- Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Heliópolis, São Paulo, Brazil

- Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

Correspondence Address:

Breno Nery

Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Heliópolis, São Paulo, Brazil

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.173307

Copyright: © 2016 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Nery B, Araujo R, Burjaili B, Smith TR, Rodrigues JC, Silva MN. “True” posterior communicating aneurysms: Three cases, three strategies. Surg Neurol Int 05-Jan-2016;7:2

How to cite this URL: Nery B, Araujo R, Burjaili B, Smith TR, Rodrigues JC, Silva MN. “True” posterior communicating aneurysms: Three cases, three strategies. Surg Neurol Int 05-Jan-2016;7:2. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/true-posterior-communicating-aneurysms-three-cases-three-strategies/

Abstract

Background:The authors provide a review of true aneurysms of the posterior communicating artery (PCoA). Three cases admitted in our hospital are presented and discussed as follows.

Case Descriptions:First patient is a 51-year-old female presenting with a Fisher II, Hunt-Hess III (headache and confusion) subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) from a ruptured true aneurysm of the right PCoA. She underwent a successful ipsilateral pterional craniotomy for aneurysm clipping and was discharged on postoperative day 4 without neurological deficit. Second patient is a 53-year-old female with a Fisher I, Hunt-Hess III (headache, mild hemiparesis) SAH and multiple aneurisms, one from left ophthalmic carotid artery and one (true) from right PCoA. These lesions were approached and successfully treated by a single pterional craniotomy on the left side. The patient was discharged 4 days after surgery, with complete recovery of muscle strength during follow-up. Third patient is a 69-year-old male with a Fisher III, Hunt-Hess III (headache and confusion) SAH, from a true PCoA on the right. He had a left subclavian artery occlusion with flow theft from the right vertebral artery to the left vertebral artery. The patient underwent endovascular treatment with angioplasty and stent placement on the left subclavian artery that resulted in aneurysm occlusion.

Conclusion:In conclusion, despite their seldom occurrence, true PCoA aneurysms can be successfully treated with different strategies.

Keywords: Etiology, physiopathology, treatment, true posterior communicating artery aneurysms

INTRODUCTION

Twenty-five percent of intracranial aneurysms arise from the internal carotid artery (ICA) at the posterior communicating artery (PCoA) origin, making this site the second most common location after anterior communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysms.[

CASE REPORTS

Case report 1

L.M.S is a 51-year-old who experienced a paroxysmal, severe headache along with confusion and presented to a secondary hospital emergency department within a few hours of onset. She had a medical history of poorly controlled hypertension, and a significant smoking history (40 cigarettes/day for 20 years). A computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with the preponderance of hemorrhage centered in the right Sylvian fissure. A clinical diagnosis of aneurysmal SAH (Hunt and Hess Grade III, Fisher Grade II) was made.

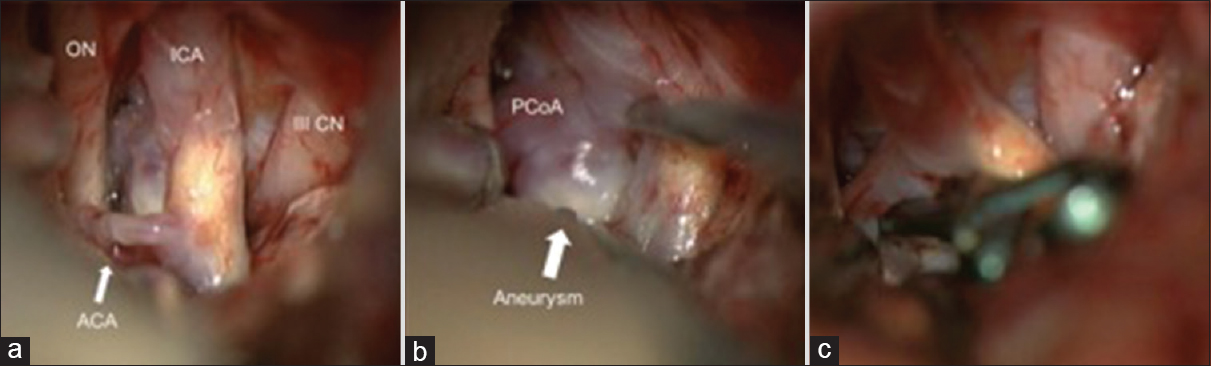

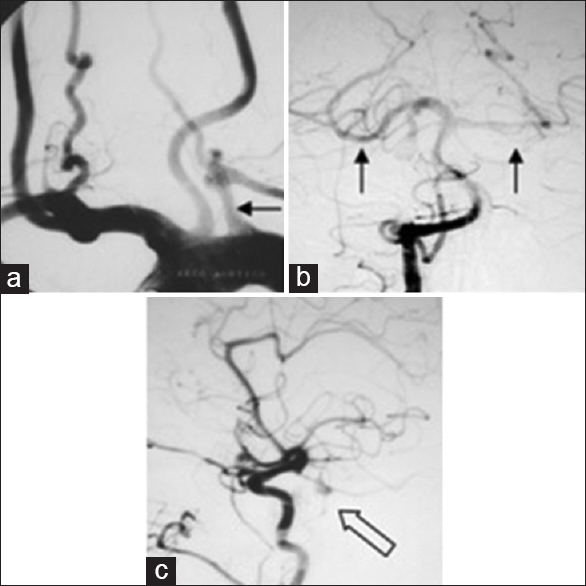

Four-vessel digital subtraction angiography (DSA) revealed a small, true saccular aneurysm with a fetal-type right PCoA. The aneurysm was 3 mm × 4 mm in size, with a postero-superiorly directed 2 mm neck [

Figure 1

Lateral view of right internal carotid artery angiography performed on June 18, 2012. Small true saccular aneurysm (white arrow) of the right posterior communicating artery, 3 mm × 4 mm size, neck diameter of 2 mm, postero-superiorly directed, and fetal pattern of ipsilateral posterior communicating artery

Case report 2

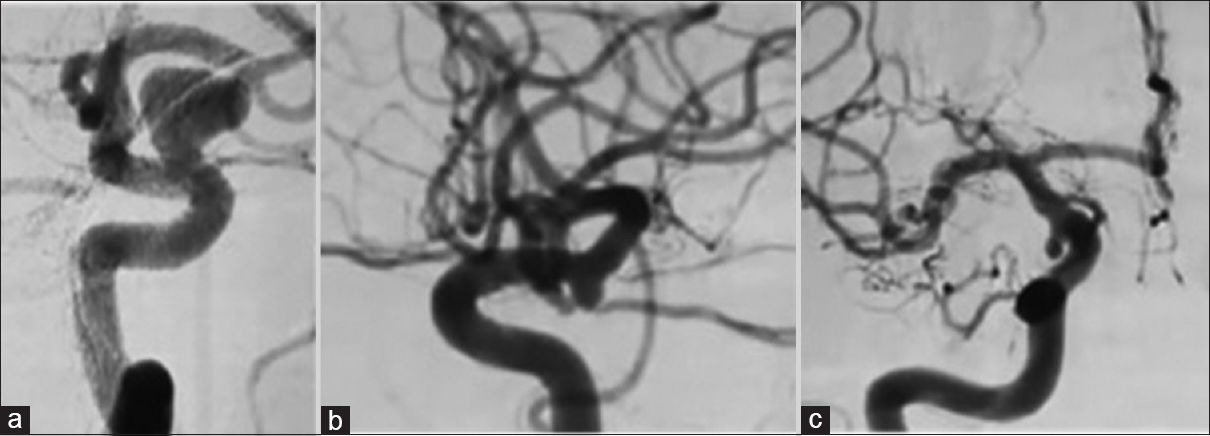

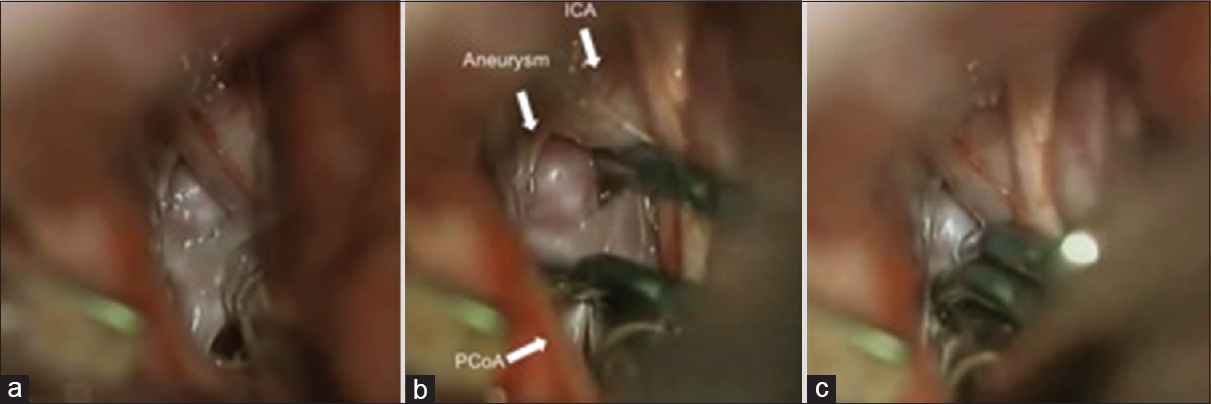

M.C.S., a 53-year-old female, with a previous history of hypertension and smoke (20 cigarettes/day for 30 years), presented a headache of moderate intensity for 5 days, in the occiptocervical region, partially responsive to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, followed by a sudden increase in pain intensity, along with right-sided hemiparesis, when she was admitted in a secondary hospital. The head CT was normal, but a lumbar puncture demonstrated SAH (Hunt and Hess Grade III, Fisher Grade I). The four-vessel DSA then revealed a true saccular aneurysm of the right PCoA, 6 mm × 3 mm in size, inferiorly oriented, with a 2 mm neck, and a saccular aneurysm of the left ophthalmic segment of ICA, 12 mm × 10 mm in size, superiorly oriented, with a 5 mm neck [

Figure 3

(a) Contralateral oblique view of left internal carotid artery angiography, with a saccular aneurysm of the ophthalmic segment, 12 mm × 10 mm, 5 mm neck. (b) Lateral and (c) anteroposterior views of right internal carotid artery angiography, with a true saccular aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery, 6 mm × 3 mm, 2 mm neck

Case report 3

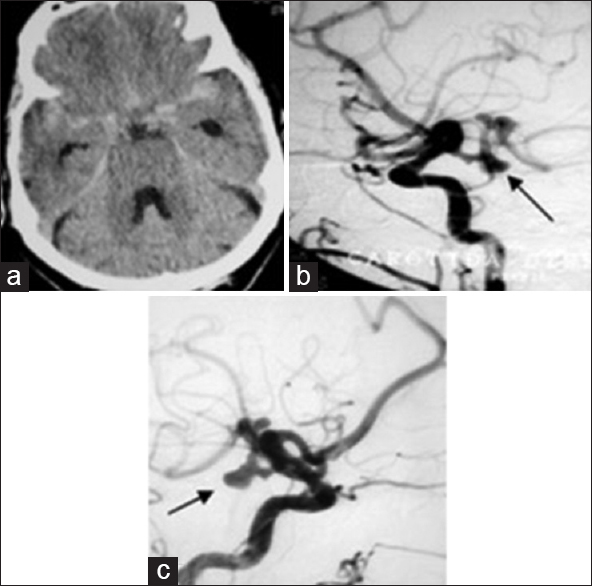

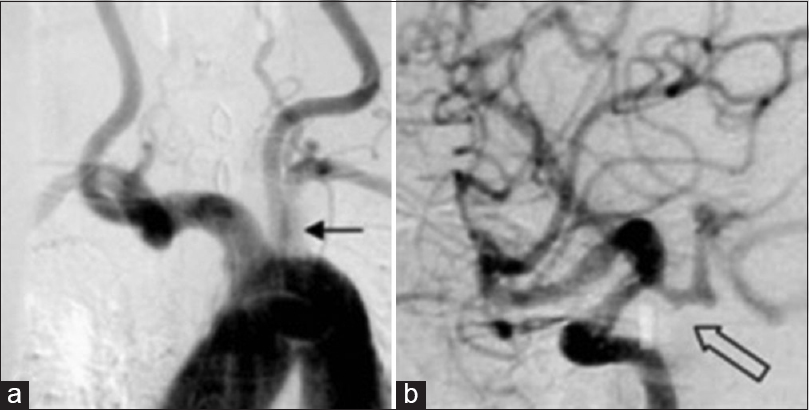

A 69-year-old male patient presented to a secondary hospital emergency department with a sudden headache followed by momentary loss of conscience and cranial nerve paresis. After 18 days of the initial symptoms, he was transferred to our hospital. By physical examination after admission, the patient presented with slight headache and neck stiffness, blood pressure on left arm of 140 mmHg × 110 mmHg and right arm of 170 mmHg × 100 mmHg. Neurological exam showed a conscious and oriented patient with right oculomotor (III) and trochlear (IV) paresis. The CT scan revealed a Fisher Grade III SAH [

Figure 7

(a) Aortic arch angiogram showing the arterioplasty procedure and stent placing on the left subclavian artery (black arrow). (b) Left vertebral angiogram after arterioplasty with adequate filling of the vertebrobasilar circulation and posterior cerebral arteries. (c) Right internal carotid artery after arterioplasty and diminished flow on the posterior communicating artery with contrast stagnation inside the aneurysm (empty black arrow)

DISCUSSION

True PCoA aneurysms are rare with pooled data revealing that they represent 1.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8–1.7%) of all intracranial aneurysms, and 6.8% (95% CI 4.3–9.2%) of all PCoA aneurysms.[

There is a paucity of literature regarding the pathophysiology of true PCoA aneurysm. Aneurysms of the PCoA can occur at the junction with the ICA, PCA or the proximal PCoA itself.[

It is well known that hemodynamic alterations within the ICA from either anatomic/pathologic hypoplastic segments or iatrogenic occlusion can directly influence the development of intracranial aneurysms.[

Microsurgical understanding of this unique anatomy is also essential for minimizing morbidity associated with surgical clipping. It is critical to note that for true PCoA aneurysms, the neck arises distal to the origin of the PCoA, and therefore resides in what is traditionally considered an intra-operative “blind spot.” The PCoA must be followed posteriorly to visualize the aneurysm neck for microsurgical clipping.[

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, true PCoA aneurysms are rare. Much is still unclear regarding its pathophysiology. Preoperative anatomical understanding and microsurgical facility are paramount for treatment, and special consideration must be paid to the perforating arteries. The seldom occurrence of such lesion does not imply that treatment will have a poor outcome, and different strategies may be used.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. de Gast AN, Sprengers ME, van Rooij WJ, Lavini C, Sluzewski M, Majoie CB. Long-term 3T MR angiography follow-up after therapeutic occlusion of the internal carotid artery to detect possible de novo aneurysm formation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007. 28: 508-10

2. Ferns SP, Sprengers ME, van Rooij WJ, van den Berg R, Velthuis BK, de Kort GA. De novo aneurysm formation and growth of untreated aneurysms: A 5-year MRA follow-up in a large cohort of patients with coiled aneurysms and review of the literature. Stroke. 2011. 42: 313-8

3. Gibo H, Lenkey C, Rhoton AL. Microsurgical anatomy of the supraclinoid portion of the internal carotid artery. J Neurosurg. 1981. 55: 560-74

4. He W, Gandhi CD, Quinn J, Karimi R, Prestigiacomo CJ. True aneurysms of the posterior communicating artery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. World Neurosurg. 2011. 75: 64-72

5. He W, Hauptman J, Pasupuleti L, Setton A, Farrow MG, Kasper L. True posterior communicating artery aneurysms: Are they more prone to rupture? A biomorphometric analysis. J Neurosurg. 2010. 112: 611-5

6. Jou LD, Lee DH, Morsi H, Mawad ME. Wall shear stress on ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms at the internal carotid artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008. 29: 1761-7

7. Juvela S, Poussa K, Porras M. Factors affecting formation and growth of intracranial aneurysms: A long-term follow-up study. Stroke. 2001. 32: 485-91

8. Kaspera W, Majchrzak H, Kopera M, Ladzinski P. “True” aneurysm of the posterior communicating artery as a possible effect of collateral circulation in a patient with occlusion of the internal carotid artery. A case study and literature review. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2002. 45: 240-4

9. Kuzmik GA, Bulsara KR. Microsurgical clipping of true posterior communicating artery aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2012. 154: 1707-10

10. Miller CA, Hill SA, Hunt WE. “De novo” aneurysms. A clinical review. Surg Neurol. 1985. 24: 173-80

11. Ogasawara K, Numagami Y, Kitahara M. A case of ruptured true posterior communicating artery aneurysm thirteen years after surgical occlusion of the ipsilateral cervical internal carotid artery. No Shinkei Geka. 1995. 23: 359-63

12. Yoshida M, Watanabe M, Kuramoto S. “True” posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Surg Neurol. 1979. 11: 379-81