- Department of Neurosurgery, Riverside University Health System, Moreno Valley, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of California, Riverside School of Medicine, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Kaiser Permanente, Fontana, California, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Tye Patchana

Department of Neurosurgery, Kaiser Permanente, Fontana, California, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_207_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Tye Patchana1, Hammad Ghanchi1, Taha Taka2, Mark Calayag3. Subgaleal hematoma evacuation in a pediatric patient: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 15-Aug-2020;11:243

How to cite this URL: Tye Patchana1, Hammad Ghanchi1, Taha Taka2, Mark Calayag3. Subgaleal hematoma evacuation in a pediatric patient: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 15-Aug-2020;11:243. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10214/

Abstract

Background: Subgaleal hematoma (SGH) is generally documented within the neonatal period and is rarely reported as a result of trauma or hair braiding in children. While rare, complications of SGH can result in ophthalmoplegia, proptosis, visual deficit, and corneal ulceration secondary to hematoma extension into the orbit. Although conservative treatment is preferential, expanding SGH should be aspirated to reduce complications associated with further expansion.

Case Description: A 12-year-old African-American female with no recent history of trauma presented with a chief complaint of headache along with a 2-day history of enlarging 2–3 cm ballotable bilateral frontal mass. Hematological workup was negative. The patient’s family confirmed a long history of hair braiding. The patient was initially prescribed a period of observation but returned 1-week later with enlarging SGH, necessitating surgical aspiration.

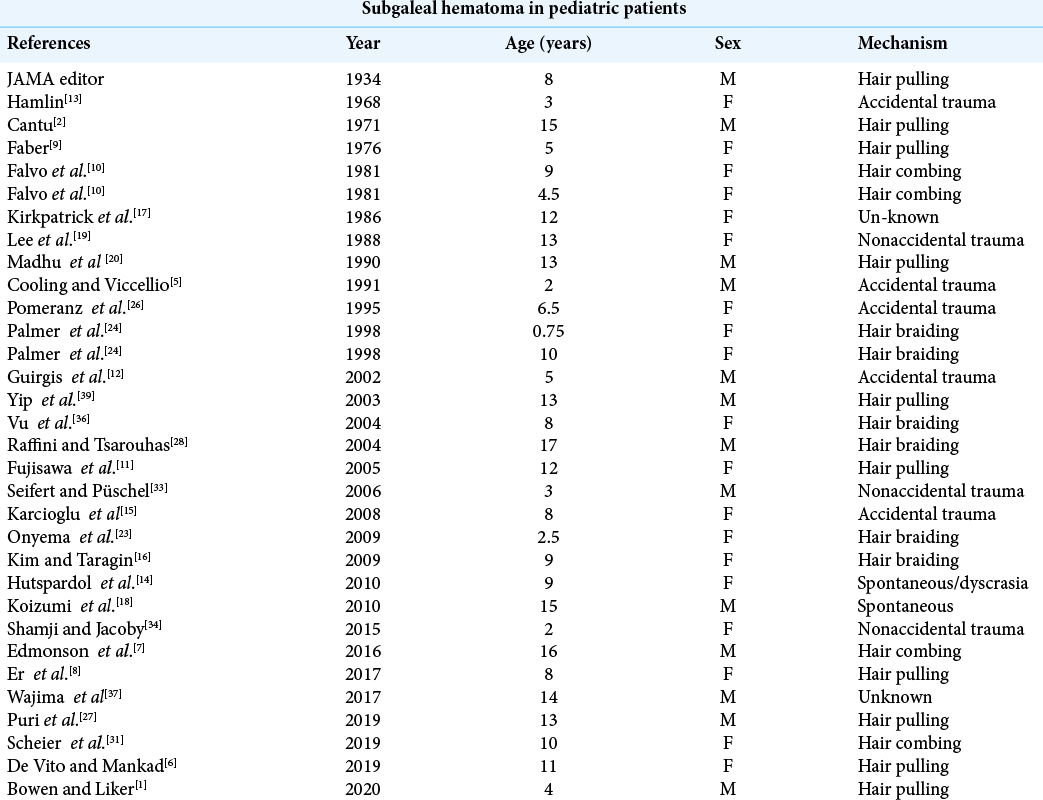

Conclusion: SGH is rare past the neonatal period, but can be found in pediatric and adolescent patients secondary to trauma or hair pulling. Standard workup includes evaluation of the patient’s hematological profile for bleeding or coagulation deficits, as well as evaluation for child abuse. Although most cases of SGH resolve spontaneously over the course of several weeks, close follow-up is recommended. The authors present a case of a 12-year-old female presenting with enlarging subgaleal hemorrhages who underwent surgical aspiration and drainage without recurrence. A literature review was also conducted with 32 pediatric cases identified, 20 of which were related to hair pulling, combing, or braiding. We review the clinical course, imaging characteristics, surgical management, as well as a review of the literature involving subgaleal hemorrhage in pediatric patients and hair pulling.

Keywords: Hair braiding, Subgaleal hematoma, Subgaleal hemorrhage

INTRODUCTION

First described in 1819 as a “false cephalohematoma, and later coined in 1957, subgaleal hematoma (SGH) is a collection of blood in the potential space between the periosteum and galeal aponeurosis, within loose areolar tissue.[

SGH is rare beyond the neonatal period and is typically associated with head trauma resulting in rupture of emissary veins traversing the subgaleal space.[

Recognition of the clinical manifestations and presentation is important for appropriate management. As advocated by other authors,[

CASE DESCRIPTION

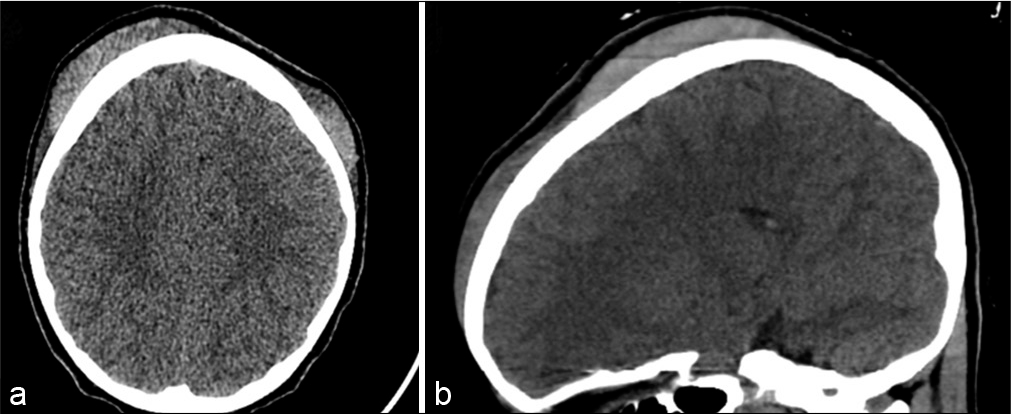

Our patient was a 12-year-old African-American female presenting with a chief complaint of headache, as well as a 2-day history of enlarging 2–3 cm ballotable bilateral frontal mass. The patient and her family denied any antecedent incidence of trauma, as well as any patient or family history of blood dyscrasias. The patient had an uncomplicated birth history, delivered vaginally at term, with no significant medical history or medication usage. Her family endorsed a long history of hair braiding since the patient was a toddler. With the exception of ballotable mass encompassing the bilateral forehead, the patient’s examination was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) of the head [

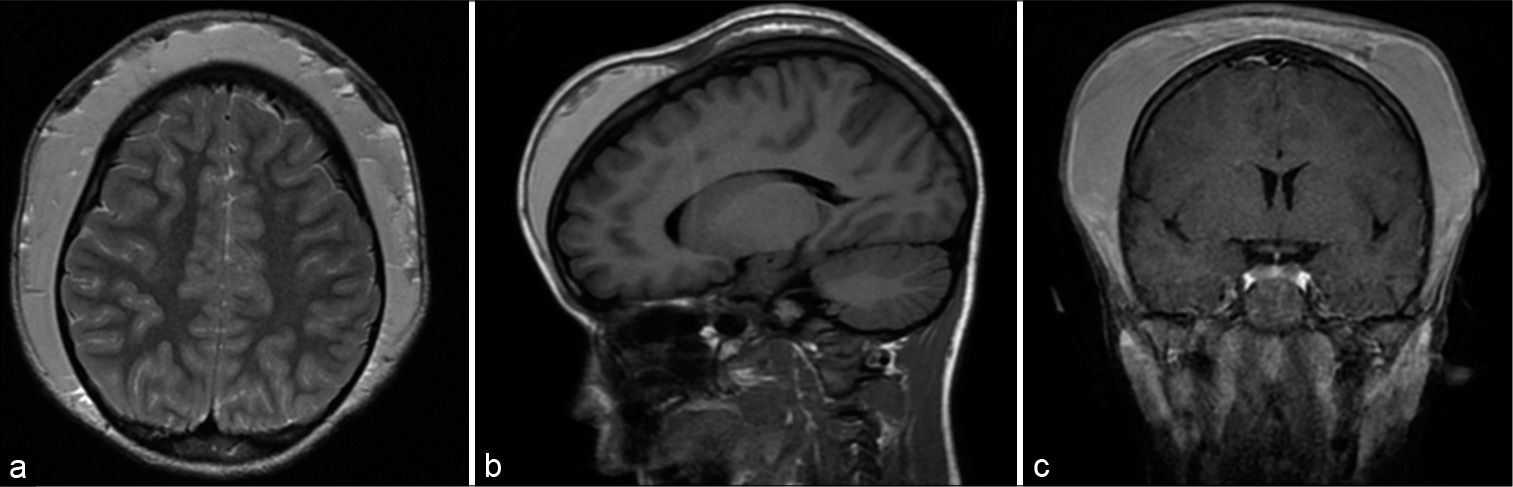

Laboratory results demonstrated normal platelet aggregation, Von Willebrand, and Factor 8 and Factor 13 testing. The patient presented without fever, and the rest of her vital signs were unremarkable. The patient was subsequently discharged with follow-up with a pediatric neurosurgery clinic in 2 weeks. One week later, the patient returned with an enlarging subgaleal fluid collection. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without intravenous gadolinium was performed, demonstrating an interval increase in bilateral frontal and parietal scalp hematoma to 2.3 cm, compared to prior noncontrast CT of the head [

Figure 2:

(a) Axial T2 MRI brain demonstrating bilateral subgaleal fluid collections, enlarged compared to noncontrast CT had a week prior, (b) sagittal T1 flair brain demonstrating collections along the frontal and parietal aspects of the calvarium, and (c) coronal noncontrast T1 MRI of the brain demonstrating bilateral subgaleal hematoma formation.

Although most cases of SGH resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, and therefore, the risk of infections secondary to aspiration and drainage is usually deferred, our patient returned with a worsening clinical course. Therefore, the risks, benefits, and alternatives to bedside drainage were explained to the patient’s family, who decided to proceed.

Given increasing size and overall worsening clinical course of the SGH, the intervention was prompted. A 24 gauge butterfly needle connected to the syringe was inserted into the epidermis in a Z-shaped fashion and slowly advanced with negative pressure at the center of the forehead behind the hairline until a flash of fluid was noted. Only one insertion of the needle was required. Approximately 300 mL of dark, motor oil-like fluid [

DISCUSSION

SGH results from the collection of blood between the aponeurosis and the periosteum of the skull. The mechanism likely involves accumulation of blood in the subgaleal layer, where emissary veins drain superficial scalp veins to the dural sinuses.[

A literature review was conducted utilizing Google Scholar and PubMed. Both neonatal (birth up to 4 weeks) and adult cases were excluded from the search. The most comprehensive literature review to date was performed by Scheier et al. and included 16 pediatric cases involving hair pulling or straightening.[

CONCLUSION

SGH is rare past the neonatal period but can be found in pediatric and adolescent patients. Standard workup includes evaluation of the patient’s hematological profile for bleeding or coagulation deficits, as well as evaluation for child abuse. Although most cases of subgaleal hemorrhage resolve spontaneously over the course of several weeks,[

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Bowens JP, Liker K. Subgaleal hemorrhage secondary to child physical abuse in a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020. p.

2. Cantu RC. Complication of long hair. Lancet. 1971. 1: 350

3. Chen CE, Liao ZZ, Lee YH, Liu CC, Tang CK, Chen YR. Subgaleal hematoma at the contralateral side of scalp trauma in an adult. J Emerg Med. 2017. 53: e85-8

4. Chen SH, Soong WJ, Hsieh YL, Chen SJ, Hwang B. Hemophilia A presenting with intracranial hemorrhage in neonate: A case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1994. 54: 62-6

5. Cooling DS, Viccellio P. Massive subgaleal hematoma following minor head trauma. J Emerg Med. 1991. 9: 33-5

6. De Vito A, Mankad K. Our experience of subgaleal haematoma due to hair pulling. Acta Paediatr. 2020. 109: 426

7. Edmondson SJ, Ramman S, Hachach-Haram N, Bisarya K, Fu B, Ong J. Hair today; scalped tomorrow: Massive subgaleal haematoma following sudden hair pulling in an adolescent in the absence of haematological abnormality or skull fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 2016. 27: 1261-2

8. Er A, Çağlar A, Akgül F, Ulusoy E, Karsli E, Yilmaz D. A rare cause of subgaleal hematoma in children: Hair pulling. J Pediatr Emerg Intensive Care Med. 2017. 4: 33-5

9. Faber MM. Massive subgaleal hemorrhage: A hazard of playground swings. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1976. 15: 384-5

10. Falvo CE, San Filippo JA, Vartany A, Osborn EH. Subgaleal hematoma from hair combing. Pediatrics. 1981. 68: 583-4

11. Fujisawa H, Yonaha H, Oka Y, Uehara M, Nagata Y, Kajiwara K. A marked exophthalmos and corneal ulceration caused by delayed massive expansion of a subgaleal hematoma. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005. 21: 489-92

12. Guirgis MF, Segal WA, Lueder GT. Subperiosteal orbital hemorrhage as initial manifestation of Christmas disease (factor IX deficiency). Am J Ophthalmol. 2002. 133: 584-5

13. Hamlin H. Subgaleal hematoma caused by hair-pull. JAMA. 1968. 204: 339

14. Hutspardol S, Chuansamrit A, Soisamrong A. Spontaneous subgaleal hemorrhage in a girl with impaired adrenaline-induced platelet aggregation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2010. 93: 625-8

15. Karcioglu ZA, Hoehn ME, Lin YP, Walsh J. Ocular involvement after subgaleal hematoma. J AAPOS. 2008. 12: 521-3

16. Kim D, Taragin B. Subgaleal hematoma presenting as a manifestation of factor XIII deficiency. Pediatr Radiol. 2009. 39: 622-4

17. Kirkpatrick JS, Gower DJ, Chauvenet A, Kelly DL. Subgaleal hematoma in a child, without skull fracture. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1986. 28: 511-4

18. Koizumi K, Suzuki S, Utsuki S, Nakahara K, Niki J, Mabuchi I. A case of non-traumatic subgaleal hematoma effectively treated with endovascular surgery. Interv Neuroradiol. 2010. 16: 317-21

19. Lee KS, Bae HG, Yun IG. Bilateral proptosis from a subgaleal hematoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1988. 69: 770-1

20. Madhu SV, Agarwal S. Subgaleal haematoma following hair pulling. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990. 38: 955

21. Nichter LS, Bolton LL, Reinisch JF, Sloan GM. Massive subgaleal hematoma resulting in skin compromise and airway obstruction. J Trauma. 1988. 28: 1681-3

22. Okafor BC. Bilateral otorrhagia and orbital hematoma complicating subgaleal hematoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984. 93: 237-9

23. Onyeama CO, Lotke M, Edelstein B. Subgaleal hematoma secondary to hair braiding in a 31-month-old child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009. 25: 40-1

24. Palmer KM, Olan WJ, Vezina LG, Dubovsky EC. Scalp hematomas in children after hair braiding. Emerg Radiol. 1998. 5: 176-9

25. Plauché WC. Subgaleal hematoma. A complication of instrumental delivery. JAMA. 1980. 244: 1597-8

26. Pomeranz AJ, Ruttum MS, Harris GJ. Subgaleal hematoma with delayed proptosis and corneal ulceration. Ann Emerg Med. 1995. 26: 752-4

27. Puri S, Duff SM, Mueller B, Prendes M, Clark J. Hairpulling causing vision loss: A case report. Orbit. 2019. 38: 162-5

28. Raffini L, Tsarouhas N. Subgaleal hematoma from hair braiding leads to the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004. 20: 316-8

29. Rohyans JA, Miser AW, Miser JS. Subgaleal hemorrhage in infants with hemophilia: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1982. 70: 306-7

30. Ryan CA, Gayle M. Vitamin K deficiency, intracranial hemorrhage, and a subgaleal hematoma: A fatal combination. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1992. 8: 143-5

31. Scheier E, Ben-Ami T, Guri A, Balla U. Subgaleal hematoma from a carnival costume. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019. 21: 422-3

32. Scheier E, Guri A, Balla U. Subgaleal haematoma due to hair pulling: Review of the literature. Acta Paediatr. 2019. 108: 2170-4

33. Seifert D, Püschel K. Subgaleal hematoma in child abuse. Forensic Sci Int. 2006. 157: 131-3

34. Shamji S, Jacoby JL. Massive subgaleal hematoma and clinical suspicion of child abuse. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015. 115: 58-60

35. Vacca A. Risk factors associated with subaponeurotic haemorrhage in full-term infants exposed to vacuum extraction. BJOG. 2006. 113: 491

36. Vu TT, Guerrera MF, Hamburger EK, Klein BL. Subgaleal hematoma from hair braiding: Case report and literature review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004. 20: 821-3

37. Wajima D, Nakagawa I, Kotani Y, Wada T, Yokota H, Park YS. A case of refractory subgaleal hematoma in adolescence treated with aspiration and endovascular surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2017. 159: 1565-9

38. Wolter JR, Vanderveen GJ, Wacksman RL. Posttraumatic subgaleal hematoma extending into the orbit as a cause of permanent blindness. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1978. 15: 151-3

39. Yip CC, McCulley TJ, Kersten RC, Kulwin DR. Proptosis after hair pulling. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 19: 154-5

Alireza Taghikhani MD

Posted September 12, 2020, 8:29 am

I read your paper with enthusiasm and interest, since I had some patient with the same problem. Chronic subg-aleal collection as my definition is the one that not resolved after four weeks or increased in size without any recent trauma. As you mentioned child abuse should be considered in this condition. One of my plans for this patient beside elastic bandage is put a vacuum drain for 48 to 72 hours and keep elastic bandage for few days more. It was effective in almost all the cases. As we know risk of infection should be considered in these cases before invasive procedure and prophylactic antibiotics can be considered.