- Departments of Neurosurgery, Università Politecnica delle Marche , Ancona, Marche, Italy.

- Departments of Neurology, Università Politecnica delle Marche , Ancona, Marche, Italy.

Correspondence Address:

Dobran Mauro

Departments of Neurosurgery, Università Politecnica delle Marche , Ancona, Marche, Italy.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_583_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Dobran Mauro, Davide Nasi, Riccardo Paracino, Mara Capece, Erika Carrassi, Denis Aiudi, Fabrizio Mancini, Simona Lattanzi, Roberto Colasanti, Maurizio Iacoangeli. The relationship between preoperative predictive factors for clinical outcome in patients operated for lumbar spinal stenosis by decompressive laminectomy. 25-Feb-2020;11:27

How to cite this URL: Dobran Mauro, Davide Nasi, Riccardo Paracino, Mara Capece, Erika Carrassi, Denis Aiudi, Fabrizio Mancini, Simona Lattanzi, Roberto Colasanti, Maurizio Iacoangeli. The relationship between preoperative predictive factors for clinical outcome in patients operated for lumbar spinal stenosis by decompressive laminectomy. 25-Feb-2020;11:27. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9877/

Abstract

Background:Our hypothesis was that by identifying certain preoperative predictive factors, we could favorably impact clinical outcomes in patients undergoing decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS).

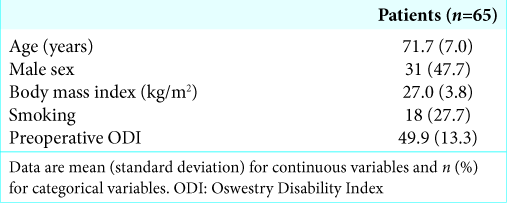

Methods:In this retrospective study, there were 65 patients (2016–2018) with symptomatic LSS who underwent decompressive laminectomy without fusion. Their clinical outcomes were assessed utilizing the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Multiple preoperative variables were studied to determine which ones would help predict improved outcomes: gender, age, body mass index (BMI), general/neurological examination, smoking, and drug therapies (anxiolytics and/or antidepressants).

Results:All patients demonstrated statistically significant improvement on the ODI. Multivariate analysis revealed that those with higher preoperative BMI had significantly lower ODI on 1-year follow-up examinations, reflecting poorer outcomes. Postoperatively, 44 patients (67%) exhibited lower utilization of anxiolytic medications, 52 patients (80%) showed reduced use of antidepressant drugs, and pain medications utilization was reduced in 33 patients (50%).

Conclusion:Decompressive laminectomy without fusion effectively managed LSS. It reduced patients’ use of pain, anxiety, and antidepressant medications. In addition, we found that increased preoperative BMIs contributed to poorer postoperative outcomes (e.g., ODI values).

Keywords: Body mass index, Decompressive laminectomy, Lumbar spinal stenosis, Obesity in spine surgery, Oswestry Disability Index scale

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) can be effectively treated with decompressive laminectomy without fusion. Here, we asked what preoperative risk factors would contribute to poorer postoperative outcomes. Notably, the literature had previously shown that elevated preoperative body mass index (BMI) and a history of smoking both contributed to poorer outcomes following decompressive LSS surgery.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study included 65 patients averaging 70.4 years of age with LSS undergoing decompressive laminectomy without fusion. There were 36 males (56%) and 29 females (44%). All patients failed conservative treatment for at least 6 months before undergoing LSS surgery. Those with a diagnosis of spondylolisthesis, spinal tumors, infections, or prior surgery were excluded from this analysis. The following preoperative parameters were assessed to determine their impact on surgical outcomes: gender, age, BMI, smoking history, use of pain/antidepressant/anxiolytic medications, and preoperative neurological deficit/disability level. The latter was estimated utilizing the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score, evaluated preoperatively and 1, 6, and 12 months postoperatively (follow-up) [

Statistical analysis

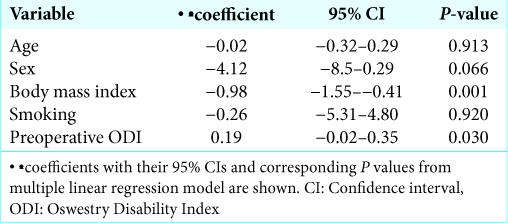

Values were presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as the number (percentage) of subjects for categorical variables. The outcome measure was the change in disability estimated as the difference between the ODI values obtained at 12 and 1 month after surgery. The associations between the disability change and baseline variables were assessed using a linear regression model and included the analysis of age, sex, BMI, smoking status, and preoperative ODI. Results were considered significant for P < 0.05 (two sided). Data analysis was performed using STATA/IC 13.1 statistical package (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

There was a statistically significant improvement in ODI values for all patients. The multivariate analysis revealed that patients with high preoperative BMI had significantly lesser postoperative ODI at 1 postoperative year (e.g., poor outcomes). After surgery, 44 patients (67%) reduced the use of anxiolytic drugs, 52 patients (80%) used fewer antidepressants, and 33 patients (50%) took fewer pain medications. Other factors such as age and gender were not statistically significant [

DISCUSSION

Some authors showed equivalent clinical outcomes for those with elevated preoperative BMI and a history of smoking; alternatively, they attributed poorer postoperative results to increased perioperative blood loss and more chronic preoperative lumbar pain contributing to longer hospital length of stay.[

Other literature documented that both obesity and smoking contributed to greater perioperative risks/complications of laminectomy for LSS.[

CONCLUSION

Decompressive laminectomy to treat lumbar spinal stenosis was effective to treat pain and disability. In this prospective study baseline elevated BMI was statistically associated with postoperative poor results in terms of ODI value.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. De la Garza-Ramos R, Bydon M, Abt NB, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky JP, Bydon A. The impact of obesity on short-and long-term outcomes after lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015. 40: 56-61

2. Dobran M, Mancini F, Nasi D, Scerrati M. A case of deep infection after instrumentation in dorsal spinal surgery: The management with antibiotics and negative wound pressure without removal of fixation. BMJ Case Rep. 2017. 2017: bcr-2017-220792

3. Dobran M, Nasi D, Paracino R, Gladi M, Costanza MD, Marini A. Analysis of risk factors and postoperative predictors for recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Surg Neurol Int. 2019. 10: 36-

4. Garcia RM, Messerschmitt PJ, Furey CG, Bohlman HH, Cassinelli EH. Weight loss in overweight and obese patients following successful lumbar decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008. 90: 742-7

5. Giannadakis C, Nerland US, Solheim O, Jakola AS, Gulati M, Weber C. Does obesity affect outcomes after decompressive surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis? A multicenter, observational, registry-based study. World Neurosurg. 2015. 84: 1227-34

6. Knutsson B, Mukka S, Wahlström J, Järvholm B, Sayed-Noor AS. The association between tobacco smoking and surgical intervention for lumbar spinal stenosis: Cohort study of 331, 941 workers. Spine J. 2018. 18: 1313-7

7. Knutsson B, Sandén B, Sjödén G, Järvholm B, Michaëlsson K. Body mass index and risk for clinical lumbar spinal stenosis: A cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015. 40: 1451-6

8. Maugeri R, Graziano F, Giugno A, Iacopino DG. A new concept to treat lumbar spine stenosis in a mini invasive way. J Neurosurg Sci. 2017. 61: 347-8

9. Onyekwelu I, Glassman SD, Asher AL, Shaffrey CI, Mummaneni PV, Carreon LY. Impact of obesity on complications and outcomes: A comparison of fusion and nonfusion lumbar spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017. 26: 158-62

10. Sielatycki JA, Chotai S, Stonko D, Wick J, Kay H, McGirt MJ. Is obesity associated with worse patient-reported outcomes following lumbar surgery for degenerative conditions?. Eur Spine J. 2016. 25: 1627-33

11. Vazquez-Anguilar A, Gomez AT, AtlitecCastillo PT, De leon Martinez JE. Espondilolistesis degenerative. Influencia del indice de masa corporal en la evolucion postquirurgica.. Acta Ortop Mex. 2016. 30: 13-160