- Department of Neurosurgery, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Maya Alexis, Department of Neurosurgery, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_70_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Maya Alexis, Rachel Blue, Jang W. Yoon. Multi-layer approach to complex traumatic anterior skull base fracture repair: A case report. 07-Apr-2023;14:126

How to cite this URL: Maya Alexis, Rachel Blue, Jang W. Yoon. Multi-layer approach to complex traumatic anterior skull base fracture repair: A case report. 07-Apr-2023;14:126. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12243/

Abstract

Background: Anterior skull base fractures represent a unique challenge for neurosurgical repair due to the potential for orbital injury and the proximity to the air sinuses, yielding increased possibility for infection, and persistent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. While multiple techniques are available for the repair of anterior skull base defects, there exists a paucity of robust, long-term clinical data to guide the optimal surgical management of these fractures.

Case Description: We present the case of a complex, traumatic penetrating anterior skull base fracture, and describe a multi-layered approach for successful repair – namely, with the use of a temporally-based pericranial flap, split-thickness frontal bone graft, and autogenous abdominal fat graft. The patient was followed for nine months postoperatively, over which time she experienced no significant complications.

Conclusion: The goal of successful anterior skull base repair involves creating a durable, watertight separation between intra and extracranial compartments to prevent CSF leak, protect intracranial structures, and minimize infection risk. The temporally-based pericranial flap, split-thickness frontal bone graft, and autogenous abdominal fat graft represent safe and efficacious approaches to achieve lasting repair.

Keywords: Anterior skull base, Cranial trauma, Pericranial flap, Skull base fracture, Skull base repair

INTRODUCTION

While basal skull fractures are a common complication of severe head trauma, complex anterior skull base fractures – involving the frontal, ethmoid, or sphenoid bones – present special considerations due to the potential for orbital injury and as well as infection and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak secondary to the proximity of the air sinuses.[

CASE PRESENTATION

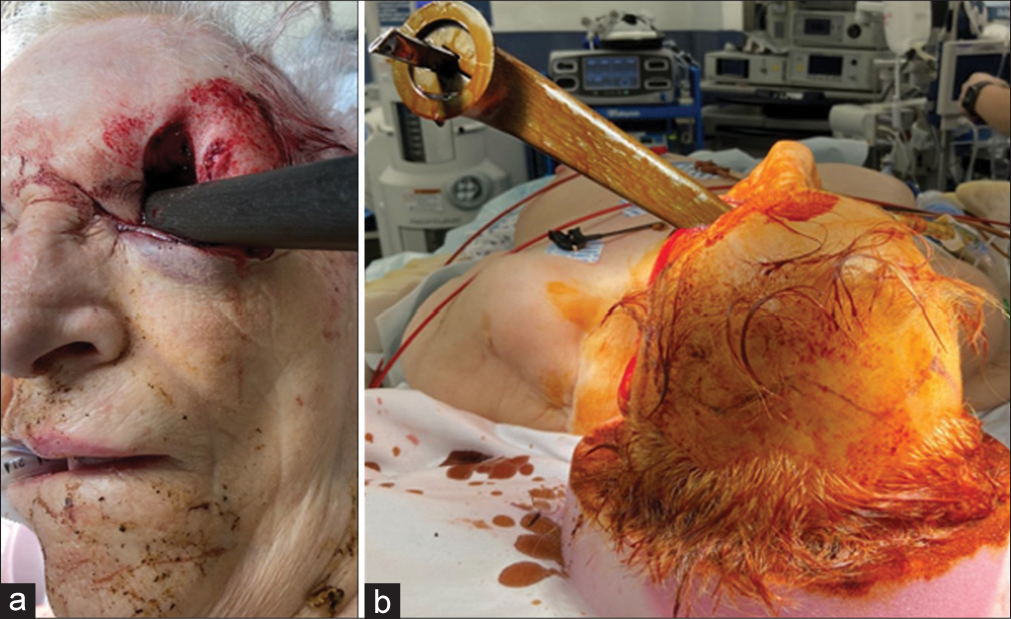

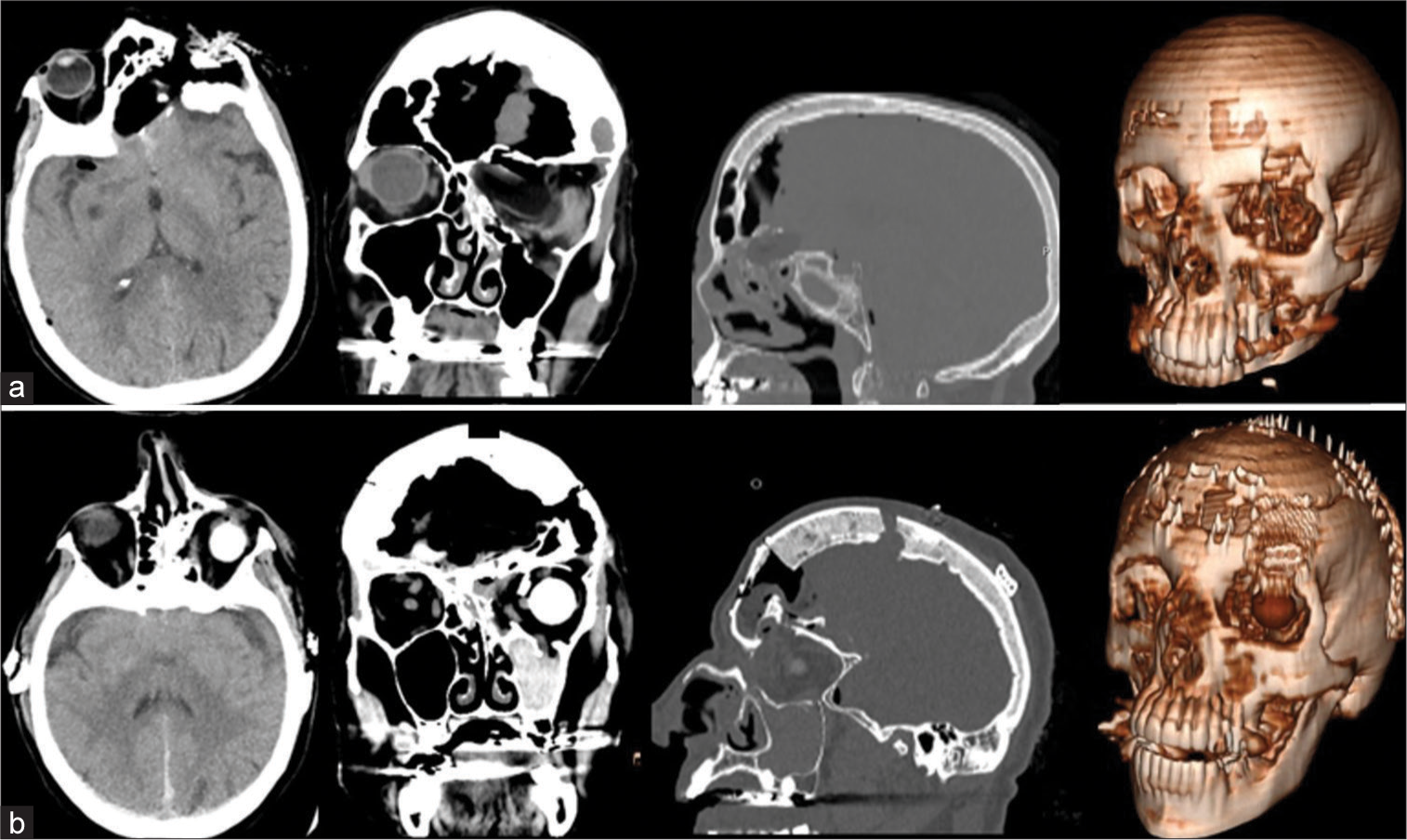

The patient is an 87-year-old female who presented after falling on a reclining chair lever, resulting in penetrating trauma to the left face [

Preoperatively, the patient was administered vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and levetiracetam for meningitis and seizure prophylaxis. Pain was controlled with IV fentanyl, and the patient remained within her systolic blood pressure goal of below 160. After induction of general anesthesia, the patient was placed supine and a bicoronal incision was made. The scalp was raised in a subgaleal plane and the temporoparietal fascia was used to raise a temporally-based pericranial flap. A bifrontal craniotomy was then performed and the foreign body was removed. After thorough irrigation, delicate hemostasis of the frontal lobe was achieved. Surgicel was placed over any areas of contusion or tissue disruption concerning for future bleeding. The left orbital rim was fractured, exposing the frontal sinus and mucosa underneath with a large anterior skull base defect noted at the orbital roof. The frontal sinuses were cranialized, and the mucosa was meticulously removed from the sinus wall. The pericranial flap was mobilized, rotated laterally, and laid over the large defect on the floor of the anterior skull base. Interrupted sutures were used to secure the flap to the dura. A split-thickness bone graft was harvested from the inner table of the frontal bone, placed on top of the defect, and secured with screws. Surgical and a gelatin-human thrombin matrix (Floseal) were used to aid in hemostasis; DuraGen was then applied for a multi-layered closure over the defect repair.

Given the extensive globe damage, the left eye evisceration was performed. Following this, autogenous abdominal fat previously harvested by the neurosurgical team was used to fill the space within the bilateral cranialized frontal sinuses. The craniotomy bone flap was then replaced.

Postoperatively, the patient was admitted to the neurological intensive care unit and continued on a 7-day course of vancomycin and ceftriaxone for meningitis prophylaxis. Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging and CT scans showed expected postsurgical changes. She was stable for discharge to a rehabilitation center after a hospital stay of 16 days. She was discharged from rehabilitation after 3 weeks. Over a 9-month follow-up period, there was no report of CSF leak or intracranial infection.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of an extensively complex anterior skull base fracture repair. The goal of skull base repair is to obtain a structurally secure, water-tight separation between intra and extracranial compartments to protect intracranial structures, prevent herniation, and minimize risk of infection or CSF leak.[

Lateral versus anterior pericranial flap

The pericranium is a scalp layer composed of the periosteum and overlying loose areolar connective tissue.[

Bone closure

The use of a split-thickness frontal bone graft was also demonstrated in this anterior skull base repair. In patients with complex defects, a cranial bone graft allows for structural repair to prevent brain herniation or migration of a pericranial flap, if used.[

Fat graft

For the present case, we opted to use an autogenous abdominal fat graft to fill the cranialized frontal sinuses to aid in closure of dead space. Grafted abdominal fat is easily available and has been shown to encourage healing and prevent regrowth of mucoperiosteum.[

CONCLUSION

When choosing the appropriate surgical approach to repair complex anterior skull base defects, paramount considerations include creating a watertight separation between intra and extracranial compartments to prevent infection and CSF leak, while maintaining protection of intracranial structures. Use of a pericranial flap, split-thickness cranial bone graft, and abdominal fat graft represent feasible and effective techniques to achieve these goals during defect repair.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Agrawal A, Garg LN. Split calvarial bone graft for the reconstruction of skull defects. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2011. 3: 13-6

2. Donald PJ. Frontal sinus ablation by cranialization: Report of 21 cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982. 108: 142-6

3. Eledeissi A, Ahmed M, Helmy E. Frontal sinus obliteration utilizing autogenous abdominal fat graft. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018. 6: 1462-7

4. Sakarunchai I, Tanikawa R, Ota N, Noda K, Matsukawa H, Kamiyama H. Toward a more rationalized use of a special technique for repair of frontal air sinus after cerebral aneurysm surgery: The most effective technique. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2016. 4: 6-10

5. Safavi-Abbasi S, Komune N, Archer JB, Sun H, Theodore N, James J. Surgical anatomy and utility of pedicled vascularized tissue flaps for multilayered repair of skull base defects. J Neurosurg. 2016. 125: 419-30