- Department of Neurosurgery, Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration, Warsaw, Wołoska, Poland.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_140_2019

Copyright: © 2019 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Kacper Kostyra, Bogusław Kostkiewicz. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit and frontal sinus of the adult woman: A first case report in Poland. 29-Nov-2019;10:234

How to cite this URL: Kacper Kostyra, Bogusław Kostkiewicz. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit and frontal sinus of the adult woman: A first case report in Poland. 29-Nov-2019;10:234. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9774/

Abstract

Background: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a term describing a clonal proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells (histiocytes), which may manifest as unisystem (unifocal or multifocal) or multisystem disease. LCH is a rare cause of the orbital tumor with the predilection to its lateral wall which is particularly common in children.

Case Description: We report an unusual case of a 33-year-old woman, 6 months after childbirth, who presented with the edema of the right orbit and upper eyelid with headaches. On physical examination, the patient had a right superior and lateral swelling of the eyelid and the orbit and right enophthalmos, without blurred vision. Magnetic resonance imaging showed well-defined, expansile, intensely homogeneously enhancing mass lesion in the right superolateral orbital rim with the destruction of the upper wall of the orbit, growing into the frontal sinus and frontal part of the cranium with the bold of the dura mater in this region. Radical excision of the tumor was achieved through a right fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic craniotomy. Histopathological examination had confirmed the diagnosis of the LCH. The patient was discharged home with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0.

Conclusion: The main purpose of this case report is that LCH should be considered as one of the possible causes of quickly appearing tumor of the orbit in adults.

Keywords: Histiocytosis X, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Orbital tumor

INTRODUCTION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a term describing a clonal proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells (histiocytes), which may manifest as unisystem (unifocal or multifocal) or multisystem disease. LCH is a rare cause of the orbital tumor with the predilection to its lateral wall which is particularly common in children.

CASE DESCRIPTION

We report an unusual case of 33-year-old woman, without chronic diseases, 6 months after childbirth, who was admitted to our clinic because of the edema of the right orbit and upper eyelid with headaches of 1-month duration. On physical examination, the patient had a right superior and lateral swelling of the eyelid and the orbit and right enophthalmos, without blurred vision.

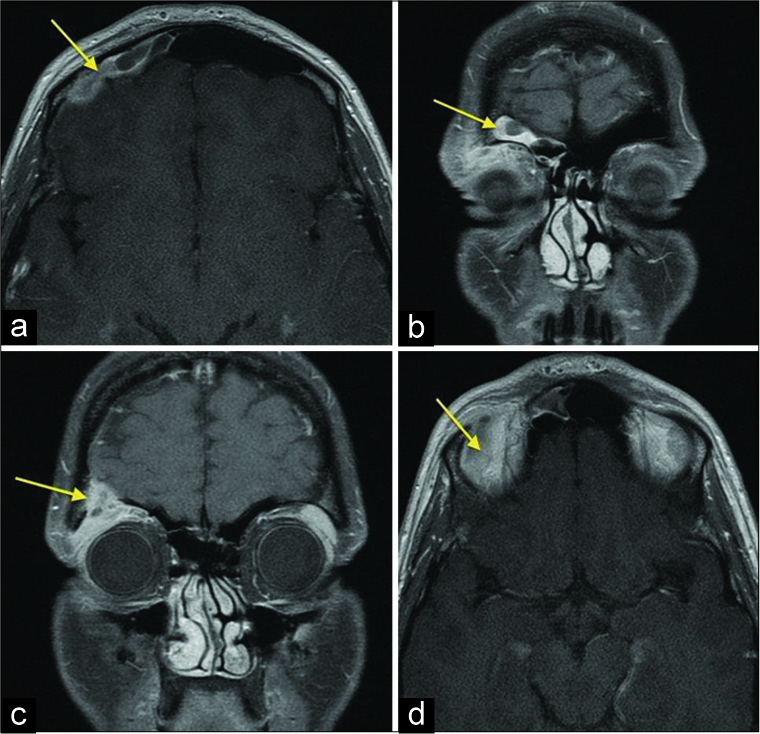

On admission, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed well-defined, expansile, intensely homogeneously enhancing mass lesion in the right superolateral orbital rim with destruction of the upper wall of the orbit, growing into the frontal part of the cranium with the bold of the dura mater in this region [

Radical excision of the tumor was achieved through a right fronto-temporo-orbito-zygomatic craniotomy.

On histopathology, sheets of histiocytic cells with indented pale nuclei with nuclear grooves suggestive of LCH were seen. Positive immunohistochemical staining for S-100, CD1a, and CD68 confirmed the diagnosis. Ki67 was about 30%.

The whole-body scintigraphy showed the increased collection of the tag in the region of the right orbit, but the postoperative MRI showed no features of the recurrence. We do not decide to use the radio- or chemotherapy in this case. One year after treatment, there is still no recurrence, yet.

DISCUSSION

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), previously called histiocytosis X, is a term describing a clonal proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells that may manifest as unisystem (unifocal or multifocal) or multisystem disease.[

Histopathologically, the histiocytic infiltrate consists – despite its relatively benign-looking histologic features – predominantly of a clonal proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells that resemble tissue macrophages rather than the typical dendritic shape of Langerhans cells in the skin.[

LCH is classified into four groups based on a clinical staging system, i.e., Group A – bone only or bone and contiguous soft-tissue involvement, Group B – skin or other squamous mucous membranes only or with involvement of related superficial lymph nodes, Group C – soft tissue and viscera only, and Group D – multisystem disease.[

The ocular manifestation of the LCH usually occurs in children but may also affect adults.[

Diagnostic imaging, including computed tomography and magnetic resonance tomography, shows well-defined bony lesions with a classic “punched-out” lytic appearance that are often accompanied by soft-tissue involvement in the orbit.[

There is still no recurrence in our case, but it can appear in patients with localized orbital lesions within even 13 to 16 years after the initial treatment (most common within 12–18 months).[

As the pathogenesis of LCH is still unknown, treatment is empirical and depends on the disease severity and degree of systemic involvement. In general, the diagnosis of LCH should be proven by a biopsy. Incisional and excisional biopsies are preferred over fine-needle aspiration biopsy because the latter might not provide enough material for a sufficient histologic diagnosis.[

CONCLUSION

The main purpose of this case report is that LCH should be considered as one of the possible causes of quickly appearing tumor of the orbit in adults. Moreover, an early diagnosis and multidisciplinary approach are required for proper staging of the disease to plan the best management of each case as treatment varies from case to case.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Aricò M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the international registry of the histiocyte society. Eur J Cancer. 2003. 39: 2341-8

2. Escardó-Paton JA, Neal J, Lane CM. Late recurrence of langerhans cell histiocytosis in the orbit. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004. 88: 838-9

3. Favara BE, Jaffe R. Pathology of langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1987. 1: 75-97

4. Favara BE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: An identity crisis. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001. 37: 545-

5. Gündüz K, Palamar M, Parmak N, Kuzu I. Eosinophilic granuloma of the orbit: Report of two cases. J AAPOS. 2007. 11: 506-8

6. Hamre M, Hedberg J, Buckley J, Bhatia S, Finlay J, Meadows A. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: An exploratory epidemiologic study of 177 cases. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997. 28: 92-7

7. Harris GJ, Woo KI. Eosinophilic granuloma of the orbit: A paradox of aggressive destruction responsive to minimal intervention. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2003. 101: 93-103

8. Herwig MC, Wojno T, Zhang Q, Grossniklaus HE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit: Five clinicopathologic cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013. 58: 330-40

9. Kilpatrick SE, Wenger DE, Gilchrist GS, Shives TC, Wollan PC, Unni KK. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X) of bone. A clinicopathologic analysis of 263 pediatric and adult cases. Cancer. 1995. 76: 2471-84

10. Laman JD, Leenen PJ, Annels NE, Hogendoorn PC, Egeler RM. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. “insight into DC biology”. Trends Immunol. 2003. 24: 190-6

11. Levy J, Monos T, Kapelushnik J, Maor E, Nash M, Lifshitz T. Ophthalmic manifestations in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004. 6: 553-5

12. Maccheron LJ, McNab AA, Elder J, Selva D, Martin FJ, Clement CI. Ocular adnexal langerhans cell histiocytosis clinical features and management. Orbit. 2006. 25: 169-77

13. Margo CE, Goldman DR. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008. 53: 332-58

14. Pinkus GS, Lones MA, Matsumura F, Yamashiro S, Said JW, Pinkus JL. Langerhans cell histiocytosis immunohistochemical expression of fascin, a dendritic cell marker. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002. 118: 335-43

15. Risdall RJ, Dehner LP, Duray P, Kobrinsky N, Robison L, Nesbit ME. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis). Prognostic role of histopathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1983. 107: 59-63

16. Senechal B, Elain G, Jeziorski E, Grondin V, Patey-Mariaud de Serre N, Jaubert F. Expansion of regulatory T cells in patients with langerhans cell histiocytosis. PLoS Med. 2007. 4: e253-

17. Shetty SB, Mehta C. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2001. 49: 267-8

18. Song A, Johnson TE, Dubovy SR, Toledano S. Treatment of recurrent eosinophilic granuloma with systemic therapy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 19: 140-4

19. Willman CL, Busque L, Griffith BB, Favara BE, McClain KL, Duncan MH. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X) a clonal proliferative disease. N Engl J Med. 1994. 331: 154-60

20. Willman CL. Detection of clonal histiocytes in langerhans cell histiocytosis: Biology and clinical significance. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1994. 23: S29-33

21. Wladis EJ, Tomaszewski JE, Gausas RE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the orbit 10 years after involvement at other sites. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008. 24: 142-3

22. Woo KI, Harris GJ. Eosinophilic granuloma of the orbit: Understanding the paradox of aggressive destruction responsive to minimal intervention. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 19: 429-39

23. Yu RC, Chu C, Buluwela L, Chu AC. Clonal proliferation of langerhans cells in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Lancet. 1994. 343: 767-8

24. Zausinger S, Müller A, Bise K, Klauss V. Eosinophilic granuloma of the orbit in an adult woman. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000. 142: 215-7

25. Zelger B. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A reactive or neoplastic disorder?. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001. 37: 543-4