- Department of Neurosurgery, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Department of Ophthalmology, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Department of Neuroradiology, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

Correspondence Address:

Daniel Kiss-Bodolay, Department of Neurosurgery, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_180_2023

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Daniel Kiss-Bodolay1, Heimo Steffen2, María Isabel Vargas3, Karl Schaller1. The use of diffusion magnetic resonance imaging tractography in supporting anatomical conflict between an uncal protrusion and the oculomotor nerve: A case report of isolated inferior rectus palsy. 02-Jun-2023;14:194

How to cite this URL: Daniel Kiss-Bodolay1, Heimo Steffen2, María Isabel Vargas3, Karl Schaller1. The use of diffusion magnetic resonance imaging tractography in supporting anatomical conflict between an uncal protrusion and the oculomotor nerve: A case report of isolated inferior rectus palsy. 02-Jun-2023;14:194. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12342/

Abstract

Background: Isolated inferior rectus muscle palsy is a rare entity and even more rarely induced by an anatomical conflict. We report here a clinical case of third cranial nerve (CN III) compression in its cisternal segment by an idiopathic uncal protrusion in a patient presenting an isolated inferior rectus muscle palsy.

Case Description: We report a case of an anatomical conflict between the uncus and the CN III in the form of a protrusion and highly asymmetrical proximity of the uncus and asymmetrically thinned nerve diameter deviated from its straight cisternal trajectory on the ipsilateral side were supported by an altered diffusion tractography along the concerned CN III. Clinical description, review of the literature, and image analysis were done including CN III fiber reconstruction using a fused image from diffusion tensor imaging images, constructive interference in steady state, and T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images on a dedicated software (BrainLAB AG).

Conclusion: This case illustrates the importance of anatomical-clinical correlation in cases of CN deficits and supports the use of new neuroradiologically based interrogation methods such as CN diffusion tractography to support anatomical CN conflicts.

Keywords: Cranial nerve, Diffusion tractography, Inferior rectus palsy, Uncal protrusion

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic herniation or protrusion of the uncus out of the life-threatening situation is a rarely reported anatomical variation.[

Here, we report the use of nerve tractography in the work up of an isolated inferior rectus muscle palsy detecting decreased functional anisotropy in a thinned and compressed CN III in its cisternal segment with no identified vascular or neurological underlying disease but an idiopathic uncal protrusion ipsilaterally.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our case description is based on medical and imaging data analyzed retrospectively. After confirmation of the oculomotor deficit by the ophthalmologist, complementary MR diffusion tractography was performed prospectively. Fiber reconstruction was made using a fused image from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) images and T2-fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images on a dedicated software (BrainLAB AG). Fibers were reconstructed based on two selected region of interest (ROI) placed along the cisternal segments of the CN III including: the interpeduncular one, the one facing the uncus, and lastly the one before joining the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. Fiber length, angulation, and functional anisotropy thresholds were set to reconstruct as much fibers as possible: minimum functional anisotropy (FA) 0.01; minimum length 1 mm; maximum angulation 28°. In addition, measurements were done on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images using Weasis DICOM viewer (Weasis, HUG) using a single ROI placed on the CN III in its cisternal segment between the interpeduncular cistern and its own cistern in a rostral direction.

RESULTS

We report here the case of a male patient in his fifties followed at an outpatient clinic since a few years for the progressive development of a diplopia in the downward gaze. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed no intraorbital lesion but a millimetric right parapontine contrast-enhancing spot compatible with a small meningioma possibly affecting the right CN IV. The diagnosis of right CN IV palsy induced by a millimetric parapontine meningioma settled.

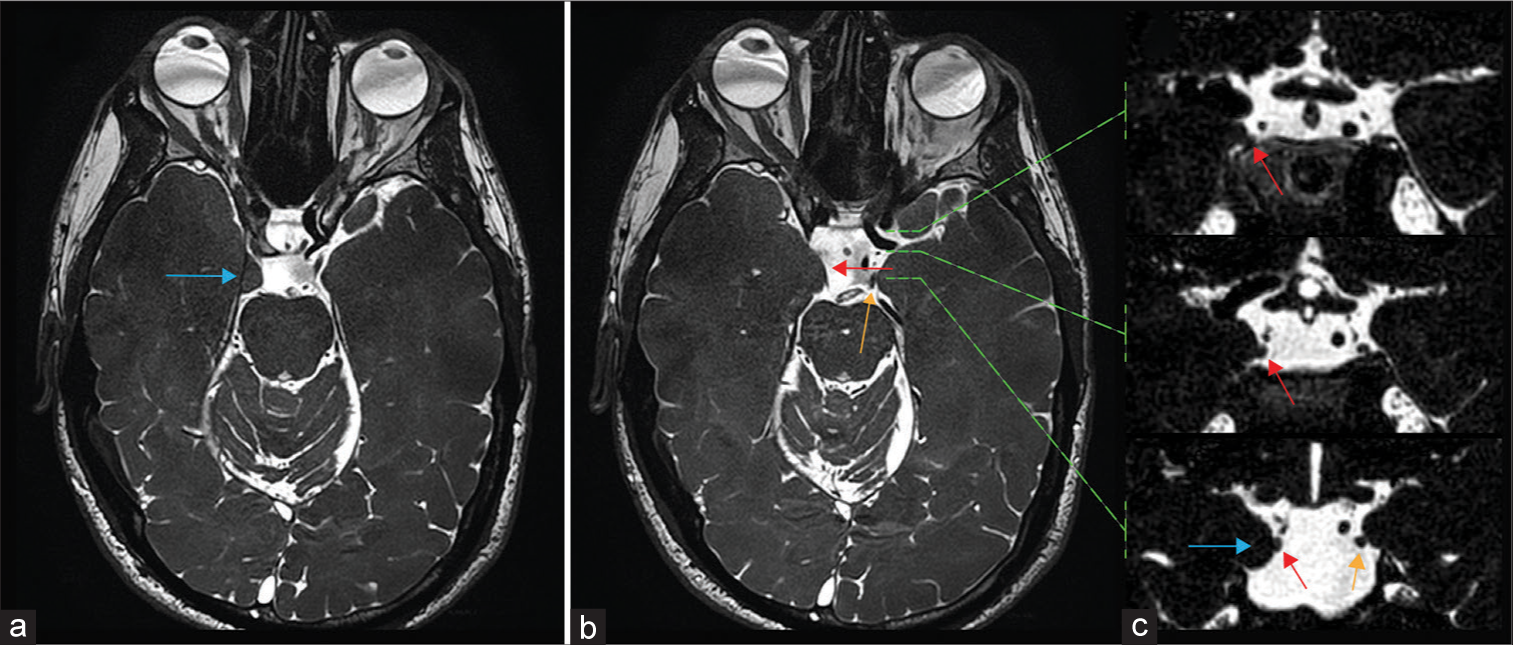

In 2021, we received the patient at our outpatient neurosurgical clinic for a first follow-up consultation and found an isolated limitation of downgaze of the right eye that was more important in abduction than in adduction. Pupillary function was normal. These findings are consistent with an isolated right inferior rectus muscle palsy. Reviewing the MRI images with our attending neuroradiologist, the parapontine lesion was confirmed to be most likely a CN IV schwannoma, no ischemic lesion or myelin abnormality was detected on diffusion or FLAIR images and no intraorbital lesion or muscle asymmetry was seen. Finally, no signs of systemic disease were present. However, we found a thinner right CN III pushed medially in its perichiasmatic cisternal segment [

Figure 1:

T2 constructive interference in steady state magnetic resonance imaging axial and corresponding coronal images illustrating the anatomical conflict between the uncus (blue arrow) and the third cranial nerve (CN III) (red arrow) when compared to the left CN III (orange arrow): (a) axial view showing the uncal protrusion; (b) axial image illustrating the anatomical conflict between the right CN III and the uncus, notice the thinner aspect of the right CN III on its mediolateral axis when compared to the left side on axial plans; and (c) coronal plans illustrating the uncus-CN III prolonged contact in the chiasmatic cistern, absent on the left side. Axial green dashed lines indicate the corresponding coronal anatomical planes.

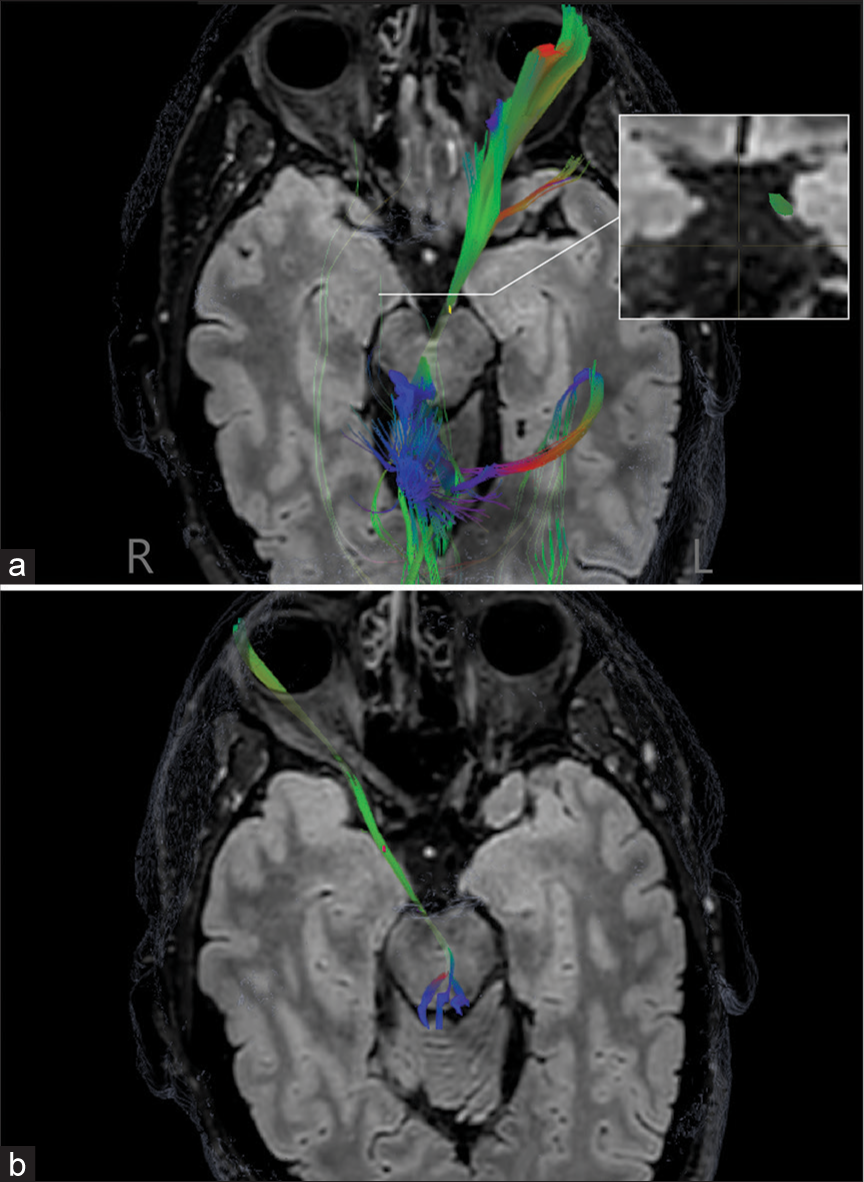

To further analyze the finding of a thinner IIIrd CN using newly obtained DTI images, we reconstructed the fibers passing through the CN III on both sides using two ROI placed along the nerve before and after the cisternal segment facing the uncus. Using the same fiber length, angulation, and functional anisotropy thresholds, no fibers could be reconstructed on coronal sections on the right side even after > 10 attempts, in contrary to the left side, where all attempts could reconstruct fibers with an average FA of 0.27 [

Figure 2:

Diffusion tensor imaging diffusion image-based fiber reconstructions fused with T2 Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images obtained from two region of interest placed on two different cisternal segments of the third cranial nerve: (a) axial view of fiber reconstruction on the left with an example of fiber reconstruction obtained on coronal sections and (b) axial view of fiber reconstruction on the right. Red: Transverse fibres, Green: Anteroposterior fibres, Blue: Craniocaudal fibres.

At the end, we sent our patient to pass a complete neuroophthalmological examination confirming the isolated right inferior rectus muscle palsy. The diplopia was compensated by the patient adopting a slight head tilt. A small prism was prescribed to reduce diplopia perception in downgaze and thus decreased the head tilt. Eye muscle surgery was not considered due to the small impact of diplopia and the patient was reassured concerning his diagnosis. A radioclinical follow-up was scheduled for the small CN IV schwannoma even though it showed no volumetric growth in 5 years.

DISCUSSION

We report here a rare case of symptomatic idiopathic uncal protrusion affecting the CN III in its cisternal segment in the clinical context of an isolated inferior rectus muscle palsy. We were not able to detect any intra-axial ischemic lesion nor systemic disease or intraorbital lesion that could explain the isolated inferior rectus muscle palsy. So far isolated injury of the fibers innervating the inferior rectus muscle in its cisternal segment has never been reported. Diffusion tractography is known to be a sensitive study method to visualize the anatomical integrity of CNs.[

CONCLUSION

This case illustrates the importance of anatomical-clinical correlation in cases of CN deficits and supports the use of new neuroradiologically based interrogation methods such as CN diffusion tractography to support anatomical CN conflicts.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Castro O, Johnson LN, Mamourian AC. Isolated inferior oblique paresis from brain-stem infarction. Perspective on oculomotor fascicular organization in the ventral midbrain tegmentum. Arch Neurol. 1990. 47: 235-7

2. Choi KD, Choi JH, Choi HY, Choi HY, Huh YE, Kim HJ. Inferior rectus palsy as an isolated ocular motor sign: Acquired etiologies and outcome. J Neurol. 2013. 260: 47-54

3. Goyal S, Pless M. Isolated inferior rectus palsy: A case report and review of literature. Neuroophthalmology. 2009. 33: 63-9

4. Horowitz M, Kassam A, Levy E, Lunsford LD. Misinterpretation of parahippocampal herniation for a posterior fossa tumor: Imaging and intraoperative findings. J Neuroimaging. 2002. 12: 78-9

5. Jacquesson T, Frindel C, Kocevar G, Berhouma M, Jouanneau E, Attyé A. Overcoming challenges of cranial nerve tractography: A targeted review. Neurosurgery. 2019. 84: 313-25

6. Ksiazek SM, Slamovits TL, Rosen CE, Burde RM, Parisi F. Fascicular arrangement in partial oculomotor paresis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994. 118: 97-103

7. Ram CP, Sherry R. Nonemergent descending transtentorial temporal lobe herniations-case reports of idiopathic [Bilateral uncal] and chronic [unilateral uncal and parahippocampal] herniations with review of literature. J Med Imaging Case Rep. 2020. 4: 4-8

8. Wilson-Pauwels L, editors. Cranial Nerves: Function and Dysfunction. House, Shelton, Conn: People’s Medical Pub; 2010. p. 55-73

9. Yavarian Y, Bayat M, Frøkjær JB. Herniation of uncus and parahippocampal gyrus: An accidental finding on magnetic resonance imaging of cerebrum. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2015. 4: 2047981614560077

10. Yoshino M, Abhinav K, Yeh FC, Panesar S, Fernandes D, Pathak S. Visualization of cranial nerves using high-definition fiber tractography. Neurosurgery. 2016. 79: 146-65