- Department of Neurosurgery, Houston Methodist Neurological Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, Texas, USA.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_438_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Zain Boghani, William III Steele, Sean M. Barber, Jonathan J. Lee, Olumide Sokunbi, J. Bob Blacklock, Todd Trask, Paul Holman. Variability in the size of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor: A magnetic resonance imaging-based analysis. 28-Mar-2020;11:54

How to cite this URL: Zain Boghani, William III Steele, Sean M. Barber, Jonathan J. Lee, Olumide Sokunbi, J. Bob Blacklock, Todd Trask, Paul Holman. Variability in the size of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor: A magnetic resonance imaging-based analysis. 28-Mar-2020;11:54. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9930/

Abstract

Background: A minimally invasive approach to the L2-S1 disc spaces through a single, left-sided, retroperitoneal oblique corridor has been previously described. However, the size of this corridor varies, limiting access to the disc space in certain patients. Here, the authors retrospectively reviewed lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 300 patients to better define the size and variability of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor.

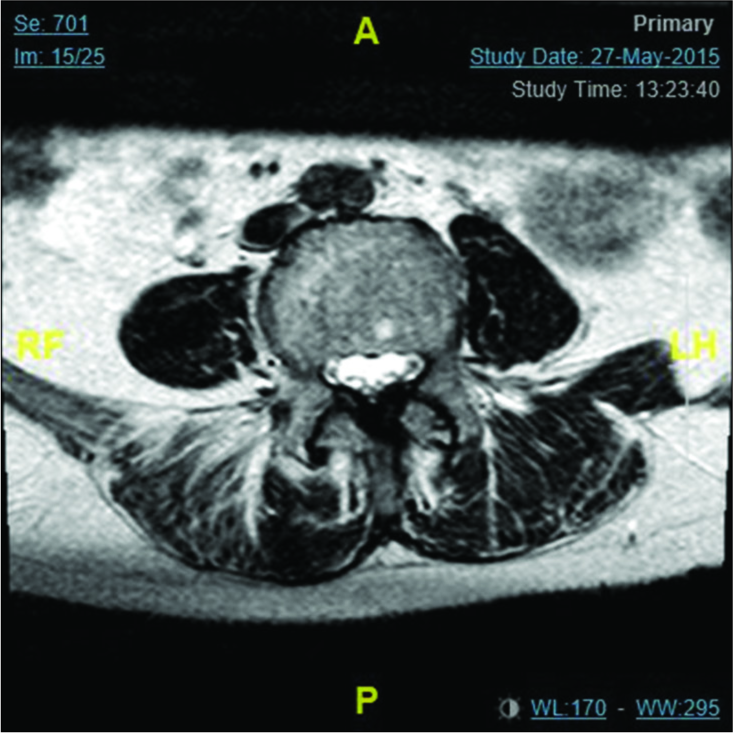

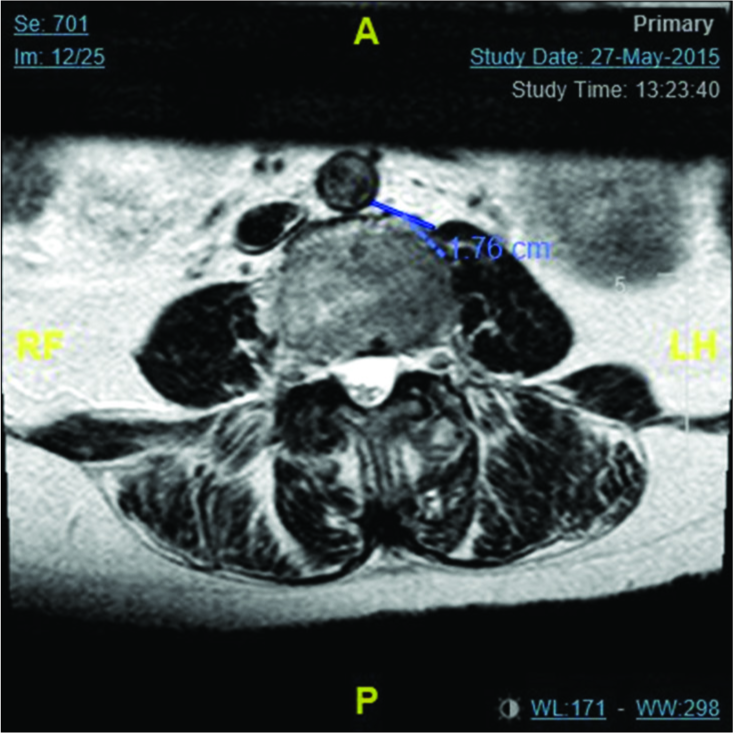

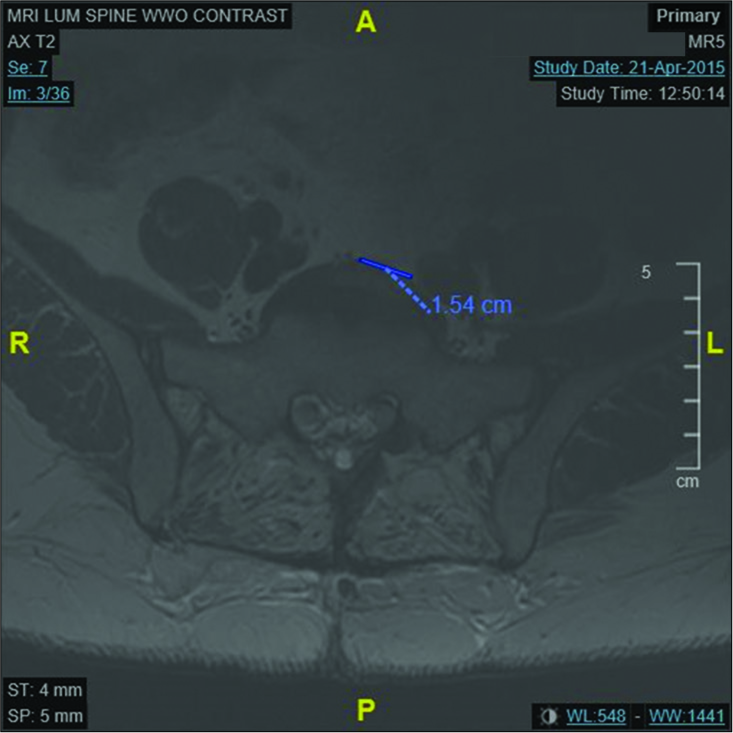

Methods: Lumbar spine MRI from 300 patients was reviewed. The size of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor from L2-S1 was measured. It was defined as the (1) distance between the medial aspect of the aorta and the lateral aspect of the psoas muscle from L2-L5 and (2) the distance between the midpoint of the L5-S1 disc and the medial aspect of the nearest major vessel on the left at L5-S1. In addition, the rostral-caudal location of the iliac bifurcation was measured.

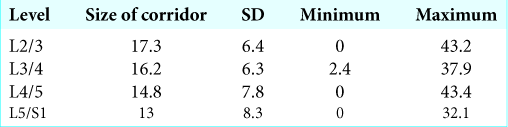

Results: The size of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor at L2/3, L3/4, L4/5, and L5/S1 was, respectively, 17.3 ± 6.4 mm, 16.2 ± 6.3 mm, 14.8 ± 7.8 cm, and 13.0 ± 8.3 mm. The incidence of corridor size n = 158, 52.67%) followed by the L4/5 disc space (n = 74, 24.67%).

Conclusion: The size of the retroperitoneal oblique corridor diminishes in a rostral-caudal direction, often limiting access to the L4/5 and L5/S1 disc spaces.

Keywords: Fusion, Lumbar interbody fusion, Magnetic resonance imaging, Minimally invasive surgical, Oblique lumbar interbody fusion

INTRODUCTION

The objective of this magnetic resonance (MR) morphometric study is to better characterize the oblique corridor between the vasculature and psoas muscle in neurosurgical patients undergoing lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LIF), anterior retroperitoneal transpsoas approach, and oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF). Lateral LIF (LLIF) may be performed through an anterior or posterior approach or minimally invasively.

The anterior retroperitoneal transpsoas approach is another alternative but is associated with an 18% complication rate attributed to plexus injuries, sensory deficits, motor deficits, and anterior thigh pain.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was undertaken with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of our hospital. We retrospectively reviewed 300 consecutive MR imaging (MRI) studies (slice thickness of 3 mm) from 2013 to 2015. The following variables were studied: age, sex, and location of the iliac bifurcation (defined as the first disc or vertebral body where two independent iliac vessels could be discerned on axial imaging) [

Statistical analysis

All MR measurements were taken from axial T2-weighted MR images and reviewed independently by three neurosurgery residents. One-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) to compare the size of the oblique working corridor at L2/3, L3/4, and L4/5 levels was performed.

RESULTS

The 300 patients included 136 men and 164 women, averaging, 63 ± 14.2 years.

Size of oblique working corridor

The size of the oblique working corridor decreased in size from L2/3 to L5/S1. The size of the oblique working corridor at L2/3, L3/4, L4/5, and L5/S1 was 17.3 ± 6.4 mm, 16.2 ± 6.3 mm, 14.8 ± 7.8 cm, and 13.0 ± 8.3 mm, respectively [

Level of aortic bifurcation

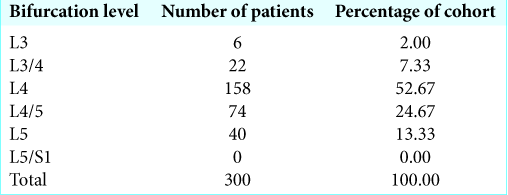

The level of the aortic bifurcation was most commonly found at the L4 vertebral body (158 patients, 52.67%). The second and third most common levels for the aortic bifurcation were the L4/5 intervertebral disc (74 patients, 24.67%) and L5 vertebral body (40 patients, 13.33%) [

Statistical analysis

Utilizing the one-way ANOVA analysis to compare the size of the oblique working corridor, we found a significant difference in the size of the oblique working corridor at P < 0.05 level for each of the three levels (L2-L3, L3-L4, and L4-L5) (F[2, 897] = 10.02, P =0.00005). Post hoc analysis in the form of Tukey honestly significant difference test demonstrated a significant difference in the size of the corridor between L2/3-L4/5 and L3/4-L4/5 at P < 0.05 level. There was no significant difference between L2/3 and L3/4.

DISCUSSION

The LLIF has gained in popularity but is not without its own set of complications, such as 28.5% of patients experiencing hip flexor weakness in one study,[

OLIF has similar benefits to the LLIF without the need to traverse the psoas muscles. Here, the oblique working corridor can be increased in size by sweeping the psoas muscle posteriorly. Woods et al.[

Major complications include vasculature injury due to the more anterior trajectory compared to the LLIF. Woods et al.[

CONCLUSION

The OLIF fusion utilizes a natural corridor that exists between abdominal vasculature and the psoas muscle and avoids the lumbar plexus injuries seen with LLIF. MRI should be utilized to determine the size of the OLIF working corridor and to assess whether LLIF can be safely and effectively performed.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Abel NA, Januszewski J, Vivas AC, Uribe JS. Femoral nerve and lumbar plexus injury after minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach: Electrodiagnostic prognostic indicators and a roadmap to recovery. Neurosurg Rev. 2018. 41: 457-64

2. Chang J, Kim JS, Jo H. Ventral dural injury after oblique lumbar interbody fusion. World Neurosurg. 2017. 98: 881.e1-000

3. Epstein NE. Extreme lateral lumbar interbody fusion: Do the cons outweigh the pros?. Surg Neurol Int. 2016. 7: S692-S700

4. Fujibayashi S, Kawakami N, Asazuma T, Ito M, Mizutani J, Nagashima H. Complications associated with lateral interbody fusion: Nationwide survey of 2998 cases during the first 2 years of its use in Japan. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017. 42: 1478-84

5. Kubota G, Orita S, Umimura T, Takahashi K, Ohtori S. Insidious intraoperative ureteral injury as a complication in oblique lumbar interbody fusion surgery: A case report. BMC Res Notes. 2017. 10: 193-

6. Molinares DM, Davis TT, Fung DA. Retroperitoneal oblique corridor to the L2-S1 intervertebral discs: An MRI study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016. 24: 248-55

7. Salzmann SN, Shue J, Hughes AP. Lateral lumbar interbody fusion-outcomes and complications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017. 10: 539-46

8. Tohmeh AG, Rodgers WB, Peterson MD. Dynamically evoked, discrete-threshold electromyography in the extreme lateral interbody fusion approach. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011. 14: 31-7

9. Woods KR, Billys JB, Hynes RA. Technical description of oblique lateral interbody fusion at L1-L5 (OLIF25) and at L5-S1 (OLIF51) and evaluation of complication and fusion rates. Spine J. 2017. 17: 545-53