- Department of Neurosurgery, Puerta de Hierro University Hospital, Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_392_2019

Copyright: © 2019 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Ruth Prieto, Celia Ortega. Parafalcine subdural empyema: The unresolved controversy over the need for surgical treatment. 18-Oct-2019;10:203

How to cite this URL: Ruth Prieto, Celia Ortega. Parafalcine subdural empyema: The unresolved controversy over the need for surgical treatment. 18-Oct-2019;10:203. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9712/

Abstract

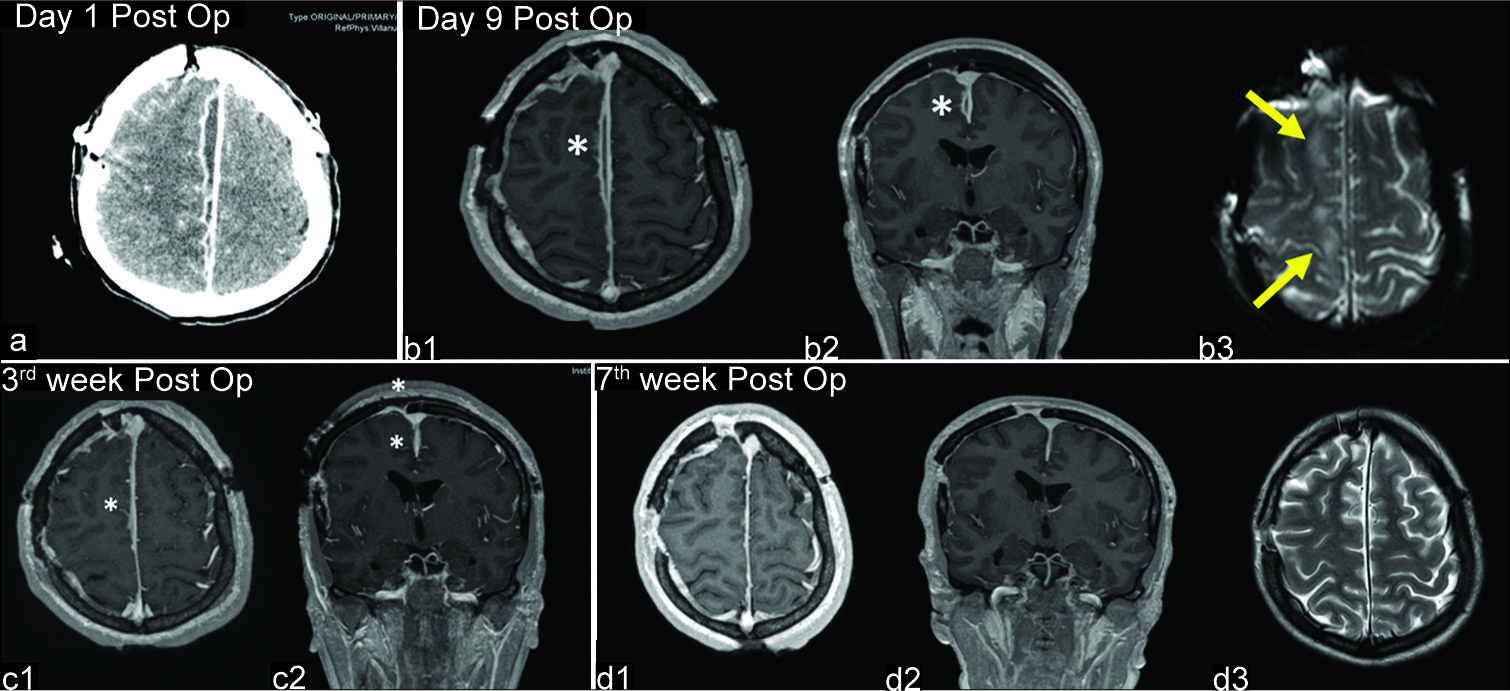

Background: Parafalcine subdural empyema (SDE) is a rare entity consisting of pus accumulating below the longitudinal sinus, between the falx cerebri and the arachnoid layer covering the medial surface of the cerebral hemisphere. Its treatment strategy is controversial, but most clinicians have the general belief that appropriate treatment consists of prompt surgery combined with long-term antibiotic therapy. Nevertheless, six reports published in the 1980s provided evidence that antibiotic therapy alone is a safe and suitable option. The treatment strategies and outcomes of the 31 well-described cases previously published, in addition to our own, are discussed.

Case Description: We report a 21-year-old female with a right-side parafalcine SDE who presented with fever, headache, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and contralateral hemiparesis 3 weeks after undergoing sinonasal surgery. Despite clinical symptoms almost entirely abating after starting treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, magnetic resonance imaging performed during the 2nd and 3rd weeks showed progressive enlargement of the interhemispheric collection (from 4 cm3 to 30 cm3). We reflect on the treatment strategy chosen for this patient, who experienced a total recovery.

Conclusion: A nonsurgical strategy for parafalcine SDE might be contemplated for patients with a good clinical condition and no major midline shift on neuroradiological studies, given their usual indolent course and the relative difficulty in reaching the interhemispheric fissure. Conversely, surgery should be contemplated when the collection significantly enlarges despite antibiotic therapy. When surgical drainage is added to antibiotics, broad- range 16S ribosomal DNA polymerase chain reaction of the empyema is recommended to identify the causative organism as pus cultures are usually sterile.

Keywords: 16S ribosomal DNA polymerase chain reaction, Antibiotic therapy, Interhemispheric empyema, Parafalcine subdural empyema, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Subdural empyema (SDE) is a rare but potentially life-threatening disease consisting of a pyogenic infection in the pre-formed space between the inner surface of the dura mater and the outer surface of the arachnoid layer. Purulent collections generally accumulate on top of brain convexity,[

The surgical challenge posed by parafalcine SDEs, along with the controversy regarding their treatment strategy,[

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 21-year-old female came to the emergency room with fever, headache, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and left-side hemiparesis. Her Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission was 15 and she had no signs of meningeal irritation. Three weeks earlier she had undergone endoscopic sinonasal surgery, and the day before hospital admission, her ear-nose- throat surgeon prescribed oral antibiotics for acute sinusitis. No cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula was noticed. On admission, her body temperature was 39°C, and serological examination revealed an increased white blood cell (WBC) count (13.510/mm3) with neutrophilia (12.680/mm3) and elevated C-reactive protein (194.80 mg/L). Non-enhanced cranial computed tomography (CT) scan was considered normal by emergency physicians [

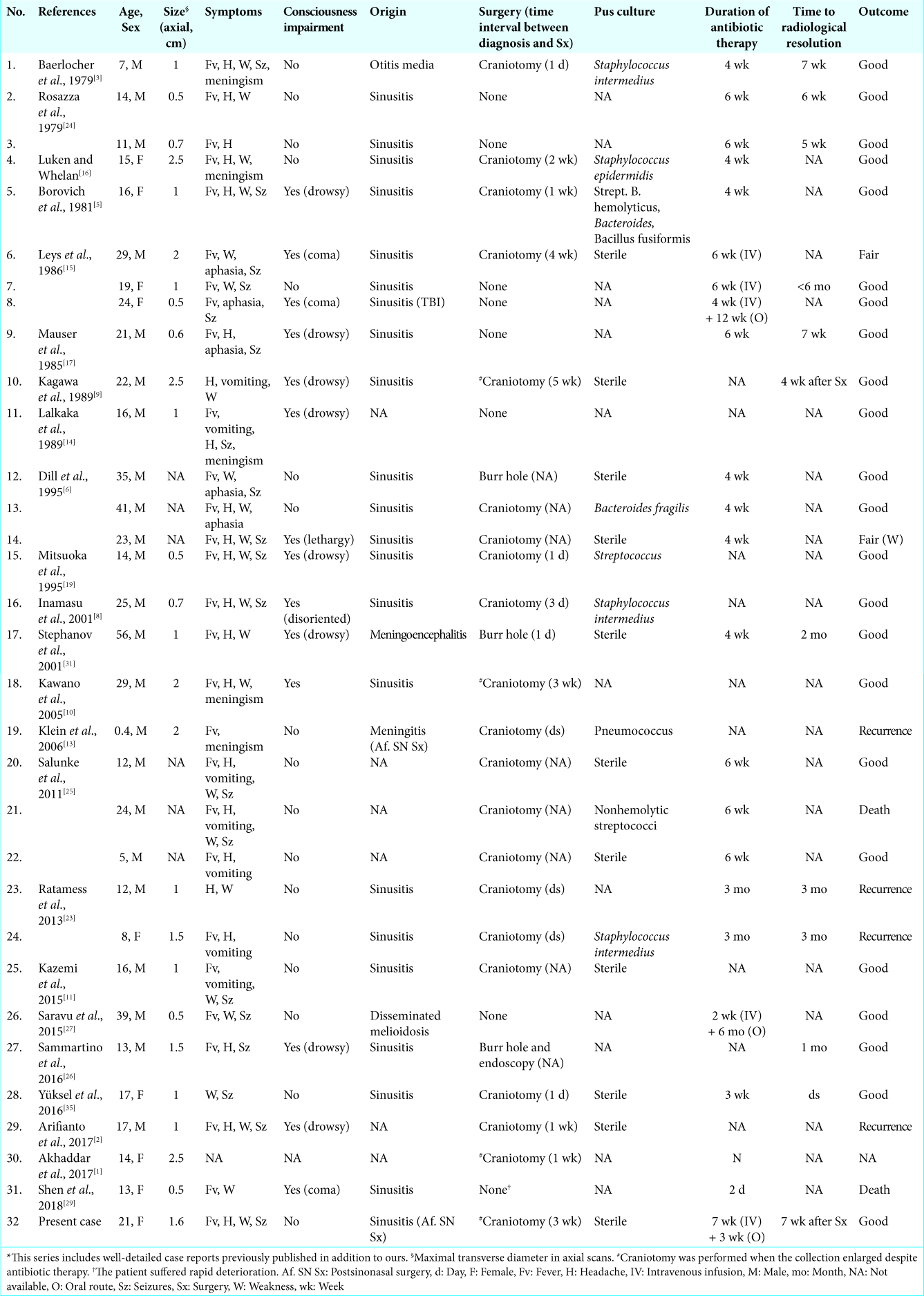

Figure 1:

Preoperative neuroradiological studies. (a) Computed tomography scan performed the day of admission shows a hypodense laminar collection along the right side of the falx (arrow). (b) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed the following day. Axial (b1) and coronal (b2) T1 images confirm a frontoparietal interhemispheric collection without any mass effect. Collection shows high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging (b = 1000 s/mm2, b3) and reduced water diffusion in apparent diffusion coefficient map (b4). (c) Study performed during the 2nd week of antibiotic therapy. T1-weighted, contrast-enhanced MRI (c1-c3) shows enlargement of the interhemispheric collection. c4: T2-weighted MRI demonstrates a hyperintense collection. (d) MRI performed during the 3rd week. d1-d3: Additional enlargement of the collection is demonstrated. d4: Fluid attenuated inversion recovery MRI demonstrates hyperintense areas in the brain adjacent to the collection (arrows).

Suspecting an interhemispheric SDE of nasosinusal origin, the patient was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics including cefepime, metronidazole, and vancomycin. The last was later substituted for linezolid. She experienced progressive clinical improvement except for two episodes of the left leg focal seizures, which resolved after a second anti-epileptic drug was administered. Two weeks after admission, the patient’s fever, headache, and seizures had completely resolved, and the left hemiparesis had noticeably improved. Nevertheless, control MRI demonstrated a notable enlargement of the subdural collection [22 cm3,

A large right parasagittal frontoparietal craniotomy was performed [

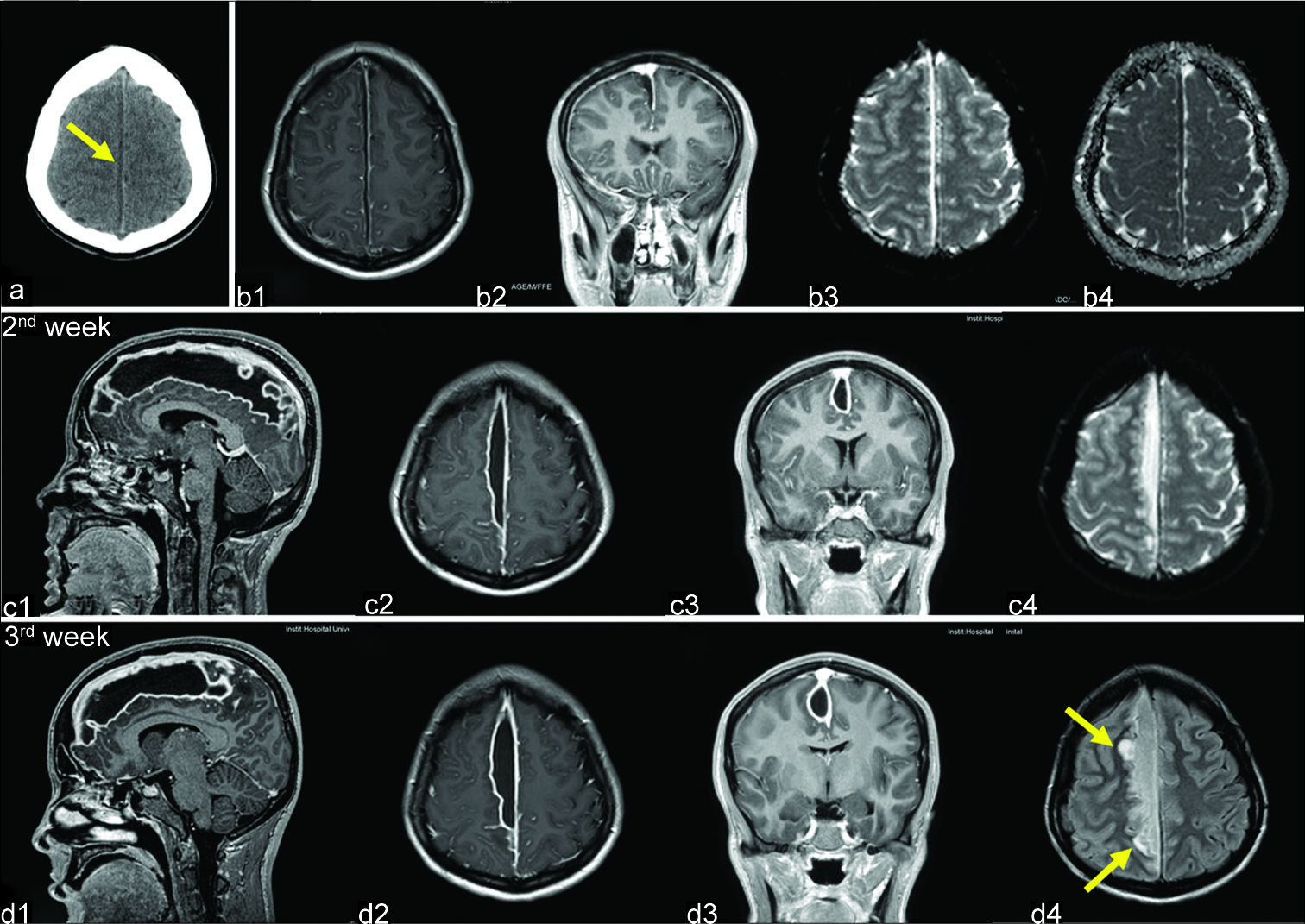

Figure 2:

Operative photographs. (a) The patient is placed in the supine position. A bicoronal skin incision was performed. (b) A large right parasagittal frontoparietal craniotomy was performed. (c) Following dura opening, a swollen brain was found. White liquid pus (arrow) was drained between two bridging veins (green arrowheads). (d) The subdural compartment was washed out, anteriorly and posteriorly, between the two bridging veins (green arrowheads) with saline and antibiotics using a soft rubber catheter.

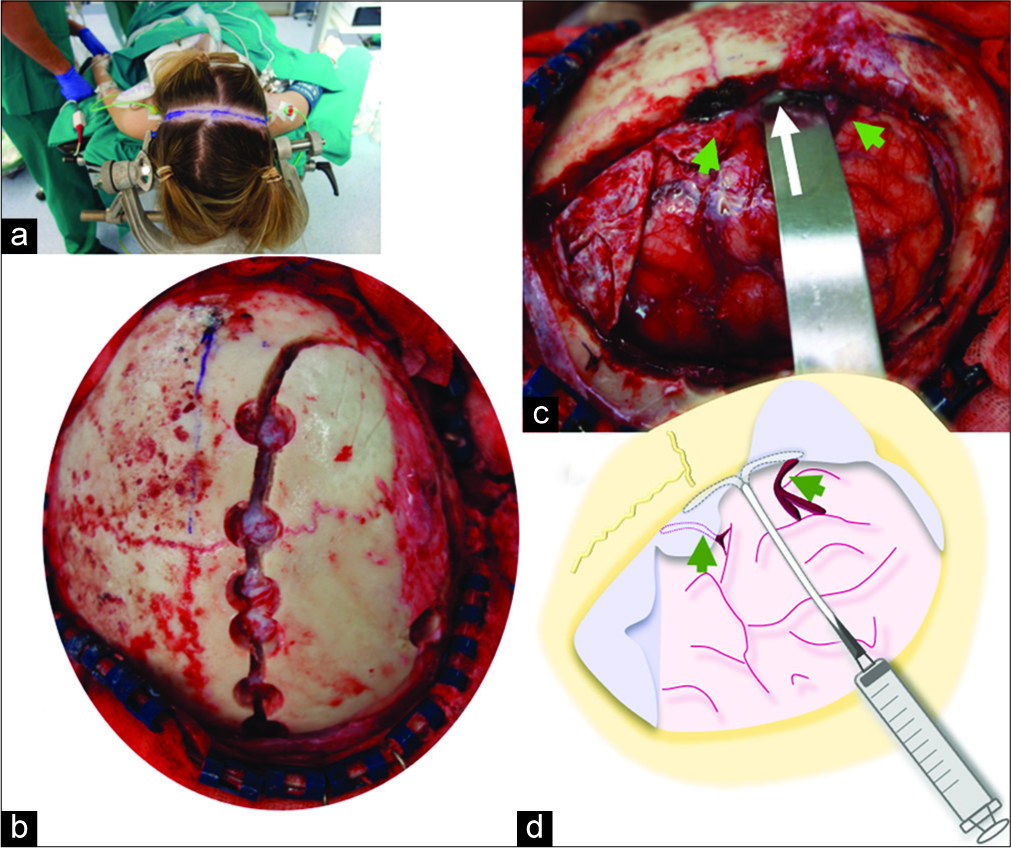

Figure 3:

Postoperative neuroradiological studies. (a) Computed tomography scan performed the day after surgery shows a notable reduction of the interhemispheric collection. (b-d) Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) demonstrate progressive reduction of the collection (asterisk) along the right falx, which completely disappeared in the 7th week after surgery (d). Hyperintense areas of the adjacent brain on T2-weighted MRI (b3, arrows) also resolved in the last MRI study (d3).

DISCUSSION

Nowadays, most clinicians have the general belief that most appropriate treatment of SDE is prompt surgery combined with long-term antibiotics.[

The absolute necessity of surgical drainage is uncertain.[

Controversy over the treatment strategy of SDEs is even higher for the rare cases located in the parafalcine compartment given the difficulty in reaching the interhemispheric fissure with brain swelling. Even gentle manipulation may aggravate contralateral hemiparesis, as is illustrated by our case. The specific location of these collections below the sagittal sinus and bridging veins implies that less aggressive surgical procedures such as burr holes are not safe unless neuronavigation is used.[

Total recovery with empirical antibiotic therapy alone, without specific knowledge of the causal organisms, was reported in 7 parafalcine SDEs. Six of these cases were published from the late 1970s to the late 1980s, coinciding with the development of better antibiotics.[

Regarding the theoretical longer course of antibiotics and the necessity of strict radiological monitoring that some authors use to reason against conservative treatment, this seems quite a weak argument. Regardless of the treatment strategy, antibiotic therapy lasted around 4–6 weeks in this series of parafalcine SDEs. In our case, a relatively long duration of antibiotics was indicated because neuroradiological alterations were not completely resolved until 7 weeks after the operation. Therefore, the experience accumulated with parafalcine SDEs seems to call into question the absolute need for surgical treatment, particularly in those patients with early improvement with antimicrobial therapy who present a good clinical condition and no major midline shift on neuroradiological studies. Further studies are needed to define a decision tree which would help clinicians decide on the best treatment option for such a rare intracranial infectious disease.

CONCLUSION

The mainstay of treatment for parafalcine SDE is early and long-term antibiotic therapy. The absolute necessity to operate this rare entity was challenged by six reports published in the 1980s. A nonsurgical strategy might be contemplated for patients with a good clinical condition and no major midline shift on neuroradiological studies. On the contrary, surgery should be considered for those cases with a notable volume increase despite antibiotic therapy. When the decision is to associate surgical drainage, broad-range 16S rDNA PCR of the empyema is strongly recommended to identify the causative organism as pus cultures are usually sterile.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Crystal Smith and Liliya Gusakova, reference librarians of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) for their generous assistance during the process of retrieving some of the original articles used in this study. We are also grateful to George Hamilton for his critical review of the language and style of the manuscript.

References

1. Akhaddar A.editors. Cranial subdural empyemas. Atlas of Infections in Neurosurgery and Spinal Surgery. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 51-64

2. Arifianto MR, Ma’ruf AZ, Ibrahim A, Bajamal AH. Interhemispheric and infratentorial subdural empyema with preseptal cellulitis as complications of sinusitis: A case report. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2018. 53: 128-33

3. Baerlocher K, Arregger G, Benini A, Gaspar B, Valavanis A, Schubiger O. Subdural interhemispheric empyema in a 7-year-old boy. Helv Paediatr Acta. 1979. 34: 583-8

4. Bok AP, Peter JC. Subdural empyema: Burr holes or craniotomy? A retrospective computerized tomography-era analysis of treatment in 90 cases. J Neurosurg. 1993. 78: 574-8

5. Borovich B, Braun J, Honigman S, Joachims HZ, Peyser E. Supratentorial and parafalcial subdural empyema diagnosed by computerized tomography. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1981. 54: 105-7

6. Dill SR, Cobbs CG, McDonald CK. Subdural empyema: Analysis of 32 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995. 20: 372-86

7. Hitchcock E, Andreadis A. Subdural empyema: A review of 29 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1964. 27: 422-34

8. Inamasu J, Horiguchi T, Saito R, Nakamura Y, Ichikizaki K, Takahashi K. Interhemispheric subdural empyema in a young man. Am J Emerg Med. 2001. 19: 602-3

9. Kagawa R, Shima T, Matsumura S, Okada Y, Nishida M, Yamada T. Primary interhemispheric subdural abscess: Report of a case. No Shinkei Geka. 1989. 17: 647-52

10. Kawano H, Yonemura K, Misumi Y, Hashimoto Y, Hirano T, Uchino M. A case of interhemispheric subdural empyema with sinusitis diagnosed by diffusion-weighted MRI. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2005. 45: 449-52

11. Kazemi KA, Pishjoo M, Safdari Z. Interhemispheric subdural empyema in 16 years old boy, a case report. Int J Med Invest. 2015. 4: 407-9

12. Keith WS. Subdural empyema. J Neurosurg. 1949. 6: 127-39

13. Klein O, Freppel S, Schuhmacher H, Pinelli C, Auque J, Marchal JC. Empyèmes sous-duraux de l’enfant: Stratégie thérapeutique. Neurochirurgie. 2006. 52: 111-8

14. Lalkaka JA, Parikh JM, Nath AR, Meisheri YV, Vengsarkar US, Deshpande DV. Interhemispheric empyema. An unusual form of subdural empyema. J Assoc Physicians India. 1989. 37: 394-6

15. Leys D, Destee A, Petit H, Warot P. Management of subdural intracranial empyemas should not always require surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986. 49: 635-9

16. Luken MG, Whelan MA. Recent diagnostic experience with subdural empyema. J Neurosurg. 1980. 52: 764-71

17. Mauser HW, Ravijst RA, Elderson A, van Gijn J, Tulleken CA. Nonsurgical treatment of subdural empyema. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1985. 63: 128-30

18. Miller ES, Dias PS, Uttley D. Management of subdural empyema: A series of 24 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987. 50: 1415-8

19. Mitsuoka H, Tsunoda A, Mori K, Tajima A, Maeda M. Hypertrophic anterior falx artery associated with interhemispheric subdural empyema case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1995. 35: 830-2

20. Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, Gouws E, van Dellen JR. Craniotomy improves outcomes for cranial subdural empyemas: Computed tomography-era experience with 699 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001. 49: 872-7

21. Patel A, Harris KA, Fitzgerald F. What is broad-range 16S rDNA PCR. ? Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017. 102: 261-4

22. Pathak A, Sharma BS, Mathuriya SN, Khosla VK, Khandelwal N, Kak VK. Controversies in the management of subdural empyema. A study of 41 cases with review of literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1990. 102: 25-32

23. Ratamess NA. Announcement: New JSCR article format. J Strength Cond Res. 2019. 33: 1179-

24. Rosazza A, de Tribolet N, Deonna T. Nonsurgical treatment of interhemispheric subdural empyemas. Helv Paediatr Acta. 1979. 34: 577-81

25. Salunke PS, Malik V, Kovai P, Mukherjee KK. Falcotentorial subdural empyema: Analysis of 10 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2011. 153: 164-9

26. Sammartino F, Feletti A, Fiorindi A, Mazzucco GM, Longatti P. Aspiration of parafalcine empyemas with flexible scope. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016. 32: 1123-9

27. Saravu K, Kadavigere R, Shastry AB, Pai R, Mukhopadhyay C. Neurologic melioidosis presented as encephalomyelitis and subdural collection in two male labourers in India. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015. 9: 1289-93

28. Shearman CP, Lees PD, Taylor JC. Subdural empyema: A rational management plan. The case against craniotomy. Br J Neurosurg. 1987. 1: 179-83

29. Shen YY, Cheng ZJ, Chai JY, Dai TM, Luo Y, Guan YQ. Interhemispheric subdural empyema secondary to sinusitis in an adolescent girl. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018. 131: 2989-90

30. Sogoba Y, Kanikomo D, Coulibaly O, Singaré K, Maiga Y, Samaké D. Nonsurgical treatment of infratentorial subdural empyema: A case report. Case Rep Clin Med. 2013. 2: 294-7

31. Stephanov S, Sidani AH, Amacker JJ. Interhemispheric subdural empyema case report. Swiss Surg. 2001. 7: 229-32

32. Stephanov S, Sidani AH. Intracranial subdural empyema and its management. A review of the literature with comment. Swiss Surg. 2002. 8: 159-63

33. Venkatesh MS, Pandey P, Devi BI, Khanapure K, Satish S, Sampath S. Pediatric infratentorial subdural empyema: Analysis of 14 cases. J Neurosurg. 2006. 105: 370-7

34. Wong AM, Zimmerman RA, Simon EM, Pollock AN, Bilaniuk LT. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of subdural empyemas in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004. 25: 1016-21

35. Yüksel MO, Gürbüz MS, Karaarslan N, Caliskan T. Rapidly progressing interhemispheric subdural empyema showing a three-fold increase in size within 12 hours: Case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2016. 7: S872-5