- Department of Neurosurgery, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

- Department of Neurology, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

Correspondence Address:

Merdin L. Ahmedov

Department of Neurosurgery, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_99_18

Copyright: © 2018 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Merdin L. Ahmedov, Taha S. Korkmaz, Rahsan Kemerdere, Seher N. Yeni, Taner Tanriverdi. Surgical and neurological complications in temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in modern era. 13-Jul-2018;9:134

How to cite this URL: Merdin L. Ahmedov, Taha S. Korkmaz, Rahsan Kemerdere, Seher N. Yeni, Taner Tanriverdi. Surgical and neurological complications in temporal lobe epilepsy surgery in modern era. 13-Jul-2018;9:134. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/surgical-and-neurological-complications-in-temporal-lobe-epilepsy-surgery-in-modern-era/

Abstract

Background:Temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common form of focal epilepsy, and surgical treatment has been proven to be an effective and safe management. Despite its safety, it is important to know that some complications and/or even death can be seen after surgery. Neurosurgeons should be able to precisely inform epilepsy surgery candidates about the possible unwanted/unexpected conditions after surgery.

Methods:Fifty-three patients who underwent anterior temporal lobe resection due to temporal lobe epilepsy by a single surgeon were investigated retrospectively regarding postoperative surgical and neurological complications.

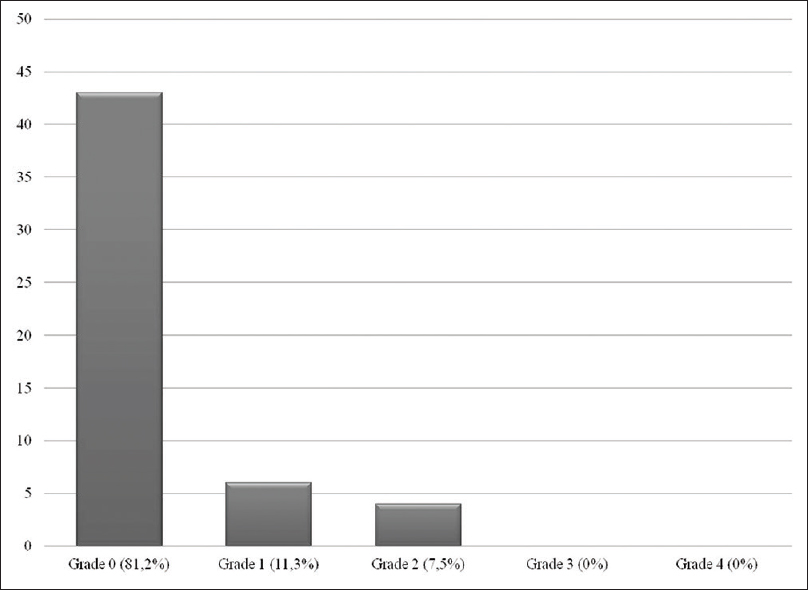

Results:Overall complication rate was found to be 19%, surgical complications comprised 13.2% whereas neurological complications were 5.8%. Three patients underwent a second surgery whereas the rest had medical treatment or recovered spontaneously. Fortunately persistent complication rate was found to be 0%, and there was no mortality.

Conclusions:Anterior temporal lobe resection is a safe and very effective surgical modality for the treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy. However, unexpected complications may be possible in this modern era and a surgeon should trust in him/herself not in modern equipments.

Keywords: Surgical complication, epilepsy, surgery, temporal lobe

INTRODUCTION

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the most common form of focal epilepsy, and surgical treatment has been proven to be an effective and safe management.[

In the literature, there have been several reports mentioning the complications of epilepsy surgery including the ones performed in different epilepsy disorders,[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively analyzed the complications seen after 53 CAH procedures done by the senior author (TT) between November 2009 and January 2017 in TLE patients older than 18 years of age who were followed up for at least 12 months. A multidisciplinary team evaluated standardized presurgical data consisting of neurological, neuropsychological and psychiatric examinations, ictal and interictal scalp video electroencephalograms (EEG), brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), interictal positron emission tomography (PET), and invasive EEG [stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG)], if needed. Patients who were thought to benefit from surgery were offered to have CAH. We reviewed all the included patients’ files and postoperative brain MRIs. The parameters included age at surgery, gender, side of operation, use of SEEG, and surgical and neurological complications.

Classification of complications

Although there is no universal definition of complication after TLE surgery, complication is defined in the literature as an unwanted, unexpected, and uncommon event after a surgical procedure.[

Statistical analysis

We used a commercially available statistical software package (SPSS version 22.0 Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for all statistical analyses. The mean ± SD was calculated for appropriate parameters.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

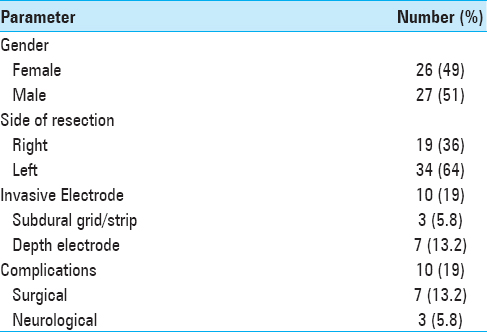

This analysis was based on 53 patients with drug-resistant TLE who underwent CAH (ATL). Their mean age at surgery was 30.4 ± 9.0 (range, 19–55 years) and the male/female ratio was 1.04. Thirty-four patients (64%) were operated on the left side and 19 (36%) on the right side. Ten patients (18.8%) underwent SEEG, 7 of which had depth electrodes, while 3 underwent subdural grid/strip [

Overall complications

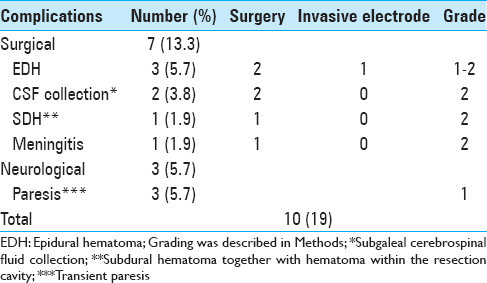

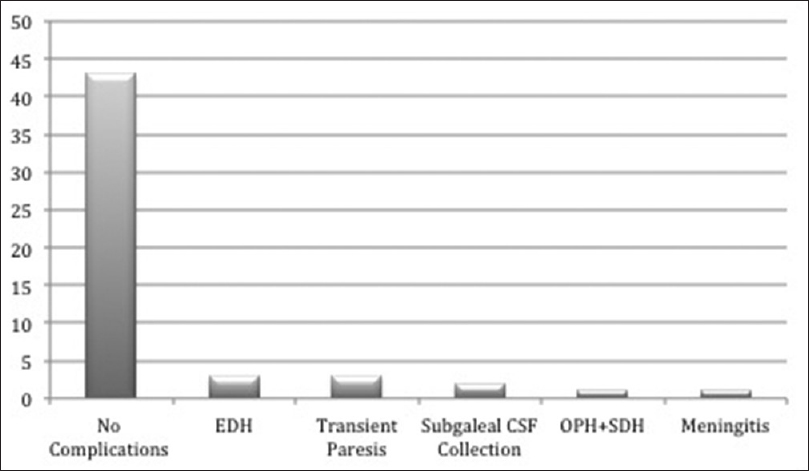

Recovery from surgery was uneventful in 43 patients (81%). The complications of 10 patients are summarized in

Surgical complications

Seven (13.2%) of the 10 complications were directly related to surgery. They consisted of 3 epidural hematomas (EDH), 1 hematoma within the resection cavity together with subdural hematoma (SDH), 2 subgaleal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collections, and 1 meningitis. The one with hematoma within the resection cavity and 1 of the 3 EDHs were surgically evacuated immediately after the first surgery. One EDH was only clinically observed without a need for surgical intervention, whereas the last one was diagnosed 1 week after discharge. There were no depth electrode or subdural grid-related complications.

The patient with delayed EDH was a 27-year-old man. He was admitted with fever and headache 1 week after discharge. Cranial MRI was performed and a contrast-enhancing epidural collection was seen. The contrast enhancement was thought to be related to epidural empyema. Fortunately, no obvious pus was observed during surgery, and there was no sign of infection that was proven by microbiological cultures. The postoperative period was uneventful and he was discharged without any neurological deficit.

The one with hematoma within the resection cavity together with SDH was a 41-year-old male who had sudden worsening in neurological status (Glasgow coma scale: 9/15) 6 hours after the surgery. The patient was urgently taken to the operating room following CT scan, and the hematoma was evacuated successfully. He recovered completely 24 hours after the second surgery and was discharged from the hospital without neurological sequelae.

Two patients with subgaleal CSF collections did not have leakage through the skin and collections were withdrawn percutaneously without surgical intervention.

A 42-year-old male was readmitted to our clinic with fever, nuchal stiffness, and vomiting 1 week after discharge, and 10 days of treatment with appropriate intravenous (IV) antibiotics was sufficient to cure the infection. All the surgical complications recovered without any persistent sequelae.

Neurological complications

Three patients (5.6%) showed neurological complications. Two patients had transient hemiparesis and 1 had only mild transient paresis of her foot. Diffusion tension MRI sequences of both patients with hemiparesis showed diffusion restriction on the posterior limbs of internal capsules ipsilateral to the lesions, whereas there was a middle cerebral artery territory infarction in the patient with monoparesis. Overall, they typically showed marked recovery within the first 48 hours postoperatively. Transient hemiparesis seems to be related to anterior choroidal artery vasospasm due to surgical manipulation which was reported before.[

DISCUSSION

As it is well described that epilepsy surgery for TLE is very effective in seizure control, greatly increasing long-term quality of life and lowering medication use,[

Tanriverdi et al.[

Our results concerning the complication rates are in line with the previous series revealing that surgery for TLE is a safe treatment. However, unexpected complications such as vasospasm due to manipulation, as seen in one of our cases, or direct surgical injury to anterior choroidal artery during uncus and amygdala resection can occur. Despite the availability of modern surgical equipment, serious complications are still possible and patients should be informed about such complications by the epilepsy team before surgery.

Limitations

This report has some limitations. First, this is a retrospective data analysis which can cause bias. Second, limited number of patients were included. This report did not provide information about neuropsychological and seizure outcomes as the aim of this short report was to focus on complications directly related to surgery. We did not evaluate the postoperative visual field deficits of patients since it is reported as an expected finding in ATL.[

CONCLUSION

The results of this short report underlines that, although surgery for TLE can be safe when performed by experienced surgeons, unexpected complications are still possible. Thus, these risks should be explained to patients before surgery. More importantly, neurosurgeons should not trust in modern equipment entirely during surgery, instead the only thing that an epilepsy surgeon should trust must be him/herself.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Georgiadis I, Kapsalaki EZ, Fountas KN. Temporal lobe resective surgery for medically intractable epilepsy: A review of complications and side effects. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2013. 2013: 752195-

2. Gooneratne IK, Mannan S, de Tisi J, Gonzalez JC, McEvoy AW, Miserocchi A. Somatic complications of epilepsy surgery over 25 years at a single center. Epilepsy Res. 2017. 132: 70-7

3. Helgason C, Caplan LR, Goodwin J, Hedges T. Anterior choroidal artery-territory infarction. Report of cases and review. Arch Neurol. 1986. 43: 681-6

4. Lee JH, Hwang YS, Shin JJ, Kim TH, Shin HS, Park SK. Surgical complications of epilepsy surgery procedures: Experience of 179 procedures in a single institute. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2008. 44: 234-9

5. Mathon B, Navarro V, Bielle F, Nguyen-Michel VH, Carpentier A, Baulac M. Complications after surgery for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy associated with hippocampal sclerosis. World Neurosurg. 2017. 102: 639-50

6. Olivier A, Boling WW, Tanriverdi T.editors. Techniques in epilepsy surgery: The MNI approach. UK: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p.

7. Tanriverdi T, Ajlan A, Poulin N, Olivier A. Morbidity in epilepsy surgery: An experience based on 2449 epilepsy surgery procedures from a single institution. J Neurosurg. 2009. 110: 1111-23

8. Tanriverdi T, Olivier A, Poulin N, Andermann F, Dubeau F. Long-term seizure outcome after mesial temporal lobe epilepsy surgery: Corticalamygdalohippocampectomy versus selective amygdalohippocampectomy. J Neurosurg. 2008. 108: 517-24

9. Tanriverdi T, Poulin N, Olivier A. Life 12 years after temporal lobe epilepsy surgery: A long-term, prospective clinical study, Seizure. 2008. 17: 339-49

10. Vale FL, Reintjes S, Garcia HG. Complications after mesial temporal lobe surgery via inferior temporal gyrus approach. Neurosurg Focus. 2013. 34: E2-

11. Wellmer J, von der Groeben F, Klarmann U, Weber C, Elger CE, Urbach H. Risks and benefits of invasive epilepsy surgery workup with implanted subdural and depth electrodes. Epilepsia. 2012. 53: 1322-32