- Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery, Santa Casa de Sao Paulo School of Medical Sciences, São Paulo, Brazil

Correspondence Address:

Guilherme Brasileiro de Aguiar

Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery, Santa Casa de Sao Paulo School of Medical Sciences, São Paulo, Brazil

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.175898

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: de Aguiar GB, Mário Vítor Caldeira Pagotto, Marques Conti ML, José Carlos Esteves Veiga. Spontaneous thrombosis of giant intracranial aneurysm and posterior cerebral artery followed by also spontaneous recanalization. Surg Neurol Int 08-Feb-2016;7:15

How to cite this URL: de Aguiar GB, Mário Vítor Caldeira Pagotto, Marques Conti ML, José Carlos Esteves Veiga. Spontaneous thrombosis of giant intracranial aneurysm and posterior cerebral artery followed by also spontaneous recanalization. Surg Neurol Int 08-Feb-2016;7:15. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/spontaneous-thrombosis-of-giant-intracranial-aneurysm-and-posterior-cerebral-artery-followed-by-also-spontaneous-recanalization/

Abstract

Background:Spontaneous complete thrombosis of a giant aneurysm and its parent artery is a rare event. Their spontaneous recanalization is even rarer, with few reports.

Case Description:A 17-year-old male patient presenting blurred vision and headache, with a history of seizures, was referred to our service. After further investigation with cranial computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cerebral angiography (CAG), it was diagnosed a thrombosed aneurysm of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and also complete thrombosis of the PCA. Three years later, he experienced visual worsening. A new MRI scan indicated flow both through the aneurysm and the left PCA, which was further confirmed by CAG. We decided for a noninterventional treatment combined with strict clinical follow-up. The patient continues to present with the previous neurological deficit, without recurrence of headaches.

Conclusions:Thrombosis is not the final event in the natural history of giant aneurysms, and partial thrombosis does not preclude the risk of rupture. Thrombosed aneurysms may display additional growth brought about by wall dissections or intramural hemorrhages. Their treatment may be either surgical or involve endovascular procedures such as embolization. Thrombosed giant aneurysms are dynamic and unstable lesions. A noninterventional treatment is feasible, but aneurysmal growth or recanalization may suggest the need for a more active intervention.

Keywords: Giant intracranial aneurysm, intracranial aneurysm, intracranial thrombosis, posterior cerebral artery

INTRODUCTION

Although thrombosis in giant aneurysms is a relatively common phenomenon, complete thrombosis is uncommon, and usually spares the parent vessel.[

Recanalization of thrombosed aneurysms, although recorded in the literature, is a rare event.[

CASE REPORT

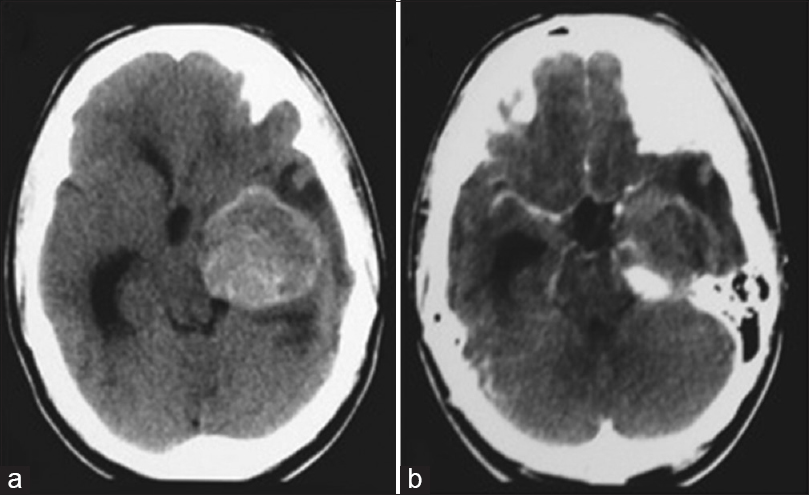

A 17-year-old male patient was admitted to a different institution than ours complaining of blurred vision, headache, and three episodes of generalized tonic-clonic seizures, which had occurred 3 months before his admission. Upon neurological examination, the single alteration found was a visual deficit, observed with a direct confrontation visual field examination. A campimetry examination showed right homonymous hemianopsia. A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan showed a hyperdense expansive lesion adjacent to the left PCA [

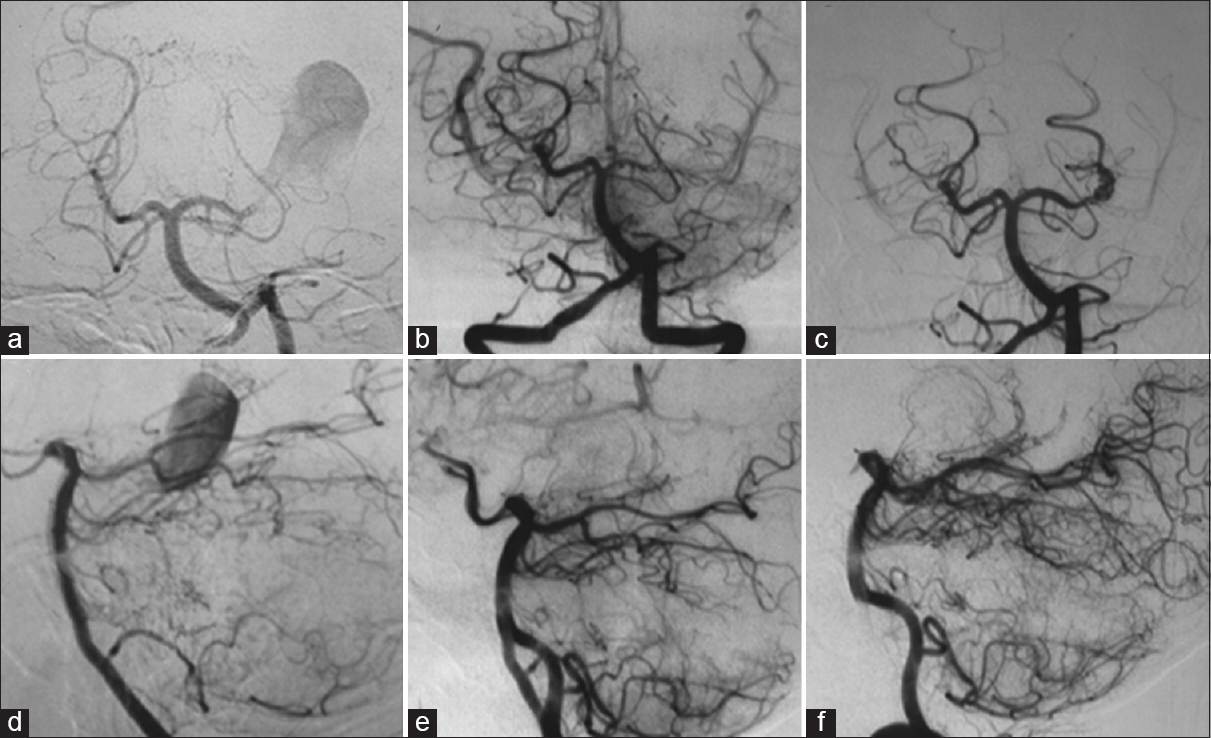

Figure 2

Left vertebral angiography showing a giant aneurysm of the left posterior cerebral artery (a and d); left vertebral angiography after 1 month demonstrating the occlusion of the left posterior cerebral artery at its P2 segment, without opacification of the aneurysm (b and e); (c and f) left vertebral angiography performed 3 years after the first one, showing recanalization of the left posterior cerebral artery and aneurysm (a, b, and c: Towne's view; d, e, and f: Lateral view)

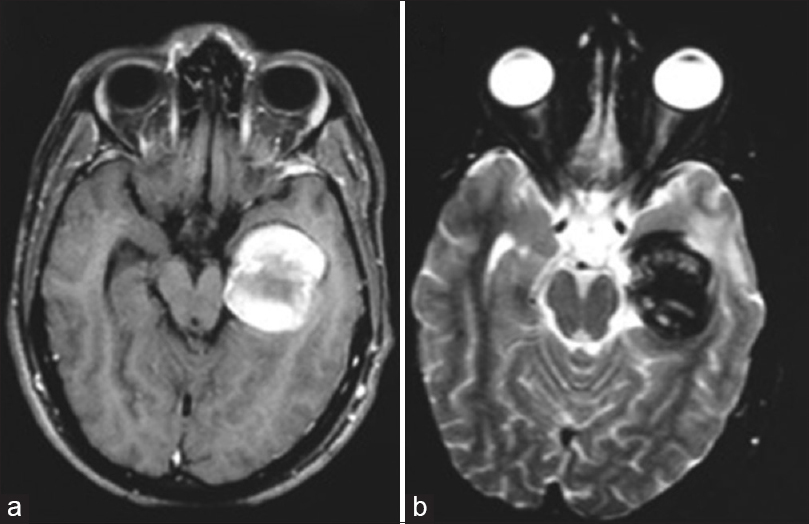

One month later, the patient was sent for endovascular treatment in our service. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed and showed a lesion with the heterogeneous signal, suggesting a totally thrombosed giant aneurysm of the P2 segment of the left PCA, with occlusion of the artery at its P2 segment [Figure

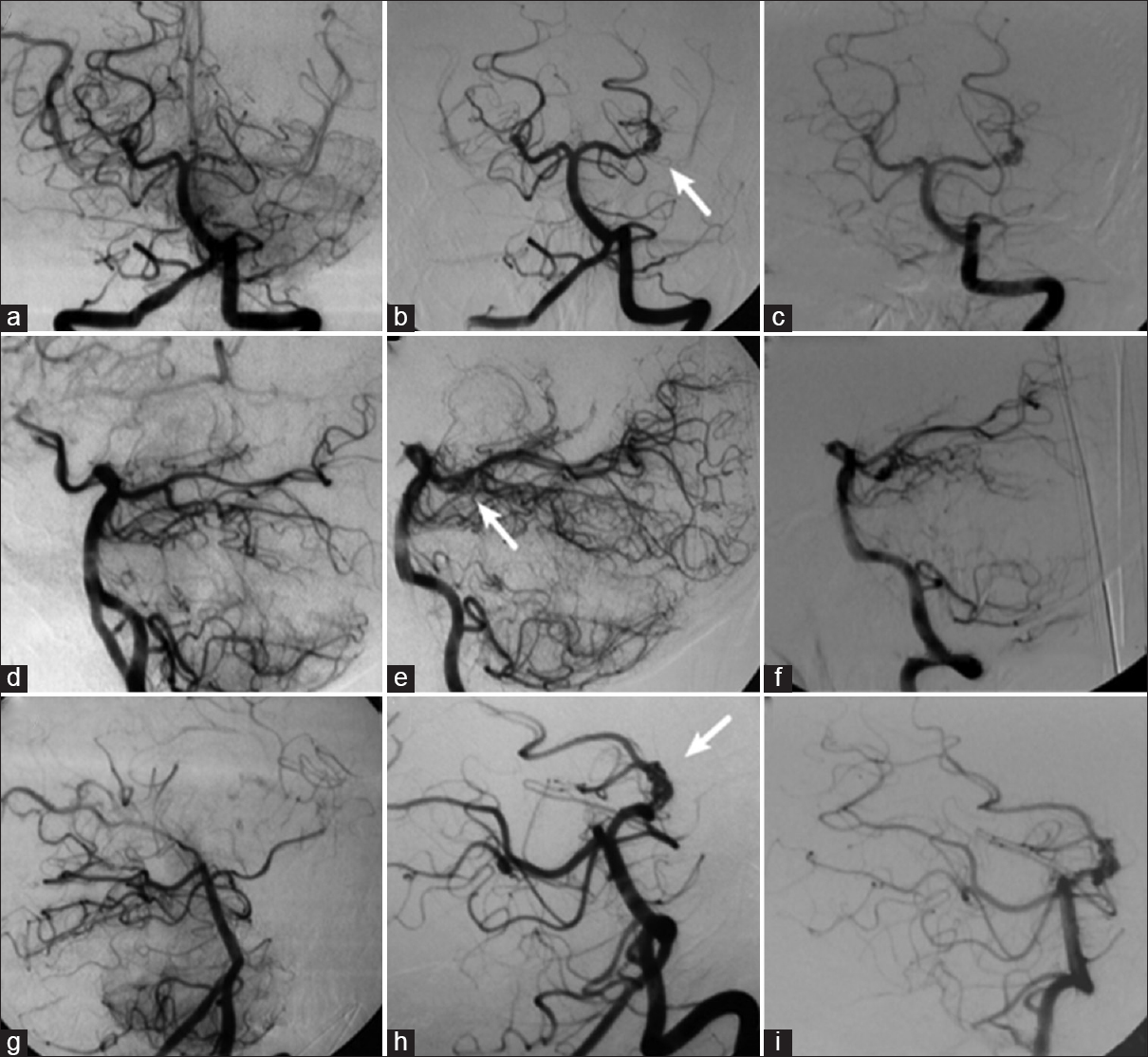

About 3 years after, the patient experienced visual worsening, having come back to our service. A cranial MRI scan was then performed, which showed flow through both the left PCA and its aneurysm, with no signs of bleeding. A CAG was also conducted, which confirmed the spontaneous recanalization of the aneurysm and the PCA [Figure

We chose a noninterventional treatment aimed at managing the condition, with strict clinical follow-up. A CAG performed 1 year later revealed the patency of both the aneurysm and the left PCA, with no major differences in comparison with the previous examination [

Figure 4

Left vertebral angiography demonstrating occlusion of the left posterior cerebral artery at its P2 segment, without opacification of the aneurysm (a, d, and g); in (b, e, and h), the left vertebral angiography performed 3 years after the occlusion shows recanalization of the left posterior cerebral artery and aneurysm (arrow); in (c, f, and i), the new left vertebral angiography shows unchanged aspect of the aneurysm 1 year after recanalization (a, b, and c: Towne's view; d, e, and f: Lateral view; g, h, and i: Right anterior oblique view)

DISCUSSION

Aneurysms with a diameter as large as 25 mm or more are classified as giant aneurysms.[

Spontaneous partial thrombosis of giant aneurysms is a fairly common finding, occurring in up to 60% of such lesions.[

The additional growth of thrombosed giant aneurysms is a well-described phenomenon. The suggested pathophysiological mechanisms for this growth include successive aneurysmal wall dissections;[

Some authors[

The close relationship among the PCA, mesencephalon, and cranial nerves renders the giant aneurysms of the PCA particularly prone to cause a mass effect.[

Despite the fact that spontaneous thrombosis is more frequently associated with giant aneurysms than with nongiant ones,[

CAG is the gold standard for diagnosing intracranial aneurysms. Its major advantage is the possibility of a detailed assessment of the vascular anatomy, including the study of aneurysmal orientation through multiple planes.[

In such context, CT angiography and MR angiography both seem to be more suitable for the measuring the volume of partially thrombosed aneurysms.[

In precontrast MRI scans, an “onion-skin” lesion, characterized by layers with different signal intensities, points to the presence of an aneurysmal thrombus.[

Given the rarity of giant aneurysms of the P2-segment of the PCA, there are no major clinical trials assessing the specific therapeutic modalities for treating such lesions. The potential complications of thrombosed giant aneurysms lead to judicious appraisal on the need for intervention. The treatment goals are to prevent bleedings, relief the mass effect, and maintain an appropriate brain perfusion.[

The endovascular therapeutic modalities include aneurysm embolization using platinum coils or, more recently, flow-diverting stents. These techniques aim at the occlusion of the aneurysm while sparing the flow in the parent vessel. Another strategy is the therapeutic occlusion of the parent vessel (OPV) and the aneurysm.[

The surgical options include aneurysmal clipping followed by thrombectomy and aneurysmal trapping either with or without revascularization. Given the possibility of thrombus dislodgment and distal embolism, surgical manipulation must be careful.[

In this case, recanalization occurred in the artery and in the aneurysm neck only. Thus, only the most proximal portion of the aneurysm was recanalized, and this small region has not increased in size during follow-up. Hence, with no increase in a lesion with mass effect, and not occurring worsening of patient's symptoms, it was opted for a conservative treatment.

CONCLUSION

Thrombosed giant aneurysms are dynamic and unstable lesions, being prone to spontaneous recanalization and additional growth. There is no consensus about the ideal management of such lesions. A noninterventionist management approach is possible but requires strict follow-up, including serial imaging examinations. Any worsening in the neurological status or evidence of either recanalization or growth may be suggestive of the need for a direct approach.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Atlas SW, Grossman RI, Goldberg HI, Hackney DB, Bilaniuk LT, Zimmerman RA. Partially thrombosed giant intracranial aneurysms: Correlation of MR and pathologic findings. Radiology. 1987. 162: 111-4

2. Batjer HH, Purdy PD. Enlarging thrombosed aneurysm of the distal basilar artery. Neurosurgery. 1990. 26: 695-9

3. Brownlee RD, Tranmer BI, Sevick RJ, Karmy G, Curry BJ. Spontaneous thrombosis of an unruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm.An unusual cause of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1995. 26: 1945-9

4. Calviere L, Viguier A, Da Silva NA, Cognard C, Larrue V. Unruptured intracranial aneurysm as a cause of cerebral ischemia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011. 113: 28-33

5. Choi IS, David C. Giant intracranial aneurysms: Development, clinical presentation and treatment. Eur J Radiol. 2003. 46: 178-94

6. Cohen JE, Itshayek E, Gomori JM, Grigoriadis S, Raphaeli G, Spektor S. Spontaneous thrombosis of cerebral aneurysms presenting with ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2007. 254: 95-8

7. Dengler J, Maldaner N, Bijlenga P, Burkhardt JK, Graewe A, Guhl S. Perianeurysmal edema in giant intracranial aneurysms in relation to aneurysm location, size, and partial thrombosis. J Neurosurg. 2015. 123: 446-52

8. Ferns SP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, van den Berg R, Majoie CB. Partially thrombosed intracranial aneurysms presenting with mass effect: Long-term clinical and imaging follow-up after endovascular treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. 31: 1197-205

9. Krings T, Alvarez H, Reinacher P, Ozanne A, Baccin CE, Gandolfo C. Growth and rupture mechanism of partially thrombosed aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2007. 13: 117-26

10. Lee KC, Joo JY, Lee KS, Shin YS. Recanalization of completely thrombosed giant aneurysm: Case report. Surg Neurol. 1999. 51: 94-8

11. Martin AJ, Hetts SW, Dillon WP, Higashida RT, Halbach V, Dowd CF. MR imaging of partially thrombosed cerebral aneurysms: Characteristics and evolution. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011. 32: 346-51

12. Mehta RI, Salamon N, Zipser BD, Mehta RI. Best cases from the AFIP: Giant intracranial aneurysm. Radiographics. 2010. 30: 1133-8

13. Schaller B, Lyrer P. Focal neurological deficits following spontaneous thrombosis of unruptured giant aneurysms. Eur Neurol. 2002. 47: 175-82

14. Schubiger O, Valavanis A, Hayek J. Computed tomography in cerebral aneurysms with special emphasis on giant intracranial aneurysms. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1980. 4: 24-32

15. Schubiger O, Valavanis A, Wichmann W. Growth-mechanism of giant intracranial aneurysms; demonstration by CT and MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1987. 29: 266-71

16. Sharma S. Evolution of giant P2-posterior cerebral artery aneurysm over 16 years: Saccular to serpentine.A case report. Neuroradiol J. 2009. 22: 605-11

17. Silva JM, Aguiar GB, Conti ML, Veiga JC. Spontaneous thrombosis of aneurysm and posterior cerebral artery. Rev Chil Neurocir. 2013. 39: 172-5

18. Teng MM, Nasir Qadri SM, Luo CB, Lirng JF, Chen SS, Chang CY. MR imaging of giant intracranial aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci. 2003. 10: 460-4

19. Türe U, Elmaci I, Ekinci G, Pamir MN. Totally thrombosed giant P2 aneurysm: A case report and review of literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2003. 10: 115-20

20. Vorkapic P, Czech T, Pendl G, Oztürk E, Horaczek A. Clinico-radiological spectrum of giant intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurg Rev. 1991. 14: 271-4

21. Westerlaan HE, van Dijk JM, Jansen-van der Weide MC, de Groot JC, Groen RJ, Mooij JJ. Intracranial aneurysms in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: CT angiography as a primary examination tool for diagnosis - Systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2011. 258: 134-45

22. Whittle IR, Dorsch NW, Besser M. Spontaneous thrombosis in giant intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1982. 45: 1040-7

23. Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, Meissner I, Brown RD, Piepgras DG. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003. 362: 103-10