- Department of Neurosurgery, Neuroscience Institute, Allegheny General Hospital, Drexel University College of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Medicine, Helwan University, Cairo, Egypt.

Correspondence Address:

Mohamed Elnokaly

Department of Neurosurgery, Neuroscience Institute, Allegheny General Hospital, Drexel University College of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States,

DOI:10.25259/SNI_200_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Mohamed Elnokaly, Gordon Mao, Khaled A. Aziz. The transpalpebral approach “eyelid incision” for surgical management of intracranial tumors: A 10-years’ experience. 11-Jul-2020;11:186

How to cite this URL: Mohamed Elnokaly, Gordon Mao, Khaled A. Aziz. The transpalpebral approach “eyelid incision” for surgical management of intracranial tumors: A 10-years’ experience. 11-Jul-2020;11:186. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10128/

Abstract

Background: The minimally invasive approaches to the anterior skull base region through fronto-orbital craniotomy remain a highly accepted option that gains countenance and predilection over time. The transpalpebral “eyelid” incision is an under-utilized and more recent technique that offers a safe efficient corridor to manage a wide variety of lesions.

Methods: We carried a retrospective study of 44 patients operated on by the fronto-orbital craniotomy through transpalpebral “eyelid” incision for intracranial tumors, in the time period from March 2007 to July 2016. The results from surgeries were analyzed; extent of tumor resection, length of hospital stay, cosmetic outcome, and complications.

Results: Out of the 44 intracranial tumor cases, we had 16 male and 28 female patients with median age 54 years. We had 19 anterior skull base lesions, 8 middle skull base lesions and 8 parasellar lesions. We also operated on four frontal intraparenchymal lesions and four other various lesions. Total resection was achieved in 32 cases (72.7%), with excellent cosmetic outcome in 43 cases (97.7%). Average hospital stay was 6 days. No major complications recorded. Three cases (6.8%) had complications that varied between pseudomeningocele, wound infections, and facial pain. Follow-up average period was 23.6 months.

Conclusion: The fronto-orbital approach through eyelid incision remains a reliable approach to the skull base. It provides natural anatomical dissection planes through the eyelid incision and a fronto-orbital craniotomy, creating a wide surgical corridor to manage specific lesions with consistent surgical and cosmetic outcome.

Keywords: Eyelid, Minimally invasive, Skull base, Transpalpebral, Tumors

INTRODUCTION

Recent advancements of stereotactic image guidance and endoscopic surgery over the past 3–4 decades have paved the way for the minimally invasive skull base surgery to invade neurosurgical concepts. These concepts were supported by fruitful results coming from initial experiences of utilizing minimally invasive supraorbital craniotomy in managing challenging skull base lesions.[8,14,17,18] These developments have prompted other neurosurgeons to adopt and innovate other minimal invasive approaches for skull base pathologies.

The lesions that formerly required large skin incisions, wide craniotomies, and significant brain retraction are now managed through minicraniotomies, through a hidden eyebrow versus eyelid incisions, offering a wide surgical corridor. While the suprafrontal craniotomy through an eyebrow incision has been well described as a safe and versatile approach across multiple large retrospective series in the past two decades, the supraorbital frontal craniotomy through the eyelid incision remains a relatively unknown approach with very limited literature documenting the nuances of this approach.

The supraorbital frontal craniotomy with and without an orbitotomy through an eyelid has evolved to become a versatile approach that could ease the management of most types of anterior and some middle fossa lesions. The approach was initially accessed through eyebrow incision reported excellent outcomes.[4,5,7,8,14,16-19,21,24] Minifrontal or fronto-orbital craniotomy can almost achieve the same surgical exposure as the standard subfrontal and frontotemporal approaches, with only minimal invasive access. The corridor created by the eyelid approach carries the advantage of providing a more direct working angle to various anterior skull base lesions, sometimes superseding the indirect lateral corridor provided by the usual frontotemporal craniotomy. Through a supraorbital craniotomy, anterior fossa lesions both ipsilateral and contralateral to the craniotomy can be easily approached; however, the major limitation remains the vertical extent of the lesions.[13]

Supraorbital frontal craniotomy implements an adequate exposure of the skull base, extending from the cribriform plate to the mesiotemporal lobe and ventral brainstem. It provided a gateway to the corresponding anterior cranial fossa, sphenoid wing ridge, basal frontal lobe and frontal pole, medial temporal lobe, lateral wall of cavernous sinus, proximal Sylvian fissure, suprasellar/parasellar region, interpeduncular cistern, medial or superior aspect of contralateral optic nerve, chiasm, and internal carotid artery [

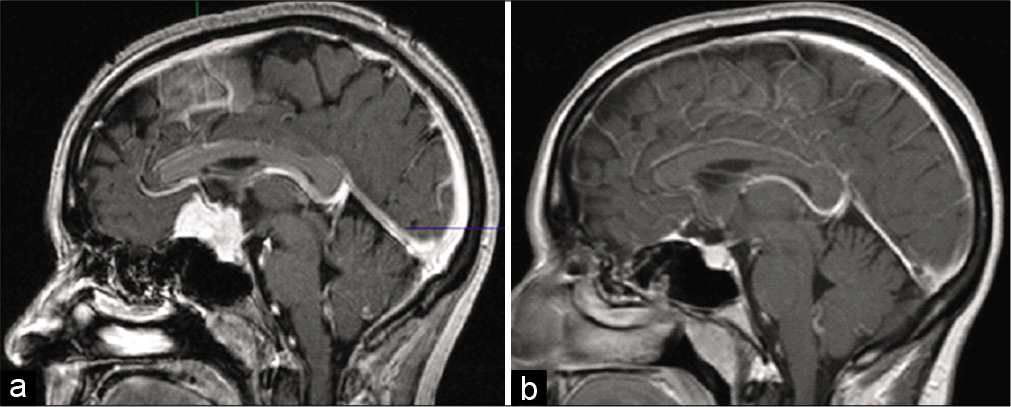

Figure 2:

(a) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T1 with contrast, Sagittal view, of a Craniopharyngioma – a 48-year-old with focal field deficits. (b) MRI T1 with contrast, Sagittal view of a 3-months follow-up of the Craniopharyngioma showing gross total resection, stable vision (same as preoperative).

We have adopted the “eyelid” approach since 2007 and had made some of our own modifications to the craniotomy, with the joint effort of an oculoplastic neuro-ophthalmologist. In the 10-year period from 2007 to 2016, we have successfully completed 126 eyelid approach cases, with 83 vascular cases, and 44 tumor cases, which is the current topic for our article. We highlight our experience with the approach in managing various skull base tumors, in addition to other intracranial tumors within the accessible confinements by the approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Methods

With approval from our Institutional Review Board for this study and waiver of patient consent, we retrospectively reviewed the records for patients that underwent the eyelid approach between 2007 and 2016. Forty-four intracranial nonvascular intracranial lesions, mostly skull base, were operated on through supraorbital frontal minicraniotomy through the eyelid incision, performed by a single neurosurgeon with the collaboration of an oculoplastic surgeon, for openings and closures, using previously reported modified technique.[1]

Outcome variables recorded included the extent of tumor excision, postoperative complications, including hemorrhage or other neurological deficits, wound healing, and incisional cosmoses. Cosmetic outcomes were qualitative based on mainly the patient and the surgeon’s assessment (e.g., ptosis, visible scarring, skin dimpling, or temporal wasting). Postoperative cosmetic outcomes are recorded at 1–2 weeks following discharge after the initial periorbital swelling has resolved and at 3–6 months follow-up visit in outpatient clinic. Patients are examined with both eyes open at 3–6 feet to determine whether there is any noticeable asymmetry of the periorbital facial areas between the operative side and the virgin contralateral side secondary to scarring or ptosis. Outcomes are judged solely subjectively based on the physical examination of the primary surgeon (Dr. Aziz) and the subjective assessment of the patient and/or patient’s family.

The extent of tumor resection was defined by a combination of primary surgeon’s observation noted in the operative report and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies acquired for the patients. Any potential residual noted in the MRI is confirmed both by the surgeon and the neuroradiology staff at our institution. In our series, we utilize the Simpson grading system to describe the skull base meningioma outcomes.[23] Grade 1 is defined as complete removal of the tumor along with its dural base and any affected calvarium. Grade II is defined as gross total resection with coagulation of the entire dural base. Grade III is defined as gross total resection with coagulation or resection of the dural base. Grade IV is defined as a subtotal resection, while Grade V is defined as a debulking and decompression procedure with biopsy of lesion.

Patient selection

With the minimally invasive advantages, very little limitations were applied in case selections. Patient’s age and preoperative medical morbidities were not significant exclusion criteria for surgery. Both neoplastic and vascular lesions can thus be treated through this approach; however, in our current study, we report our tumor cases only. Nonvascular pathologies within the anterior and middle skull base regions, mainly small- to medium-sized meningioma (1–4 cm, with special consideration to vertical extent) of the cribriform plate as well as the planum and suprasellar regions, craniopharyngiomas, optic nerve lesions, suprasellar/parasellar pituitary adenomas, and some other intraparenchymal neoplastic lesions.

RESULTS

There were 44 patients operated on using the supraorbital frontal minicraniotomy through the eyelid incision for the managing various intracranial tumors during the 10-year period (2007–2016). We had 16 male and 28 female patients (1:2.3 male-female ratios). Mean age was 53.1 (median 54 years), with an age range from 12 to 80 years.

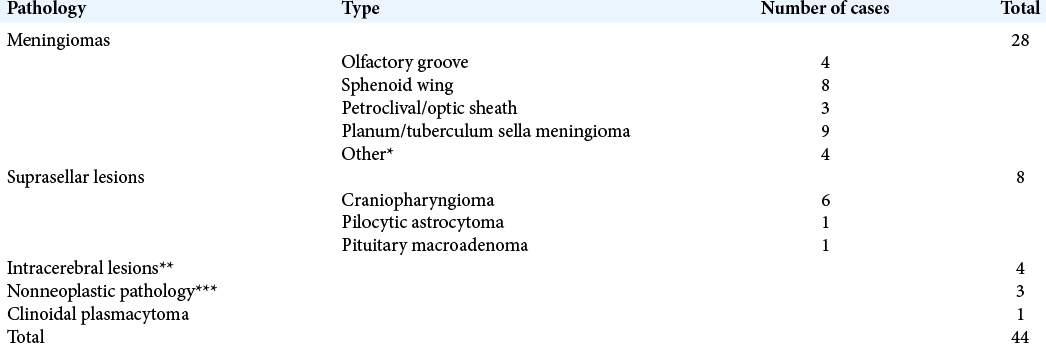

Of the 44 patients operated on, there were 19 anterior skull base lesions, eight middle skull base lesions, and eight parasellar lesions. The most common pathology encountered was anterior skull base meningiomas followed by craniopharyngiomas. Various intracerebral frontal lesions were resected including one cavernoma, two astrocytoma, and one oligodendroglia. A complete breakdown to all encountered pathologies is presented in [

All surgeries were performed with the surgical microscope. Beginning from our fifth case, opening time was about 45–60 min and closure time from dura to skin was about 45–60 min. The average hospital length of stay was 6.4 days with a standard deviation of 1.9 days. While most patients generally tolerated their skull base surgery very well with minimal postoperative pain, given the natural soft-tissue swelling of the periorbital wound and the poor quality of the fronto-orbital dura and the difficulty achieving a water- tight intraoperative dural closure, we often kept the patients several days longer to monitor any possible development of a pseudomeningocele. In rare cases, patients did develop a small pseudomeningocele or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks that generally resolved with CSF diversion through a lumbar drain during their initial postoperative stay.

As regard tumor resection, meningiomas were resected as follows; Simpson Grade I/II was achieved in 20 cases, and Simpson Grade III/IV in eight cases based on postoperative MRI. For the Grade 3 resections, two out of the 7, Grade III resections were optic sheathe meningiomas which are notoriously difficult/impossible to get gross total resection due to their diffuse nature; the other five cases had a max dimension ranging from 3.5 to 5.8 cm (average 3.9 cm). For all other variant lesions, gross total resection was achieved in 12 cases, and subtotal resection was achieved in four cases which comprised large parasellar tumors (two craniopharyngiomas, one pilocytic astrocytoma, and one pituitary macroadenoma).

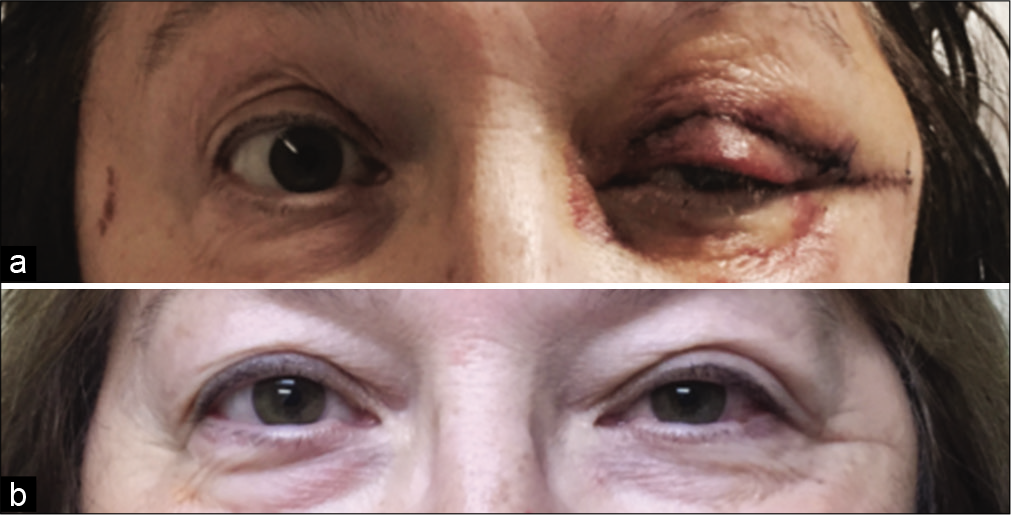

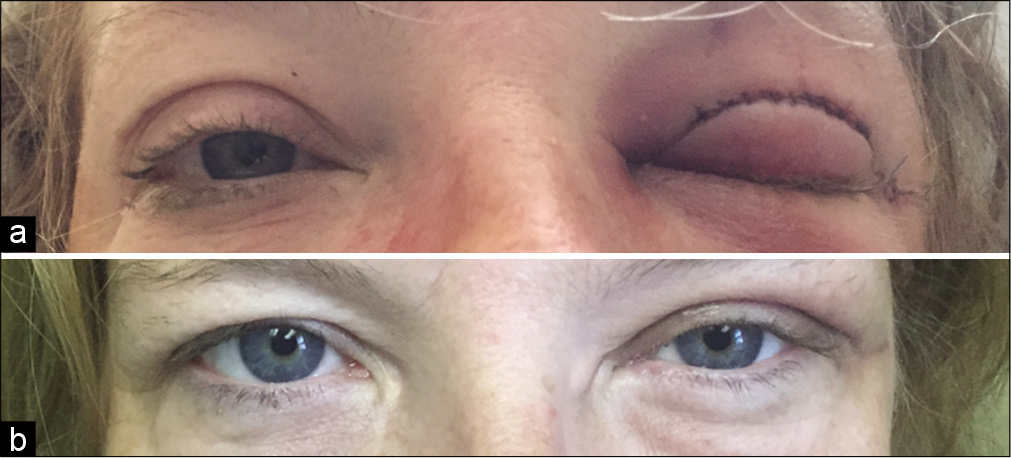

Overall, 43 of our 44 patients whom were operated on through the eyelid approach had excellent cosmetic results that included well-healed incisions with no noticeable incision line, scarring, or temporalis atrophy at follow-up. This is thought to be due to the inherently good skin healing of the eyelid region. One case had suboptimal outcome that was an early patient in our series (third case). The poor cosmesis was attributed to the temporalis wasting rather than incisional scarring itself. Despite of this case, other complications that required wound revision ultimately and uniformly still resulted in excellent cosmesis. Examples of postoperative skin incision follow-up are seen in

Our data reflect the relative safety that the eyelid approach may provide; with no major surgical postoperative complication such as strokes, significant neurologic deficits, or major postoperative hematomas reported. We did report three cases with considerable complications. That included; one case developing late onset pseudomeningocele, two cases of deep wound infection, and another case suffered facial pain. We also recorded four cases that required CSF diversion methods in early postoperative days to control leaks. Our toughest complication was seen in one of our earliest patients (third case in series), who developed a subfrontal pseudomeningocele at 3 months postoperative that required open duro/cranioplasty. Unfortunately, at 5 months postoperatively she developed an eyelid abscess, which required incision and drainage in the operating room. At later follow-up, she suffered right side temporalis muscle wasting which ultimately required neuroplasty and a fat graft 2 years after her initial surgery.

Another case developed wound infection that required surgical wound revision but eventually healed well without visible scarring at follow-up. Our third complication case had postoperative onset trigeminal nerve V1 distribution facial pain. With her follow-up, she started to complain from additional V2 and V3 and later occipital pain, which we could not relate to the surgery, and attributed to chronic facial pain that required individual surgical treatments later on by our surgical team. Our patient’s follow-up ranged from 3 to 69 months, during which two patients expired of natural causes.

DISCUSSION

We have usefully adapted our modified fronto-orbital approach through “eyelid” incision in managing a large number of cases with various anterior and middle skull base lesions over 10 years. The increasing familiarity and growing experience with the approach and its feasibility have granted us the ability to manage a large variety of lesions, spanning all over the anterior, and to a lesser extent middle skull base region. We were able to successfully treat 44 cases with a complication rate of 6.8% that is similar to rates reported in the much larger case series reported by Reisch and Perneczky utilizing their eyebrow approach.[9] We have rarely needed to resort to using the traditional orbitofrontal or frontotemporal craniotomy except in rare, large tumors >4–6 cm in size, particularly in the vertical dimension.[13]

Access to the anterior cranial vault pathologies through a bicoronal scalp flap and variations of the fronto-orbital craniotomy is well established. However, they involve extensive incisions, craniotomies, and frontal lobe retraction, to achieve the required surgical extension. On the contrary, Perneczky, one of the pioneers of minimally invasive neurosurgery stated that the “surgical approach should be as large as necessary and as small as possible,” hence harboring the minimally invasive approaches tends to predominate.[16]

Minimally invasive approaches are gaining larger acceptance every day. It has allowed accessing pathologies with decreased collateral soft-tissue retractions and dissections with minimal craniotomies, compared to open techniques. Multiple experiences have been reported in the past two decades with low rates of wound infection, improved postoperative incisional pain, decreased hospital stay, and good wound healing.[10,18] Besides all mentioned advantages of the minimally invasive approach, excellent cosmetic outcome should be an achievable goal of the minimally invasive approach.[5]

Jho[4] first reported the successful use of the fronto-orbital craniotomy through an eyebrow incision in a series of 11 cases. This was followed by Perneczky who developed and popularized the supraorbital “keyhole” approach to access the anterior cranial fossa. He described his institutional experience with the technique in 2005 across 471 cases.[16,18,19] Both surgeons’ achievements have added a new gateway to approach this region of the brain with minimal invasive advantages and an increased extent and angle of exposure. This has opened the way for other surgeons to adopt and even further modify the approach.[4,5,7]

Later, another fronto-orbital approach modification was proposed by Andaluz et al.[2] He described the access through a transpalpebral access. He described incising at the natural skin crease of the upper eyelid allows the surgeon to perform a minicraniotomy and provided exposure similar to the eyebrow incision. This was followed by single institutional experience with the approach with additional modifications, particularly with the one-piece bone flap achieved using our special designated chisel[1] currently adopted in this study.

The 10-year experience reported here presents a substantial number of patients who continue to demonstrate good outcomes. From our overall case series of 44 tumor patients, we report an excellent cosmetic outcome in 97.7% of these cases. While both eyelid and eyebrow incisions heal quickly; however, the eyelid incision is naturally masked by the suprasternal crease and does not carry the risk of focal eyebrow alopecia. In addition, to optimize bone flap repositioning, we use injectable bone substitute to fill the gaps around the flap after securing it with low-profile titanium plates.[11]

Nonetheless, utilization of the upper eyelid crease was not new, nor unique. It was reported to be extensively used by oculoplastic surgeons in managing various pathologies since the year 2000.[3,9,17,20] The superior incision of a cosmetic blepharoplasty encouraged Gassner et al. to further modify the incision and used an incision about 7–12 mm above the supratarsal fold, which makes the corridor to the anterior skull base larger, due to the more superior placement of the incision, and stated even better cosmetic outcome.[6]

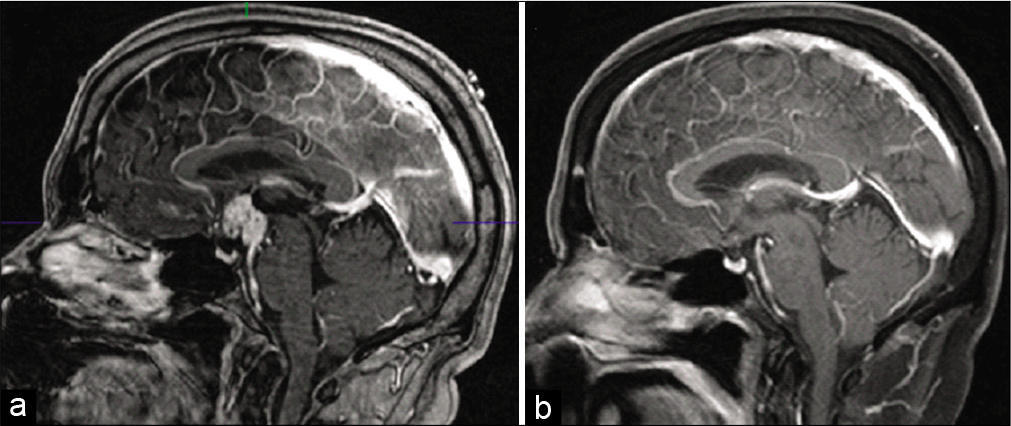

A wide variety of pathologies were managed during the 10 years’ experience, which clearly reflected the advantages of the offered surgical corridor. In general, a gross total resection was achieved in 72.2% of the cases. Cases ranged from skull base meningiomas (Tuberculum sellar/ planum – [

The surgical approach we adopted in our experience describes a direct access to anterior cranial vault lesions, with some extra access that could be achieved to the middle cranial base. The offered mini-craniotomy approach is minimally disruptive, providing excellent exposure, and longer working corridor along the basal cavity. As a result, lesions were accessed without the need for extensive and prolonged frontal lobe retraction. No major surgical postoperative complication such as strokes, significant neurologic deficits, or major postoperative hematomas was experienced. Deep wound infection was seen in two cases (4.5%), a slightly higher rate compared to 3.2% reported in the previous publications.[1,12] A rate of 1.3–2.7% wound infection rate was reported in large transciliary case series.[9,15] Only one case (2.27%) of late postoperative CSF leak with pseudomeningocele was reported and managed surgically.

Although good results have been reported using the eyebrow incisions, forehead numbness is a common, sometimes permanent, and complaint seen in the early postoperative period. Frontalis palsy represents another early postoperative problem often seen after eyebrow incisions; both happen presumably due to incision retraction, and subsequently overstretching the supraorbital and frontal branch of the facial nerves. In a series by Reish and Perneczky they reported a 7.5% incidence of transient numbness and a 5.5% incidence of permanent frontalis weakness.[19]

In our experience, we did not observe this potential problem likely because the eyelid provides a wider and safer margin for the frontal branch of facial nerve from being injured when compared to the eyebrow incision. It also allowed a further 1.5 cm of lateral extension beyond lateral canthus (crow’s feet skin crease), with minimal risk to injure the frontal branch of the facial nerve.[22] This lateral extension provides extra working space for managing lateral lesions, or lesions with lateral extensions lesions. In our patients, only two developed some sort of similar problem, where they developed postoperative facial pain that was only temporary in one, and needed further management in the second.

The eyelid approach, just like any other approach, harbors inherent technical limitations which need to be addressed. Like other keyhole approaches, achieving adequate illumination into the corridor can be problematic and necessitates frequent microscope and operative bed adjustments. Incorporating the endoscope is a possible solution for this limitation which was not utilized in our experience. One other possible limitation would be the building of a team, with a neuro-ophthalmologist, who is considered an important aspect of the approach. Based on our experience with the eyelid incision, we have found this approach to be a relatively versatile tool for approaching various intra-axial and extra-axial lesions of the anterior skull base.

Although, we were able to manage intracerebral fronto- basal lesions such as gliomas and cavernomas, and various common skull base meningiomas, the suprasellar region (cisterns) was not as accessible. Neoplastic suprasellar lesions such as pituitary macroadenoma and extreme craniopharyngiomas presented a relative limitation to the approach. This clearly indicates that the primary anatomic limitations of our approach remain the vertical and lateral extension of the lesion due to the limitation in work angle in a single-stage surgical setting which generally restricts the maximum dimension to approximately 6 cm.

Our study also carries some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Our study is a retrospective analysis of various benign and malignant intracranial lesions. Furthermore, long-term patient outcome and recurrence rate in benign tumors with subtotal or near- total removal were not analyzed thoroughly, due to relatively short follow-up. Furthermore, our cosmetic outcomes are measured on a subjective rather than objective scale, which is also a relative limitation of the study. This eyelid incision approach was considered as a general strategy for all anterior skull base pathologies. At our institution, we do not routinely perform other minimally invasive craniotomy techniques, which could have allowed for a direct comparison between these minimally invasive techniques. Although the eyelid technique has proven versatile at our institution, our results should be interpreted in the context of patient selection strategy and according to the main surgeon’s approach preference, and not be considered as a general strategy for all anterior intracranial tumors.

CONCLUSION

The supraorbital frontal modified craniotomy through the eyelid approach continues to be an applicable option to approach anterior intracranial lesions, after mastering the technique. The minimally invasive access through the eyelid involves dissection in normal tissue planes with minimal surgical trauma, less postoperative pain, and excellent cosmetic results. In addition, the multidisciplinary team of a neurosurgeon and oculoplastic surgeon, uniquely proposed by our practice, working together ensures the maximum degree of safety and proficiency during the soft-tissue wound exposure and closure, as well as intracranial portion of the operation. Our 10-year experience supports the approach’s versatility as a technique that can address many lesions. Nevertheless, the debate of whether it’s advantageous over the eyebrow approach is justifiable. Both should be a part of the neurosurgical artillery. Future directions for research will focus on addressing differences and limitations of using a microscope versus endoscopic visualization for this approach.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Abdel Aziz KM, Bhatia S, Tantawy MH, Sekula R, Keller JT, Froelich S. Minimally invasive transpalpebral “eyelid” approach to the anterior cranial base. Neurosurgery. 2011. 69: ons195-206

2. Andaluz N, Romano A, Reddy LV, Zuccarello M. Eyelid approach to the anterior cranial base. J Neurosurg. 2008. 109: 341-6

3. Bergeron CM, Moe KS. The evaluation and treatment of upper eyelid paralysis. Facial Plast Surg. 2008. 24: 220-30

4. Czirjak S, Szeifert GT. Surgical experience with frontolateral keyhole craniotomy through a superciliary skin incision. Neurosurgery. 2001. 48: 145-9

5. Dare AO, Landi MK, Lopes DK, Grand W. Eyebrow incision for combined orbital osteotomy and supraorbital minicraniotomy: Application to aneurysms of the anterior circulation: Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2001. 95: 714-8

6. Gassner HG, Schwan F, Schebesch KM, Boahene K, Quiñones-Hinojosa A.editors. Transorbital approaches: Minimally invasive access to the anterior skull base. Minimal Access Skull Base Surgery: Open and Endoscopic Assisted Approaches. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2015. p. 62-72

7. Jallo GI, Bognar L. Eyebrow surgery: The supraciliary craniotomy: Technical note. Neurosurgery. 2006. 59: 157-8

8. Jho HD. Orbital roof craniotomy via an eyebrow incision: A simplified anterior skull base approach. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 1997. 40: 91-7

9. Kersten RC. The eyelid crease approach to superficial lateral dermoid cysts. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1988. 25: 48-51

10. Mandel M, Tutihashi R, Mandel SA, Teixeira MJ, Figueiredo EG. Minimally invasive transpalpebral “‘Eyelid” approach to unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2017. 13: 453-64

11. Mao G, Aldahak N, Aziz KA, Evans J, Kenning T, Farrell C.editors. Keyhole supraorbital craniotomy: Eyelid and eyebrow approaches. Endoscopic and Keyhole Cranial Base Surgery. Switzerland, Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 129-39

12. Mao G, Gigliotti M, Aziz K, Aziz K. Transpalpebral approach. “eyelid incision” for surgical treatment of intracerebral aneurysms: Lessons learned during a 10-year experience. Neurosurgery. 2019. 18: 309-15

13. Mao G, Yu A, Aziz KA, Garcia H, Evans J.editors. Tuberculum sellae. Skull Base Surgery: Strategies. New York: Thieme; 2019. p. 3-18

14. Mitchell P, Vindlacheruvu RR, Mahmood K, Ashpole RD, Grivas A, Mendelow AD. Supraorbital eyebrow minicraniotomy for anterior circulation aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2005. 63: 47-51

15. Ohjimi H, Taniguchi Y, Tanahashi S, Era K, Fukushima T. Accessing the orbital roof via an eyelid incision: The transpalpebral approach. Skull Base Surg. 2005. 10: 211-6

16. Perneczky A, Muller-Forell W, Lindert E, Fries G.editors. Keyhole Concept in Neurosurgery: With Endoscope-Assisted Microsurgery and Case Studies. New York: Thieme; 1999. p.

17. Perneczky A.editors. Surgical Results, Complications and Patient Satisfaction after a Supraorbital Craniotomy through Eyebrow Skin Incision. Koln, Germany: Joint Meeting Mit der Ungarischen Gesellschaft fur Neurochirurgie Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Neurochirurgie; 2004. p.

18. Reisch R, Perneczky A, Filippi R. Surgical technique of the supraorbital key-hole craniotomy. Surg Neurol. 2003. 59: 223-2

19. Reisch R, Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery. 2005. 57: 242-55

20. Richter DF, Stoff A, Olivari N. Transpalpebral decompression of endocrine ophthalmopathy by intraorbital fat removal (Olivari technique): Experience and progression after more than 3000 operations over 20 years. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007. 120: 109-23

21. Sánchez-Vázquez MA, Barrera-Calatayud P, Mejia-Villela M, Palma-Silva JF, Juan-Carachure I, Gomez-Aguilar JM. Transciliary subfrontal craniotomy for anterior skull base lesions: Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1999. 91: 892-6

22. Schmidt BL, Pogrel MA, Hakim-Faal Z. The course of the temporal branch of the facial nerve in the periorbital region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001. 59: 178-84

23. Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1957. 20: 22-39

24. Velimir L, Sajko T, Beros V, Kudelic N, Velimir L Jr. Advantages and disadvantages of the supraorbital keyhole approach to intracranial aneurysms. Acta Clin Croat. 2006. 45: 91-4