- Department of Neuroimaging and Interventional Radiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_561_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Vivek Murumkar, Shumyla Jabeen, Sameer Peer, Aravinda Hanumanthapura Ramalingaiah, Jitender Saini. Ruptured vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm unmasking subclavian steal syndrome. 04-Dec-2020;11:419

How to cite this URL: Vivek Murumkar, Shumyla Jabeen, Sameer Peer, Aravinda Hanumanthapura Ramalingaiah, Jitender Saini. Ruptured vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm unmasking subclavian steal syndrome. 04-Dec-2020;11:419. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10426/

Abstract

Background: Subclavian steal occurs due to stenosis or occlusion of the subclavian artery or innominate artery proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery. Often asymptomatic, the condition may be unmasked due to symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency triggered by strenuous physical exercise involving the affected upper limb. The association of vertebrobasilar junction (VBJ) aneurysms with subclavian steal syndrome has been rarely reported. Hereby, we present a case of VBJ aneurysm associated with subclavian steal treated successfully with endovascular coiling.

Case Description: A 65-year-old female presented in the emergency department with acute severe headache and vomiting with no focal neurological deficits. Non-contrast computed tomography of the brain showed modified Fischer Grade 3 subarachnoid hemorrhage. Subsequent digital subtraction angiogram (DSA) showed VBJ aneurysm directed inferiorly with the left subclavian artery occlusion. There was retrograde filling of the left vertebral artery on right vertebral injection, confirming the diagnosis of subclavian steal. Balloon assisted coiling of the VBJ aneurysm was performed while gaining access through the stenotic left vertebral artery ostium which provided a more favorable hemodynamic stability to the coil mass.

Conclusion: Subclavian steal exerting undue hemodynamic stress on vertebrobasilar circulation can be an etiological factor for the development of the flow-related aneurysms. Access to the VBJ aneurysms may be feasible through the stenosed vertebral artery if angioplasty is performed before the coiling of the aneurysm.

Keywords: Aneurysm, Balloon, Coiling, Stenosis, Vertebral

INTRODUCTION

An intracranial aneurysm develops either due to an underlying defect in the tunica media of a blood vessel or excessive hemodynamic stress exerted on a normal blood vessel.[

CASE DESCRIPTION

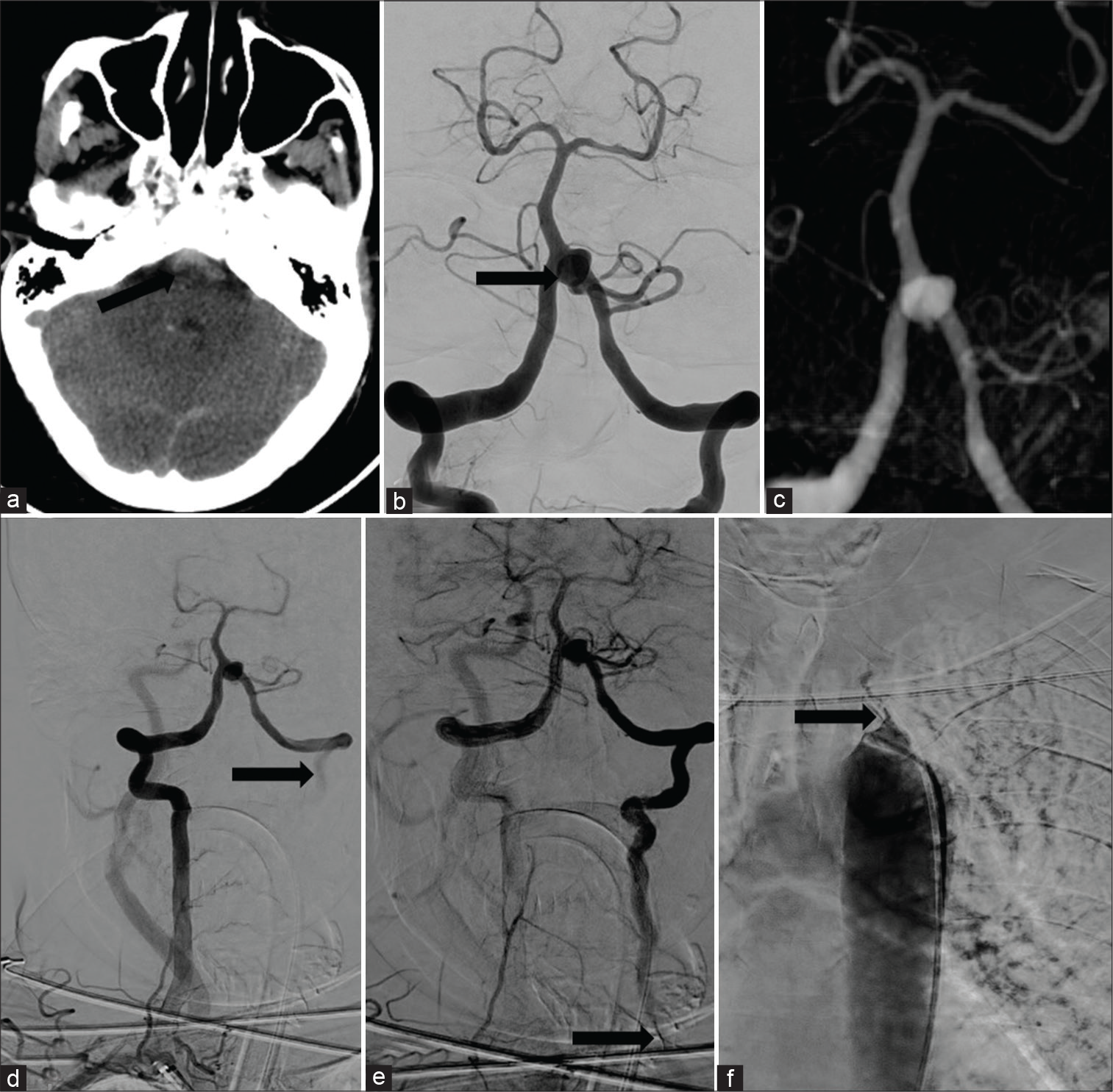

A 64-year-old female presented with a history of acute severe headache with vomiting. On examination, she was alert with no focal neurological deficits. Non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain showed modified Fisher Grade 3 subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the prepontine cistern [

Figure 1:

Axial CT brain showing modified Fischer grade 3 SAH in prepontine cistern (black arrow) (a). Right vertebral artery injection showing saccular aneurysm at vertebrobasilar (VB) junction (black arrow) with retrograde flow of contrast in left subclavian (b). 3D rotational angiogram showing saccular aneurysm arising from VB junction. (c) Long sheath injection from the right subclavian artery showing aneurysm in VB junction with retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery (black arrow) (d), next frame of previous run showing progressive retrograde filling of left vertebral artery till its origin from left subclavian artery (black arrow) (e). Aortogram showing tight stenosis of left subclavian origin (black arrow) (f).

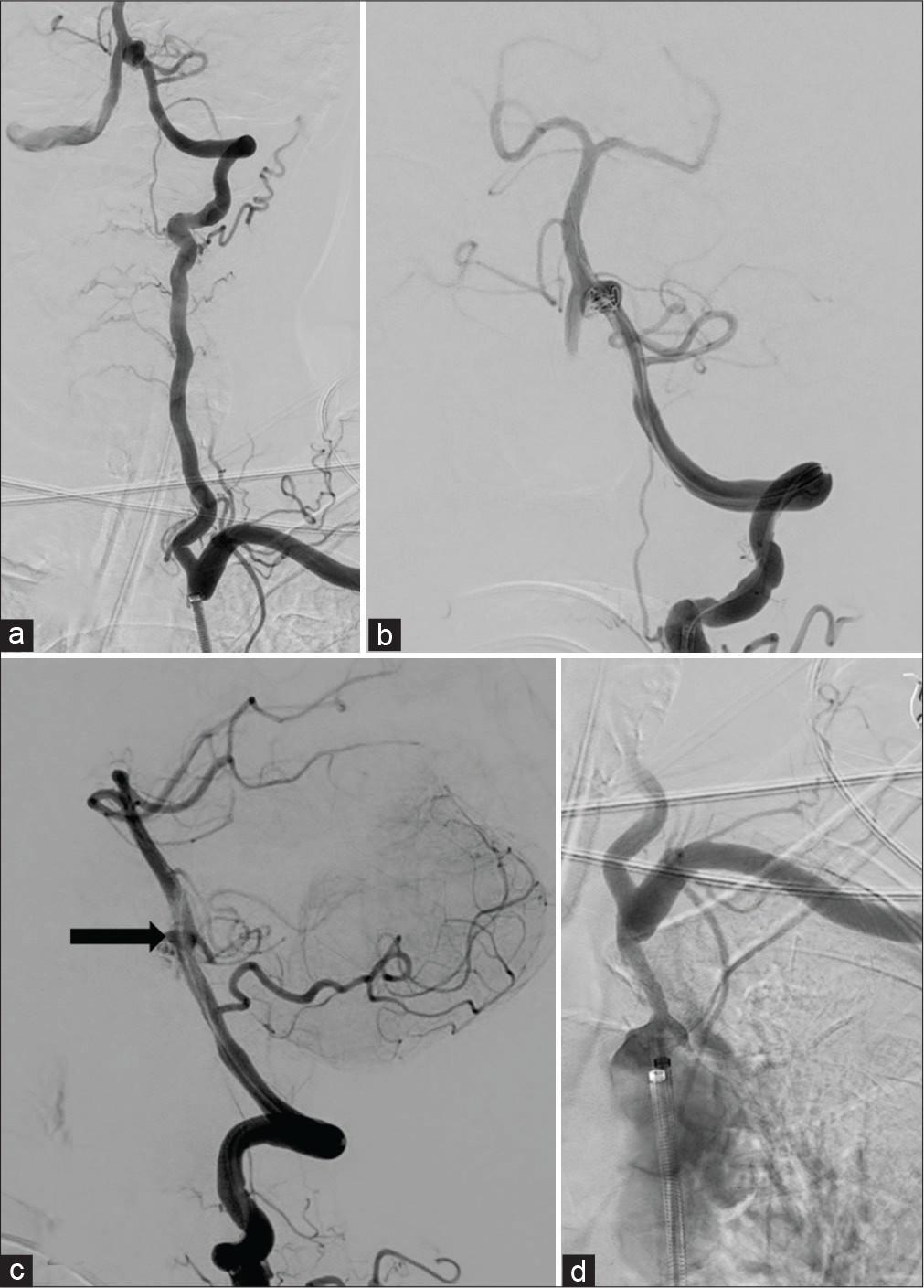

The procedure was done under general anesthesia. The right femoral artery was punctured with an 18G needle. Arterial access was secured with a 7F long sheath (Rabe Flexor, Cook) placed at the origin of right vertebral artery. 6F guiding catheter (Neuron, Penumbra Inc) was parked in the distal V2 segment of right vertebral artery. A balloon (Eclipse, Balt, France) was parked across the neck of the aneurysm and coiling attempted after cannulating the aneurysm sac with a microcatheter (Headway duo, Microvention, Tustin, CA, USA). However, the coil mass could not be retained inside the sac despite inflation of the balloon due to high flow across the VBJ. It was decided to take access from the left vertebral artery. The stenotic segment of the left subclavian artery was crossed with a 0.035” wire. A 5F vertebral catheter was negotiated across the stenosis over the wire and the 7F long sheath was subsequently tracked over it and placed at the origin of the left vertebral artery. The guiding catheter was parked in the V3 segment. Balloon assisted coiling was then successfully performed. Two coils were deployed into the aneurysm sac. Postcoiling angiogram showed Modified Raymond-Roy Class II occlusion of the aneurysm with normal filling of all vessels [

Figure 2:

Post angioplasty left subclavian injection showing anterograde flow in the left vertebral artery with filling of aneurysm (a). AP projection of the left vertebral injection after deployment of the first coil in the aneurysm sac (b). Lateral projection of the left vertebral injection after deployment of second coil showing minimal neck residue (black arrow) (c). Post coiling aortogram taken with long sheath in descending thoracic aorta showing residual stenosis at the left subclavian origin (d) note mild opening of the stenosis due to long sheath placement.

DISCUSSION

The phenomenon of “Subclavian steal” was first described by Reivich et al. in 1961 as a description of two cases and the demonstration of the hemodynamic phenomenon in four dogs.[

Intracranial aneurysms associated with SSS are very rare with only handful of cases reported in the literature so far.[

Definitive treatment of subclavian steal syndrome is by endoluminal balloon angioplasty with or without stenting or by carotid-subclavian bypass surgery and axillo-axillary bypass surgery.[

Thus, our case highlights a rare but important association between subclavian steal syndrome and intracranial flow-related aneurysm which can be an initial presenting feature. The exact cause of VBJ aneurysm development in cases of subclavian steal is not known; however, it has been postulated to be a result of hemodynamic stress due to increased flow across the VBJ in case of subclavian steal. This hypothesis is also supported by spontaneous regression of these aneurysms when the flow conditions across the VBJ are restored toward a low flow state. In their case description, Pasco et al. demonstrated spontaneous regression in the size of one flow related aneurysm of an intervertebral collateral in case of subclavian steal syndrome after surgical carotid-subclavian transposition.[

CONCLUSION

Subclavian steal syndrome is often asymptomatic and can rarely be unmasked by the rupture of intracranial flow-related aneurysm. VBJ is the most frequently reported site of this flow-related aneurysm. Endovascular approach is relatively safe for treating such aneurysms which can be performed by gaining vascular access either through the contralateral side or ipsilateral side by performing prior dilatation of the stenotic segment.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Ahuja CK, Joshi M, Mohindra S, Khandelwal N. Vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm associated with subclavian steal: Yet another hemodynamic cause for aneurysm development and associated challenges. Neurol India. 2020. 68: 708-9

2. Drake CG. The treatment of aneurysms of the posterior circulation. Clin Neurosurg. 1979. 26: 96-144

3. Gupta V, Ahuja CK, Khandelwal N, Kumar A, Gupta SK. Treatment of ruptured saccular aneurysms of the fenestrated vertebrobasilar junction with balloon remodeling technique. A short case series and review of the literature. Interv Neuroradiol. 2013. 19: 289-98

4. Okuhara T, Hashimoto K, Kanemaru K, Yoshioka H, Yagi T, Obata JE. A case of ruptured vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm associated with subclavian steal phenomenon. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017. 26: e160-4

5. Pasco A, Papon X, Fournier D, Mercier P, Caron-Poitreau C, Enon B. Subclavian steal syndrome and flow-related aneurysm, Another reason to treat. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1999. 40: 265-9

6. Peluso JP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Aneurysms of the vertebrobasilar junction: Incidence, clinical presentation, and outcome of endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007. 28: 1747-51

7. Potter BJ, Pinto DS. Subclavian steal syndrome. Circulation. 2014. 129: 2320-3

8. Psillas G, Kekes G, Constantinidis J, Triaridis S, Vital V. Subclavian steal syndrome: Neurotological manifestations. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2007. 27: 33-7

9. Reivich M, Holling HE, Roberts B, Toole JF. Reversal of blood flow through the vertebral artery and its effect on cerebral circulation. N Engl J Med. 1961. 265: 878-85

10. Schaarschmidt BM, Schlenkhoff CD, Heuser LJ. Two flow-related aneurysms of the circle of willis in an elderly patient with bilateral subclavian steal syndrome presenting as two different clinical manifestations. Rofo. 2013. 185: 482-4

11. Schatzl S, Karnik R, Gattermeier M. Coronary subclavian steal syndrome: An extracoronary cause of acute coronary syndrome. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013. 125: 437-8

12. Shakur SF, Alaraj A, Mendoza-Elias N, Osama M, Charbel FT. Hemodynamic characteristics associated with cerebral aneurysm formation in patients with carotid occlusion. J Neurosurg. 2019. 130: 917-22

13. Sheehy N, MacNally S, Smith CS, Boyle G, Madhavan P, Meaney JF. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography of subclavian steal syndrome: Value of the 2D time-of-flight “localizer” sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 185: 1069-73

14. Soldozy S, Norat P, Elsarrag M, Chatrath A, Costello JS, Sokolowski JD. The biophysical role of hemodynamics in the pathogenesis of cerebral aneurysm formation and rupture. Neurosurg Focus. 2019. 47: E11

15. Strozyk D, Mehta BP, Meyers PM, Nogueira RG. Coil embolization of intracranial dissecting vertebral artery aneurysms with subclavian steal. J Neuroimaging. 2011. 21: 62-4

16. Zaidat OO, Szeder V, Alexander MJ. Transbrachial stent-assisted coil embolization of right posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm: Technical case report. J Neuroimaging. 2007. 17: 344-7