- Department of Neurological Surgery, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, USA

Correspondence Address:

Rizwan A. Tahir

Department of Neurological Surgery, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.183492

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Tahir RA, Pabaney AH. Therapeutic hypothermia and ischemic stroke: A literature review. Surg Neurol Int 03-Jun-2016;7:

How to cite this URL: Tahir RA, Pabaney AH. Therapeutic hypothermia and ischemic stroke: A literature review. Surg Neurol Int 03-Jun-2016;7:. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/therapeutic-hypothermia-and-ischemic-stroke-a-literature-review/

Abstract

Background:Ischemic stroke is the fifth leading cause of death in the US. Clinical techniques aimed at helping to reduce the morbidity associated with stroke have been studied extensively, including therapeutic hypothermia. In this study, the authors review the literature regarding the role of therapeutic hypothermia in ischemic stroke to appreciate the evolution of hypothermia technology over several decades and to critically analyze several early clinical studies to validate its use in ischemic stroke.

Methods:A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar databases. Search terms included “hypothermia and ischemic stroke” and “therapeutic hypothermia.” A comprehensive search of the current clinical trials using clinicaltrials.gov was conducted using the keywords “stroke and hypothermia” to evaluate early and ongoing clinical trials utilizing hypothermia in ischemic stroke.

Results:A comprehensive review of the evolution of hypothermia in stroke and the current status of this treatment was performed. Clinical studies were critically analyzed to appreciate their strengths and pitfalls. Ongoing and future registered clinical studies were highlighted and analyzed compared to the reported results of previous trials.

Conclusion:Although hypothermia has been used for various purposes over several decades, its efficacy in the treatment of ischemic stroke is debatable. Several trials have proven its safety and feasibility; however, more robust, randomized clinical trials with large volumes of patients are needed to fully establish its utility in the clinical setting.

Keywords: Endovascular, ischemic stroke, neuroprotection, neurovascular surgery, stroke, therapeutic hypothermia

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is a leading cause of disability in most industrialized countries and its economic burden is enormous. The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association currently considers stroke to be the fifth leading cause of death in the US. An estimated 6.6 million Americans over the age of 20 have suffered a stroke. Projections show that, by 2030, an additional 3.4 million people aged ≥18 years will have had a stroke, which is a 20.5% increase in prevalence from 2012.[

METHODS

A comprehensive literature search was performed using both the PubMed and Google Scholar databases to investigate the mechanism of action of therapeutic hypothermia in early animal studies. Search terms included “hypothermia and ischemic stroke” and “therapeutic hypothermia.” Full text versions of the papers included in the review were obtained and independently reviewed by both authors.

A comprehensive search of the recent and current clinical trials utilizing therapeutic hypothermia was performed through the clinicaltrials.gov database. Search terms used included “Stroke and Hypothermia.” Full text versions of the published trials were obtained and independently reviewed by the authors. Studies that were terminated early or aborted were omitted. Non-English articles were omitted for this review. No contact was made with any of the authors of the papers included in this review.

THERAPEUTIC HYPOTHERMIA—WHERE IT ALL STARTED

Therapeutic hypothermia has been used for several years but there is some hesitation to its clinical adaptation worldwide because of the apparent high risk of complications. Only recently has the medical community begun to realize the benefits of therapeutic hypothermia, and its use is now widely propagated for various purposes.

For several decades, therapeutic hypothermia has been used to provide anesthesia during amputations, to prevent cancer cells from multiplying, and to reduce complications during heart surgery.[

THERAPEUTIC HYPOTHERMIA FOR NEUROPROTECTION

Scientists have strived to reduce complication rates related to hypothermia because of the encouraging beneficial effects. Hence, the concept of hypothermia in some way inducing neuroprotection received significant attention in the last several decades, with studies examining this possibility being reported. At present, hypothermia is recognized as perhaps the most robust neuroprotectant in the laboratory to date. However, much of our current knowledge is derived from studies performed on cerebral injury models caused by cardiac arrest rather than stroke. Two large, randomized trials, one from Europe and the other from Australia, are now available that show substantial benefit of mild hypothermia on neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. The Australian study showed that more patients in the hypothermic group had a favorable outcome compared to the normothermic group (49% vs. 26%; P = 0.046).[

The molecular cascades that set in after an ischemic stroke are complex. In the acute stage, the decrease in cerebral blood flow disrupts ionic homoeostasis, leading to increased intracellular calcium and release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Intracellular edema also occurs when sodium and chloride flood the postsynaptic cell.[

HOW DOES HYPOTHERMIA WORK?

Various molecular mechanisms are alleged to be responsible for the beneficial effects of hypothermia in ischemic stroke. Some of the few biological mechanisms responsible for the therapeutic effect of hypothermia include the suppression of dopamine and glutamate release;[

PRECLINICAL ANIMAL STUDIES

The development of relatively simple and reproducible animal models mimicking cerebral ischemia has led to numerous studies investigating the feasibility and efficacy of therapeutic hypothermia. Animal models of focal ischemia usually involve the permanent or reversible unilateral occlusion (for 1–3 hours) of the middle cerebral artery (MCA).[

HUMAN STUDIES

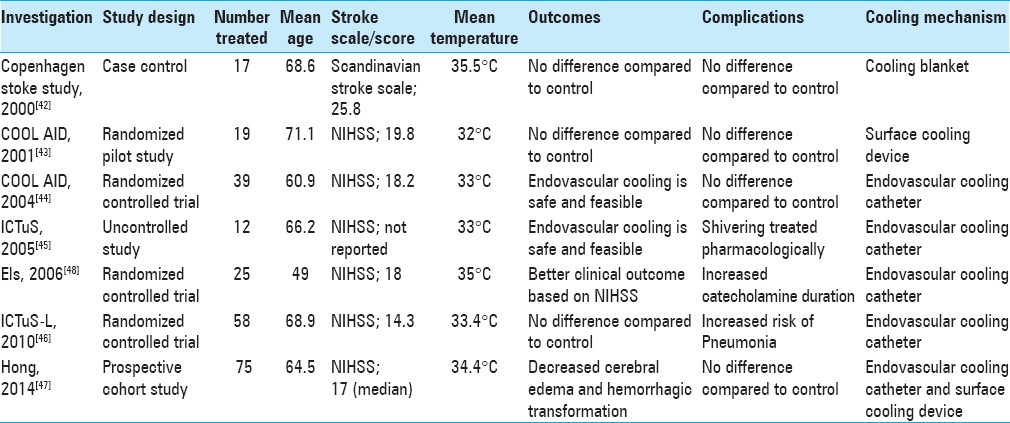

Numerous human studies have been conducted over the past 2 decades investigating the potential therapeutic effects of hypothermia on neuroprotection and improvement in patient outcomes following both ischemic stroke and ischemic stroke with reperfusion. While numerous studies deserve recognition and mention, here, we discuss only those studies that played an important role in the history of therapeutic hypothermia.

In 1998, Schwab et al. published a feasibility and safety study of moderate hypothermia in patients with malignant MCA syndrome. Hypothermia to 33°C was induced within 14 h of stroke onset, and significant reductions in intracranial pressure were noted in all patients.[

Krieger et al. published the first phase of The Cooling for Acute Ischemic Brain Damage (COOL AID) study. This was a pilot study with an open design where authors attempted to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of hypothermia in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Hypothermia was induced by surface cooling utilizing cooling blankets for 12–72 h in patients presenting within 6 h of symptom onset.[

The Intravascular Cooling in the Treatment of Stroke (ICTuS) study was a safety and feasibility trial in which the use of an endovascular cooling system to achieve mild therapeutic hypothermia in awake, acute ischemic stroke patients was assessed; the results were similar to the COOL AID study.[

The Intravenous Thrombolysis Plus Hypothermia for Acute Treatment of Ischemic Stroke (ICTuS-L) study conducted in 2010 was a randomized controlled trial that assessed the safety and feasibility of therapeutic hypothermia using an endovascular cooling catheter in acute ischemic stroke patients presenting within 6 h of symptom onset. The study also tested the safety and feasibility of coupling therapeutic hypothermia with intravenous alteplase.[

In an effort to investigate the effects of therapeutic hypothermia in a neurosurgical context, Els et al., in 2006, showed that hemicraniectomy and hypothermia together resulted in better 6-month functional outcomes based on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) vs. hemicraniectomy alone in ischemic stroke patients with malignant cerebral edema.[

Recently, Hong et al. also showed that 48 h of mild hypothermia and 48 h of rewarming following acute ischemic stroke led to a lower incidence of hemorrhagic transformation, a better outcome measured by the modified Rankin Score, and a lesser degree of malignant cerebral edema.[

EuroHYP-1, a European, multi-centered, phase III randomized controlled trial is currently recruiting participants in order to assess whether 24 h of induced hypothermia to 34–35°C coupled with best medical management results in a better 3-month functional outcome vs. best medical management alone. The study is estimating its enrollment at 1500 participants, which would be one of the largest randomized controlled trials conducted to date on therapeutic hypothermia.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF THERAPEUTIC HYPOTHERMIA

Timing and optimum temperature parameters

Although the optimum timing and duration of hypothermia in human beings is not clear, most active trials attempt to initiate cooling as close to stroke onset as possible. Different levels of hypothermia are defined; mild (>32°C), moderate (28−32°C), deep (20−28°C), profound (5−20°C), and ultraprofound (<5°C) hypothermia. Although the target temperature for cardiac arrest is 32–34°C, target temperature for neuroprotection is unknown. This question was tested in rats by Kollmar et al. who found substantial reduction in the infarct size. Furthermore, improvement in functional outcome was observed in the 33°C and 34°C groups compared with the other temperatures tested.[

Devices and techniques

Rapid advancements have been made in this area. Conventional cooling techniques to induce whole body hypothermia include surface cooling using circulating cold water or fanned cold air, alcohol baths, icepacks, cold water gastric, bladder lavage, ice-water immersion, and cooling blankets. However, these techniques consume a significant amount of time to achieve the target temperature. Because of the apparent drawbacks of surface cooling methods, investigators have examined alternative cooling techniques including endovascular catheters inserted via the femoral vein in the inferior vena cava. Clinical pilot studies in stroke patients show that these catheters provide rapid and precise temperature control.[

Complications

Hypothermia is not a complication-free modality. Cardiovascular compromise, including decreased heart rate, myocardial infarctions, other arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, and reduced cardiac output, has been recorded in previous hypothermia studies.[

CONCLUSION

The American Stroke Association is predicting the prevalence of stroke to increase in the coming decades. Interventional techniques such as endovascular clot retrieval for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke have proved to be effective in reducing the morbidity and mortality of stroke. In addition to such practices, a novel technique such as therapeutic hypothermia may be effective in improving patient outcomes. Early clinical trials such as COOL AID and ICTuS have lent support to its safety and feasibility; however, more evidence is needed to help prove its use in clinical practice.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the United States: A doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011. 42: 1952-5

2. Ao H, Moon JK, Tashiro M, Terasaki H. Delayed platelet dysfunction in prolonged induced canine hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2001. 51: 83-90

3. Baena RC, Busto R, Dietrich WD, Globus MY, Ginsberg MD. Hyperthermia delayed by 24 hours aggravates neuronal damage in rat hippocampus following global ischemia. Neurology. 1997. 48: 768-73

4. Berkhemer OA, Fransen PSS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372: 11-20

5. Bernard SA, Buist M. Induced hypothermia in critical care medicine: A review. Crit Care Med. 2003. 31: 2041-51

6. Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346: 557-63

7. Bigelow WG, Mcbirnie JE. Further experiences with hypothermia for intracardiac surgery in monkeys and groundhogs. Ann Surg. 1953. 137: 361-5

8. Bloch M. Accidental hypothermia. Br Med J. 1967. 2: 376-

9. Buchan AM, Xue D, Slivka A. A new model of temporary focal neocortical ischemia in the rat. Stroke. 1992. 23: 273-9

10. Busto R, Globus MY, Dietrich WD, Martinez E, Valdés I, Ginsberg MD. Effect of mild hypothermia on ischemia-induced release of neurotransmitters and free fatty acids in rat brain. Stroke. 1989. 20: 904-10

11. Ceulemans AG, Zgavc T, Kooijman R, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Sarre S, Michotte Y. The dual role of the neuroinflammatory response after ischemic stroke: Modulatory effects of hypothermia. J Neuroinflammation. 2010. 7: 74-

12. De Georgia MA, Krieger DW, Abou-Chebl A, Devlin TG, Jauss M, Davis SM. Cooling for Acute Ischemic Brain Damage (COOL AID): A feasibility trial of endovascular cooling. Neurology. 2004. 63: 312-7

13. Diringer MN. Treatment of fever in the neurologic intensive care unit with a catheter-based heat exchange system. Crit Care Med. 2004. 32: 559-64

14. Els T, Oehm E, Voigt S, Klisch J, Hetzel A, Kassubek J. Safety and therapeutical benefit of hemicraniectomy combined with mild hypothermia in comparison with hemicraniectomy alone in patients with malignant ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006. 21: 79-85

15. Fay T. Observations on generalized refrigeration in cases of severe cerebral trauma. Res Publ Assos Res Nerv Dis. 1945. 4: 611-9

16. Fay T. Observations on prolonged human refrigeration. NY State J Med. 1940. 40: 1351-4

17. Friedman LK, Ginsberg MD, Belayev L, Busto R, Alonso OF, Lin B. Intraischemic but not postischemic hypothermia prevents non-selective hippocampal downregulation of AMPA and NMDA receptor gene expression after global ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001. 86: 34-47

18. Georgiadis D, Schwarz S, Kollmar R, Schwab S. Endovascular cooling for moderate hypothermia in patients with acute stroke:First results of a novel approach. Stroke. 2001. 32: 2550-3

19. Gingrich MB, Traynelis SF. Serine proteases and brain damage–Is there a link?. Trends Neurosci. 2000. 23: 399-407

20. Globus MY, Busto R, Lin B, Schnippering H, Ginsberg MD. Detection of free radical activity during transient global ischemia and recirculation: Effects of intraischemic brain temperature modulation. J Neurochem. 1995. 65: 1250-6

21. González-Ibarra FP, Varon J, López-Meza EG. Therapeutic hypothermia: Critical review of the molecular mechanisms of action. Front Neurol. 2011. 2: 4-

22. Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372: 1019-30

23. Hamann GF, Burggraf D, Martens HK, Liebetrau M, Jäger G, Wunderlich N. Mild to moderate hypothermia prevents microvascular basal lamina antigen loss in experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2004. 35: 764-9

24. Han HS, Karabiyikoglu M, Kelly S, Sobel RA, Yenari MA. Mild hypothermia inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB translocation in experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003. 23: 589-98

25. Hemmen TM, Raman R, Guluma KZ, Meyer BC, Gomes JA, Cruz-Flores S. Intravenous thrombolysis plus hypothermia for acute treatment of ischemic stroke (ICTuS-L): Final results. Stroke. 2010. 41: 2265-70

26. Hong JM, Lee JS, Song HJ, Jeong HS, Jung HS, Choi HA. Therapeutic hypothermia after recanalization in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014. 45: 134-40

27. Huang F, Zhou L. Effect of mild hypothermia on the changes of cerebral blood flow, brain blood barrier and neuronal injuries following reperfusion of focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Chin Med J (Engl). 1998. 111: 368-72

28. Huang ZG, Xue D, Preston E, Karbalai H, Buchan AM. Biphasic opening of the blood-brain barrier following transient focal ischemia: Effects of hypothermia. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999. 26: 298-304

29. Huh PW, Belayev L, Zhao W, Koch S, Busto R, Ginsberg MD. Comparative neuroprotective efficacy of prolonged moderate intraischemic and postischemic hypothermia in focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosurg. 2000. 92: 91-9

30. . Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002. 346: 549-56

31. Ji X, Luo Y, Ling F, Stetler RA, Lan J, Cao G. Mild hypothermia diminishes oxidative DNA damage and pro-death signaling events after cerebral ischemia: A mechanism for neuroprotection. Front Biosci. 2007. 12: 1737-47

32. Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, Rovira A. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372: 2296-306

33. Kammersgaard LP, Rasmussen BH, Jørgensen HS, Reith J, Weber U, Olsen TS. Feasibility and safety of inducing modest hypothermia in awake patients with acute stroke through surface cooling: A case-control study: The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 2000. 31: 2251-6

34. Kollmar R, Blank T, Han JL, Georgiadis D, Schwab S. Different degrees of hypothermia after experimental stroke: Short- and long-term outcome. Stroke. 2007. 38: 1585-9

35. Krieger DW, De Georgia MA, Abou-Chebl A, Andrefsky JC, Sila CA, Katzan IL. Cooling for acute ischemic brain damage (cool aid): An open pilot study of induced hypothermia in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001. 32: 1847-54

36. Li H, Wang D. Mild hypothermia improves ischemic brain function via attenuating neuronal apoptosis. Brain Res. 2011. 1368: 59-64

37. Lyden PD, Allgren RL, Ng K, Akins P, Meyer B, Al-Sanani F. Intravascular Cooling in the Treatment of Stroke (ICTuS): Early clinical experience. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005. 14: 107-14

38. Mordecai Y, Globus RB, Dietrich WD, Sternau L, Morikawa E, Ginsberg MD, Marangos PJ, Harbans L.editors. Temperature modulation of neuronal injury. Emerging Strategies in Neuroprotection. Boston: Birkhauser; 1992. p. 289-306

39. Morikawa E, Ginsberg MD, Dietrich WD, Duncan RC, Kraydieh S, Globus MY. The significance of brain temperature in focal cerebral ischemia: Histopathological consequences of middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992. 12: 380-9

40. Moyer DJ, Welsh FA, Zager EL. Spontaneous cerebral hypothermia diminishes focal infarction in rat brain. Stroke. 1992. 23: 1812-6

41. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015. 131: e29-322

42. Poli S, Purrucker J, Priglinger M, Ebner M, Sykora M, Diedler J. Rapid Induction of COOLing in Stroke Patients (iCOOL1): A randomised pilot study comparing cold infusions with nasopharyngeal cooling. Crit Care. 2014. 18: 582-

43. Pool JL, Kessler LA. Mechanism and control of centrally induced cardiac irregularities during hypothermia. I. Clinical observations. J Neurosurg. 1958. 15: 52-64

44. Ridenour TR, Warner DS, Todd MM, McAllister AC. Mild hypothermia reduces infarct size resulting from temporary but not permanent focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 1992. 23: 733-8

45. Rosomoff HL, Gilbert R. Brain volume and cerebrospinal fluid pressure during hypothermia. Am J Physiol. 1955. 183: 19-22

46. Rosomoff HL, Holaday DA. Cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen consumption during hypothermia. Am J Physiol. 1954. 179: 85-8

47. Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372: 2285-95

48. Schwab S, Schwarz S, Spranger M, Keller E, Bertram M, Hacke W. Moderate hypothermia in the treatment of patients with severe middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke. 1998. 29: 2461-6

49. . Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995. 333: 1581-7

50. van der Worp HB, Sena ES, Donnan GA, Howells DW, Macleod MR. Hypothermia in animal models of acute ischaemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. 2007. 130: 3063-74

51. Webb WR, Deguzman VC, Grogan JB, Artz CP. Hypothermia: Its effects upon hematologic clearance in experimentally induced staphylococcal bacteremia. Surgery. 1962. 52: 643-7

52. Yamamoto M, Marmarou CR, Stiefel MF, Beaumont A, Marmarou A. Neuroprotective effect of hypothermia on neuronal injury in diffuse traumatic brain injury coupled with hypoxia and hypotension. J Neurotrauma. 1999. 16: 487-500

53. Zhang RL, Chopp M, Chen H, Garcia JH, Zhang ZG. Postischemic (1 hour) hypothermia significantly reduces ischemic cell damage in rats subjected to 2 hours of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 1993. 24: 1235-40