- Department of Surgery, Section of Neurosurgery, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Orlando De Jesus, Department of Surgery, Section of Neurosurgery, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_185_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Annelisse Torres-Urquia, Orlando De Jesus. Golf cart-related neurosurgical injuries. 28-Jun-2024;15:222

How to cite this URL: Annelisse Torres-Urquia, Orlando De Jesus. Golf cart-related neurosurgical injuries. 28-Jun-2024;15:222. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/12965/

Abstract

Background: Head and spine injuries sustained following golf cart accidents have been rarely analyzed. This study aimed to describe a series of patients sustaining golf cart injuries requiring neurosurgical management for head or spine injuries.

Methods: The University of Puerto Rico Neurosurgery database was used to retrospectively identify and investigate patients who sustained a golf cart-related injury requiring a neurosurgical evaluation during 15 years.

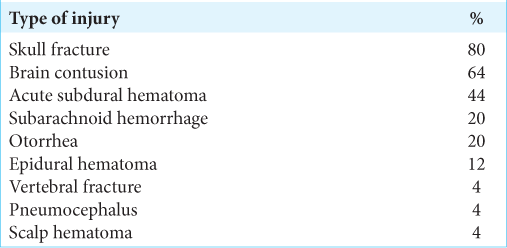

Results: The analysis identified 25 patients with golf cart-related injuries requiring neurosurgical management with a median age of 16 (interquartile range 13–34). Seventeen patients (68%) were female. The primary mechanism of injury was ejection from the cart in 84% of the patients (n = 21). The most frequent head injury was a skull fracture in 80% of patients (n = 20). Intracranial hemorrhage was present in 76% of patients (n = 19), with brain contusions (n = 16, 64%) being the most common. Eighteen patients (72%) were admitted for surgery or neurological monitoring. The median hospital length of stay among hospitalized patients was 5.5 days. Ten patients (40%) were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a median stay of 8.5 days. Four patients (16%) required surgery for their injuries. At discharge, 80% of patients (n = 20) had a good outcome.

Conclusion: This study showed that children and adolescents are at high risk for golf cart-related neurosurgical injuries. This form of transportation can produce considerable neurological injuries, the primary mechanism of injury being ejection from the cart. Approximately three-quarters of the patients need hospital admission, with half requiring an ICU stay.

Keywords: Golf cart, Neurosurgery, Pediatric, Traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

The use of golf carts has expanded in the past decades from its classic use on golf courses to an everyday mode of transportation in resorts, gated communities, and even open roads. This augmented use has increased the incidence of golf cart-related injuries.[

Head and spine injuries sustained by golf cart accidents are usually underreported, as only patients requiring management at an emergency department (ED) are included in the reports. This study aimed to describe and analyze a series of patients sustaining golf cart injuries requiring neurosurgical management for head or spine injuries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The University of Puerto Rico Neurosurgery database, which has been stored daily in Excel software since 2004, was used to identify patients who sustained a golf cart-related injury requiring a neurosurgical evaluation during 15 years from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2023. The database was queried in August 2023 to retrieve information for the study. All patients who sustained a golf cart-related injury requiring a neurosurgical evaluation were included in the study. No patients were excluded from the study. For each identified patient, basic demographics were collected, including age and gender. In addition, the following variables were investigated: mechanism of injury (ejection, rollover, and pedestrian), injuries received, Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score at arrival, days of hospitalization, days at the intensive care unit (ICU), surgery performed, and outcome on discharge using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) score. A good outcome was defined as a mRS score of 0–3. Descriptive statistics were used to report frequency, median value, and interquartile range (IQR). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the participating institution (protocol 2308131225). Due to the study’s retrospective nature, informed consent was not required.

RESULTS

The retrospective analysis identified 25 patients with golf cart-related injuries requiring neurosurgical management during the 15 years from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2023. Their ages ranged from 4 to 69, with a median age of 16 (IQR = 13–34) [

Eighteen patients (72%) were admitted for surgery or neurological monitoring, while 7 (28%) were discharged from the ED after being observed for 1 day. The median hospital length of stay among admitted patients was 5.5 days (IQR 3–16; range 2–40). Ten patients (40%) were admitted to the ICU with a median stay of 8.5 days (IQR 4–14; range 1–23). Four patients (16%) required surgery for their injuries. Among them, two had a decompressive craniectomy and were readmitted a few months later for a cranioplasty. At discharge, 80% of patients (n = 20) had a good outcome. Among the patients with poor outcomes, one died. Surgery was not performed on this patient due to the catastrophic nature of the injuries on arrival.

Three patients (12%) returned to the ED for reevaluation. One patient showed worsening symptoms and required surgery for an expanding subacute subdural hematoma. The other two patients developed post-traumatic seizures that were controlled with oral medications at the ED and did not require admission. One of the patients experienced seizures 1 week after discharge, while the other experienced them 3 months later.

DISCUSSION

Most golf cart accidents occur on golf courses; however, some occur in resorts, residential areas, or farms.[

Recently, Horvath et al. documented an increase in head and neck injuries after a golf cart accident, demonstrating that they were the most frequent body location for injuries.[

Simpson et al. found that most patients with a golf cart-related injury sustained mild TBIs with good outcomes, which they ascribe to the low speed of the cart.[

In their analysis, Simpson et al. reported that 87% of patients had a good outcome at discharge.[

The incidence of golf cart accidents in Puerto Rico is unknown as no investigations have been previously done. These accidents do not have to be reported to the police or the transportation department. Contrasting the results of golf-cart accidents noted in our cohort with comparable accident-type scenarios in which a cabin does not protect, the occupant may provide helpful information. However, few reports exist in Puerto Rico of comparable transport such as an all-terrain vehicle (ATV), motorcycle, or bicycle. In the study by Acosta and Rodriguez, motorcycle accidents occurred twice as frequently as ATV accidents.[

Individuals must develop more awareness of the injuries that can be sustained while riding golf carts. Community safety guidelines must be implemented to reduce the incidence of these injuries. Several authors have suggested rigorous safety regulations during golf cart driving, including a stricter minimum legal age for adolescents or children operating the cart to reduce the number of inexperienced operators.[

In our study, a substantial number of injuries occurred in children; for this reason, we agree with the previous authors’ recommendations. Golf carts are not prepared for the secure transportation of children, and their use for transporting children should be dissuaded. Children and adolescents without a driver’s license should not operate a golf cart. Adult drivers transporting children should operate golf carts at low speeds, braking slowly and avoiding sharp turns to reduce the risk of passenger ejection. The use of rear-facing cart seats should be banned in children and adolescents as they are associated with high rates of passenger ejection. Golf carts used for transportation in resorts, gated communities, and open roads should include seat belt safety equipment as they effectively reduce ejection from the cart.

Limitations

This study contains several limitations. First, the study design was retrospective and observational, which may be subject to bias or errors. Second, the institution where the study was performed is a trauma level I hospital; therefore, only those cases with major trauma involving a golf cart accident were referred to. Finally, the study involved the population of Puerto Rico, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or countries where golf cart use varies and may impact the incidence of golf cart accidents.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that children and adolescents in our population are at high risk for golf cart-related neurosurgical injuries. This form of transportation can produce considerable neurological injuries, the primary mechanism of injury being ejection from the cart. Approximately three-quarters of the patients need hospital admission, with half requiring an ICU stay. However, the outcome in most patients is good.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, number 2308131225, dated August 31, 2023.

Declaration of patient consent

Patients’ consent not required as patients’ identities were not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Acosta JA, Rodríguez P. Morbidity associated with four-wheel all-terrain vehicles and comparison with that of motorcycles. J Trauma. 2003. 55: 282-4

2. Gibson K, Stevens TJ, Krause MA. Adult golf cart injuries: A rising hazard off the course. Traffic Inj Prev. 2023. 24: 352-5

3. Horvath KZ, McAdams RJ, Roberts KJ, Zhu M, McKenzie LB. Fun ride or risky transport: Golf cart-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments from 2007 through 2017. J Safety Res. 2020. 75: 1-7

4. McGwin G, Zoghby JT, Griffin R, Rue LW. Incidence of golf cart-related injury in the United States. J Trauma. 2008. 64: 1562-6

5. Miller B, Yelverton E, Monico J, Replogle W, Jordan JR. Pediatric head and neck injuries due to golf cart trauma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016. 88: 38-41

6. Passaro KT, Cole TB, Morris PD, Matthews DL, MacKenzie WR. Golf cart related injuries in a North Carolina island community, 1992-4. Inj Prev. 1996. 2: 124-5

7. Rahimi SY, Singh H, Yeh DJ, Shaver EG, Flannery AM, Lee MR. Golf-associated head injury in the pediatric population: A common sports injury. J Neurosurg. 2005. 102: 163-6

8. Simpson B, Shepard S, Kitagawa R. Golf cart associated traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019. 33: 1476-8

9. Smith RA, Ling S, Alexander FW. Golf related head injuries in children. BMJ. 1991. 302: 1505-6

10. Starnes JR, Unni P, Fathy CA, Harms KA, Payne SR, Chung DH. Characterization of pediatric golf cart injuries to guide injury prevention efforts. Am J Emerg Med. 2018. 36: 1049-52

11. Tracy BM, Miller K, Thompson A, Cooke-Barber J, Bloodworth P, Clayton E. Pediatric golf cart trauma: Not par for the course. J Pediatr Surg. 2020. 55: 451-5

12. Watson DS, Mehan TJ, Smith GA, McKenzie LB. Golf cart-related injuries in the U.S.. Am J Prev Med. 2008. 35: 55-9