- Department of Neurosurgery, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, United States.

- Department of Neurosurgery, Rhode Island Hospital, Rhode Island, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Krissia M. Rivera Perla

Department of Neurosurgery, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_25_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Krissia M. Rivera Perla1, Nathan J. Pertsch1, Owen P. Leary1, Catherine M. Garcia1, Oliver Y. Tang1, Steven A. Toms2, Robert J. Weil3. Outcomes of infratentorial cranial surgery for tumor resection in older patients: An analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. 08-Apr-2021;12:144

How to cite this URL: Krissia M. Rivera Perla1, Nathan J. Pertsch1, Owen P. Leary1, Catherine M. Garcia1, Oliver Y. Tang1, Steven A. Toms2, Robert J. Weil3. Outcomes of infratentorial cranial surgery for tumor resection in older patients: An analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. 08-Apr-2021;12:144. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10699/

Abstract

Background: Poorer outcomes for infratentorial tumor resection have been reported. There is a lack of large multicenter analyses describing infratentorial surgery outcomes in older patients. We characterized outcomes in patients aged ≥65 years undergoing infratentorial cranial surgery.

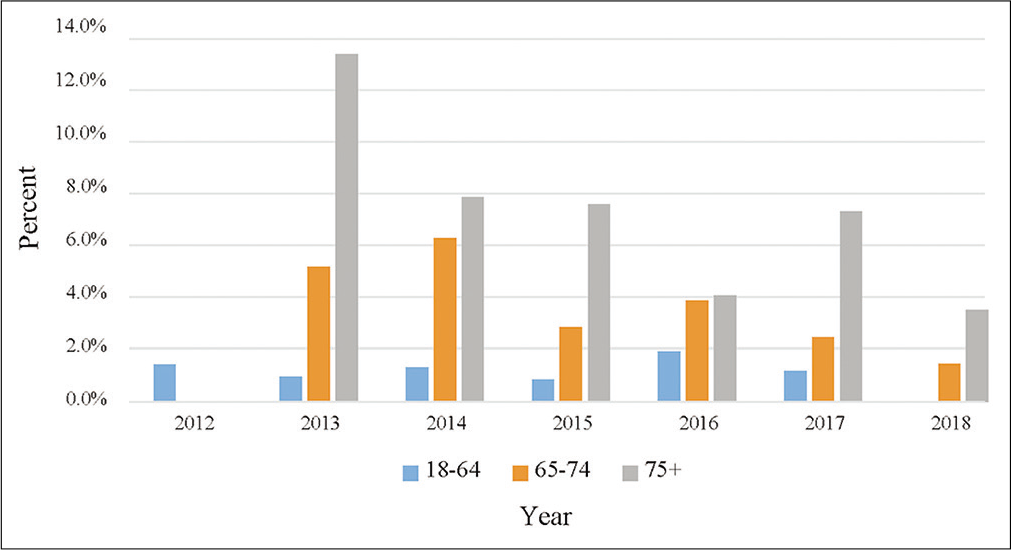

Methods: The National Surgical Quality Improvement Project database was queried from 2012 to 2018 for patients ≥18 years undergoing elective infratentorial cranial surgery for tumor resection. Patients were grouped into 65–74 years, ≥75 years, and 18–64 years cohorts. Multivariable regressions compared outcome measures.

Results: Of 2212 patients, 28.3% were ≥65 years, of whom 24.8% were ≥75 years. Both older subpopulations had worse American Society of Anesthesiologists classification compared to controls (P

Conclusion: Patients ≥65 years experienced more complications, prolonged LOS, and were less often discharged home than adults

Keywords: Brain tumor, Cranial, Elderly, Infratentorial, Meningioma

INTRODUCTION

Central nervous system tumors are associated with high morbidity and mortality and accounted for an estimated 79,718 deaths in the United States between 2012 and 2016.[

Several small, single-institution studies comparing the outcomes of surgical resection for supratentorial and infratentorial brain tumors suggest poorer outcomes in infratentorial neurosurgery; for metastases, elevated risk of local meningeal disease is one reason.[

Although outcomes of infratentorial tumor resection in older populations have been studied, these studies were primarily small, single-center case series; the need remains for large multicenter analyses to compare outcomes for older (>65-years-old) versus younger (<65-years-old) patient populations. We used the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) database to study 30-day postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing infratentorial neurosurgery for definitive resection of intrinsic or metastatic tumors and meningiomas.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

We queried the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Participant Use Data File (ACS-NSQIP PUF; NSQIP) for patients who underwent surgery from 2012 through 2018. NSQIP contains deidentified, prospectively collected inpatient and outpatient multicenter data on demographics, comorbidities, intraoperative variables, and 30-day postoperative outcomes. The Institutional Review Board reviewed the study and deemed it exempt from continuing review (#1466665).

Study population

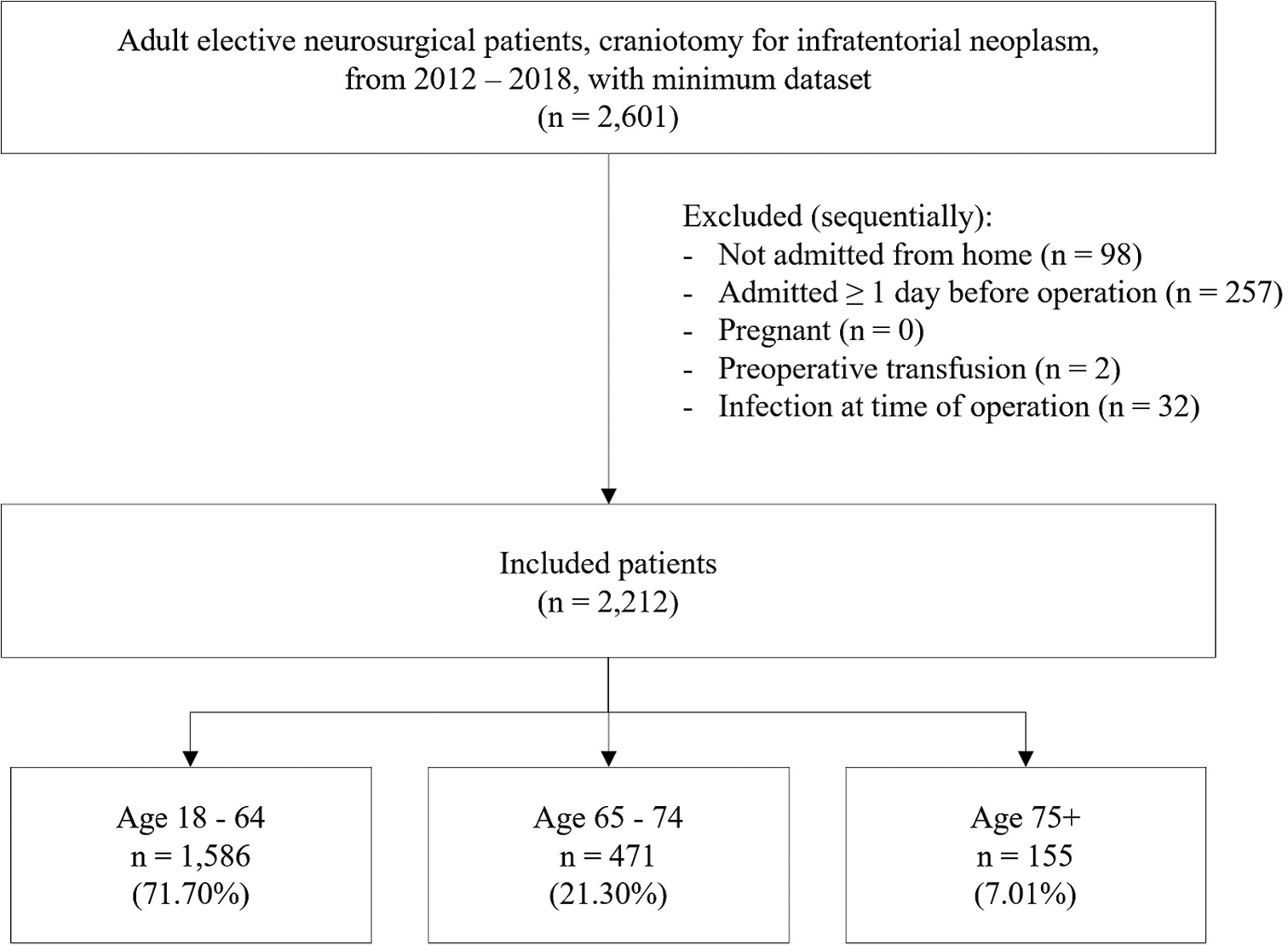

We identified patients aged 18 years or older undergoing elective cranial surgery for infratentorial tumors, including brain metastases, primary intrinsic brain tumors, or meningioma. Cranial surgery patients were selected through a combination of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and postoperative International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes [Supplementary

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System was used to classify patients’ preoperative risk.[

Age categorization

Patients were first grouped into a cohort aged 65 or older and a control cohort aged 18–64 years. As a secondary comparison, the older population was subdivided into those aged 65–74 years and those aged 75 years or older.

Study outcomes

Inpatient and 30-day outcomes were considered. Inpatient outcomes included prolonged length of stay (LOS) and disposition other than home at discharge. Minor and major complications were analyzed during inpatient hospitalization and at 30 days [Supplementary

Statistical methods

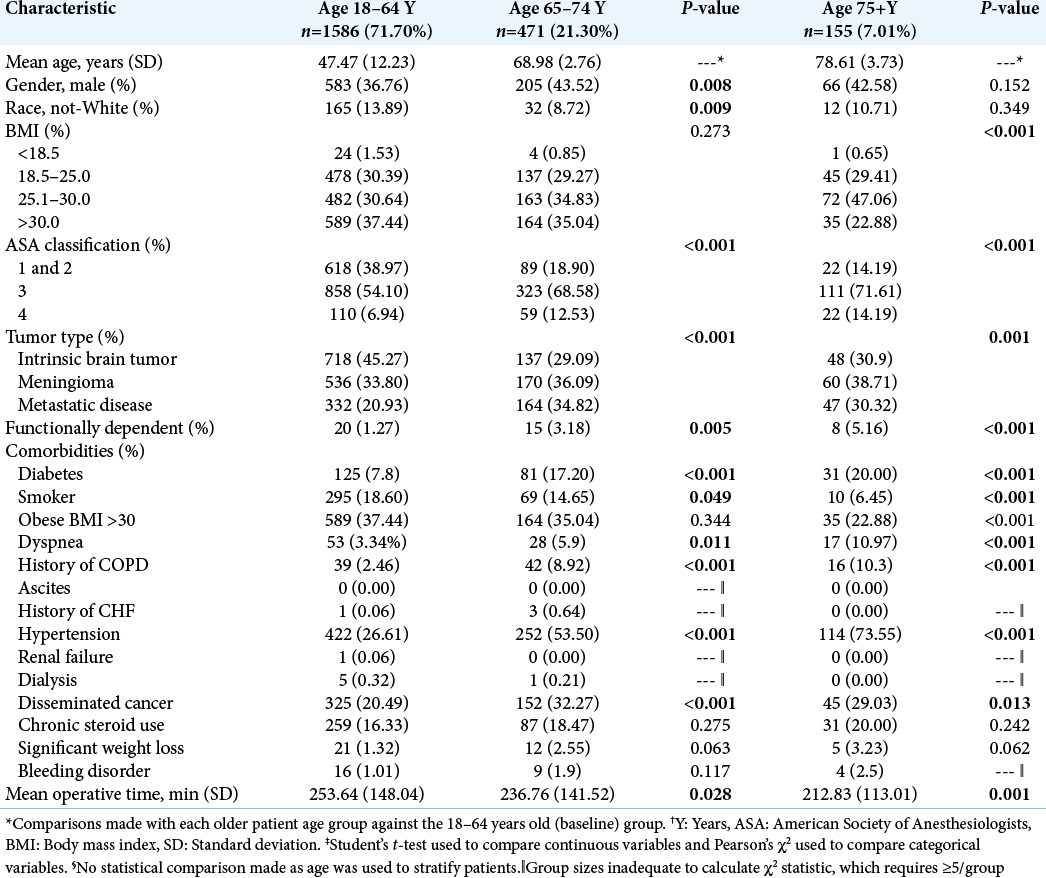

Stata statistical software, version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas), was used for data management and statistical analyses. We compared patient demographics, comorbidities, and intraoperative variables between older and control cohorts using Pearson’s χ2 for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables [

RESULTS

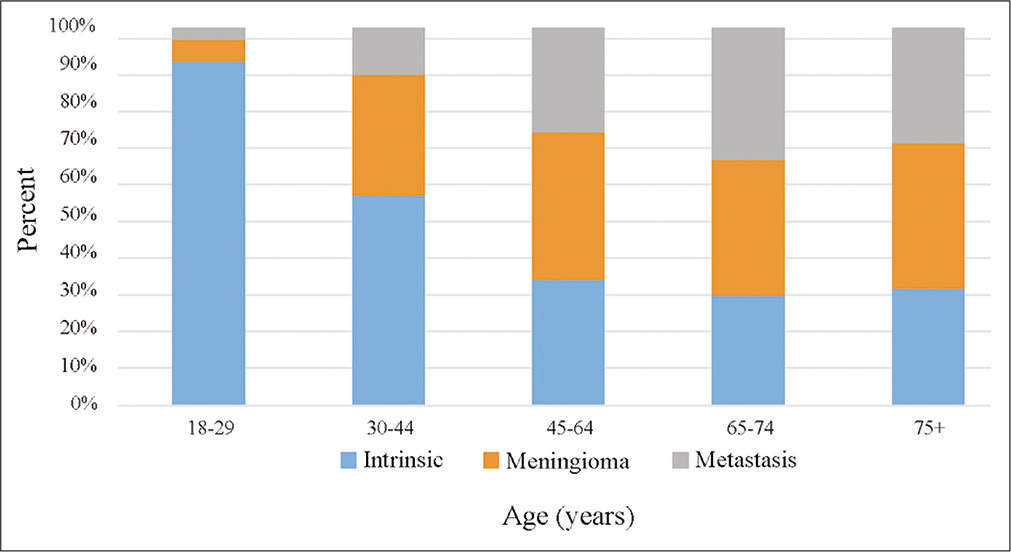

We identified 2212 eligible adult patients who underwent elective craniotomy for infratentorial neoplasm from 2012 through 2018. Of these patients, 28.3% were ≥65 years (n = 626) and, of those patients, 75.2% were aged 65–74 years (n = 471) and 24.8% were aged 75 years or older (n = 155). When comparing each older subpopulation to the control group, patients aged 65–74 years and those aged 75 years or older both had increased distributions of patients in higher ASA categories (both P < 0.001) and were more likely to be functionally dependent compared to the control cohort (65–74 years old, P = 0.029; 75+ years old, P < 0.001). Both older subpopulations were also more likely to have diabetes, dyspnea, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, and disseminated cancer compared to patients 18–65 years. In addition, both older populations had an increased distribution of metastatic disease or meningioma tumor type compared to controls (P < 0.01) [

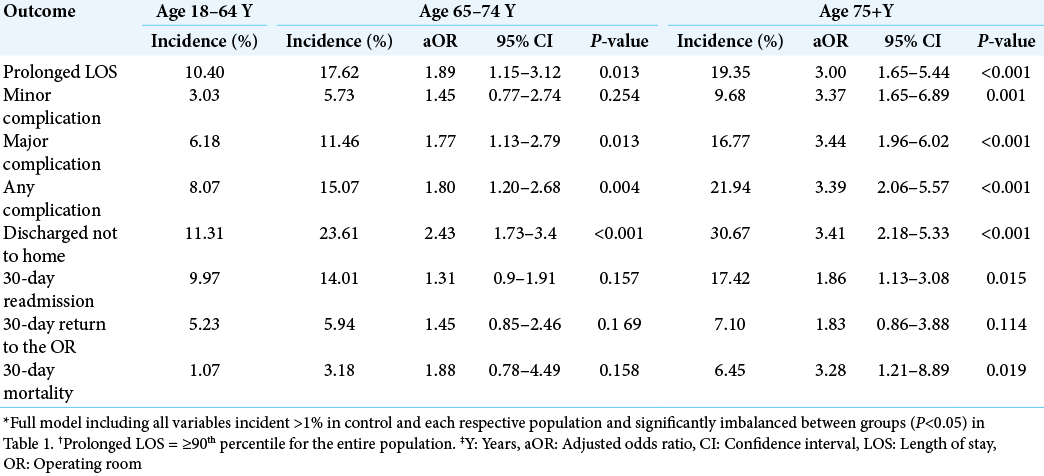

We performed multivariate regression to evaluate the effect of older age (≥65 years), age 65–74 years, and age 75 years or older on outcome measures relative to the control population [

DISCUSSION

This study reinforces and extends prior reports of poorer outcomes in patients undergoing infratentorial tumor neurosurgery.[

From a technical standpoint, one of the most notable differences between performing supratentorial and infratentorial tumor craniotomy is patient positioning during surgery and the proximity of crucial brainstem and cranial nerve structures and functions. While in supratentorial cranial surgery, the patient is typically supine, infratentorial surgery often requires the patient to be in prone or a rotated, lateral position. Prone positioning poses intraoperative challenges in patients with comorbidities such as increasing degrees of elevated BMI and without or with concomitant sleep apnea. Older individuals may not tolerate this position as well as younger or healthier patients; Deiner et al. found patients aged 68 years or older to be twice as likely to experience cerebral desaturation in the prone position compared the supine position, even after adjusting for increased prone surgery duration.[

Our study found patients ≥65 years to be less likely to be discharged to home, more likely to be readmitted within 30 days, and more likely to have died by 30 days compared to those <65 years. These findings present possible opportunities for the use of novel institutional quality improvement initiatives to enhance outcomes for older neurosurgical populations who may be disproportionately affected. Implementing programs such as home health aides and nurse visits for more vulnerable neurosurgical patients may mitigate the number of patients who are unable to be discharged home due to lack of support. In addition, such strategies may reduce the rate of readmissions by ensuring patients receive more structured care. With an aging population in the United States and a looming, disproportionate increase in adults aged ≥65 years through 2030,[

One of the limitations of the present study is the use of a national database with a relatively short (30-day) follow-up period. The absence of detailed, individual demographics, and social determinants of health factors in the NSQIP database further limits study of the effects of factors in the patients’ home, social, and socioeconomic environments that may impact outcomes. Social and economic factors, physical environment, and health behaviors have been shown to account for 40%, 10%, and 30% of an individual’s health outcomes, respectively, while direct clinical care factors (i.e., access and quality of care) cumulatively account for only 20%.[

CONCLUSION

Patients aged 65 years or older experienced higher rates of complications, prolonged LOS, and were less likely to be discharged home compared to the control cohort (aged 64 years or younger). The sub-population of patients aged 75 years or older experienced higher rates of 30-day readmission and mortality compared to the control group, as well. These findings highlight a need for preoperative optimization in older patients undergoing infratentorial tumor cranial surgery and for systems and processes periand postoperatively to enhance support for these patients.