- Department of Neurological Surgery, Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, United States.

- Department of Neurological Surgery, School of Medicine, Wayne State University, United States.

- Department of Neurological Surgery, Sinai Grace Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States.

- Seattle Science Foundation, Swedish Neuroscience Institute, Seattle, Washington, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Swedish Neuroscience Institute, Seattle, Washington, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Ankush Chandra

Department of Neurological Surgery, Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, United States.

Department of Neurological Surgery, Sinai Grace Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_245_2019

Copyright: © 2019 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Ankush Chandra, Seong-Jin Moon, Blake Walker, Emre Yilmaz, Marc Moisi, Robert Johnson. Postoperative intracranial migration of a C2 odontoid screw: A case report and literature review. 10-Sep-2019;10:173

How to cite this URL: Ankush Chandra, Seong-Jin Moon, Blake Walker, Emre Yilmaz, Marc Moisi, Robert Johnson. Postoperative intracranial migration of a C2 odontoid screw: A case report and literature review. 10-Sep-2019;10:173. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9619/

Abstract

Background: Intracranial migration of odontoid screws is a rare but serious complication of anterior odontoid screw fixation not often reported in literature by neurosurgeons. Here, we describe the second case in literature of intracranial migration of an odontoid screw.

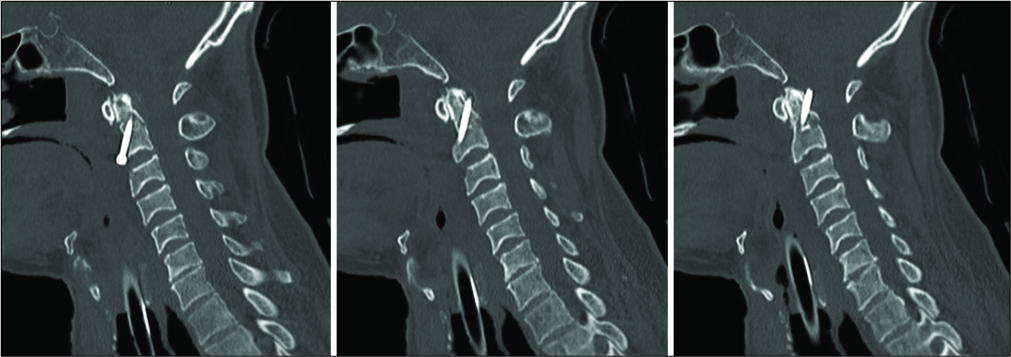

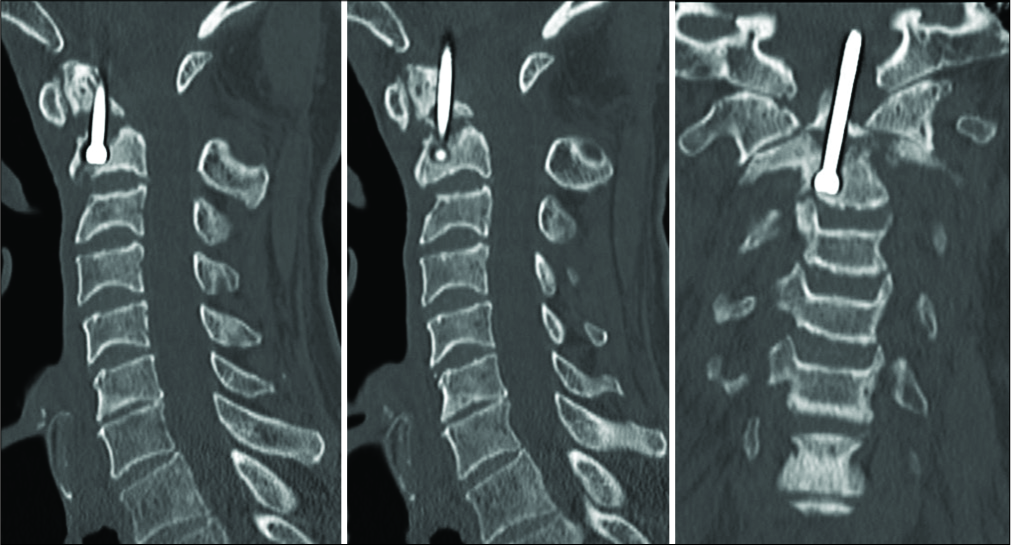

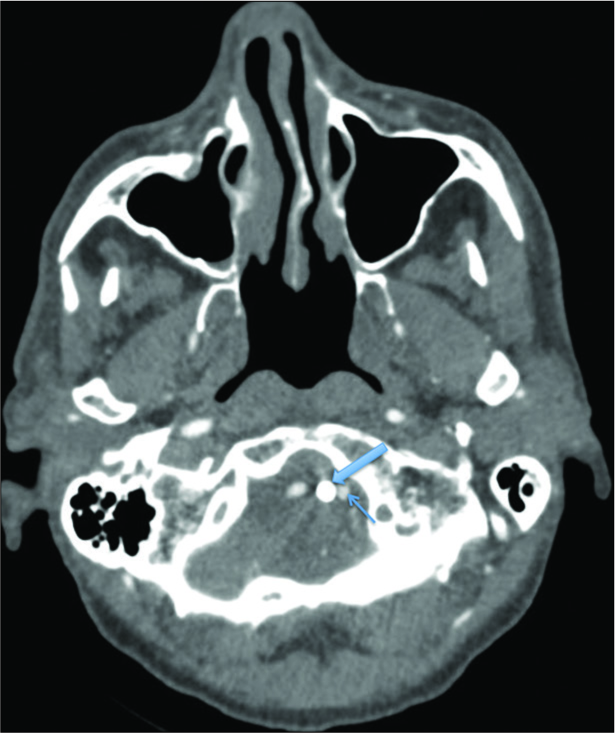

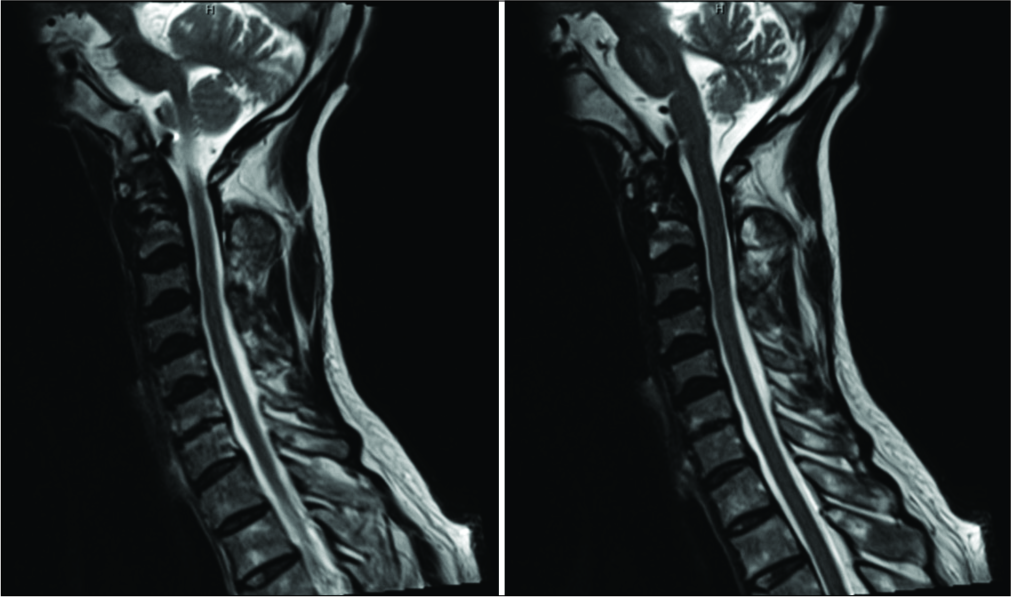

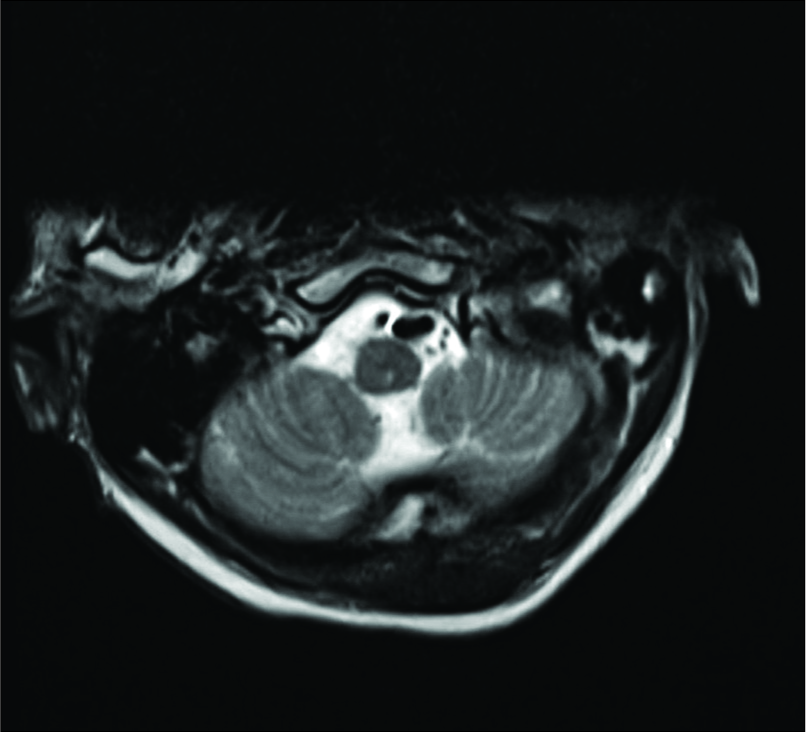

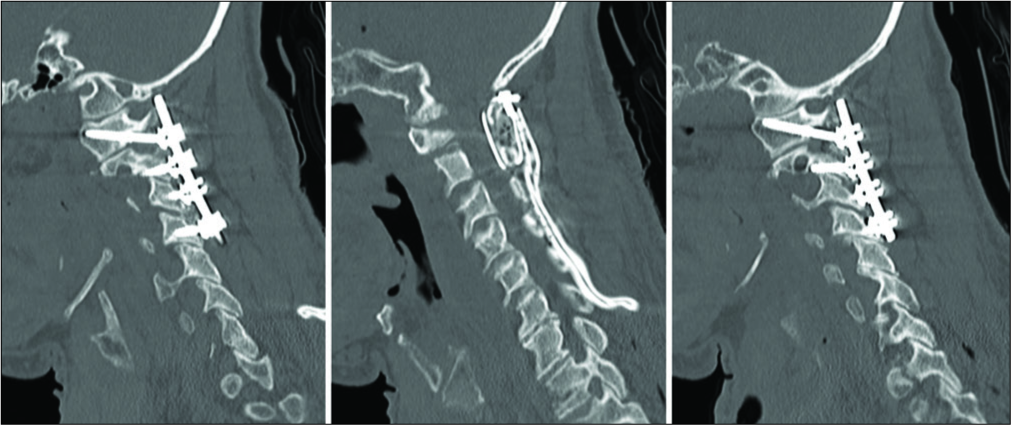

Case Description: A 64-year-old neurologically intact patient with a type II odontoid fracture secondary to trauma underwent anterior odontoid screw fixation without any intraoperative complications. He tolerated the procedure well, and postoperative imaging demonstrated near anatomic correction of the fracture with satisfactory placement of the lag screw. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow up and he presented 7 months later for a routine outpatient computed tomography (CT) of the cervical spine, which demonstrated upward migration of the screw into the intracranial cavity abutting the medulla, with CT angiography of the neck also confirming the screw lying between the two vertebral arteries. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine also demonstrated the odontoid screw lying within close proximity to the ventral cervicomedullary junction, marginating the left vertebral artery. Subsequently, the patient was managed with removal of the odontoid screw and posterior cervical arthrodesis and instrumented fusion.

Conclusion: Our case demonstrates the rare but serious complication of intracranial odontoid screw migration, which we bring to the attention of the neurosurgical community. The recognition of risk factors for this complication and optimized management of this rare occurrence is important for surgeons to recognize.

Keywords: Anterior odontoid screw fixation, C2 odontoid screw, Postoperative intracranial migration

INTRODUCTION

Odontoid fractures are the most common cervical spine fractures with an occurrence of approximately 20% of all cervical fractures.[

Treatment options for type II odontoid fractures can be conservative or surgical. Due to the patient discomfort and high risk of nonunion and mortality with conservative approaches in a subpopulation of patients, surgical stabilization is typically favored and is becoming the norm for this subpopulation.[

We present a rare case of a 64-year-old male who presented with a posttraumatic type II odontoid fracture which was managed through AOSF. A routine computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine 7 months later demonstrated intracranial migration of the screw, with the patient undergoing subsequent removal of the screw and PCIF. To the best of our knowledge, intracranial migration of odontoid screws has only been described in literature once, making our case, the second reported case of upward migration of an odontoid screw. We provide a comprehensive review of literature demonstrating postoperative migration of anterior odontoid screws and discuss the current management that spine surgeons must face when dealing with this rare, yet critical, complication.

CASE DESCRIPTION

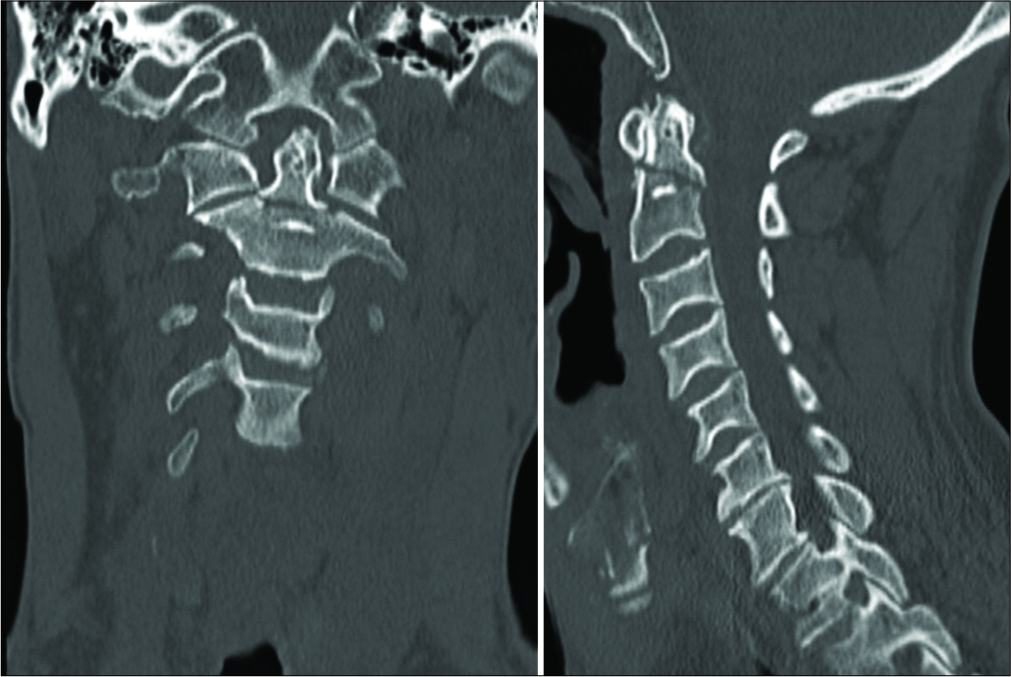

A 64-year-old male presented as an intoxicated pedestrian who was involved in a hit-and-run incident. Initial trauma workup demonstrated that the patient had sustained a type II odontoid fracture [

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the C2 odontoid process are the most common cervical injury.[

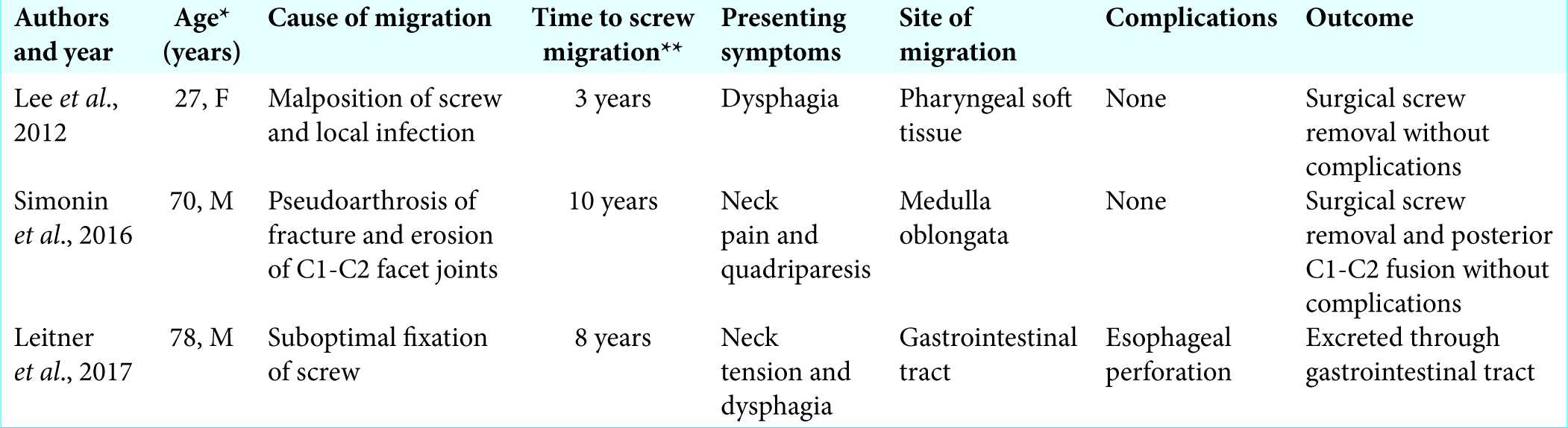

Screw loosening and migration are well-recognized complications of several spine procedures. There are some rare occurrences reported in literature.[

There has been some consideration in literature evaluating two-screw fixation versus single screw fixation. Jenkins et al. demonstrated that in a series of 42 consecutive patients with odontoid screw placement, there was no significant difference in the successful union rates between one and two-screw fixation techniques (fusion was found to be 81% and 85%, respectively).[

Postoperative anterior or posterior migration of odontoid screws is rarely reported in literature, being reported in literature only three times [

To rectify the fixation and nonfusion of the fracture, we performed a PCIF and C1-C4 posterolateral arthrodesis and instrumented fusion following anterior screw removal. While PCIF is typically done to fuse C1-C2, we extended the fusion from C1-C4 to provide additional robustness to the fusion given that our patient was elderly and that his fracture still showed significant nonfusion in spite of 7-month post-AOSF.

CONCLUSION

Intracranial migration of odontoid screws is a rare but serious complication of AOSF. Here, we report the second case in literature of intracranial migration of an odontoid screw in a neurologically intact patient, managed with subsequent removal and PCIF. Our case demonstrates the rare but serious complication of intracranial odontoid screw migration, which we bring to the attention of the neurosurgical community.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Ankush Chandra is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Med Research Fellow.

References

1. Anderson LD, D’Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974. 56: 1663-74

2. Andersson S, Rodrigues M, Olerud C. Odontoid fractures: High complication rate associated with anterior screw fixation in the elderly. Eur Spine J. 2000. 9: 56-9

3. Cagli S, Isik HS, Zileli M. Cervical screw missing secondary to delayed esophageal fistula: Case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2009. 19: 437-40

4. Clark CR, White AA. Fractures of the dens. A multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985. 67: 1340-8

5. Dunn ME, Seljeskog EL. Experience in the management of odontoid process injuries: An analysis of 128 cases. Neurosurgery. 1986. 18: 306-10

6. Geisler FH, Cheng C, Poka A, Brumback RJ. Anterior screw fixation of posteriorly displaced type II odontoid fractures. Neurosurgery. 1989. 25: 30-7

7. Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Odontoid fractures: Update on management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010. 18: 383-94

8. Joaquim AF, Patel AA. Surgical treatment of Type II odontoid fractures: Anterior odontoid screw fixation or posterior cervical instrumented fusion. ? Neurosurg Focus. 2015. 38: E11-

9. Kim SJ, Ju CI, Kim DM, Kim SW. Delayed esophageal perforation after cervical spine plating. Korean J Spine. 2013. 10: 174-6

10. Lee EJ, Jang JW, Choi SH, Rhim SC. Delayed pharyngeal extrusion of an anterior odontoid screw. Korean J Spine. 2012. 9: 289-92

11. Lee PC, Chun SY, Leong JC. Experience of posterior surgery in atlanto-axial instability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984. 9: 231-9

12. Leitner L, Brückmann CI, Gilg MM, Bratschitsch G, Sadoghi P, Leithner A. Passage of an anterior odontoid screw through gastrointestinal tract. Case Rep Med. 2017. 2017: 2923696-

13. Mazur MD, Mumert ML, Bisson EF, Schmidt MH. Avoiding pitfalls in anterior screw fixation for Type II odontoid fractures. Neurosurg Focus. 2011. 31: E7-

14. Nourbakhsh A, Garges KJ. Esophageal perforation with a locking screw: A case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007. 32: E428-35

15. Pompili A, Canitano S, Caroli F, Caterino M, Crecco M, Raus L. Asymptomatic esophageal perforation caused by late screw migration after anterior cervical plating: Report of a case and review of relevant literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002. 27: E499-502

16. Scheyerer MJ, Zimmermann SM, Simmen HP, Wanner GA, Werner CM. Treatment modality in Type II odontoid fractures defines the outcome in elderly patients. BMC Surg. 2013. 13: 54-

17. Simonin A, Borsotti F, Chittur-Viswanathan G, Duff JM. Progressive quadriparesis caused by anterior odontoid screw upward migration in rheumatoid arthritis. Spine J. 2016. 16: e309-10

18. Subach BR, Morone MA, Haid RW, McLaughlin MR, Rodts GR, Comey CH. Management of acute odontoid fractures with single-screw anterior fixation. Neurosurgery. 1999. 45: 812-9

19. Wu AM, Jin HM, Lin ZK, Chi YL, Wang XY. Percutaneous anterior C1/2 transarticular screw fixation: Salvage of failed percutaneous odontoid screw fixation for odontoid fracture. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017. 12: 141-

20. Yee GK, Terry AF. Esophageal penetration by an anterior cervical fixation device. A case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993. 18: 522-7