- Hacienda Publishing, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Miguel Faria, Hacienda Publishing, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_560_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Miguel Faria. “Plants of the Gods” and their hallucinogenic powers in neuropharmacology — A review of two books. 12-Jul-2021;12:343

How to cite this URL: Miguel Faria. “Plants of the Gods” and their hallucinogenic powers in neuropharmacology — A review of two books. 12-Jul-2021;12:343. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10965/

Abstract

“Plants of the Gods” is a term referring to the religious meaning members of many primitive cultures worldwide attribute to plants containing hallucinogenic or mind-altering substances. The plants are customarily considered sacred and consumed in religious rituals in an attempt to reach and communicate with gods or revered ancestors. They are frequently used in healing rites. Occasionally, they are used for purely recreational purposes, this being their main use in the modern societies of both industrialized and underdeveloped nations. However, it must be noted that the hallucinogenic or psychedelic experiences, recreational, are not always euphoric. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers is well-written, fully illustrated with color photographs, and contains a good index. It is an effective compilation of ethnographic, historic, and neuropharmacologic information on the hallucinogenic plants of planet Earth and the psychological and sociological impact they have, particularly in primitive societies. The behavioral side effects and toxic manifestations that may be associated with transient or permanent neurological deficits or psychiatric conditions place them in the realm of neuropsychiatry, when affected individuals present to the emergency room or are referred for medical consultation.

Keywords: Hallucinogenic plants, Mind-altering substances, Neuropharmacology, Neuropsychiatry, Psychoactive drugs

Title : The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge

Author : Carlos Castaneda (1925-1998)

Published by : University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA., USA

Hardcover : $39.95

Pages : 240

ISBN-13 : 978-0-520-29076-1

Year : 3rd edition, 2008

Title: Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers

Author : Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, Christian Rätsch

Published by : Healing Arts Press, Rochester, VT., USA

Softcover : $29.95

Pages : 208

ISBN-13 : 978-0-89281-979-9

Year : 2nd edition, 2001

PART I: A SORCERER’S APPRENTICE — THE TEACHINGS OF DON JUAN

I discovered the tome, Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers,[

According to Castaneda, Don Juan was a Yaqui Indian sorcerer from the Sonora desert area of Mexico, who accepted Castaneda as a student and took him under his tutelage for several years. The apprenticeship entailed the repeated and ritualistic use of hallucinogenic plants to assist Carlito in becoming “a man of knowledge,” a sorcerer and warrior, like his mentor Don Juan. The plants were categorized by Don Juan as “teachers” or “allies,” and would lead Carlito to reach a state of non-ordinary reality, a separate realm of reality.

By reaching a separate reality and becoming a sorcerer or warrior, Carlito would escape the mundane everyday existence that most of us lead and become inaccessible to old friends and family. As a man of knowledge in the state of non-ordinary reality, Carlito would attain vast amounts of supernatural powers by which he could then carry out extraordinary feats — such as fly great distances, converse with animals, render enemies harmless, vanquish powerful foes, and accept death without fear when it came.

Much of this information evolved over time in Castaneda’s subsequent books, but his first three books, written while he was still an anthropology student, became a sensation that catapulted the author to stardom. His first book, The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge (1969), was in fact his thesis for his PhD in anthropology. It was published by a university press and then republished by a commercial publisher with titanic commercial success. His other books quickly followed, but it was in the first book that he described the use and preparation of hallucinogenic plants utilized in his quest for knowledge.

After attaining fame and commercial success, Castaneda remained mysterious and inaccessible, a secretive man in all aspects of his life, while orchestrating from afar a vast following of admirers, students, and apprentices. Questions were asked and are still being asked about his anthropological apprenticeship, the veracity of his research, the existence of Don Juan, and the logical question of whether his PhD should have been given in anthropology or creative writing! Suffice to say that since the 1970s the literary reference to the persona of Don Juan shifted almost imperceptibly in America from the amorous Don Juan of Spanish literature to Don Juan Matus, the Yaqui sorcerer, “man of knowledge,” and mentor of Carlos Castaneda. (The reader should keep in mind that it is in fact Carlos Castaneda himself who is speaking through the persona of Don Juan and who is expounding his purported philosophy of life in all of his books.).

In reading the next book , Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers by ethnobotanists, Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann and Christian Rätsch, I found that the descriptions of the three main hallucinogenic plants Castaneda dealt with were largely accurate and the observations about the preparation and use of drugs perceptive. Moreover, because of their effects and toxicity, these plants and the psychoactive drugs they produce should be of interest to neuroscientists as well as neuropsychiatrists — from researchers in the laboratory to drug addiction and rehabilitation experts as well as neurologists and psychiatrists, especially professionals on call to emergency rooms since drug enthusiasts may present with acute seizures, delirium, delusions, or frank psychotic states.

Two plants in Don Juan’s armamentarium were considered “allies”: Psilocybe mexicana, a mushroom that was dried and smoked in a pipe and referred to as humito (“little smoke”) by Don Juan; and Jimsonweed or devil’s weed, a powerful psychoactive plant in the Nightshade family. The species utilized, Datura innoxia, was chewed and ingested or rubbed as an ointment to certain body parts. Both the smoked mushroom (humito) and the flowering plant Datura, also referred to as devil’s trumpet and Moonflower, helped the ritualistic consumer in his journey to attain a state of non-ordinary reality and wield supernatural powers.

A third hallucinogenic plant was the most powerful and, as a benevolent “teacher,” a deity in and of itself. Don Juan referred to this plant as mescalito. The plant not only assisted the user in reaching a separate reality but also taught great lessons that would lead to a better ordinary life. The source was peyote, Lophophora williamsii, a cactus species grown in Mexico and the American southwest. The top part of the cactus was cut off, collected, and dried. Later these peyote “buttons” were ritualistically chewed and ingested, a couple of pieces at a time. Don Juan and Carlito participated in several such ceremonies described in the early books.[

But before I go into detail about the ethnobotany and neuropharmacology discussed in Plants of the Gods and the implications for neuropsychiatry,[

Before the advent of Carlos Castaneda in the 1960s, “Don Juan” was indelibly associated with the amorous, fictitious and devilish libertine brought to life by the 17th century Spanish dramatist, Tirso de Molina. Don Juan has continued to occupy a central place in Spanish literature, been immortalized in the play Don Juan Tenorio by Jose Zorrilla, and celebrated in all of Western literature in the poetry of Lord Byron. But for many American baby boomers of the 1960s, “Don Juan” conjures up images of Castaneda’s Don Juan Matus, the Yaqui sorcerer from the Sonora desert.

And let me just give you another example. Castaneda’s books were so popular in their day that American director, film producer, and screenwriter Oliver Stone named his movie production company, Ixtlan Productions (2007), after Castaneda’s third book, Journey to Ixtlan. So why not mix a little literature with ethnobotany and neuropharmacology?

During my college days, I did not have time to read Carlos Castaneda’s books and learn about Don Juan’s Yaqui way of knowledge. Frankly, I was too busy with pre-med courses to read those books, although the temptation was there. Castaneda’s books with their appropriately colorful covers were arranged, front and center, in stacks at my college bookstore in the Russell House, the epicenter of student culture on the University of South Carolina campus in Columbia, South Carolina.

Now 50 years later, following the Aristotelian philosophy of the good life by spending time in my garden as well as reading the classics, I finally found time to read Castaneda’s entertaining series and check the veracity concerning hallucinogenic drugs and neurochemistry.

PART II: “PLANTS OF THE GODS”

“Plants of the Gods” is a term referring to the religious meaning members of many primitive cultures worldwide attribute to plants containing hallucinogenic or mind-altering substances. The plants are customarily considered sacred and consumed in religious rituals in an attempt to reach and communicate with gods or revered ancestors. They are frequently used in healing rites. Occasionally, they are used for purely recreational purposes, this being their main use in the modern societies of both industrialized and underdeveloped nations. However, it must be noted that the hallucinogenic or psychedelic experiences, recreational, are not always euphoric.

Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers is well-written, fully illustrated with color photographs, and contains a good index. It is an effective compilation of ethnographic, historic, and neuropharmacologic information on the hallucinogenic plants of planet earth and the psychological and sociological impact they have, particularly in primitive societies. The book could have been better organized in terms of grouping plants by their pharmacologic effects rather than cataloguing them in alphabetical order. Additional ethnographic chapters do significantly enhance the narrative and compensate for the cataloguing sections. All things considered, the authors have done a splendid job researching the plants and bringing forth associated ethnographic information.

Most of the hallucinogenic substances contained in these plants are toxic, but for the most part follow the principle of hormesis[

The behavioral side effects and toxic manifestations that may be associated with transient or permanent neurological deficits or psychiatric conditions place them in the realm of neuropsychiatry, when affected individuals present to the emergency room or are referred for medical consultation.

I have tried to classify the plants according to their pharmacologic mode of action. But an encyclopedic book of this magnitude with hundreds of plants is a difficult task so I have selected a few of the major groups containing the most interesting plants with similar neuropharmacology to give this book fair exposure.

THE NIGHTSHADE PLANTS AND THE TROPANE ALKALOIDS

The Nightshade flowering plants (Solanaceae family) have been known in Europe since the Middle Ages because of their long history of use in witchcraft and divination. The major plants in this family include Mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), Henbane, Belladonna (Atropa belladonna; deadly nightshade), and several Datura species, such as Thorn Apple (Datura stramonium) and D. innoxia, “Devil’s Trumpet,” which we have already mentioned as devil’s weed and Jimsonweed. I have also heard it referred to as Moonflower [

Belladonna, mandrake, and henbane come from Mediterranean Europe and North Africa. During the middle ages, all three plants were used or were implicated for their use in witches brew and imbued with magic powers and used in potions or ointments in both witchcraft and healing rituals. In the 11th century the defending Scots annihilated an invading Norwegian army by sending them food and beer laced with “Sleepy Nightshade” (Belladonna). The Mandrake root that resembles a human figure was particularly feared (a good example of imitative magic) for its hypnotic and hallucinogenic properties, as well as for its lethality as a poison in higher doses [

Previously, we mentioned D. innoxia in the context of the teachings of Don Juan. Datura plants grow in the tropical and subtropical regions of both hemispheres. In Mexico, the plants, referred to as Toloache, are considered one of the main plants of the gods and used extensively for their psychoactive effects. It was consumed by both the Mayans and the Aztecs in ancient times. The eminent Maya scholar Eric Thompson wrote in The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization[

The present-day Tarahumara Indians of Mexico mix Datura plants (Toloache) with maize to make a ceremonial drink. Furthermore, they believe that Toloache is possessed by a malevolent spirit, just as Don Juan, the Yaqui teacher, also believed.

The active principles in the Nightshade plants are the chemicals atropine, scopolamine (a potent hallucinogenic tropane alkaloid), hyoscyamine, and other tropane alkaloids. These alkaloids are present in fresh plants and their dried roots, and have toxic effects because of their anticholinergic (i.e., nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, and paralysis) and strong psychoactive effects (i.e., hallucinations, delusions, psychosis, and seizures).

THE CACTUS PEYOTE AND THE CATECHOLAMINE DERIVATIVES

Cacti (Cactaceae; cactus family) were so named by Theophrastus (371-287 BC), naturalist and philosopher successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic School, after a spiny plant now lost. The main cactus in this category we have already mentioned — peyote (L. williamsii) — a cactus that grows in Mexico and Texas in the driest of desert regions [

There are also false peyote species that are widely used by the Tarahumara Indians because these cacti are also hallucinogenic. The active principle in peyote is mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenylethylamine) a psychoactive phenylethylamine, related to the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (as well as to the catecholamines dopamine, a neurotransmitter, and epinephrine, a hormone). Therefore, mescaline acts as a sympathomimetic drug that mimics the effects of the catecholamines, the endogenous agonists of the sympathetic nervous system mentioned above, which can act as central nervous system (CNS) neurotransmitters or systemic hormones.

THE MUSHROOM PSILOCYBE AND THE INDOLE ALKALOID DERIVATIVES

The mushrooms (Strophariaceae family) of the genus Psilocybe are a third group of hallucinogenic plants. There are many Psilocybe species, and they are found nearly worldwide, but ethnographically are centered in Mexico, where they are nearly venerated by various indigenous groups [

The Aztecs called these mushrooms Teonanácatl (“divine flesh”), and as we have mentioned, the Mayans also ingested them, although peyote may have been the most commonly used hallucinogen in both civilizations, as well as by most other Mesoamerican cultures.

Psilocybe cyanescens, the wavy cap mushroom species, have a wavy brown cap but unlike P. mexicana, grows in decaying plants, “coniferous mulch, and humus-rich soil.” Reportedly, it has been used in neo-pagan rites in Central Europe and North America. “Visionary doses are 1 g of the dried mushroom, which contains approximately 1% tryptamine (e.g., psilocybin(e) and psilocin(e).”[

The active principles in these mushrooms — that is, psilocybin and psilocin — are indole alkaloids, related to tryptamine and the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxy tryptamine), of which the amino acid tryptophan is a precursor. Serotonin is the neurotransmitter that regulates mood, and psilocybin and its derivative psilocin are psychoactive compounds that are lipid soluble — that is, lipophilic and thus capable of easily crossing the blood–brain barrier. Therefore they are potent hallucinogens. The tryptamine compounds are very structurally (and functionally) similar to serotonin. They bind at the 5-HT receptors, acting as serotonin agonists and mimicking the psychoactive properties of serotonin in the CNS. The primary action is mood enhancing, as to cause happiness and euphoria.[

Lysergic acid derivatives are also indole alkaloids related to serotonin, and the powerful semi-synthetic hallucinogen LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) also binds 5-HT and even some dopamine receptors acting as serotonin and dopamine agonists, mimicking and amplifying the psychoactive properties of these neurotransmitters in the CNS, inducing the well-described psychedelic effects reported by users. The exact mechanism of how it happens is unknown.[

In Mexico, several varieties of morning glories (Turbina corymbosa) referred to as Ololiuqui and bindweed vines (Ipomoea violacea) are considered sacred plants because of their hallucinogenic powers. Both the Zapotec and Aztec Indians consumed the seed of these plants containing lysergic acid compounds that also act through the serotonin psychoactive pathways, as with psilocybin and psilocin. They continue to be used for religious and curing rituals by modern Indians throughout Mexico, including the Mazatecs and the Zapotecs in the Oaxaca region.

In the Orinoco river basin between Colombia and Venezuela, the Guahibo Indians use a powerful tobacco snuff, Cohoba, which is hallucinogenic, and to which the local Indians refer to as Yopo. It had been recorded by Spanish explorers as early as 1496 that Cohoba may have been brought by the Taino Indians of the Caribbean and used as a snuff mixed with tobacco to communicate with the spirit world from earlier times. Cohoba comes from the beans of the Yopo tree, Anadenanthera peregrina, that was part of the flora studied by the German naturalist Baron Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) in the early 1800s.

The Guahibo Indians take Yopo snuff (Cohoba) in the course of the day as a stimulant, “while their shamans use it to induce trances to communicate with the Hekula spirits to prophesize or divine; to protect the tribe against epidemics of sickness; to make hunters and even their dogs more alert.”[

The active principle in the chemistry of the Yopo tree (Anadenanthera) derivatives is the open and close rings of the tryptamine (indole alkaloids) neurochemicals related to serotonin.

Incidentally, plants are not the only source of psychoactive substances. Toads, frogs, and certain fish have been described as containing tryptamine compounds in their secretions. For example, bufotenine, an open tryptamine found in the Anadenanthera tree, is secreted in the skin of a Bufo species of toad.[

THE FUNGUS CLAVICEPS PURPUREA AND ERGOT POISONING

The ergot fungus, C. purpurea, is found in temperate areas of Europe, Asia, and North America. Ergot is a parasitic disease of grasses and sedges, principally rye. (Claviceps stands for the fungus sclerotium, or spur, attached to the infected grain) [

In ergot poisoning the active principles are again indole alkaloids derivatives — that is, ergotamine and ergotoxine — that cause severe vasoconstriction responsible for ergotism and gangrene. Other psychotropic lysergic acid amides are responsible for the convulsions, delirium, and madness. Amazingly, these psychotropic derivatives are similar to those found in Mexican morning glories and bind weeds previously mentioned.[

Recent investigations suggest that psychotropic ergot derivatives may have played a role in the Eleusinian mysteries of ancient Greece. It has been found that ergotamine and ergotoxine, the chemicals responsible for the worse toxic effects of ergotism, are insoluble. Therefore, an initiate would drink a measured volume of the sacred mixture of water with ergot-contaminated barley and other wild grasses, and because the milder psychoactive alkaloids (i.e., lysergic acid derivatives) are water-soluble, he would have visions while drinking the infusion, but not get ergotism. The hallucinogenic mechanism is suspected to be similar to what we have described with the indole alkaloid derivatives, serotonin, and lysergic acid derivatives.

CANNABIS SATIVA, OPIUM, AND COCAINE

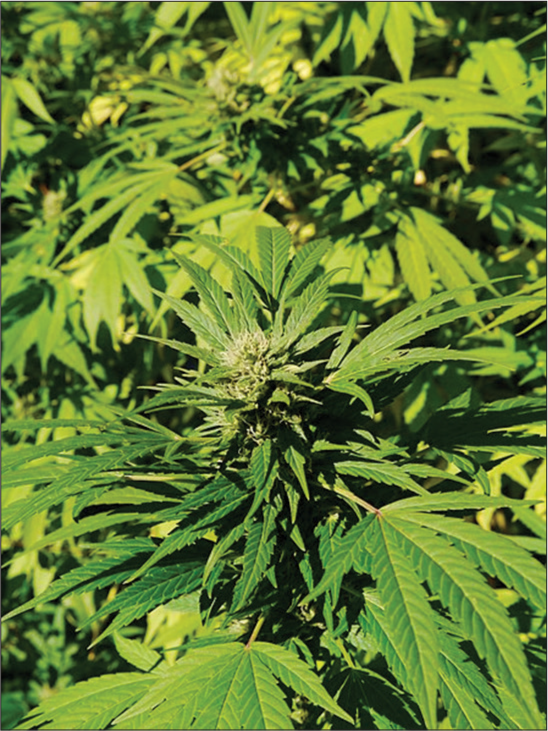

In the Hemp family, C. sativa, is a plant that is grown worldwide and is known as hashish, hemp, weed, marijuana, and by a myriad other names [

Nevertheless, marijuana can have adverse side effects that are well known to physicians — from gynecomastia to chronic respiratory infections. In chronic users, it can also predispose to anxiety and depression or aggravate chronic psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia. This should not be surprising as chronic psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia, involve several neural pathways that involve microglia activation and inflammation[

Hemp (marijuana) was mentioned by the Greek geographer and historian Strabo (c. 63 BC-AD 21) in his Geography as growing in Colchis in Scythia, and he referred to “Getae dancers who burned cannabis flowers to reach states of ecstasy.”[

The exact mechanism of how THC acts to alter mood and cognition and other psychogenic effects is not known, but it is known that the drug induces its most powerful effects by binding to its own cannabinoid receptors in the brain and that additional psychotropic effects may take place by the indirect release of dopamine.[

Another group of plants that should be mentioned for the sake of completeness are the opioids closely related to the narcotics. If the book, Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers, is deficient in one area, it is in the brief description of narcotics and cocaine. This could be related to the fact that narcotics produce euphoria but are generally not hallucinogenic. In fact, morphine, a well-known narcotic drug produced from the opium poppy plant, is named after the Greek god of sleep, Morpheus, because of its hypnotic qualities — in the same fashion as the scientific name of the opium poppy plant itself, Papaver somniferum.

We should also mention the drug cocaine, extracted from the leaves of two coca species of plants (Erythroxylaceae coca), it is also a tropane alkaloid. Coca plants grow in western South America, and it is a cash crop for several countries in the region — for example, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and parts of Argentina. It is an indirect sympathomimetic drug that crosses the blood–brain barrier and blocks the transport of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, inhibiting the re-uptake of these neurotransmitters at the presynaptic terminals, thus increasing their quantity, as well as the activation of the receptors in the postsynaptic neurons. This intense agonist activation results in the well-known effects of cocaine intoxication — euphoria, tachycardia, sexual arousal, agitation, and loss of contact with reality, which can result in frank psychotic states.[

Cocaine has been used by South American Indians for hundreds of years, from the time of the Incas to their present-day descendants in the Andean region. Chewing the leaves helps them combat hunger, fight inclement weather, ease fatigue, and alleviate altitude sickness.

CONCLUSION

I recommend Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Power with the following caveat: The book was published 20 years ago, and during that time many advances have been made in the area of neuropharmacology.[

I also recommend The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. In fact, Carlos Castaneda’s first four books make delightful, recreational reading by offering a form of escapism. But make no mistake, Castaneda’s books should be read as works of fiction, except for the accurate description of the hallucinogenic drugs and their effects contained in his first book, The Teachings of Don Juan. Otherwise, read them for pure enjoyment and entertainment.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Azizi SA. Monoamines: Dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, beyond modulation “switches” that alter the state of target networks-a review article. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 04].

2. Blaylock RL. Inflammation. Available from: https://www.haciendapublishing.com/inflammation-immunoexcitotoxicity-and-microglia-activation-in-schizophrenia-by-russell-l-blaylock-m-d [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 04].

3. Carod-Artal FJ. Psychoactive plants in ancient Greece. Neurosci Hist. 2013. 1: 28-38

4. Castaneda C.editors. The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. Berkeley, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2008. p.

5. Faria MA. Frontal lobe syndromes in neuropsychiatry-a book review. Surg Neurol Int. 2020. 11: 439

6. Faria MA. Glyphosate, neurological diseases-and the scientific method. Surg Neurol Int. 2015. 6: 132

7. Faria MA. The Neuropsychiatry of the Limbic System-A Book Review. Available from: https://www.haciendapublishing.com/a-book-review-of-the-neuropsychiatry-of-limbic-andsubcortical-disorders [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 04].

8. McKenna J, Arzt N.editors. The Long-Term Side Effects of Marijuana Use. United States: WebMD; 2020. p.

9. Nichols DE. Hallucinogens. Pharmacol Ther. 2004. 101: 131-81

10. Schele L, Miller ME.editors. Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York: George Braziller; 1986. p.

11. Schultes RE, Hofmann A, Rätsch C.editors. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 2001. p.

12. Thompson JE.editors. The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1954. p. 250

13. Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endocannabinoid signaling in the brain. Science. 2002. 296: 678-82

Timothy W. Wheeler, MD

Posted July 19, 2021, 2:02 pm

Dr. Faria, your article brings back many memories of my undergrad and med school days. The Harvard group—Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (aka “Baba Ram Dass”) and peripherally, Andrew Weil—all experimented with various psychedelic drugs before the former two were fired from Harvard and Weil went on to become an alternative medicine guru in Tucson. Aside from their controversial experimentation with these powerful drugs, Weil was in his early career a serious student of ethnopharmacology. He was a guest lecturer at my medical school. As a chemistry major, I was intrigued by the similarity of these compounds to human hormones. Thank you for this historical review.

Dr. Miguel A. Faria

Posted July 19, 2021, 2:53 pm

Hello Dr Wheeler, Thank you for the vignette and your memories that serve as marvelous, additional illustrations for my article.