- Department of Neurosurgery, Neurosurgery Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Al-Nahrain, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq

- Department of Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Al-Iraqia, Baghdad, Iraq,

- Department of Neurosurgery, Azerbaijan Medical University, Baku, Azerbaijan

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States.

Correspondence Address:

Samer S. Hoz, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_966_2022

Copyright: © 2023 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Ismail M1, AbdulWahid J2, Al-Zaidy MF3, Al-Khafaji AO3, Albairmani SS4, Abdulsada AM5, Salih HR1, Hoz SS6. Neurosurgery theater-based learning: Etiquette and preparation tips for medical students. Surg Neurol Int 28-Apr-2023;14:153

How to cite this URL: Ismail M1, AbdulWahid J2, Al-Zaidy MF3, Al-Khafaji AO3, Albairmani SS4, Abdulsada AM5, Salih HR1, Hoz SS6. Neurosurgery theater-based learning: Etiquette and preparation tips for medical students. Surg Neurol Int 28-Apr-2023;14:153. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12298

Dear Editor,

INTRODUCTION

Early surgical exposure increases the understanding of neurosurgery and affects the interest in neurosurgery as a career.[

As an outline for expected behavior, students can use these steps to reflect good orientation while also giving them the advantage of being involved as part of the surgical team.

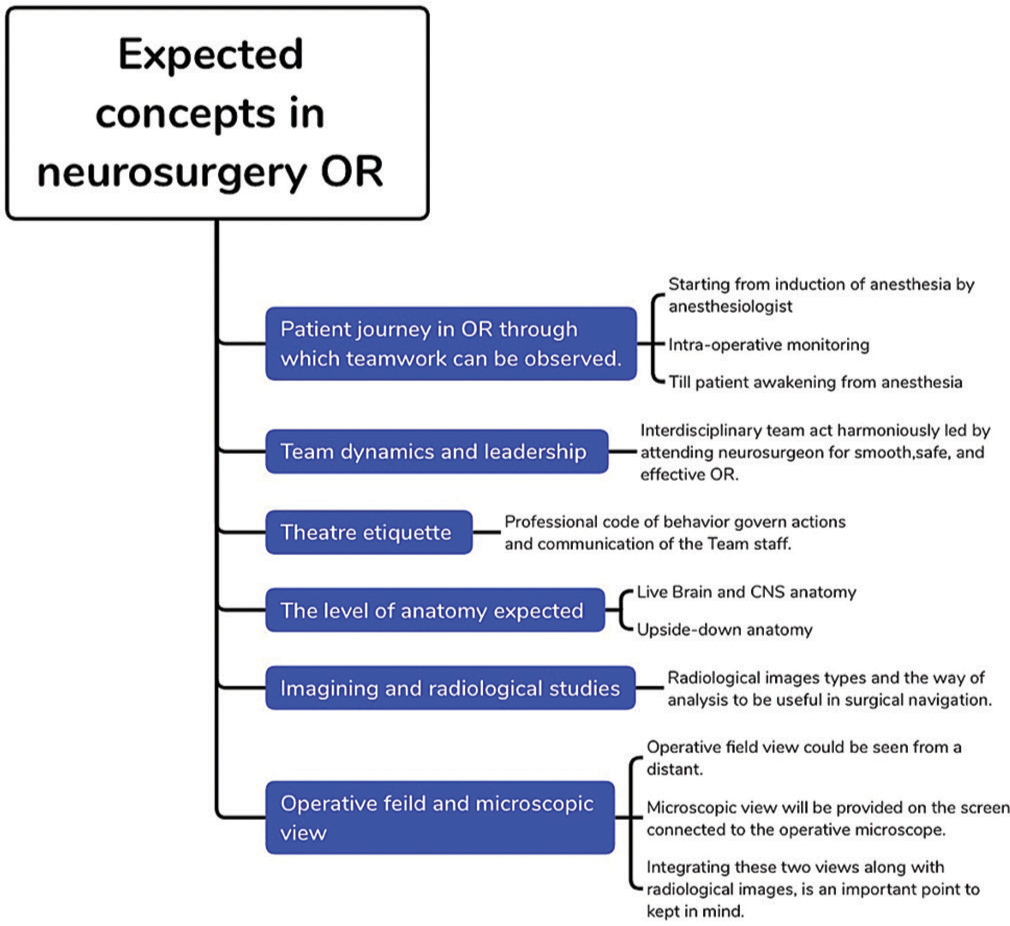

DESCRIBING NEUROSURGERY OR

Neurosurgery OR is a place where the unexpected happens. It involves an interdisciplinary dance, in which different attending surgeons, residents, anesthetic teams, and nurses collaborate to achieve one shared goal; patient safety. A medical student will notice the leader concept, how the neurosurgeon acts in the OR, the team structure, and the communication that makes OR safe and effective for the neurosurgical patient who will undergo irreversible interventions and neurological scarifications.[

Although the neurosurgical operating theater can be an intimidating environment for the medical student, it can also provide a wealth of learning opportunities.[

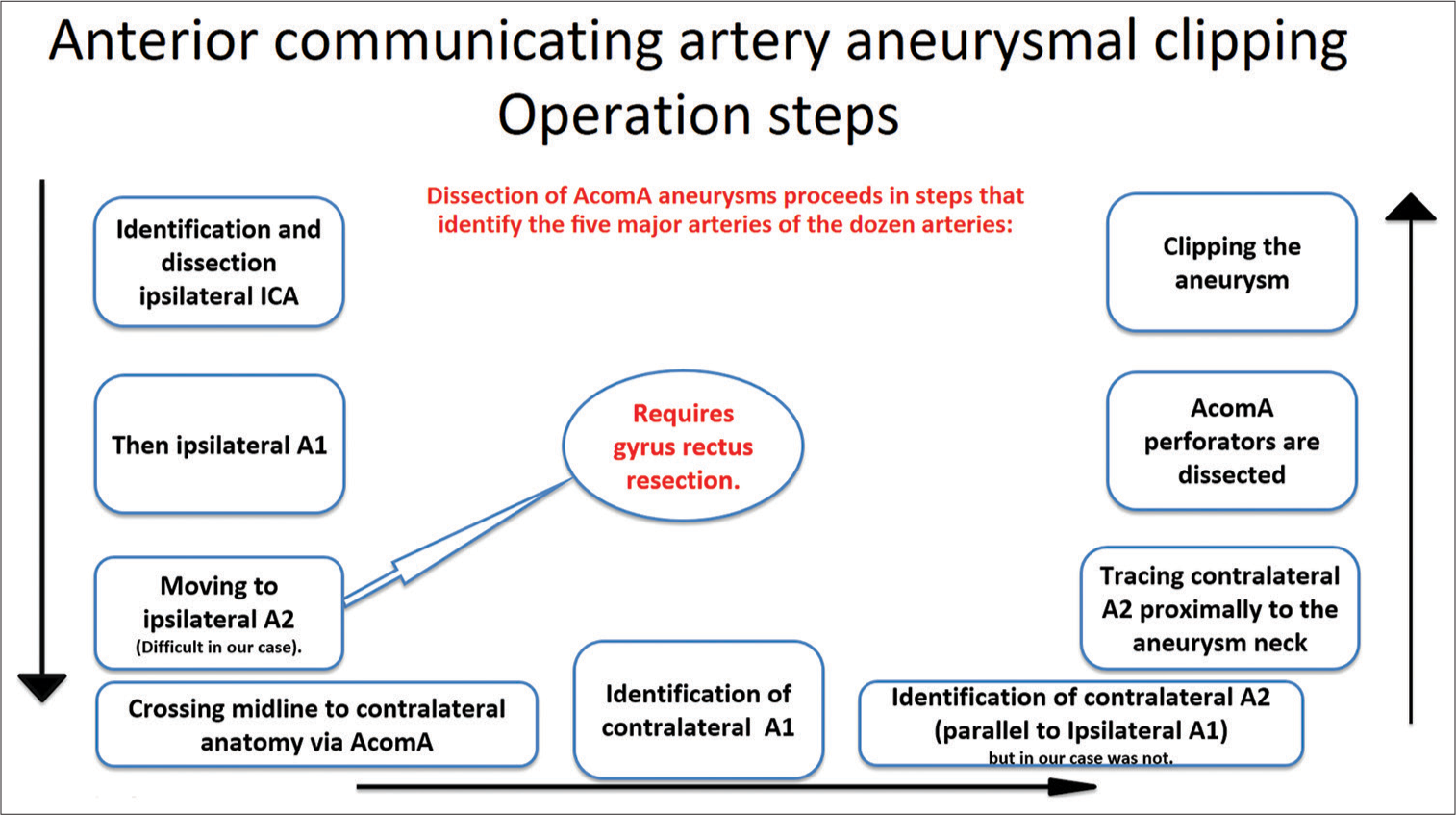

Let us take a journey to learn the etiquette and preparations for the 1st time attending a neurosurgery operation; it is summarized in [

THE DAY BEFORE THE OPERATION

Having in mind that after the end of the surgery, the main events, steps of surgery, and lessons learned from this experience, should all be documented and preserved in any way like writing or even making a video would be an excellent start to make one work hard to be prepared in a small amount of time in the day before surgery. Knowing the brief history and examination findings of the case, initial radiological images, and the name along with the time and place of the surgery, if requested politely by the surgeon or the resident, justified by the need to explore and learn about the surgery. Asking about details should be avoided here; take the case and start to learn on your own.

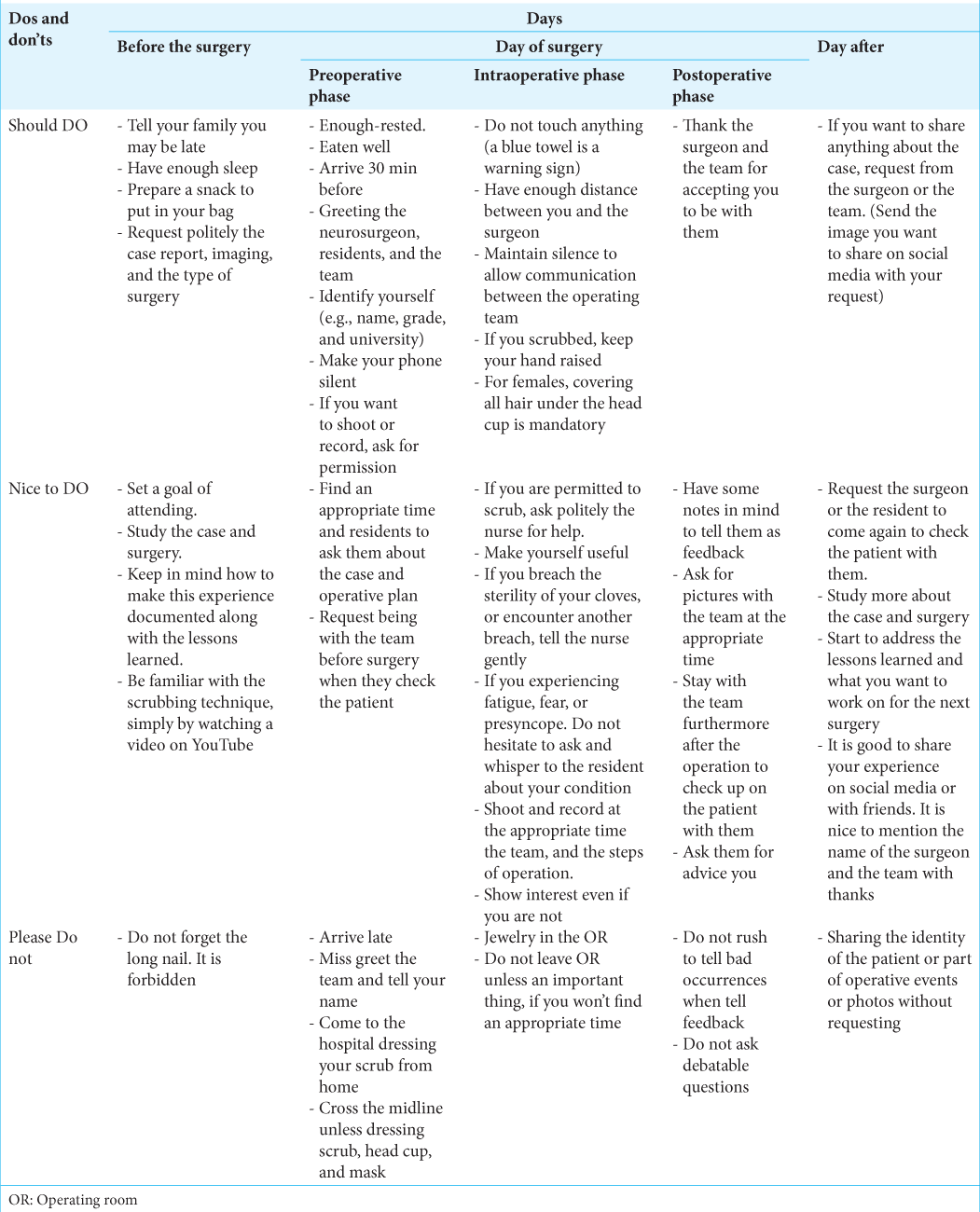

The resident sent you this: 54-year-old female presented with brief loss of consciousness, followed by meningismus, no weakness, and GCS 15), the radiological image of computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography are shown in [

Figure 2:

(a) Brain computed tomography, axial section shows diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage in the basal cistern right sylvian, interhemispheric, ambient, and thickest in the anterior hemispheric fissure (Yellow arrows).(b) Anterior view computed tomography angiography shows an anteriorly projecting saccular “anterior communicating artery” aneurysm (Yellow arrow).

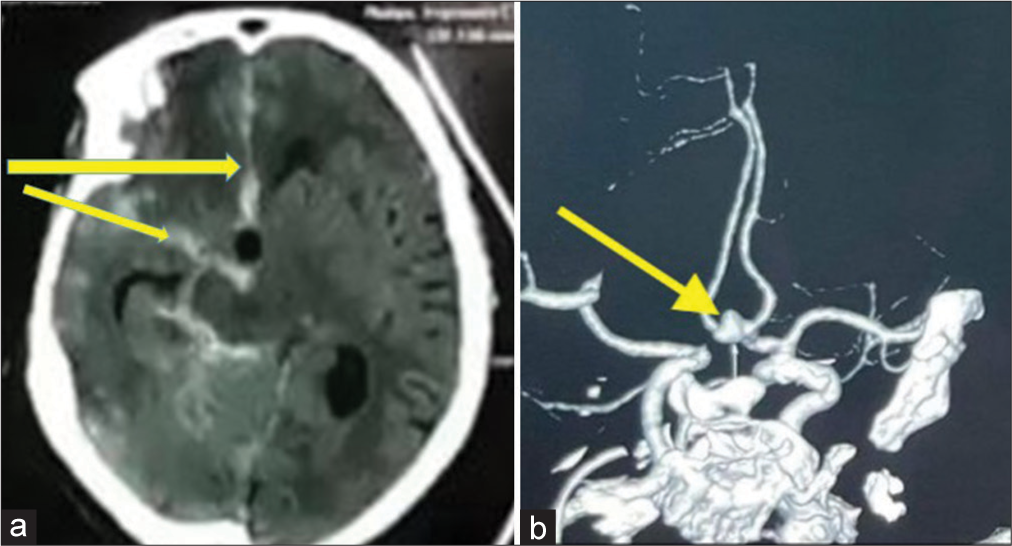

To understand the case, start with anatomical orientation. Understand the pathology and its location (aneurysm projecting anteriorly from anterior communicating artery [AcomA] in our case), and then study the surgery steps to prepare yourself to benefit from the experience scientifically. To study anatomical relations to the surgery, we suggest starting with a simple online image search to go from the schematic representation of anatomy to the cadaveric and then operative surgical view. The next step would be a neurosurgical atlas to gain a deeper understanding of anatomy. Radiopedia can also benefit you, helping you grasp the radiological anatomy of the case. As an example, start by searching for the “Circle of Willis” and “Anterior communicating artery (AcomA)” schematic and cadaveric on Google images. Then search for AcomA aneurysm schematic and operative. Make sure to write the lesion site while searching to understand better the surgery you will attend. After that, search for the steps of surgery, you can use Google scholar to read an article describing the steps or look them up on websites like the Neurosurgical Atlas. It is summarized in the schematic representation [

Figure 3:

Schematic presentation of the anterior communicating artery aneurysm clipping operation steps. (AcomA: Anterior communicating artery, ICA: Internal carotid artery).[

Considering some concepts like these, you are a student to listen and learn, not speak a lot mainly. Even theoretically, how to dress appropriately (scrubs, caps) and wash hands is also beneficial. Please remember that long nails are forbidden. Prepare your scrub and slipper; please remember do not come dressing scrub from home. The last thing to put in mind on this day is to have good rest and enough sleep before the next day, which might be long. So be prepared for long hours, and tell your family you may be back late. Take in your backpack a piece of snack. It will save you as you never know how long the procedure will last and when you will get a chance to eat. This is neurosurgery OR!

ON THE DAY OF THE SURGERY

Preoperative phase

You should have well rested, eating, and arriving on time 15–30 min before the operation. Greeting the surgeon and the team, along with introducing yourself (name, medical school, and school year at least), is an essential social point.

It is an excellent time to ask the resident or nurses to figure out the rules: If you do not ask, then the rules are never really explained to you, and you may be in trouble when you break them. If you are not familiar with the case, find the appropriate time, but do not if you see the residents and attending surgeons are busy. Ask them about the case to be illustrated briefly, along with the operative plan.

It is good, and actually will give a good impression on you, to ask the attending surgeon or residents to be with them when encountering the patient before bringing him/her to the OR to observe the process of assurance, evaluation, and taking them through the consent form.

Please remember not to cross the red line unless wearing your head cover, masks, and scrubs in the dressing room, do not bring your bag, computer, and iPad to OR. You can eat your snack before entering OR. And please remember to keep your phones on silent. If you want to record during the operation, it is a good time to have permission from the attending surgeon and the team. Avoidance of jewelry in the OR should be considered.

Intraoperative phase

Neurosurgery is a complex specialty: in addition, neurosurgery OR means multiple individuals of an interdisciplinary team, sterile theater, operative microscope, drill sets, and various sophisticated machines and monitors surrounding the operating table within a relatively small-sized room. All should be kept in mind when you are there. As you enter the neurosurgery ORs be careful not to touch anything. A peculiar thing to consider is the sterile theater; it affects patient safety and should be on top when in OR observing the operation. If not scrubbed in, recognize the sterile field and how to avoid it. Remember to stay away from the sterile field. Any blue towel or covering should raise red flags in your mind.

Keep quiet enough not to disturb the operating staff ’s communication. It is best not to take part in discussions unless you have been invited and there is an opportunity to speak. You will be encouraged to ask questions, but please do so when the atmosphere is calm. Always find the appropriate timing.[

Furthermore, it is better not to use the phone in the operating theater unless you need to record part of the surgery. Please do not take a personal photo of the staff unless you take their permission. Try to be useful in OR; if you are not scrubbed in, find yourself a role. Find a job you can do, like recording information (e.g., write down the incision and closing times). In our case, “AcomA aneurysm” we were asked to record the time for temporary clipping as it was applied before the permanent one. Try to be the last one to exit from the OR to have the full experience, even the part of the patient awakening from anesthesia after requesting from the surgeon and anesthesiologist, “Can I stay to observe?”. Try to look interested even when you’re not. It is part of showing thanks to the team.

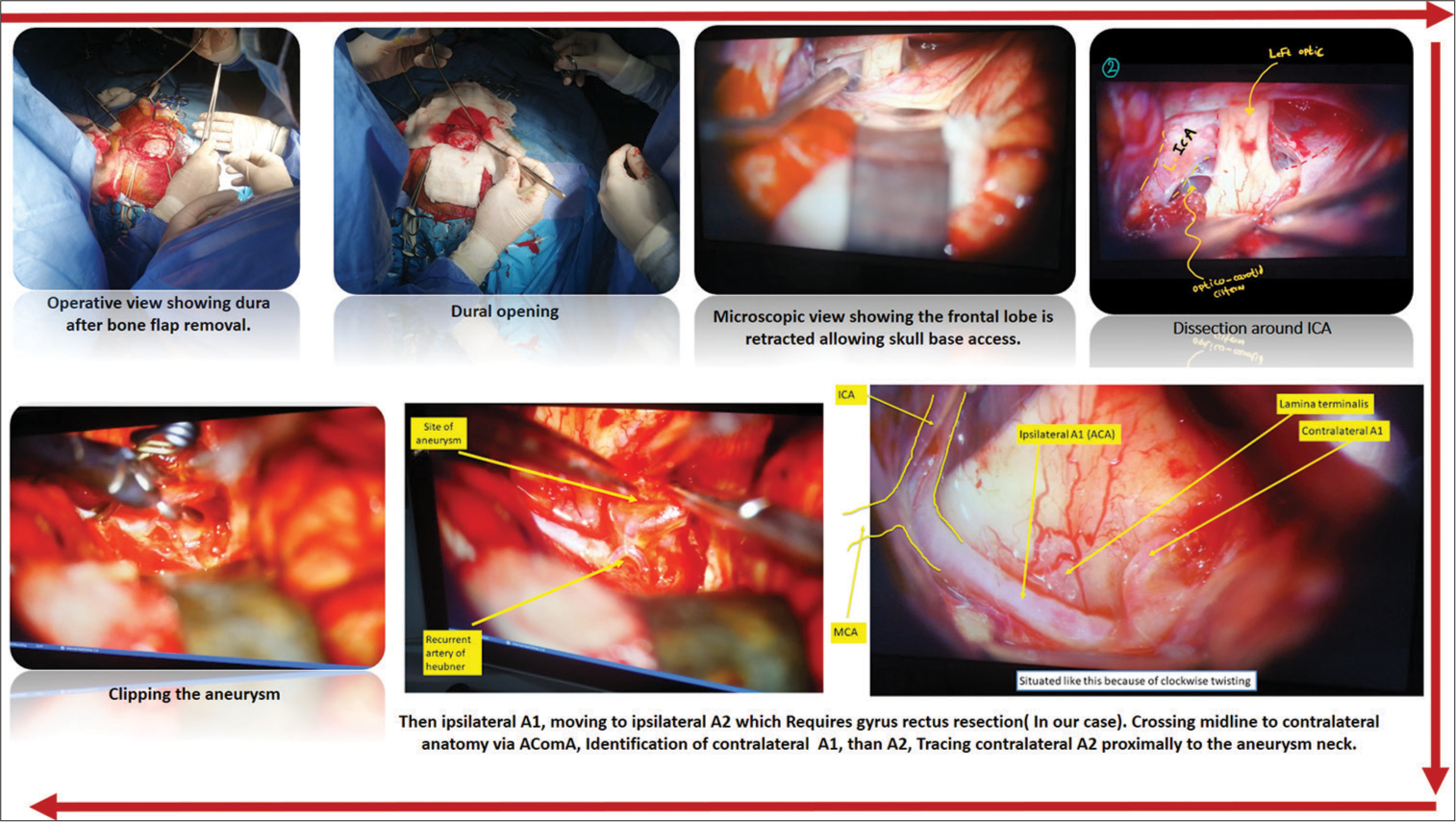

Most neurosurgery OR provide video screens in the OR for monitoring surgeries as most neurosurgical operations are conducted under a microscope. You do not have to be scrubbed to observe a case. Make sure to notice the positioning of the patient’s body, head, and the site of craniotomy, as this will make a huge difference when you try to imagine and understand the surgery. We recommend taking photos and recording from the screen as well. Hence, you can later arrange the operation steps in a way like in [

The view under the microscope is far superior; if you have the opportunity to scrub, this would be a tremendous advantage to watch the field from different perspectives and compare them.

Scrubbing

When you get the opportunity to scrub in, you may have trouble dressing the gown; politely ask the nurse to help you. In general, the scrubbing technique is the same, although you may see neurosurgeons put double gloving. Even if you are scrubbed in and sterile, do not touch anything, especially the surgical field. When scrubbed, get close to the surgeon and the field and try not to move a lot not to affect the surgeon’s position, as neurosurgery is done in small corridors between vital brain structures. Any disturbance or unexpected movements can be dangerous.[

We suggest keeping this in mind and taking advantage of scrubbing by looking at the lesion’s operative field and surgical corridor to correlate it with the microscopic view on the operative screen for a better understanding of the surgery and how the neurosurgeon operates.

There will be some questions for you, particularly the anatomical one. Please do not jump to answer questions immediately; it is not a race. If you know, tell; otherwise, say I do not know.

If you are requested to assist during a case, mostly your role might be holding the sucker or participating in irrigation. You might have a chance to do a few stitches when closing the patient up. In general, Do just what is required from you, and do not anticipate surgical stages. If you do not understand or feel like you are not up to the task, do not hesitate to ask for help.

Although it is improper to quit while surgery is on if you need to go, do not declare it. If you have not been scrubbed, ask one of the residents for permission to exit. If you are scrubbed and need to leave, you must pick an opportune moment and obtain permission from the senior surgeon.

Presyncope and syncope have previously been recorded in the OR and are prevalent among students entering the OR for the 1st time.[

Postoperative phase

Make sure while in operation to have some notes in mind and address what you find unique to your experience, whether scientifically or even feelings about your first experience in neurosurgery OR. The latter is preferable feedback delivered to the team and neurosurgeon. Start with the positive thing that affects you and what you have learned. For example, “it was an interesting experience; I did not imagine neurosurgery to be like this, I see how good the teamwork is and how you act in harmony, all targeting the patient safety, thank you for accepting me to be part of your work today.” Then go to the bad thing but try to use appropriate words and ways to be delivered well like “I wish I could participate, or do that thing” which makes a real difference. If you have questions, make sure not to make them debatable, and try not to ask deep scientific questions. Ask them for advice to be prepared better next time. Ask them to have a picture with them and the possibility of sharing it on social media.

It is better to stay with the team when they check the patient after the surgery, but it is not mandatory. Before leaving, thank everyone from the surgeon, nurses, residents, and anesthesiologists. This will give the team an overall good impression of you.

THE DAY AFTER THE OPERATION

To have the entire patient journey experience, you can request the resident to come and check the patients with them or even ask them if the patient’s condition has improved or not. Try to have this experience documented, write the lessons you have learned and the suggestions that were delivered to you, study more about the case and the surgery you have been in, and prepare a document or film from the videos and photos you have recorded. In [

It is good to share your experience on social media and thank the team for their time and work and for hosting you. Never share any patient-identifying information like name or face, and do not share any part of the surgery unless you take permission from the surgeon.

DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR OF MEDICAL STUDENTS

Arriving lately, do not show respect to the surgeon and the team, laughing in front of patients when it is not the appropriate time, Yelling in OR, talking and whispering, touching the sterile, moving haphazardly, being too close to the surgeon and affecting his position. Not showing interest. Not showing thanks to the team for accepting their presence or showing only bad things when giving feedback about the operations. Sharing the identity of the patient or part of the procedure without permission from the surgeon.

CONCLUSION

The overall experience of neurosurgical theater-based learning is positive, as the surgical exposure intervention increased the understanding of neurosurgery and affected the interest in neurosurgery as a career. Based on our experience, in this article, we provided some potential considerable preparations and etiquette to medical students that, if kept in mind, will reflect good orientation. Better preparation, such as reading up on the case and operation, an introduction to theater etiquette, how to act, and what to say, would improve the learning experience.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Bhattarai R, Chen C, Liang CF, Huang TC, Wang H, Ling C. The surgical approach for clipping anterior communicating artery Aneurysm. Nep J Neurosci. 2019. 16: 10-2

2. Bowrey DJ, Kidd JM. How do early emotional experiences in the operating theatre influence medical student learning in this environment?. Teach Learn Med. 2014. 26: 113-20

3. Courtenay M, Nancarrow S, Dawson D. Interprofessional teamwork in the trauma setting: A scoping review. Hum Resour Health. 2013. 11: 57

4. Ehlers AP, Wright AS, Palazzo F, editors. Fundamentals of acceptable behavior in the operating room (Etiquette). Fundamentals of General Surgery. Cham: Springer; 2018. p.

5. Esterl RM, Henzi DL, Cohn SM. Senior medical student “boot camp”: Can result in increased self-confidence before starting surgery internships. Curr Surg. 2006. 63: 264-8

6. Flannery T, Gormley G. Evaluation of the contribution of theatre attendance to medical undergraduate neuroscience teaching--a pilot study. Br J Neurosurg. 2014. 28: 680-4

7. Ford PJ. Vulnerable brains: Research ethics and neurosurgical patients. J Law Med Ethics. 2009. 37: 73-82

8. Larsen T, Beier-Holgersen R, Østergaard D, Dieckmann P. Training residents to lead emergency teams: A qualitative review of barriers, challenges, and learning goals. Heliyon. 2018. 4: e01037

9. Morzycki A, Hudson A, Williams J. Medical student presyncope and syncope in the operating room: A mixed methods analysis. J Surg Educ. 2016. 73: 1004-13

10. Shamim MS, Sobani ZA. Neurosurgical electives: Operating room survival guide. World Neurosurg. 2012. 78: 18-9

11. Zuccato J, Kulkarni A. The impact of early medical school surgical exposure on interest in neurosurgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2016. 43: 410-6