- Department of Neurosurgery, International University of Health and Welfare, Narita Hospital, Narita City, Chiba, Japan,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Baba Memorial Hospital, Sakai City, Osaka, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_176_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Yuhei Michiwaki1,2, Naoki Maehara2, Nice Ren2, Yosuke Kawano2, Shintaro Nagaoka2, Kazushi Maeda2, Yukihide Kanemeto2, Hidefuku Gi2. Indications for computed tomography use and frequency of traumatic abnormalities based on real-world data of 2405 pediatric patients with minor head trauma. 28-Jun-2021;12:321

How to cite this URL: Yuhei Michiwaki1,2, Naoki Maehara2, Nice Ren2, Yosuke Kawano2, Shintaro Nagaoka2, Kazushi Maeda2, Yukihide Kanemeto2, Hidefuku Gi2. Indications for computed tomography use and frequency of traumatic abnormalities based on real-world data of 2405 pediatric patients with minor head trauma. 28-Jun-2021;12:321. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10914/

Abstract

Background: In pediatric patients with minor head trauma, computed tomography (CT) is often performed beyond the scope of recommendations that are based on existing algorithms. Herein, we evaluated pediatric patients with minor head trauma who underwent CT examinations, quantified its frequency, and determined how often traumatic findings were observed in the intracranial region or skull.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and neuroimages of pediatric patients (0–5 years) who presented at our hospital with minor head trauma within 24 h after injury.

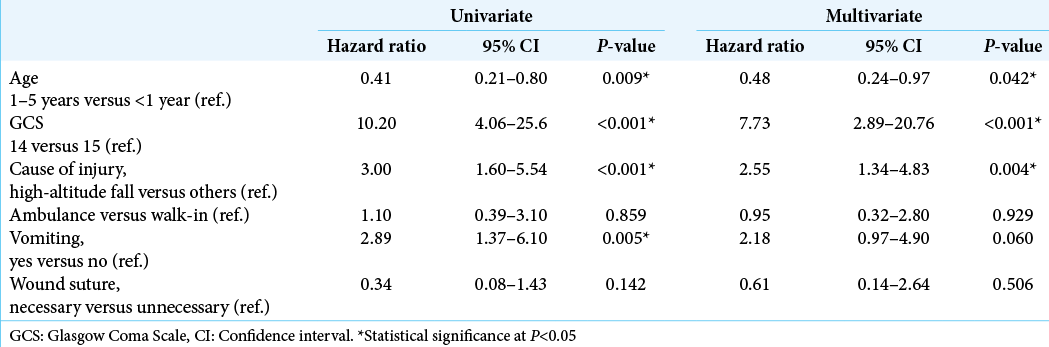

Results: Of 2405 eligible patients, 1592 (66.2%) underwent CT examinations and 45 (1.9%) had traumatic intracranial hemorrhage or skull fracture on CT. No patient underwent surgery or intensive treatment. Multivariate analyses revealed that an age of 1–5 years (vs. P P = 0.008), sustaining a high-altitude fall (P P P P = 0.042), GCS score of 14 (P P = 0.004).

Conclusion: Although slightly broader indications for CT use, compared to the previous algorithms, could detect and evaluate minor traumatic changes in pediatric patients with minor head trauma, over-indications for CT examinations to detect only approximately 2% of abnormalities should be avoided and the indications should be determined based on the patient’s age, condition, and cause of injury.

Keywords: Computed tomography, Intracranial hemorrhage, Minor head trauma, Pediatric patients, Skull fracture

INTRODUCTION

Children with minor head trauma commonly present to the emergency department.[

Thus, the aims of this study were to (1) evaluate the frequency of CT examinations; (2) identify demographic, historic, and diagnostic trends among pediatric patients with minor head trauma who received a CT examination; and (3) determine how often traumatic abnormalities occurred in the intracranial region or skull.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and neuroimages of pediatric patients (0–5-years-old) who presented to our hospital for minor head trauma within 24 h after head injury between January 2017 and February 2020. Excluded patients were those admitted for more than 24 h following an injury, those who were older than 5 years, and those with insufficient documentation in their medical records. Specifically analyzed parameters were age, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, the cause of injury, use of ambulance services, assessment with CT, traumatic abnormalities shown on CT, vomiting, and the necessity for wound sutures. As the participants were 0–5 years of age, the medical history of headache or loss of consciousness at the time of injury was often unclear; therefore, these data were not included in our analyses.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate putative prognostic factors in terms of the frequency of CT examinations and associated traumatic abnormalities. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. JMP Pro (version 13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

The present study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The Institutional Review Board of our institution approved the present study and waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective study design.

RESULTS

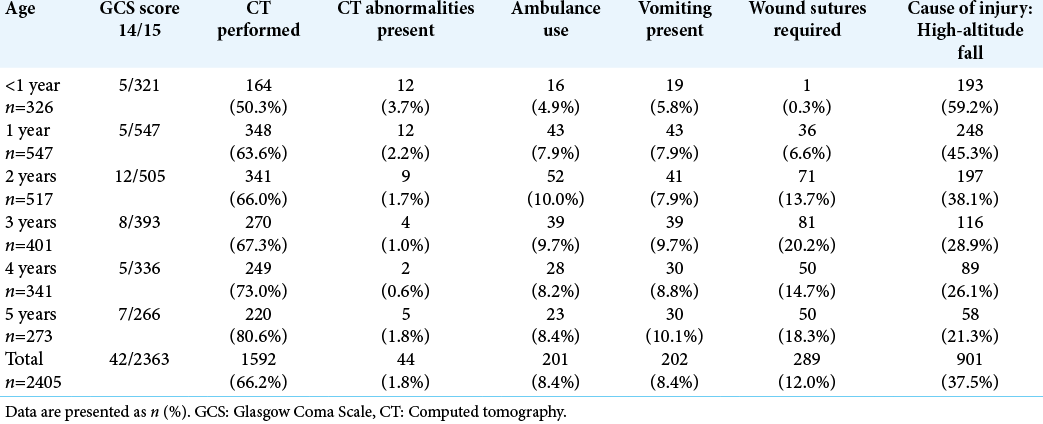

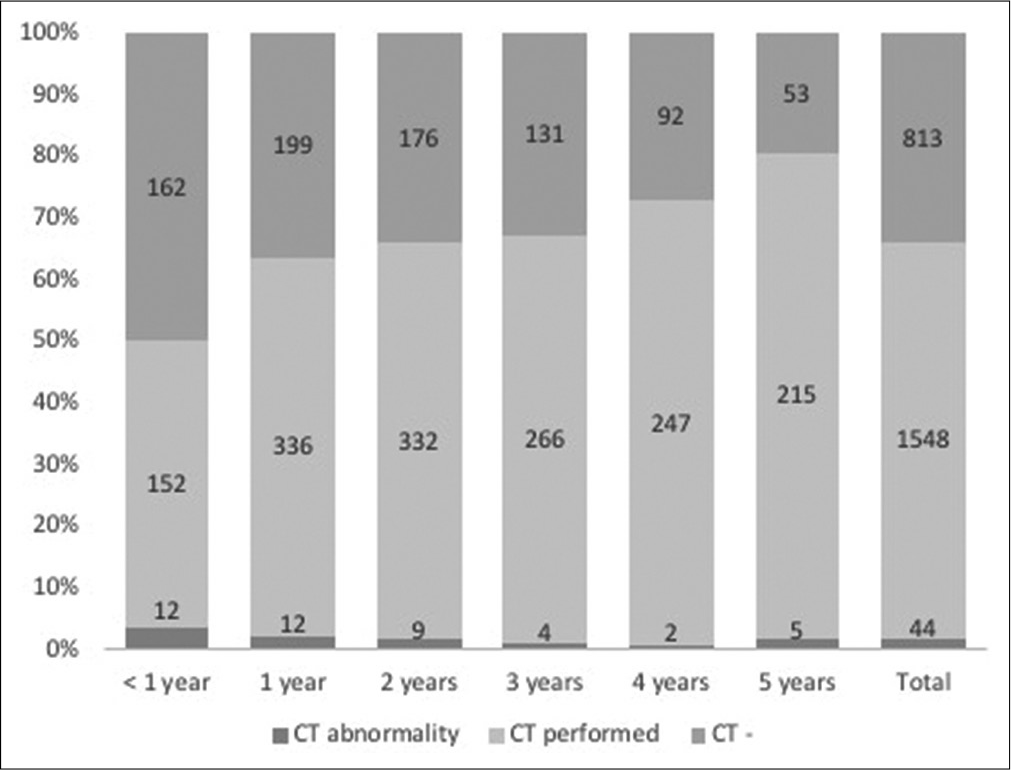

A total of 2405 pediatric patients were eligible for the present study. These patients’ characteristics are summarized in [

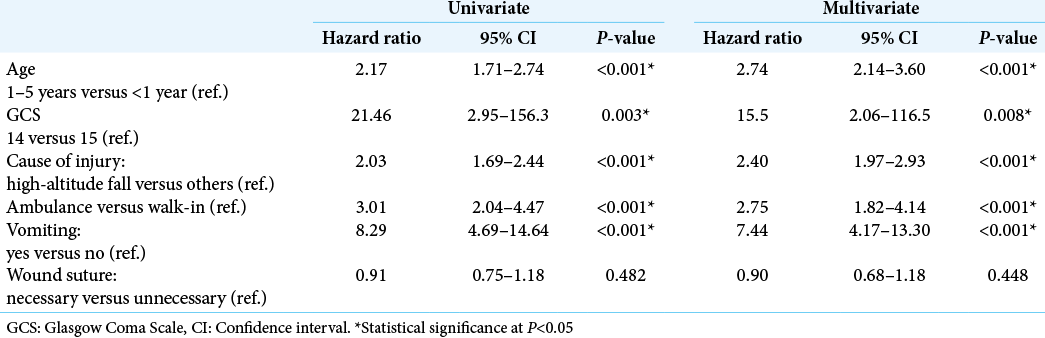

Next, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses to better understand when to perform CT examinations [

CT examinations for minor head trauma rarely reveal brain abnormalities unrelated to the trauma. Of the 1592 patients who underwent CT examinations in the present study, 26 cases presented with an arachnoid cyst and two presented with ventricle enlargement; however, none required treatment. No brain tumors or cerebrovascular diseases were observed on the CT scans.

DISCUSSION

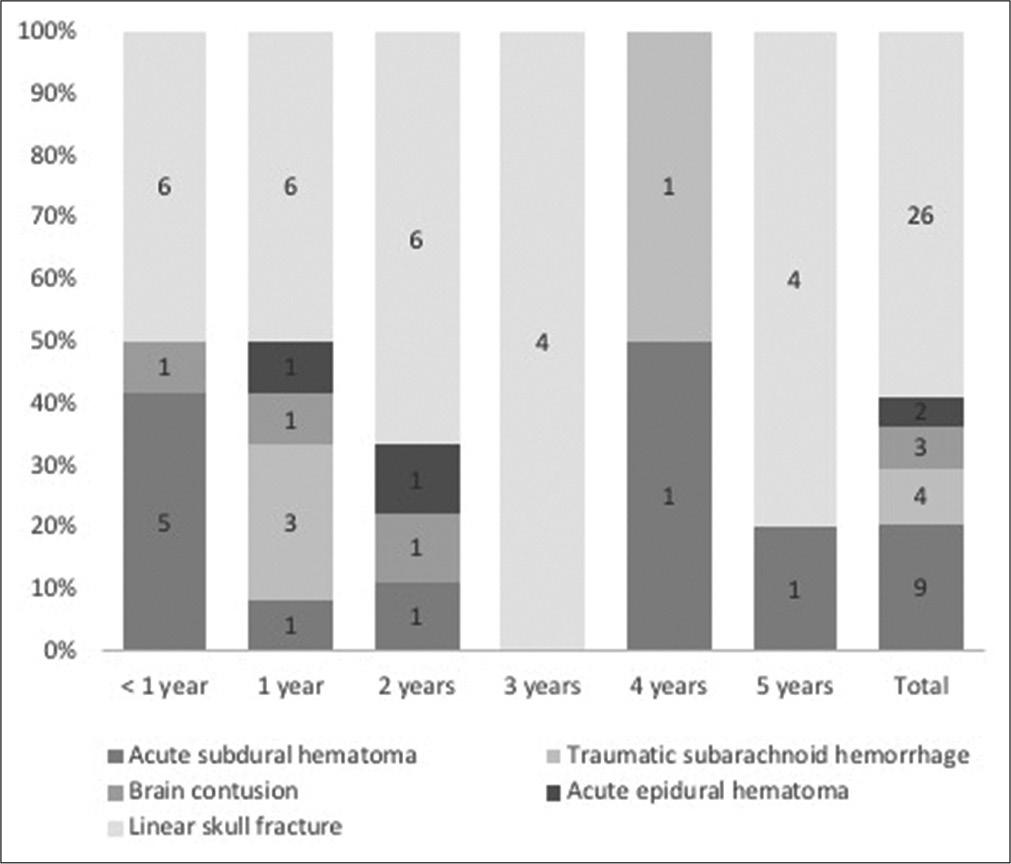

The present study involved a large sample of 2405 pediatric patients with minor head trauma and revealed that CT examinations were performed in 1592 (66%) patients; and 45 (1.9%) patients presented with traumatic intracranial hemorrhage or skull fracture. CT was most commonly performed in patients aged 1–5 years with unusual neurological symptoms and in severe cause of injury which was defined as a high-altitude fall. Moreover, traumatic abnormalities on CT were observed in patients <1 year of age, with a GCS score of 14, and whose cause of injury was a high-altitude fall. The results of this study provide important suggestions on the indications for CT use and assessment in pediatric patients with minor head trauma.

It has been recommended in the literature to avoid radiological examinations in children, unless necessary, because of the increased risk of developing brain tumors, leukemia, and malignancies as a result of radiation exposure. [

In the present study, patients who were 1–5-years-old, had a GCS score of 14, experienced a high-altitude fall, used an ambulance, and presented with vomiting received a CT scan significantly more frequently. We suggest that these results were obtained because clinicians tended to avoid radiological examinations for patients younger than 1 year of age for the same reasons as mentioned previously. Considering that the risk of lethal malignancy associated with radiation examination is inversely proportional to the patient’s age,[

Only 0.8% and 1.1% of the patients in this study presented with intracranial hemorrhage and skull fracture, respectively; however, they were observed or were given conservative treatment and had good prognoses. These results suggest that pediatric patients with minor head trauma rarely show intracranial hemorrhage or skull fracture; however, 1–2% of the patients presented with CT abnormalities that did not require surgery or resulted in a poor prognosis. Moreover, patients with CT abnormalities typically demonstrated unusual consciousness or serious causes of injury. The previous algorithms have been primarily intended to detect patients who require surgery or intensive treatment, which excludes those with minor traumatic findings that do not require treatment.[

Study strengths and limitations

The present study is based on a large sample of pediatric patients with minor head trauma. Studies that analyze large sample sizes of patients aged 0–5 years at a single institute are very rare. The real-world data used in the present study provide important information and practical suggestions for the consultation of pediatric trauma patients. It should be noted that the scope of this study is limited by certain factors. First, since this study did not include patients with severe head trauma or severe disturbances in consciousness due to the nature of the participating hospital, this might potentially distort the facts regarding overall head trauma in pediatric patients. Moreover, as the results of this study were based on the cultural characteristics and medical system of Japan, the results may not be universally applicable. In addition, the retrospective, non-randomized, and non-blinded design of this study rendered sample size differences among the patients’ age, and potential selection biases. These factors must be considered when attempting to generalize the study results and when designing future research.

CONCLUSION

Approximately 2% of the patients in this study, aged 0–5-years-old, with minor head trauma, demonstrated traumatic intracranial hemorrhage or skull fractures on CT examination. Traumatic findings were significantly more frequent in patients younger than 1 year of age, those with a GCS score of 14, and those whose cause of injury was a high-altitude fall. Therefore, slightly broader indications for CT use could detect and evaluate minor traumatic changes in pediatric patients with minor head trauma. However, over-indications for CT use to detect only 2% of abnormalities should be avoided and the indications should be determined based on the patient’s age, condition, and cause of injury.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Blackwell CD, Gorelick M, Holmes JF, Bandyopadhyay S, Kuppermann N. Pediatric head trauma: Changes in use of computed tomography in emergency departments in the United States over time. Ann Emerg Med. 2007. 49: 320-4

2. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography-an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007. 357: 2277-84

3. Dunning J, Daly JP, Lomas JP, Lecky F, Batchelor J, Mackway-Jones K. Derivation of the children’s head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events decision rule for head injury in children. Arch Dis Child. 2006. 91: 885-91

4. Kauffman JD, Litz CN, Thiel SA, Nguyen AT, Carey A, Danielson PD. To scan or not to scan: Overutilization of computed tomography for minor head injury at a pediatric trauma center. J Surg Res. 2018. 232: 164-70

5. Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD, Atabaki SM, Holubkov R. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2009. 374: 1160-70

6. Mannix R, Meehan WP, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Computed tomography for minor head injury: Variation and trends in major United States pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2012. 160: 136-9

7. Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, Butler MW, Goergen SK, Byrnes GB. Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: Data linkage study of 11 million Australians. BMJ. 2013. 346: f2360

8. Nigrovic LE, Stack AM, Mannix RC, Lyons TW, Samnaliev M, Bachur RG. Quality improvement effort to reduce cranial CTs for children with minor blunt head trauma. Pediatrics. 2015. 136: 227-33

9. Nishijima DK, Yang Z, Urbich M, Zwienenberg-Lee M, Melnikow J, Kuppermann N. Cost-effectiveness of the PECARN rules in children with minor head trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2015. 65: 72-80

10. Osmond MH, Klassen TP, Wells GA, Correll R, Jarvis A, Joubert G. CATCH: A clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ. 2010. 182: 341-8

11. Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, McHugh K, Lee C, Kim KP. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012. 380: 499-505

12. Shapiro K, Smith LP, Cooper PR.editors. Special considerations for the pediatric age group. Head Injury. Maryland: William and Wilkins; 1993. p. 427-57

13. Smits M, Dippel DW, Nederkoorn PJ, Dekker HM, Vos PE, Kool DR. Minor head injury: CT-based strategies for management-a cost-effectiveness analysis. Radiology. 2010. 254: 532-40

14. Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L. Traumatic brain injury-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths-United States, 2007 and 2013, MMWR. Surveill Summ. 2017. 66: 1-16

15. . The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) concept in pediatric CT intelligent dose reduction. Pediatr Radiol. 2002. 32: 219-20