSEAL groups are shown in

Changes in blood collection data, adverse events, and hospital stay

Blood collection data, adverse events, and hospital stay are shown in

With regard to postoperative infection, there were no significant differences in maximum body temperature after the operation, maximum CRP levels, and WBC count between the groups. CRP levels at POD 1 were significantly higher in the non-FLOSEAL group than in the FLOSEAL group (P = 0.029). There were no adverse events directly affected by FLOSEAL, although an operation for hematoma removal was performed in the non-FLOSEAL group for postoperative hemorrhage.

There was no significant difference in the hospital stay between the FLOSEAL and non-FLOSEAL groups.

DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of FLOSEAL, which is a topical hemostatic agent containing a flowable gelatin bovine matrix and a human-derived thrombin component, has been shown in various types of operations[

In our cohort, with the first FLOSEAL application, 91% of cases showed successful hemostasis. Although most of the intensity of bleeding was mild (95/109 bleeding spots), this success rate is similar to the previous reports.[

The FLOSEAL group had less blood loss during the operation and less postoperative bleeding compared with the non-FLOSEAL group. A reduction in intraoperative bleeding by FLOSEAL has been reported in various fields of operations,[

Perioperative bleeding increases morbidity, mortality, and medical costs.[

FLOSEAL application can cause infection, inflammation, and anemia. In our cohort, except for the finding that CRP levels at POD 1 were higher in the non-FLOSEAL group than in the non-FLOSEAL group, there was no significant difference in blood collection data or body temperature. Additional adverse events related to FLOSEAL were not observed.

In the present study, FLOSEAL provided reliable, convenient, and safe hemostasis in intracranial tumor resection, especially at a limited operative field. FLOSEAL should be added as an option for hemostasis when traditional methods fail to achieve hemostasis.

CONCLUSION

This study showed a high rate (91%) of hemostasis using FLOSEAL after intracranial tumor resection. In addition, FLOSEAL use reduced the amount of postoperative bleeding and there were no adverse events related to FLOSEAL. Our results indicate that FLOSEAL is a reliable, convenient, and safe topical hemostatic agent in intracranial tumor resection.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

We received a research grant from Baxter International Inc., but this company was not involved in this study.

References

1. Cappabianca P, Esposito F, Esposito I, Cavallo LM, Leone CA. Use of a thrombin-gelatin haemostatic matrix in endoscopic endonasal extended approaches: Technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2009. 151: 69-77

2. D’Andrilli A, Cavaliere I, Maurizi G, Andreetti C, Ciccone AM, Ibrahim M. Evaluation of the efficacy of a haemostatic matrix for control of intraoperative and postoperative bleeding in major lung surgery: A prospective randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015. 48: 679-83

3. Docimo G, Tolone S, Conzo G, Limongelli P, Del Genio G, Parmeggiani D. A gelatin-thrombin matrix topical hemostatic agent (FLOSEAL) in combination with harmonic scalpel is effective in patients undergoing total thyroidectomy: A prospective, multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Surg Innov. 2016. 23: 23-9

4. Durrani OM, Fernando AI, Reuser TQ. Use of a novel topical hemostatic sealant in lacrimal surgery: A prospective, comparative study. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007. 23: 25-7

5. Esposito F, Cappabianca P, Angileri FF, Cavallo LM, Priola SM, Crimi S. Gelatin-thrombin hemostatic matrix in neurosurgical procedures: Hemostasis effectiveness and economic value of clinical and surgical procedure-related benefits. J Neurosurg Sci. 2016. p.

6. Fiss I, Danne M, Stendel R. Use of gelatin-thrombin matrix hemostatic sealant in cranial neurosurgery. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2007. 47: 462-7

7. Gazzeri R, Galarza M, Conti C, De Bonis C. Incidence of thromboembolic events after use of gelatin-thrombin-based hemostatic matrix during intracranial tumor surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2018. 41: 303-10

8. Goldstein DJ, Seldomridge JA, Chen JM, Catanese KA, DeRosa CM, Weinberg AD. Use of aprotinin in LVAD recipients reduces blood loss, blood use, and perioperative mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995. 59: 1063-7

9. Jo SH, Mathiasen RA, Gurushanthaiah D. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of a hemostatic sealant in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007. 137: 454-8

10. Lewis KM, Li Q, Jones DS, Corrales JD, Du H, Spiess PE. Development and validation of an intraoperative bleeding severity scale for use in clinical studies of hemostatic agents. Surgery. 2017. 161: 771-81

11. Li QY, Lee O, Han HS, Kim GU, Lee CK, Kang SS. Efficacy of a topical gelatin-thrombin matrix sealant in reducing postoperative drainage following anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Asian Spine J. 2015. 9: 909-15

12. Makhija D, Rock M, Ikeme S, Kuntze E, Epstein JD, Nicholson G. Cost-consequence analysis of two different active flowable hemostatic matrices in spine surgery patients. J Med Econ. 2017. 20: 606-13

13. Martorana E, Ghaith A, Micali S, Pirola GM, De Carne C, Fidanza F. A retrospective analysis of the hemostatic effect of FLOSEAL in patients undergoing robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urol Int. 2016. 96: 274-9

14. Nasso G, Piancone F, Bonifazi R, Romano V, Visicchio G, De Filippo CM. Prospective, randomized clinical trial of the FLOSEAL matrix sealant in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009. 88: 1520-6

15. Oz MC, Rondinone JF, Shargill NS. FLOSEAL matrix: New generation topical hemostatic sealant. J Card Surg. 2003. 18: 486-93

16. Raga F, Sanz-Cortes M, Bonilla F, Casañ EM, Bonilla-Musoles F. Reducing blood loss at myomectomy with use of a gelatin-thrombin matrix hemostatic sealant. Fertil Steril. 2009. 92: 356-60

17. Ramirez MG, Deutsch H, Khanna N, Cheatem D, Yang D, Kuntze E. FLOSEAL only versus in combination in spine surgery: A comparative, retrospective hospital database evaluation of clinical and healthcare resource outcomes. Hosp Pract (1995). 2018. 46: 189-96

18. Ramirez MG, Niu X, Epstein J, Yang D. Cost-consequence analysis of a hemostatic matrix alone or in combination for spine surgery patients. J Med Econ. 2018. 21: 1041-6

19. Sabel M, Stummer W. The use of local agents: Surgicel and surgifoam. Haemost Spine Surg. 2005. 13: 103-7

20. Safaee M, Sun MZ, Oh T, Aghi MK, Berger MS, McDermott MW. Use of thrombin-based hemostatic matrix during meningioma resection: A potential risk factor for perioperative thromboembolic events. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014. 119: 116-20

21. Stokes ME, Ye X, Shah M, Mercaldi K, Reynolds MW, Rupnow MF. Impact of bleeding-related complications and/or blood product transfusions on hospital costs in inpatient surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011. 11: 135-

22. Tackett SM, Sugarman R, Kreuwel HT, Alvarez P, Nasso G. Hospital economic impact from hemostatic matrix usage in cardiac surgery. J Med Econ. 2014. 17: 670-6

23. Velyvis JH. Gelatin matrix use reduces postoperative bleeding after total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2015. 38: e118-23

24. Yao HH, Hong MK, Drummond KJ. Haemostasis in neurosurgery: What is the evidence for gelatin-thrombin matrix sealant?. J Clin Neurosci. 2013. 20: 349-56