- Department of Neurosurgery, Fukuoka University Hospital and School of Medicine, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Okinawa Miyako Hospital, Okinawa, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Satoshi Yamamoto

Department of Neurosurgery, Okinawa Miyako Hospital, Okinawa, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_66_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Naoki Wakuta, Satoshi Yamamoto. Risk of fatal sinus arrest induced by low-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case of a young patient with obstructive sleep apnea. 20-Jun-2020;11:156

How to cite this URL: Naoki Wakuta, Satoshi Yamamoto. Risk of fatal sinus arrest induced by low-grade subarachnoid hemorrhage: A case of a young patient with obstructive sleep apnea. 20-Jun-2020;11:156. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10092/

Abstract

Background: Sleep apnea syndrome (SAS) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are both considered possible causes of secondary arrhythmias. However, there are limited reports on the increased risk of bradyarrhythmia for arrhythmia-free SAS patients with SAH.

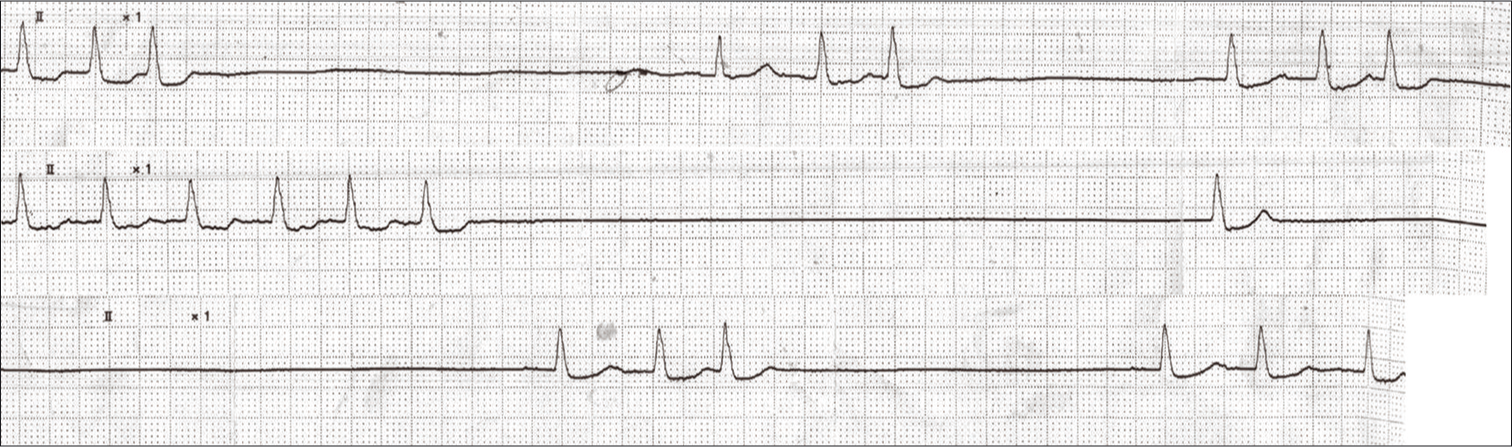

Case Description: A 31-year-old woman with SAS developed low-grade SAH and underwent coil embolization on postbleed day 1. Following a coiling procedure, she experienced worsening episodes of sinus arrest lasting up to 12 s and required a temporary pacemaker. Frequent episodes of sinus arrest were detected for the next 4 days. Thereafter, all types of arrhythmias gradually decreased, and she eventually recovered to be arrhythmia free.

Conclusion: Acceleration of sympathetic nervous activity caused by acute SAH may predispose patients to bradyarrhythmia with SAS and elicit asystole. The coexistence of SAS and SAH should be recognized as a cause of life-threatening sinus arrest, even if the severity of SAH is low grade.

Keywords: Endovascular surgery, Sinus arrest, Sleep apnea syndrome, Subarachnoid hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

Potential cardiac abnormalities with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (SAS), including arrhythmias and ischemic heart disease, have been previously reported. An increased risk of complicated cardiac or lung disease in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) has also been described. The greater the severity of SAH and SAS, the greater the number and severity of associated complications.[

CASE REPORT

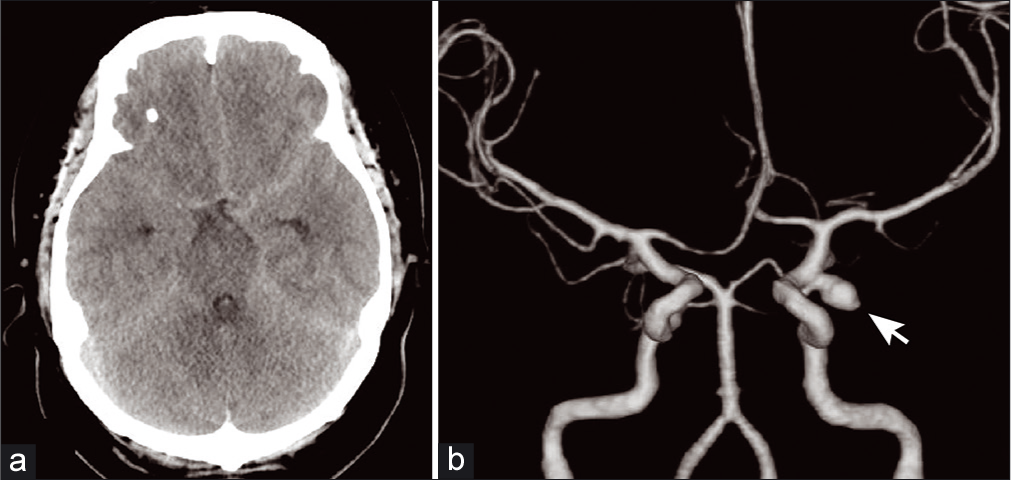

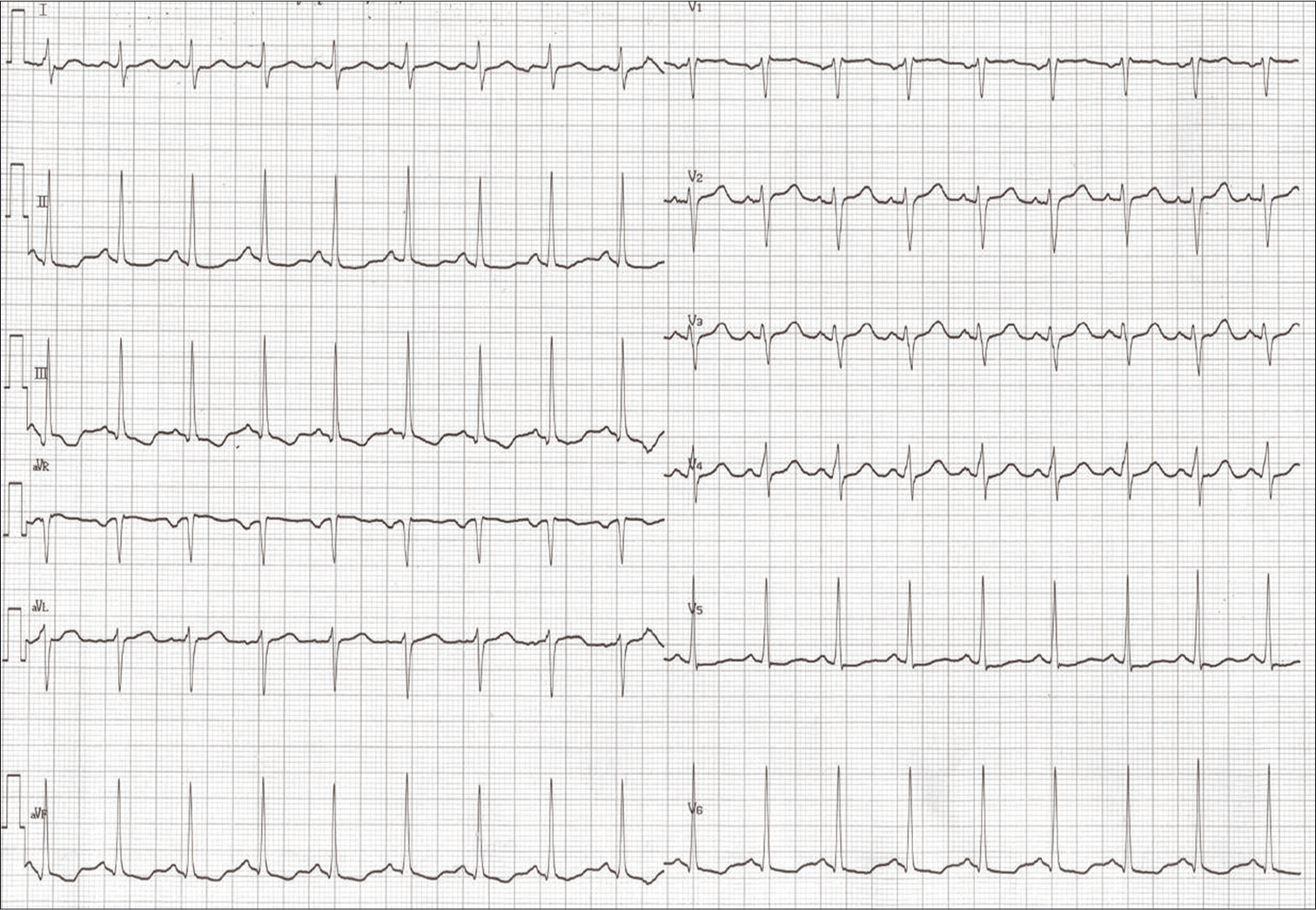

The patient was an obese 31-year-old woman (body mass index: 43.7 kg/m2). She was examined at our hospital laboratory 1-year before severe SAS, with 132 episodes of apnea/hour and significant hypoxia in polysomnography. A 24-h electrocardiogram (ECG) detected an inverted T wave, but no arrhythmias. She denied a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia. She had no habit of smoking or a family history of SAH or intracranial aneurysm. She presented with a worsening headache, but was alert and oriented, with no neurological deficit (World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies [WFNS] Grade 1). Head computed tomography revealed SAH, and computed tomography arteriogram showed a carotid-posterior communicating artery aneurysm with a bleb [

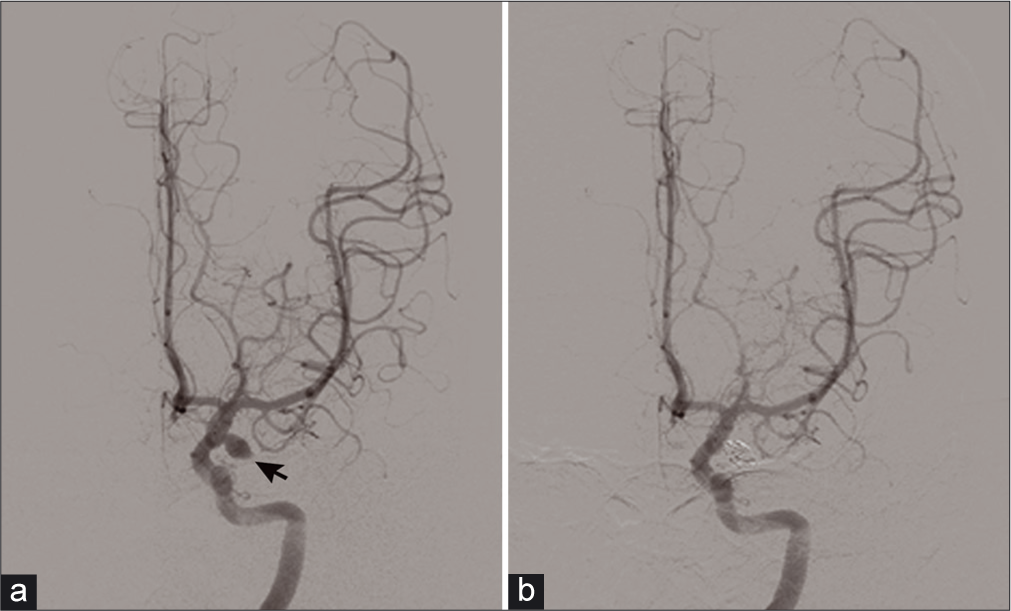

The patient agreed to endovascular treatment to prevent rebleeding, and coil embolization for the ruptured aneurysm was performed under general anesthesia on postbleed day (PBD 1) [

DISCUSSION

Cardiac abnormalities are very common in patients with acute SAH and include electrocardiographic abnormalities,[

Several studies have reported the risk factors for complicated arrhythmias in SAH, which include age >53 years,[

Our case was a young woman without any medical history apart from SAS. Her recent examination for SAS and associated arrhythmia did not detect any bradyarrhythmia during the day or night. Her SAH was low grade (WFNS Grade 1), although she experienced life-threatening severe asystole with a long pause. With respect to the cause of the unexpected cardiac event from the baseline clinical state, the potential risk of serious bradyarrhythmias was likely caused by the severe SAS, which was exacerbated by SAH, despite being low grade. Increased cardiac arrhythmias were observed until PBD 4 and decreased thereafter. After PBD 14, we observed no sinus arrest on 24-h ECG monitoring. Horie et al. reported that the inflammatory response peaked at 24−48 h after surgery for SAH,[

With respect to the influence of additional stress induced by surgery, the treatment should be as minimally invasive as possible. Horie et al. described a lower postoperative inflammatory response in patients receiving coiling compared with clipping, regardless of the WFNS grading of SAH. Thus, the selection of less invasive surgery, such as endovascular treatment, may help to decrease the arrhythmias associated with the catecholamine surge during the acute phase of SAH.[

CONCLUSION

We report a case of low-grade SAH with SAS, who experienced a life-threatening sinus arrest and required temporary pacemaker insertion. It is important to recognize the potential increased risk of bradyarrhythmia with the coexistence of these diseases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Becker HF, Koehler U, Stammnitz A, Peter JH. Heart block in patients with sleep apnoea. Thorax. 1998. 53: S29-32

2. Chen Z, Venkat P, Seyfried D, Chopp M, Yan T, Chen J. Brain-heart interaction: Cardiac complications after stroke. Circ Res. 2017. 121: 451-68

3. Chou TC, Susilavorn B. Electrocardiographic-pathological conference. electrocardiographic changes in intracranial hemorrhage. J Electrocardiol. 1969. 2: 193-6

4. Frangiskakis JM, Hravnak M, Crago EA, Tanabe M, Kip KE, Gorcsan J. Ventricular arrhythmia risk after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2009. 10: 287-94

5. Frontera JA, Parra A, Shimbo D, Fernandez A, Schmidt JM, Peter P. Cardiac arrhythmias after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Risk factors and impact on outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008. 26: 71-8

6. Fukui S, Katoh H, Tsuzuki N, Ishihara S, Otani N, Ooigawa H. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for QT prolongation following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care. 2003. 7: R7-12

7. Horie N, Iwaasa M, Isotani E, Ishizaka S, Inoue T, Nagata I. Impact of clipping versus coiling on postoperative hemodynamics and pulmonary edema after subarachnoid haemorrhage. Biomed Res Int. 2014. 2014: 807064-

8. Sakr YL, Lim N, Amaral AC, Ghosn I, Carvalho FB, Renard M. Relation of ECG changes to neurological outcome in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Int J Cardiol. 2004. 96: 369-73

9. van Jacob WA, van Bogaert A, De Groodt-Lasseel MH. Myocardial ultrastructure and haemodynamic reactions during experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1972. 4: 287-98

10. Vanninen E, Tuunainen A, Kansanen M, Uusitupa M, Länsimies E. Cardiac sympathovagal balance during sleep apnea episodes. Clin Physiol. 1996. 16: 209-16

11. Zwillich C, Devlin T, White D, Douglas N, Weil J, Martin R. Bradycardia during sleep apnea. Characteristics and mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1982. 69: 1286-92