- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

Correspondence Address:

Joseph Maroon

Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_45_18

Copyright: © 2018 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Joseph Maroon, Jeff Bost. Review of the neurological benefits of phytocannabinoids. 26-Apr-2018;9:91

How to cite this URL: Joseph Maroon, Jeff Bost. Review of the neurological benefits of phytocannabinoids. 26-Apr-2018;9:91. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/review-of-the-neurological-benefits-of-phytocannabinoids/

Abstract

Background:Numerous physical, psychological, and emotional benefits have been attributed to marijuana since its first reported use in 2,600 BC in a Chinese pharmacopoeia. The phytocannabinoids, cannabidiol (CBD), and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) are the most studied extracts from cannabis sativa subspecies hemp and marijuana. CBD and Δ9-THC interact uniquely with the endocannabinoid system (ECS). Through direct and indirect actions, intrinsic endocannabinoids and plant-based phytocannabinoids modulate and influence a variety of physiological systems influenced by the ECS.

Methods:In 1980, Cunha et al. reported anticonvulsant benefits in 7/8 subjects with medically uncontrolled epilepsy using marijuana extracts in a phase I clinical trial. Since then neurological applications have been the major focus of renewed research using medical marijuana and phytocannabinoid extracts.

Results:Recent neurological uses include adjunctive treatment for malignant brain tumors, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, neuropathic pain, and the childhood seizure disorders Lennox-Gastaut and Dravet syndromes. In addition, psychiatric and mood disorders, such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, addiction, postconcussion syndrome, and posttraumatic stress disorders are being studied using phytocannabinoids.

Conclusions:In this review we will provide animal and human research data on the current clinical neurological uses for CBD individually and in combination with Δ9-THC. We will emphasize the neuroprotective, antiinflammatory, and immunomodulatory benefits of phytocannabinoids and their applications in various clinical syndromes.

Keywords: Cannabidiol, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, endocannabinoid system, neurological disease, phytocannabinoids

INTRODUCTION

Numerous physical, psychological, and emotional benefits have been attributed to marijuana since it was first reported in 2,600 BC (e.g., Chinese pharmacopoeia). The phytocannabinoids, cannabidiol (CBD), and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the most studied extracts from the cannabis sativa subspecies, include hemp and marijuana. Recently, it has been successfully utilized as an adjunctive treatment for malignant brain tumors, Parkinson's disease (PD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), multiple sclerosis (MS), neuropathic pain, and the childhood seizure disorders, Lennox-Gastaut and Dravet syndromes. In this review, we provide animal/human research data on the current clinical/neurological uses for CBD alone or with Δ9-THC, emphasizing its neuroprotective, antiinflammatory, and immunomodulatory benefits when applied to various clinical situations.

Discovery of the endocannabinoid system

Cannabinoid receptor pharmacology began in the late 1960s when Δ9-THC was isolated and synthesized and found to be the primary psychoactive constituent of marijuana.[

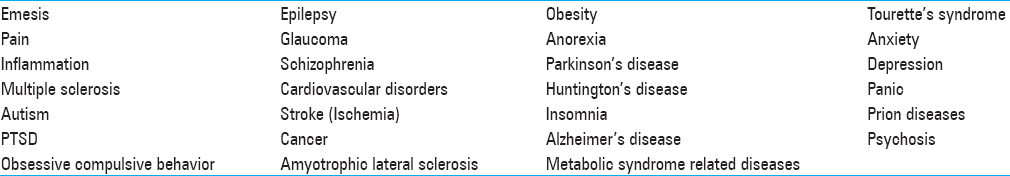

Table 1

Conditions and Diseases in Which Activation of The ECS has Shown Benefit[

Phytocannabinoids CBD and Δ9-THC

In addition to the phytocannabinoid Δ9-THC, it is estimated that the cannabis plant consists of over 400 chemical entities, of which more than 60 of them are phytocannabinoid compounds. Some of these compounds have been identified as acting uniquely on both CB1 and CB2 receptors separately and simultaneously, and/or to inhibit or activate receptor functions. CBD, like Δ9-THC, is a major phytocannabinoid accounting for up to 40% of the plant's extract. CBD was first discovered in 1940 more than 20 years before Δ9-THC.[

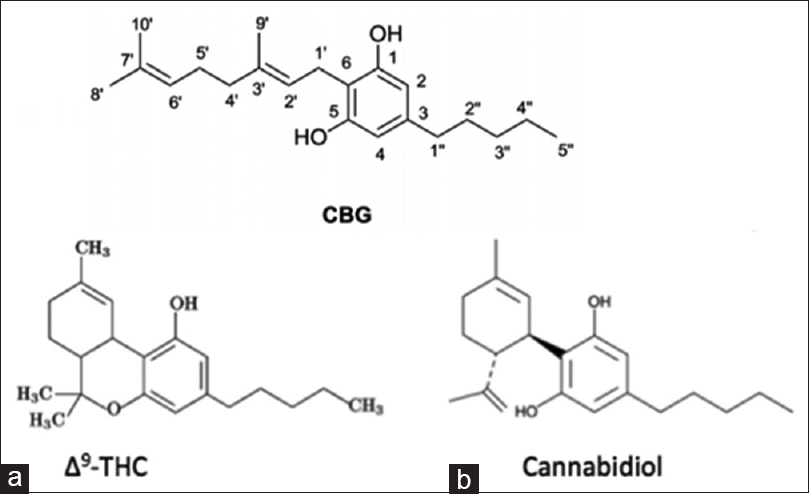

Figure 1

(a) Δ9-THC and (b) cannabidiol (CBD) are biosynthesized as tetrahydrocannabonolic acid (THC-A) and cannabidolic acid (CBD-A) from a common precursor cannabigerolic acid (CBG). These phytocannabinoids in their natural acidic form are considered “inactive”. When cannabis grows, it produces THC-A and CBD-A, not Δ9-THC and CBD. When cannabis is heated, such as through smoking, cooking, or vaporization, THC-A and CBD-A are decarboxylated into Δ9-THC and CBD (i.e. “active” forms)[

Cannabinoid receptors

Phytocannabinoid compounds and extracts can come from both hemp and marijuana subspecies, including CBD. CBD does not elicit the same psychoactive effects as seen with Δ9-THC (i.e., users of CBD do not feel euphoric). The various psychoactive effects generally associated with Δ9-THC are attributed to activation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor found abundantly in the brain. CB1 receptors have the highest densities on the outflow nuclei of the basal ganglia, substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), and the internal and external segments of the globus pallidus (a portion of the brain that regulates voluntary movement).[

Activation of neuronal CB1 receptors

Activation of neuronal CB1 receptors results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and decreased neurotransmitter release through blockade of voltage-operated calcium channels.[

The CB2 receptor

The CB2 receptor, unlike CB1, is not highly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS). Effects of Δ9-THC on immune function have been attributed to the CB2 cannabinoid receptor interaction found predominantly in immune cells.[

Cultured microglial dells

A study of cultured microglial cells showed c-interferon and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), known as inflammatory response activators of microglial cell, were accompanied by significant CB2 receptor upregulation.[

Unique mechanisms of CBD

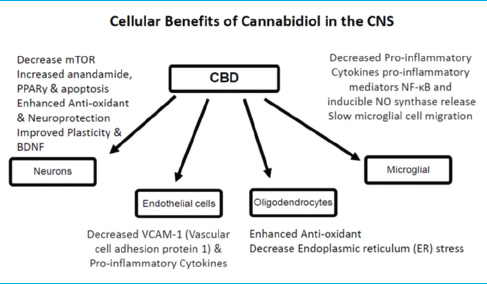

The interaction of CBD with CB2 receptors is more complex, but like Δ9-THC, CBD is believed to reduce the inflammatory response. CBD's action with the CB2 receptor is just one of several pathways by which CBD can affect neuroinflammation [

Molecular targets of CBD

Molecular targets of CBD, including cannabinoid and noncannabinoid receptors, enzymes, transporters, and cellular uptake proteins, help to explain CBD's low-binding affinity to both CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors. In animal models, CBD has demonstrated an ability to attenuate brain damage associated with neurodegenerative and/or ischemic conditions outside the ECS. CBD appears to stimulate synaptic plasticity and facilitates neurogenesis that may explain its positive effects on attenuating psychotic, anxiety, and depressive behaviors. The mechanisms underlying these effects involve multiple cellular targets to elevate brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) levels, reduce microglia activation, and decrease levels of proinflammatory mediators.[

Very low toxicity of CBD in humans

Unlike the psychoactive properties associated with Δ9-THC, CBD has been shown to have very low toxicity in humans and in other species (see Safety section). Ingested and absorbed CBD is rapidly distributed, and due to its lipophilic nature can easily pass the blood–brain barrier. The terminal half-life of CBD is about 9 h and is preferentially excreted in the urine as its free and glucuronide form.[

Research on the endocannabinoid system

Research on the ECS is fervently ongoing with wide-ranging discoveries. The roles of endogenous cannabinoid, phytocannabinoids, and synthetic pharmacological agents acting on the various elements of the ECS have a potential to affect a wide range of pathologies, including food intake disorders, chronic pain, emesis, insomnia, glaucoma, gliomas, involuntary motor disorders, stroke, and psychiatric conditions such as depression, autism, and schizophrenia.[

The remaining sections will focus on the ECS and the effects of the phytocannabinoids, CBD and Δ9-THC, on neuroinflammation, neuroprotection, and their potential use in the treatment of specific neurological disorders including trauma involving the CNS.[

Neuroprotective benefits of phytocannabinoids

CBD research in animal models and humans has shown numerous therapeutic properties for brain function and protection, both by its effect on the ECS directly and by influencing endogenous cannabinoids. Broadly, CBD has demonstrated anxiolytic, antidepressant, neuroprotective antiinflammatory, and immunomodulatory benefits. CBD decreases the production of inflammatory cytokines, influences microglial cells to return to a ramified state, preserves cerebral circulation during ischemic events, and reduces vascular changes and neuroinflammation.[

Other effects of CBD

Other effects of CBD include the inhibition of calcium transport across membranes, the inhibition of anandamide uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis, and inhibition of inducible NO synthase protein expression and nuclear factor (NF)-κB activation. CBD increases brain adenosine levels by reducing adenosine reuptake. Increased adenosine is associated with neuroprotection and decreased inflammation after brain trauma.[

Experimental in vitro cannabinoid receptor interactions

Experimentally, in vitro, cannabinoid receptor interactions with CBD and Δ9-THC, together and separately, have demonstrated neuronal protection from excitotoxicity, hypoxia, and glucose deprivation; in vivo, cannabinoids decrease hippocampal neuronal loss and infarct volume after cerebral ischemia, acute brain trauma, and induced excitotoxicity. These effects have been ascribed to inhibition of glutamate transmission, reduction of calcium influx, reduced microglial activation, and subsequent inhibition of noxious cascades, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha generation and oxidative stress.[

Delta-9-THC

Δ9-THC can mediate the effects of the neurotransmitter serotonin by decreasing 5-HT3 receptor neurotransmission. This can contribute to the pharmacological action to reduce nausea. This effect can be reversed at higher doses or with chronic use of Δ9-THC.[

Brain neuroprotective effects of delta-9-THC

Δ9-THC has also been shown to protect the brain from various neuronal insults and improve the symptoms of neurodegeneration in animal models of MS, PD, HD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and AD.[

Neurodegenerative diseases

Overview

Neurodegenerative diseases include a large group of conditions associated with progressive neuronal loss leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. Histomorphological changes can include gliosis and proliferation of microglia along with aggregates of misfolded or aberrant proteins. The most common neurodegenerative conditions include AD, ALS, HD, Lewy body disease, and PD.

Numerous applications of CBD and delta-9-THC for neurodegenerative diseases

Numerous applications for CBD and Δ9-THC for neurodegenerative diseases are being evaluated for both symptom relief and as treatments for the underlying pathologic changes of neuronal tissue. Both CBD and Δ9-THC can function as agonist and antagonistic on various receptors in the ECS. In addition, a wide range of non-ECS receptors can be influenced by both endogenous and phytocannabinoids.[

Neuroprotection for AD

AD is characterized by enhanced beta-amyloid peptide deposition along with glial activation in senile plaques, selective neuronal loss, and cognitive deficits. Cannabinoids are neuroprotective against excitotoxicity in vitro and in patients with acute brain damage. In human AD patients, cellular studies of senile plaques have shown expression of cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, together with markers of microglial activation. Control CB1-positive neurons, however, are in greater numbers compared to AD areas of microglial activation. AD brains also have markedly decreased G-protein receptor coupling and CB1 receptor protein expression. Activated microglia cluster at senile plaques is generally believed to be responsible for the ongoing inflammatory process in the disease.

Research with administered cannabinoids for AD

Research with administered cannabinoids for AD in animals has demonstrated CB1 agonism is able to prevent tau hyperphosphorylation in cultured neurons and antagonize cellular changes and behavioral consequences in β-amyloid-induced rodents. CB2 antagonists were protective in in vivo experiments by downregulating reactive gliosis occurring in β-amyloid-injected animals. In addition, AD-induced microglial activation and loss of neurons was inhibited. AD-induced activation of cultured microglial cells, as judged by mitochondrial activity, cell morphology, and tumor necrosis factor release, is blunted by cannabinoid compounds.[

Cannabidiol

CBD is effective in an experimental model of Parkinsonism (6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats) by acting through antioxidant mechanisms independently of cannabinoid receptors.[

In rats lesioned with 3-nitropropionic acid, a toxin inhibitor of the mitochondrial citric acid cycle resulting in a progressive locomotor deterioration resembling that of HD patients, CBD reduces rat striatal atrophy in a manner independent of the activation of cannabinoid adenosine A2A receptors.[

CBD, and to a lesser degree Δ9-THC, can have both direct and indirect effects on isoforms of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs α, β, and γ). Activation of PPAR, along with CB1 and CB2, mediates numerous analgesic, neuroprotective, neuronal function modulation, antiinflammatory, metabolic, antitumor, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular effects, both in and outside the ECS. In addition, PPAR-γ (gamma) agonists have been used in the treatment of hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia. PPAR-γ decreases the inflammatory response of many cardiovascular cells, particularly endothelial cells, thereby reducing atherosclerosis. Phytocannabinoids can increase the transcriptional activity of and exert effects that are inhibited by selective antagonists of PPAR-γ, thus increasing production.[

CBD is further involved in the modulation of different receptors outside the ECS. The serotonin receptors have been implicated in the therapeutic effects of CBD. In a rat model, CBD was observed to stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuroprotective effects of CBD in hypoxic–ischemic brain damage model involve adenosine A2 receptors. CBD activation of adenosine receptors can enhance adenosine signaling to mediate antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. In a rat model of AD, CBD blunted the effects of reactive gliosis and subsequent β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity.

Delta-9-THC

In an animal model of AD, treatment with Δ9-THC (3 mg/kg) once daily for 4 weeks with addition of a COX-2 inhibitor reduced the number of beta-amyloid plaques and degenerated neurons. Δ9-THC has been used for AD symptom control. Treatment with 2.5 mg dronabinol (a synthetic analog of Δ9-THC) daily for 2 weeks significantly improved the neuropsychiatric inventory total score for agitation and aberrant motor and nighttime behaviors.[

Multiple sclerosis

CBD and delta-9-THC

MS is an autoimmune disease that promotes demyelination of neurons and subsequent aberrant neuronal firing that contributes to spasticity and neuropathic pain. The pathologic changes of MS include neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, demyelination, and neurodegeneration. These pathological features share similarities with other neurodegenerative conditions, including AD and cerebral ischemia. The combination of antiinflammatory, oligoprotective, and neuroprotective compounds that target the ECS may offer symptomatic and therapeutic treatment of MS.[

Use of cannabis-based medicine for neurodegenerative conditions

The use of cannabis-based medicine for the treatment of MS has a long history and its interaction with the ECS shares many of the same pathways of other neurodegenerative conditions.[

American Academy of Neurology statement on medical marijuana

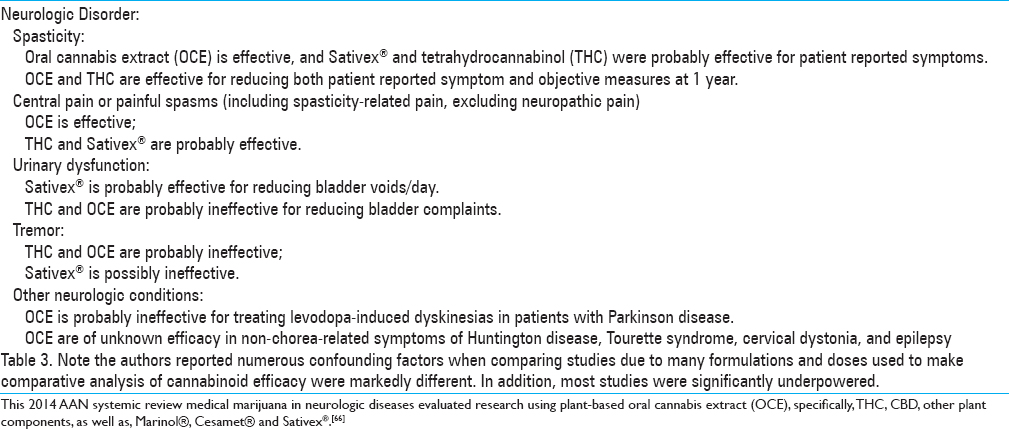

In 2014, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published a review article of 34 studies investigating the use of medical marijuana (as extracts, whole plants and synthetic phytocannabinoids) for possible neurological clinical benefits. They found strong support for symptoms of spasticity and spasticity-related pain, excluding neuropathic pain in the research using oral cannabis extracts. They reported inconclusive support for symptoms of urinary dysfunction, tremor, and dyskinesia. This study was subsequently used to form a consensus statement for their society. In the article they concluded their results based on the strength of the reported research [

Table 3

Conclusions from Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) systematic review on medical marijuana in neurologic diseases published in 2014[

MS animal models utilizing delta-9-THC

MS animal models using autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) have been used that demonstrate demyelination, neuroinflammation, and neurological dysfunction associated with infiltration of immune cells into the CNS consistent with the human disease. In certain types of mouse models of MS spasticity, Δ9-THC has been shown to ameliorate spasticity and tremors.[

Human trials using Δ9-THC for MS

Thus far, human trials with MS patients have been mixed using only 9-THC. In a 15-week trial with a tolerated dose of 9-THC, subjects had reduced urinary incontinence, and a 12-month follow-up demonstrated an antispasticity effect.[

CBD acts specifically to enhance adenosine signaling which increases extracellular adenosine, not AG-2. Neuroprotective effects of CBD in hypoxic–ischemic brain damage also involve adenosine A2 receptors. Specifically, CBD diminishes inflammation in acute models of injury and in a viral model of MS through adenosine A2 receptors.[

Positive human clinical trials by GW Pharmaceuticals have permitted the pharmaceutical, Sativex® to be marketed for MS spasticity in 16 countries outside the U.S. It is an oral-mucosal spray containing a 1:1 ratio of plant extracted Δ9-THC and CBD, having antispasmodic and analgesic properties shown to be effective for MS patients. The ability to modify pain may be attributed to a CB receptor-mediated regulation of supraspinal GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons. The results of these studies were cited in the AAN review.[

A meta-analysis in 2007 reported that CB receptor-based medications were superior to placebo in the treatment of MS-related neuropathic pain.[

Neuropsychiatric and brain trauma

Cannabidiol

CBD is recognized as a nonpsychoactive phytocannabinoid. Both human observational and animal studies, however, have demonstrated a broad range of therapeutic effects for several neuropsychiatric disorders. CBD has positive effects on attenuating psychotic, anxiety, and depressive-like behaviors. The mechanisms appear to be related to the CBD's benefit to provide enhanced neuroprotection and inhibition of excessive neuroinflammatory responses in neurodegenerative diseases and conditions. Common features involving neuroprotective mechanisms influenced by CBD—oxidative stress, immune mediators, and neurotrophic factors—are also important in conditions such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), postconcussion syndrome, depression, and anxiety. Many studies confirm that the function of the ECS is markedly increased in response to pathogenic events like trauma. This fact, as well as numerous studies on experimental models of brain trauma, supports the role of cannabinoids and their interactions with CB1 and CB2 as part of the brain's compensatory and repair mechanisms following injury. Animal studies indicate that posthead injury administration of exogenous CBD reduces short-term brain damage by improving brain metabolic activity, reducing cerebral hemodynamic impairment, and decreasing brain edema and seizures. These benefits are believed to be due to CBD's ability to increase anandamide.[

Treatment with CBD

Treatment with CBD may also decrease the intensity and impact of symptoms commonly associated with PTSD, including chronic anxiety in stressful environments.[

Antidepressant and neuroprotective properties

Antidepressants, used for the treatment of depression and some anxiety disorders, also possess numerous neuroprotective properties, such as preventing the formation of amyloid plaques, elevation of BDNF levels, reduction of microglia activation, and decreased levels of proinflammatory mediators.[

Rat models; efficacy of CBD in neurobehavioral disorders

In rat models of neurobehavioral disorders, CBD demonstrated attenuation of acute autonomic responses evoked by stress, inducing anxiolytic and antidepressive effects by activating 5HT1A receptors in a similar manner as the pharmaceutical buspirone that is approved for relieving anxiety and depression in humans.[

Human imaging studies correlated with CBD

Human imaging studies have demonstrated CBD affects brain areas involved in the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders. A study has showed that a single dose of CBD, administered orally in healthy volunteers, alters the resting activity in limbic and paralimbic brain areas while decreasing subjective anxiety associated with the scanning procedure.[

Tetrahydrocannabinol

Interestingly, THC, administered prior to a traumatic insult in human case studies and animal models has had measurable neuroprotective effects. In a 3-year retrospective study of patients who had sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI), decreased mortality was reported in individuals with a positive Δ9-THC screen. In mouse models of CNS injury, prior administration of Δ9-THC provided impairment protection.[

Anxiety relief in humans

For anxiety relief in humans, variability in the responses to cannabis depends on multiple factors, such as the relative concentrations of Δ9-THC and other phytocannabinoids. Studies have found Δ9-THC facilitates fear extinction.[

Cancer

CBD and THC

Cancer is a disease characterized by uncontrolled division of cells and their ability to spread. Novel anticancer agents are often tested for their ability to induce apoptosis and maintain steady-state cell population. In the early 1970s, phytocannabinoids were shown to inhibit tumor growth and prolong the life of mice with lung adenocarcinoma. Later studies have demonstrated cannabinoids inhibited tumor cell growth and induced apoptosis by modulating different cell signaling pathways in gliomas, lymphoma, prostate, breast, skin, and pancreatic cancer cells as well.[

Utility for glioblastoma multiforme

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most frequent class of malignant primary brain tumors. Both animal and human studies have demonstrated both Δ9-THC and CBD, combined and separately, have significant antitumor actions on GBM cancer cell growth. The mechanism of Δ9-THC antitumoral action is through ER stress-related signaling and upregulation of the transcriptional coactivators that promote autophagy.[

CBD reduces growth different tumor xenografts

CBD has also been shown to reduce the growth of different types of tumor xenografts including gliomas. The mechanism of action of CBD is thought to be increased production of ROS in glioma cells, thereby inducing cytotoxicity or apoptosis and autophagy.[

In Feb 2017, GW Pharmaceuticals announced positive results from a phase 2 placebo-controlled clinical study of their proprietary drug combining of Δ9-THC and CBD in 21 patients with recurrent GBM. The results showed 83% one-year treatment group survival rate compared with 53% for patients in the placebo cohort (P = 0.042). Median survival was greater than 550 days compared with 369 days in the placebo group. GW Pharmaceuticals has subsequently received Orphan Drug Designation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for their Δ9-THC and CBD combination for the treatment of malignant glioma.[

Intractable epilepsy

Cannabidiol

Reports of cannabis use in the treatment of epilepsy appear as far back as 1800 BC. Scientific reports appear in 1881 from neurologists using Indian hemp to treat epilepsy with dramatic success.[

Experiments with Δ9-THC have demonstrated a rebound hyperexcitability in the CNS in mice, with enhanced neuronal excitability and increased sensitivity to convulsions and has not been used on most trials of intractable epilepsy. CBD, however, produces antiepileptiform and anticonvulsant effects in both in vitro and in vivo models.[

More recently in 1980, Cunha et al., published a double-blind study that evaluated CBD for intractable epilepsy in 16 patients with grand-mal seizures. Each patient received 200–300 mg daily of CBD or placebo along with antiepileptic drugs for up to 4 months.[

As with most cannabinoid research to date, conducting studies can be difficult due to limited legal access to medical grade marijuana and phytocannabinoid extracts. Hemp-derived CBD, however, has recently experienced less regulation and as a result research using CBD for refractory epilepsy has experienced a resurgence.

CBDs reduce neuronal hyperactivity in epilepsy

CBD's overall effect appears to result in reduction of neuronal hyperactivity in epilepsy.[

Endogenous cannabinoids

Endogenous cannabinoids appear to affect the initiation, propagation, and spread of seizures. Studies have identified defects in the ECS in some patients with refractory seizure disorders, specifically having low levels of anandamide and reduced numbers of CB1 receptors in CSF and tissue biopsy.[

The pharmaceutical company, GW Pharmaceuticals, is currently developing the CBD drug, Epidiolex® that is a purified, 99% oil-based CBD extract from the cannabis plant. Results of a recent 2015 open-label study (without a placebo control) in 137 people with treatment-resistant epilepsy indicated that 12 weeks of Epidiolex® reduced the median number of seizures by 54%.[

Despite the preclinical data by GW Pharmaceutical and anecdotal reports on the efficacy of cannabis in the treatment of epilepsy, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “no reliable conclusions can be drawn at present regarding the efficacy of cannabinoids as a treatment for epilepsy.” This report noted this conclusion was mostly due to the lack of adequate data from randomized, controlled trials of Δ9-THC, CBD, or any other cannabinoid in combination.[

Safety

A comprehensive safety and side effect review of CBD in 2016 on both animal and human studies described an excellent safety profile of CBD in humans at a wide variety of doses. The most commonly reported side effects were tiredness, diarrhea, and changes of appetite/weight.[

CBD – better safety profile vs. other cannabinoids

CBD also has a better safety profile compared to other cannabinoids, such as THC. For instance, high doses of CBD (up to 1500 mg/day) are well tolerated in animals and humans. In contrast to THC, CBD does not alter heart rate, blood pressure, or body temperature, does not induce catalepsy, nor alter psychomotor or psychological functions.[

Synthetic analog nabilone

A synthetic analog of Δ9-THC, nabilone (Cesamet™; Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America), was approved in 1981 for the suppression of the nausea and vomiting produced by chemotherapy. Synthetic Δ9-THC, dronabinol (Marinol®; Solvay Pharmaceuticals), was subsequently licensed in 1985 as an antiemetic and in 1992 as appetite stimulant. The capability of Δ9-THC for stimulating the CB1 receptor is paradoxically both the main reason for, and drawback against, its therapeutic use. In fact, as discussed below, psychotropic effects, and the potential risk of cardiac side effects, tolerance, and dependence, limit the application of Δ9-THC as a synthetic or from a plant source in many therapeutic applications.[

Adverse effects

The 2014 AAN review of 34 articles on MS using cannabinoids of various forms noted several adverse effects. Reported symptoms included nausea, increased weakness, behavioral or mood changes (or both), suicidal ideation or hallucinations, dizziness or vasovagal symptoms (or both), fatigue, and feelings of intoxication. Psychosis, dysphoria, and anxiety were associated with higher concentrations of THC. However, no direct fatalities or overdoses have been attributed to marijuana, even in recreational users of increasingly potent marijuana possibly due to lack of endocannabinoid receptors in the brainstem.[

In a recent rule change by the World Anti-Doping Agency or WADA, CBD will no longer be listed as a banned substance for international sport competition for 2018. The agency noted that Δ9-THC will still be prohibited. WADA issued with this ruling that noted CBD extracted from cannabis plants still may contain varying concentrations of THC.[

Dosing

It is beyond the scope of this review to provide any meaningful dosing recommendations for CBD or Δ9-THC. Like other cannabinoids, CBD produces bell-shaped dose–response curves and can act by different mechanisms according to its concentration or the simultaneous presence of other cannabinoid-ligands.[

Prescribing medical marijuana

Ultimately, prescribing medical marijuana either as a primary treatment or adjunctive therapy will require extreme care and knowledge about the patient's goals and expectations for treatment. States that have allowed medical marijuana have generally required competency trainings and certification prior to prescribing. There are general screening questions that should be considered before recommending marijuana to a patient. At minimum, these questions should include the following:[

Is there documentation that the patient has had failure of all other conventional medications to treat his or her ailment? Have you counseled the patient (documented by the patient's signed informed consent) regarding the medical risks of the use of marijuana—medical, psychological, and social (such as impairment of driving or work skills) and habituation? Does your patient have a history of misused marijuana or other psychoactive, addictive prescription and illegal drugs? Will you want periodic drug testing? Will you know the standardization and potency content of the medical marijuana to be used and whether it is free of contaminants?

FDA approvals

The FDA has approved the synthetic drugs Cesamet®, Marinol®, and Syndros® for therapeutic uses in the U.S. FDA-posted indications include nausea and the treatment of anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients. Marinol® and Syndros® include the active ingredient dronabinol, a synthetic delta-9-THC. Cesamet® contains the active ingredient nabilone that has a chemical structure similar to THC and is also synthetically derived. Although these medications are often cited in human clinical research, their general use is limited based both on side effects and indication constraints.

CONCLUSION

Although federal and state laws are inconsistent about the legality of cannabis production, its increasingly documented health benefits make it once again relevant in medicine. Current research indicates the phytocannabinoids have a powerful therapeutic potential in a variety of ailments primarily through their interaction with the ECS. CBD is of particular interest due to its wide-ranging capabilities and lack of side effects in a variety of neurological conditions and diseases.

Legalization of marijuana in many states: Need for education

Because of the rapid legalization of medical marijuana by the majority of state legislatures in the U.S., physicians are faced with a lack of formal education and basic knowledge as to the possible indications, side effects, interactions, and dosing when prescribing medical marijuana. Because of federal restrictions on human research in the U.S., we lack the number and quality of human trials typically used when prescribing a medication. This review of the neurological benefits of phytocannabinoids has demonstrated significant benefits for neuroprotection and disease reductions in a wide variety of neurological diseases and conditions in humans.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The Authors report the following conflicts: University of Pittsburgh Medical Center - Employer, National Football League – Medical Consultant – Non-paid consultant, Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club – Medical Consultant – Non-paid consultant, World Wrestling Entertainment Corporation – Paid Consultant, ImPACT Applications, INC (Immediate Post Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing) – Shareholder, Board Member, CV Sciences - Shareholder.

Acknowledgment

Dennis and Rose Heindl, Nelson and Claudia Peltz Mylan Labs Foundations, Lewis Topper, Shirley Mundel, John and Cathy Garcia and the Neuroscience Research foundation.

References

1. Abush H, Akirav I. Cannabinoids Ameliorate Impairments Induced by Chronic Stress to Synaptic Plasticity and Short-Term Memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013. 38: 1521-34

2. Aso E, Juves S, Maldonado R, Ferrer I. CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonist ameliorates Alzheimer-like phenotype in A beta PP/PS1 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013. 35: 847-58

3. Baker D, Pryce G, Croxford JL, Brown P, Pertwee RG, Huffman JW. Cannabinoids control spasticity and tremor in a multiple sclerosis model. Nature. 2000. 404: 84-7

4. Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RH, Zuardi AW, Crippa AJ. Safety and side effects of cannabidiol: A Cannabis sativa constituent. Curr Drug Saf. 2011. 6: 237-49

5. Bergamaschi MM, Queiroz RHC, Chagas MHN, de Oliveira DCG, De Martinis BS, Kapczinski F. Cannabidiol reduces the anxiety induced by simulated public speaking in treatment-naive social phobia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011. 36: 1219-26

6. Bih CI, Chen T, Nunn AV, Bazelot M, Dallas M, Whalley BJ. Molecular targets of cannabidiol in neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2015. 12: 699-730

7. Borea PA, Gessi S, Merighi S, Vincenzi F, Varani K. Pathological overproduction: The bad side of adenosine. Br J Pharmacol. 2017. 174: 1945-60

8. Bredt DS, Furey ML, Chen G, Lovenberg T, Drevets WC, Manji HK. Translating depression biomarkers for improved targeted therapies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015. 59: 1-15

9. Brown AJ. Novel cannabinoid receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2007. 152: 567-75

10. Campos AC, Fogaça MV, Scarante FF, Joca SRL, Sales AJ, Gomes FV. Plastic and neuroprotective mechanisms involved in the therapeutic effects of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2017. 8: 269-

11. Campos AC, Moreira FA, Gomes FV, Del Bel EA, Guimarães FS. Multiple mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol in psychiatric disorders. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012. 367: 3364-78

12. Camposa AC, Fogac MV, Sonegoa AB, Guimarãesa FS. Cannabidiol, neuroprotection and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2016. 112: 119-27

13. Carracedo A, Gironella M, Lorente M, Garcia S, Guzman M, Velasco G. Cannabinoids induce apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. Cancer Res. 2006. 66: 6748-55

14. Carracedo A, Lorente M, Egia A, Blazquez C, Garcia S, Giroux V. The stress-regulated protein p8 mediates cannabinoid-induced ptosis of tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2006. 9: 301-12

15. Cassan C, Liblau RS. Immune tolerance and control of CNS autoimmunity: From animal models to MS patients. J Neurochem. 2007. 100: 883-92

16. Castillo A, Tolóna MR, Fernández-Ruizb , J , Romeroa J, Martinez-Orgadoa J. The neuroprotective effect of cannabidiol in an in vitro model of newborn hypoxic–ischemic brain damage in mice is mediated by CB2 and adenosine receptors. Neurobiol Dis. 2010. 37: 434-40

17. Castren E. Neuronal network plasticity and recovery from depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013. 70: 983-9

18. Centonze D, Bari M, Rossi S, Prosperetti C, Furlan R, Fezza F. The endocannabinoid system is dysregulated in multiple sclerosis and in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain. 2007. 130: 2543-53

19. Chen RQ, Zhang J, Fan N, Teng ZQ, Wu Y, Yang HW. Delta(9)-THC-caused synaptic and memory impairments are mediated through COX-2 signaling. Cell. 2013. 155: 1154-65

20. Consroe P, Benedito MA, Leite JR, Carlini EA, Mechoulam R. Effects of cannabidiol on behavioral seizures caused by convulsant drugs or current in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982. 83: 293-8

21. Consroe P, Laguna J, Allender J, Snider S, Stern L, Sandyk R. Controlled clinical trial of cannabidiol in Huntington's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991. 40: 701-8

22. Consroe P, Musty R, Rein J, Tillery W, Pertwee R. The perceived effects of smoked cannabis on patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 1997. 38: 44-8

23. Consroe P, Sandyk R, Snider SR. Open label evaluation of cannabidiol in dystonic movement disorders. Int J Neurosci. 1986. 30: 277-82

24. Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Garrido GE, Wichert-Ana L, Guarnieri R, Ferrari L. Effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on regional cerebral blood flow. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004. 29: 417-26

25. Cunha JM, Carlini EA, Pereira AE, Ramos OL, Pimentel G, Gagliardi . Chronic administration of cannabidiol to healthy volunteers and epileptic patients. Pharmacology. 1980. 21: 175-85

26. De Petrocellis L, Ligresti A, Schiano Moriello A, Iappelli M, Verde R, Stott CG. Non-THC cannabinoids inhibit prostate carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo: Pro-apoptotic effects and underlying mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2013. 168: 79-102

27. Deshpande LS, Blair RE, Ziobro JM, Sombati S, Martin BR, DeLorenzo RJ. Endocannabinoids block status epilepticus in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007. 558: 52-9

28. Devinsky O, Cilio MR, Cross H, Fernandez-Ruiz J, French J, Hill C. Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and potential therapeutic role in epilepsy and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Epilepsia. 2014. 55: 791-802

29. Devinsky O, Marsh E, Friedman D, Thiele E, Laux L, Sullivan J. Cannabidiol in patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: An open-label interventional trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016. 15: 270-8

30. Devinsky O, Cross JH, Laux L, Marsh E, Miller I, Nabbout R. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017. 376: 2011-20

31. Esposito G, De Filippis D, Steardo L, Scuderi C, Savani C, Cuomo V. CB1 receptor selective activation inhibits beta-amyloid-induced iNOS protein expression in C6 cells and subsequently blunts tau protein hyperphosphorylation in co-cultured neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2006. 404: 342-6

32. Esposito G, Scuderi C, Savani C, Steardo L, De Filippis D, Cottone P. Cannabidiol in vivo blunts beta-amyloid induced neuroinflammation by suppressing IL-1ß and iNOS expression. Br J Pharmacol. 2007. 151: 1272-9

33. Esposito G, Scuderi C, Valenza M, Togna GI, Latina V. Cannabidiol reduces ab-induced neuroinflammation and promotes hippocampal neurogenesis through PPARc involvement. PLoS One. 2011. 6: e28668-

34. Fellermeier M, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk MH. Biosynthesis of cannabinoids. Eur J Biochem. 2001. 268: 1596-604

35. Fernandez-Ruiz J, Moreno-Martet M, Rodriguez-Cueto C, Palomo-Garo C, Gomez-Canas M, Valdeolivas S. Prospects for cannabinoid therapies in basal ganglia disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2011. 163: 1365-78

36. Freeman RM, Adekanmi O, Waterfield MR, Waterfield AE, Wright D, Zajicek J. The effect of cannabis on urge incontinence in patients with multiple sclerosis: A multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled trial (CAMS-LUTS). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006. 17: 636-41

37. Freund TF, Katona I, Piomelli D. Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev. 2003. 83: 1017-66

38. Friedman D, Devinsky O. Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2015. 373: 1048-58

39. Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Bhattacharyya S, Borgwardt SJ, Allen P, Martin-Santos R. Distinct effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on neural activation during emotional processing. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009. 66: 95-105

40. Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Isolation structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J Am Chem Soc. 1964. 86: 1646-7

41. Garcia-Arencibia M, Gonzalez S, de Lago E, Ramos JA, Mechoulam R, Fernandez-Ruiz J. Evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson's disease: Importance of antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent properties. Brain Res. 2007. 1134: 162-70

42. Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL.editors. Cannabinoid receptors in the human brain: a detailed anatomical and quantitative autoradiographic study in the fetal, neonatal and adult human brain. Neuroscience. 1997. 77: 299-318

43. Gloss D, Vickrey B. Cannabinoids for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014. 3: CD009270-

44. Gowran A, Noonan J, Campbell VA. The multiplicity of action of cannabinoids: Implications for treating neurodegeneration. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011. 17: 637-44

45. Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. The use of cannabis as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder: Anecdotal evidence and the need for clinical research. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998. 30: 171-7

46. Guo J, Ikeda SR. Endocannabinoids modulate N-type calcium channels and G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels via CB1 cannabinoid receptors heterologously expressed in mammalian neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2004. 65: 665-74

47. Last accessed on 2018 Jan 29. Available from: https://www.gwpharm.com/about-us/news/gw-pharmaceuticals-achieves-positive-results-phase-2-proof-concept-study-glioma/.

48. Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Axelrod J, Wink D. Cannabidiol and (-)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998. 95: 8268-73

49. Hanuš LO, Meyer SM, Muñoz E, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Appendino G. Phytocannabinoids: A unified critical inventory. Nat Prod Rep. 2016. 33: 1357-

50. Hermann D, Schneider M. Potential protective effects of cannabidiol on neuroanatomical alterations in cannabis users and psychosis: A critical review. Curr Pharm Des. 2012. 18: 4897-905

51. Hill AJ, Williams CM, Whalley BJ, Stephens GJ. Phytocannabinoids as novel therapeutic agents in CNS disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2012. 133: 79-97

52. Hill KP. Medical marijuana for treatment of chronic pain and other medical and psychiatric problems: A clinical review. JAMA. 2015. 313: 2474-83

53. Hillard CJ. Endocannabinoids and vascular function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000. 294: 27-32

54. Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002. 54: 161-202

55. Huntley A. A review of the evidence for efficacy of complementary and alternative medicines in MS. Int MS J. 2006. 13: 5-12

56. Iannotti FA, Hill CL, Leo A, Alhusaini A, Soubrane C, Mazzarella E. Nonpsychotropic plant cannabinoids, cannabidivarin (CBDV) and cannabidiol (CBD), activate and desensitize transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channels in vitro: Potential for the treatment of neuronal hyperexcitability. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014. 5: 1131-41

57. Iffland K, Grotenhermen F.editors. European Industrial Hemp Association (EIHA) review on: Safety and Side Effects of Cannabidiol– A review of clinical data and relevant animal studies. Germany: Hürth; 2016. p.

58. Iskedjian M, Bereza B, Gordon A, Piwko C, Einarson TR. Meta-analysis of cannabis based treatments for neuropathic and multiple sclerosis-related pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007. 23: 17-24

59. Iuvone T, Esposito G, Esposito R, Santamaria R, Di Rosa M, Izzo AA. Neuroprotective effect of cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive componentpCannabis sativa, on ß-amyloid-induced toxicity in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 2004. 89: 134-41

60. Iuvone T, Esposito G, De Filippis D, Scuderi C, Steardo L. Cannabidiol: A promising drug for neurodegenerative disorders?. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009. 15: 65-75

61. Jones NA, Glyn SE, Akiyama S, Hill TDM, Hill AJ, Weston SE. Cannabidiol exerts anti-convulsant effects in animal models of temporal lobe and partial seizures. Seizure-Eur J Epilepsy. 2012. 21: 344-52

62. Jones NA, Hill AJ, Smith I, Bevan SA, Williams CM, Whalley BJ. Cannabidiol displays antiepileptiform and antiseizure properties in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010. 332: 569-77

63. Kapur A, Zhao PW, Sharir H, Bai YS, Caron MG, Barak LS. A typical responsiveness of the orphan receptor GPR55 to cannabinoid ligands. J Biol Chem. 2009. 284: 29817-27

64. Karler R, Calder LD, Turkanis SA. Prolonged CNS hyperexcitability in mice after a single exposure to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Neuropharmacology. 1989. 25: 441-6

65. Kim D, Thayer SA. Cannabinoids Inhibit the Formation of New Synapses between Hippocampal Neurons in Culture. J Neurosci. 2001. 21: RC146-

66. Koppel BS, Brust JCM, Fife T, Bronstein J, Youssof S, Gronseth G. Systematic review: Efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders, Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014. 82: 1556-63

67. Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC. Dopamine modulation of state-dependent endocannabinoid release and long-term depression in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2005. 25: 10537-45

68. Lafourcade M, Elezgarai I, Mato S, Bakiri Y, Grandes P, Manzoni OJ. Molecular Components and Functions of the Endocannabinoid System in Mouse Prefrontal Cortex. PLoS One. 2007. 2: e709-

69. Leweke FM, Piomelli D, Pahlisch F, Muhl D, Gerth CW, Hoyer C. Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2012. 2: e94-

70. Ligresti A, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V. From phytocannabinoids to cannabinoid receptors and endocannabinoids: Pleiotropic physiological and pathological roles through complex pharmacology. Physiol Rev. 2016. 96: 1593-659

71. Ligresti A, Schiano Moriello A, Starowicz K, Matias I, Pisanti S, De Petrocellis L. Antitumor activity of plant cannabinoids with emphasis on the effect of cannabidiol on human breast carcinoma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006. 318: 1375-87

72. Loria F, Petrosino S, Hernangómez M, Mestre M, Spagnolo A, Correa F. An endocannabinoid tone limits excitotoxicity in vitro and in a model of multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2010. 37: 166-76

73. Maresz K, Carrier EJ, Ponomarev ED, Hillard CJ, Dittel BN. Modulation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in microglial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli. J Neurochem. 2005. 95: 437-45

74. Massi P, Vaccani A, Bianchessi S, Costa B, Macchi P, Parolaro D. The non-psychoactive cannabidiol triggers caspase activation and oxidative stress in human glioma cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006. 63: 2057-66

75. Mato S, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Matute C. Cannabidiol induces intracellular calcium elevation and cytotoxicity in oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2010. 58: 1739-47

76. McAllister SD, Murase R, Christian RT, Lau D, Zielinski AJ, Allison J. Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011. 129: 37-47

77. McHugh D, Page J, Dunn E, Bradshaw HB. Delta(9)-Tetrahydrocannabinol and N-arachidonyl glycine are full agonists at GPR18 receptors and induce migration in human endometrial HEC-1B cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2012. 165: 2414-24

78. Mecha M, Feliú A, Carrillo-Salinas F, Guaza CHandbook of Cannabis and Related Pathologies. Elsevier; 2017. p. 893-904

79. Mecha M, Torrao AS, Mestre L, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Mechoulam R, Guaza C. Cannabidiol protects oligodendrocyte progenitor cells from inflammation-induced apoptosis by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Dis. 2012. 3: e331-

80. Mechoulam R, Braun P, Gaoni YA. Stereospecific synthesis of (-)-delta 1- and (-)-delta 1(6)-tetrahydrocannabinols. J Am Chem Soc. 1967. 89: 4552-4

81. Mechoulam R, Shvo Y, Hashish I. The structure of cannabidiol. Tetrahedron. 1963. 19: 2073-8

82. Nestler EJ, Barrot M, DiLeone RJ, Eisch AJ, Gold SJ, Monteggia LM. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron. 2002. 34: 13-25

83. Oakley JC, Kalume F, Catterall WA. Insights into pathophysiology and therapy from a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. 2011. 52: 59-61

84. Pagotto U, Marsicano G, Cota D, Lutz B, Pasquali R. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr Rev. 2006. 27: 73-100

85. Pertwee R. Pharmacological and therapeutic targets for Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Euphytica. 2004. 140: 73-

86. Pertwee RG. Pharmacology of Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 Receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 1997. 74: 129-80

87. Pertwee RG. Emerging strategies for exploiting cannabinoid receptor agonists as medicines. Br J Pharmacol. 2009. 156: 397-411

88. Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol. 2008. 153: 199-215

89. Pettit DAD, Harrison MP, Olson JM, Spencer RF, Cabral GA. Immunohistochemical localization of the neural cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. J. Neurosci Res. 1998. 51: 391-402

90. Portella G, Laezza C, Laccetti P, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V, Bifulco M. Inhibitory effects of cannabinoid CB1 receptor stimulation on tumor growth and metastatic spreading: Actions on signals involved in angiogenesis and metastasis. FASEB J. 2003. 17: 1771-3

91. Rabinak CA, Angstadt M, Sripada CS, Abelson JL, Liberzon I, Milad MR. Cannabinoid facilitation of fear extinction memory recall in humans. Neuropharmacology. 2013. 64: 396-402

92. Ramirez BG, Blazquez C, Gomez del Pulgar T, Guzman M, de Ceballos ML. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease pathology by cannabinoids: Neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2005. 25: 1904-13

93. Rea K, Roche M, Finn DP. Supraspinal modulation of pain by cannabinoids: The role of GABA and glutamate. Br J Pharmacol. 2007. 152: 633-48

94. Rog DJ, Nurmikko TJ, Young CA. Oromucosal, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol for neuropathic pain associated with multiple sclerosis: An uncontrolled, open-label, 2-year extension trial. Clin Ther. 2007. 29: 2068-79

95. Rog DJ, Nurmikko TJ, Friede T, Young CA. Randomized, controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in central pain in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005. 65: 812-9

96. Roitman P, Mechoulam R, Cooper-Kazaz R, Shalev A. Preliminary, open-label, pilot study of add-on oral δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Clin Drug Investig. 2014. 34: 587-91

97. Romigi A, Bari M, Placidi F, Marciani MG, Malaponti M, Torelli F. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are reduced in patients with untreated newly diagnosed temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2010. 51: 768-72

98. Ronesi J, Lovinger DM. Induction of striatal long-term synaptic depression by moderate frequency activation of cortical afferents in rat. J Physiol. 2005. 562: 245-56

99. Sagredo O, Gonzalez S, Aroyo I, Pazos MR, Benito C, Lastres-Becker I. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonists protect the striatum against malonate toxicity: Relevance for Huntington's disease. Glia. 2009. 57: 1154-67

100. Sagredo O, Ramos JA, Decio A, Mechoulam R, Fernandez-Ruiz J. Cannabidiol reduced the striatal atrophy caused 3-nitropropionic acid in vivo by mechanisms independent of the activation of cannabinoid, vanilloid TRPV1 and adenosine A2A receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2007. 26: 843-51

101. Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Egia A, Lorente M. TRB3 links ER stress to autophagy in cannabinoid anti-tumoral action. Autophagy. 2009. 5: 1048-9

102. Salazar M, Carracedo A, Salanueva IJ, Hernandez-Tiedra S, Lorente M, Egia A. Cannabinoid action induces autophagy-mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells. J Clin Invest. 2009. 119: 1359-72

103. Sano K, Mishima K, Koushi E, Orito K, Egashira N, Irie K. Delta(9)- tetrahydrocannabinol-induced catalepsy-like immobilization is mediated by decreased 5-HT neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens due to the action of glutamate-containing neurons. Neuroscience. 2008. 151: 320-8

104. Schultes RE. Man and marijuana. Nat Hist. 1973. 82: 59-

105. Schultes RE. Hallucinogens of Plant Origin.Science. 1969. 163: 245-54

106. Schurman LD, Lichtman AH. Endocannabinoids: A promising impact for traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol. 2017. 8: 69-

107. Shah A, Carreno FR, Frazer A. Therapeutic modalities for treatment resistant depression: Focus on vagal nerve stimulation and ketamine. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2014. 12: 83-93

108. Sheline YI, West T, Yarashesk KI, Swarm R, Jasielec MS, Fisher JR. An antidepressant decreases CSF Abeta production in healthy individuals and in transgenic AD mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014. 6: 236re4-

109. Shohami E, Cohen-Yeshurun A, Magid L, Algali M, Mechoulam R. Endocannabinoids and traumatic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2011. 163: 1402-10

110. Singer E, Judkins J, Salomonis N, Matlaf L, Soteropoulos P, McAllister S. Reactive oxygen species-mediated therapeutic response and resistance in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015. 6: e1601-

111. Solinas M, Massi P, Cantelmo AR, Cattaneo MG, Cammarota R, Bartolini D. Cannabidiol inhibits angiogenesis by multiple mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2012. 167: 1218-31

112. Stern CAJ, Gazarini L, Vanvossen AC, Zuardi AW, Galve-Roperh I, Guimaraes FS. Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol alone and combined with cannabidiol mitigate fear memory through reconsolidation disruption. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015. 25: 958-65

113. Stern CA, Gazarini L, Takahashi RN, Guimarães FS, Bertoglio LJ. On disruption of fear memory by reconsolidation blockade: Evidence from cannabidiol treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012. 37: 2132-42

114. Uribe-Mariño A, Francisco A, Castiblanco-Urbina MA, Twardowschy A, Salgado-Rohner CJ, Crippa J. Anti-Aversive Effects of Cannabidiol on Innate Fear-Induced Behaviors Evoked by an Ethological Model of Panic Attacks Based on a Prey vs the Wild Snake Epicrates cenchria crassus Confrontation Paradigm. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012. 37: 412-21

115. Valdeolivas S, Satta V, Pertwee RG, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Sagredo O. Sativex-like combination of phytocannabinoids is neuroprotective in malonate-lesioned rats, an inflammatory model of Huntington's disease: Role of CB1 and CB2 receptors. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012. 3: 400-6

116. Van Der Stelt M, Mazzola C, Esposito G, Matias I, Petrosino S, De Filippis D. Endocannabinoids and beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in vivo: Effect of pharmacological elevation of endocannabinoid levels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006. 63: 1410-24

117. Velenovská M, Fisar Z. Effect of cannabinoids on platelet serotonin uptake. Addict Biol. 2007. 12: 158-66

118. Voth EA. Guidelines for prescribing medical marijuana. West J Med. 2001. 175: 305-6

119. Last accessed on 2018 Jan 29. Available from: https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/prohibited_list_2018_en.pdf.

120. Wade DT, Makela P, Robson P, House H, Bateman C. Do cannabis-based medicinal extracts have general or specific effects on symptoms in multiple sclerosis? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study on 160 patients. Mult Scler. 2004. 10: 434-41

121. Walther S, Mahlberg R, Eichmann U, Kunz D. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for nighttime agitation in severe dementia. Psychopharmacology. 2006. 185: 524-8

122. Wang Q, Shao F, Wang W. Maternal separation produces alterations of forebrain brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in differently aged rats. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015. 8: 49-

123. Wee N, Kandiah N, Acharyya S, Chander RJ, Ng A, Au WL. Depression and anxiety are co-morbid but dissociable in mild Parkinson's disease: A prospective longitudinal study of patterns and predictors. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016. 23: 50-6

124. Whalley BJ. Cannabis in the Management and Treatment of Seizures and Epilepsy: A Scientific Review Pre-publication release for public domain dissemination. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 2014. p.

125. Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signaling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001. 410: 588-92

126. Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, Wright D, Vickery J, Nunn A. Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003. 362: 1517-26

127. Zajicek JP, Sanders HP, Wright DE, Vickery PJ, Ingram WM, Reilly SM. Cannabinoids in multiple sclerosis (CAMS) study: Safety and efficacy data for 12 months follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005. 76: 1664-9

128. Zhang K, Jiang H, Zhang Q, Du J, Wang Y, Zhao M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum levels in heroin-dependent patients after 26 weeks of withdrawal. Compr Psychiatry. 2016. 65: 150-5

129. Zhornitsky S, Potvin S. Cannabidiol in Humans—The Quest for Therapeutic Targets. Pharmaceuticals. 2012. 5: 529-52