- Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical Care, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Pondicherry, India

Correspondence Address:

Prasanna U. Bidkar

Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical Care, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Pondicherry, India

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.199560

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Dhanyasi Shravanalakshmi, Prasanna U. Bidkar, K. Narmadalakshmi, Suman Lata, Sandeep K. Mishra, S. Adinarayanan. Comparison of intubation success and glottic visualization using King Vision and C-MAC videolaryngoscopes in patients with cervical spine injuries with cervical immobilization: A randomized clinical trial. 06-Feb-2017;8:19

How to cite this URL: Dhanyasi Shravanalakshmi, Prasanna U. Bidkar, K. Narmadalakshmi, Suman Lata, Sandeep K. Mishra, S. Adinarayanan. Comparison of intubation success and glottic visualization using King Vision and C-MAC videolaryngoscopes in patients with cervical spine injuries with cervical immobilization: A randomized clinical trial. 06-Feb-2017;8:19. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/comparison-of-intubation-success-and-glottic-visualization-using-king-vision-and-c%e2%80%91mac-videolaryngoscopes-in-patients-with-cervical-spine-injuries-with-cervical-immobilization-a-randomized-cl/

Abstract

Background:Glottic visualization can be difficult with cervical immobilization in patients with cervical spine injury. Indirect laryngoscopes may provide better glottic visualization in these groups of patients. Hence, we compared King Vision videolaryngoscope, C-MAC videolaryngoscope for endotracheal intubation in patients with proven/suspected cervical spine injury.

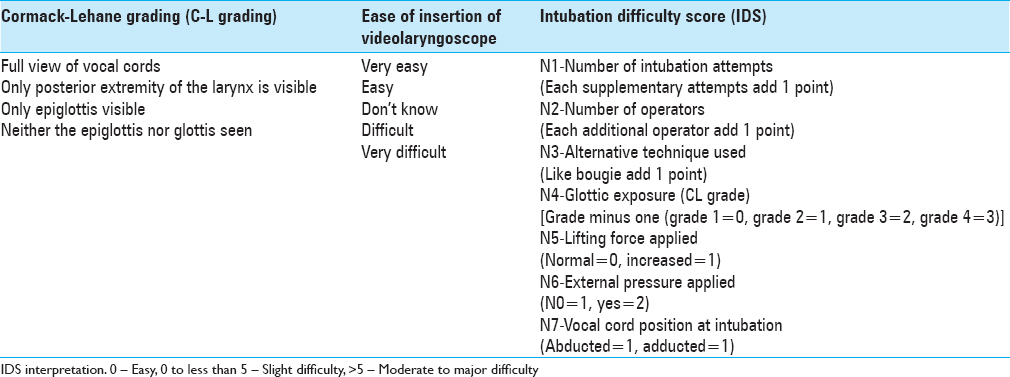

Methods:After standard induction of anesthesia, 135 patients were randomized into three groups: group C (conventional C-MAC videolaryngoscope), group K (King Vision videolaryngoscope), and group D (D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscope). Cervical immobilization was maintained with Manual in line stabilization with anterior part of cervical collar removed. First pass intubation success, time for intubation, and glottic visualization (Cormack – Lehane grade and percentage of glottic opening) were noted. Intubation difficulty score (IDS) was used for grading difficulty of intubation. Five-point Likert scale was used for ease of insertion of laryngoscope.

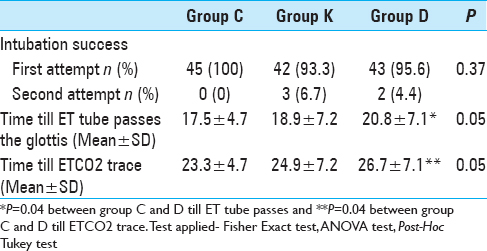

Results:First attempt success rate were 100% (45/45), 93.3% (42/45), and 95.6% (43/45) in patients using conventional C-MAC, King Vision, and D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscopes, respectively. Time for intubation in seconds was significantly faster with conventional C-MAC videolaryngoscope (23.3 ± 4.7) compared to D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscope (26.7 ± 7.1), whereas conventional C-MAC and King Vision were comparable (24.9 ± 7.2). Good grade glottic visualization was obtained with all the three videolaryngoscopes.

Conclusion:All the videolaryngoscopes provided good glottic visualization and first attempt success rate. Conventional C-MAC insertion was significantly easier. We conclude that all the three videolaryngoscopes can be used effectively in patients with cervical spine injury.

Keywords: Cervical spine immobilization, glottic visualization, videolaryngoscopes

INTRODUCTION

Although direct laryngoscopy has been used with variable success, it has the potential to cause greater cervical spine movement.[

The C-MAC (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) is a portable videolaryngoscope, which has similar curvature as standard Mac Intosh (C blade) and a more angulated D blade. The King Vision Videolaryngoscope (KVVL) (King Systems, Noblesville, IN, USA) is one of the new indirect laryngoscope with channeled and nonchanneled blades. KVVL has a unique design, and high quality image can prove useful in cervical spine injury patients without movement of the neck. This study compared the C-MAC (both conventional and D blade) and KVVL in patients with proven/suspected cervical spine injury on cervical immobilization in terms of first attempt intubation success, laryngoscopic view, and time for intubation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

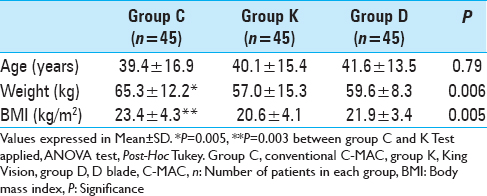

Approval for the study was obtained form the Institute ethics committee (project no: JIP/IEC/2014/8/365 (CTRI/2015/06/005936); and all patients signed an informed written consent. The study included adults, aged 18–60 years, with 1–2 grade American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status and proven or suspected cervical spine injury. All were placed in cervical spine immobilization/rigid cervical collars, and scheduled for elective surgery to be performed under general anesthesia. A total of 135 patients were randomized into 3 groups (45 each): Group K (nonchanneled blade of King Vision), group C (conventional blade of C-MAC), and group D (D blade of C-MAC) was used for endotracheal intubation.

Pre-oxygenation with 100% O2 for 3 min was done with rigid cervical collar in place. All the patients were induced with 2 µg/kg of Fentanyl, 2 mg/kg of Propofol, and muscle relaxation was achieved with 0.1 mg/kg of Vecuronium. Patients were ventilated with Isoflurane (2%) in oxygen using circle absorber system. Just before laryngoscopy, anterior part of the hard cervical collar was removed, and the spine immobilization was maintained using MILS by an assistant anesthesiologist. All the intubations were performed (as per the manufacturer recommendations) by an experienced anesthesiologist, who had done at least 30 intubations, with each device. All standard PVC-made endotracheal tube (ET tube) 8.0 was used for males and size 7.0 for females. The ET tube was pre-shaped to the shape of C type, D type, or King Vision blade using a rigid stylet.

Parameters studied

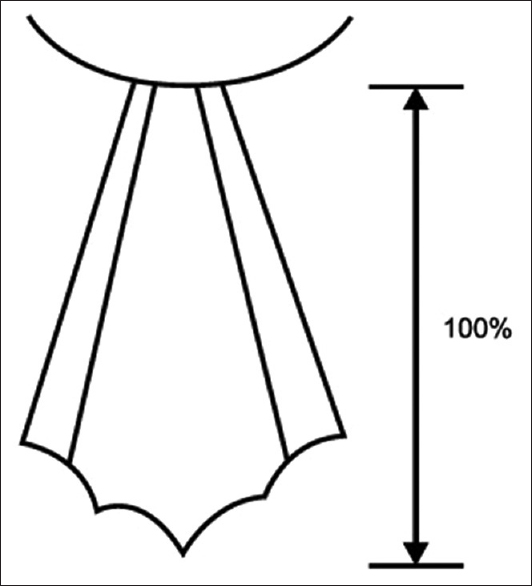

The laryngeal view was assessed using Cormack – Lehane grade (CL grade) [

Statistical methods

Statistical testing was conducted with statistical package for the social science system SPSS version 16.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Results on continuous measurements are presented on Mean ± SD (Min–Max) and results on categorical measurements are presented in Number (%). Significance is assessed at 5% level of significance. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) has been used to find the significance of study parameters between three or more groups of patients, Post-Hoc Tukey test has been employed to find the pairwise significance between groups. Chi-square/Fisher Exact test has been used to find the significance of study parameters on categorical scale between two or more groups.

RESULTS

All three groups were comparable with respect to age [

Visualization of the glottis

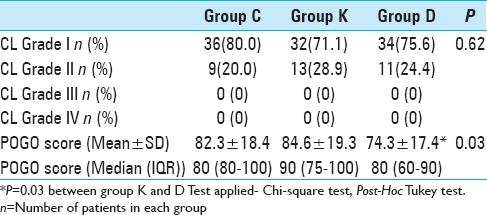

Cormack–Lehane grading and POGO scores were used for visualizing the glottis. Good grade visualization (CL grade 1 and 2) of the vocal cords was obtained in all the patients in three groups [

Glottis view is also assessed using POGO score. The mean POGO scores were comparable in group C and group K [

Success of intubation

Intubation was successful in all patients (100%), using all three devices [

Time for intubation

Times for passing of VL through incisors to visualization of passing of ET tube through glottis and also for appearance of ETCO2 tracing were noted with these devices [

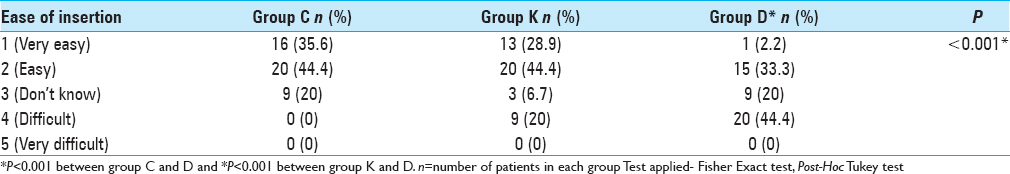

Ease of insertion of laryngoscope

The curvatures of laryngoscope blades are different with King Vision and C and D blades of C-MAC devices. Hence ease of insertion was noted based on 5 point Likert scale [

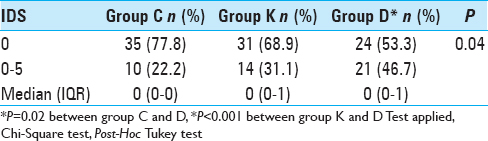

Intubation difficulty score

An IDS indicates the degree of difficulty of intubation. IDS scores were comparable in group C and group K (P = 0.34) [

Alternative techniques used

Only few patients required laryngeal manueuver (2, 3, and 5 in group C, K, and D, respectively) for aiding the passage of the endotracheal tube (ET) through glottic opening (P > 0.05). In one patient in group K, bougie assisted endotracheal tube insertion was done.

Complications

One patient in group K had bronchospasm, following ET tube insertion and was managed according to our institute protocol.

DISCUSSION

In patients with cervical spine injury with cervical immobilization, endotracheal intubation by direct laryngoscope is difficult due to poor visualization of glottis. In these scenarios, where alignment of oropharyngeal and laryngeal axes is not possible, indirect laryngoscopes such as videolaryngoscopes play a vital role in providing optimal glottis view, without movement of cervical spine. Though C-MAC conventional blade and D blades have been used in simulated difficult airway scenarios with cervical immobilization,[

The available literature for use of videolaryngoscope is in simulated difficult airway scenarios such as, hard collar or MILS maneuver in patients with normal airways or as a teaching/testing material on manikins.[

Optimal visualization of the glottis is important for the success of intubation with nil/restricted spine mobility. In our study, CL grade 1 visualization was obtained in 36 (80%), 32 (72%), 34 (76%) patients with conventional C-MAC, KVVL, and D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscope, respectively. A good grade of glottis visualization (CL grade 1 and 2) was obtained in all patients. In a manikin-based study with cervical immobilization by Kılıçaslan et al., good grade view (CL grade 1 and 2) was obtained by all the laryngoscopists.[

The CL grading system has numerous problems. The grades are ambigious between grade 1 and grade 2.[

Success of intubation

Better visualization of the glottis does not necessarily imply improved first attempt success of endotracheal intubation using VL owing to unique curvature of the blades. We used styleted ET tube, preshaped to the blade of particular VL for better visualization of the tip of the ET tube. First attempt success was noted in 100% (45/45), 93.3% (42/45), 95.6% (43/45) of the patients using conventional blade C-MAC, KVVL, and D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscopes, respectively [

The prolonged apnea time and delayed intubation can lead to hypoxemia and desaturation in patients. Because the tube was visualized passing through the glottis, we measured both the times; (a) time from scope insertion to tube passing the glottis and (b) time from scope insertion to appearance of first ETCO2 tracing on the monitor. The mean intubation times were comparable in conventional C-MAC and KVVL (23 vs. 24 s) and KVVL and D blade C-MAC (24 vs. 26 s) [

One of the prerequisites for the successful laryngoscopy and subsequent intubation in patients with cervical immobilization is ease of insertion of laryngoscope blade. We graded the ease of insertion of laryngoscope blade as 1 to 5 (1, very easy to 5, very difficult). The ease of insertion of conventional C-MAC was significantly better as compared to KVVL and D blade C-MAC VL [

The factors which determine difficulty of intubation are number of attempts, number of operators, alternative technique used, glottis exposure, application of lifting force external pressure, and the vocal cord position. The intubation difficulty score[

Limitations

In the present study, all the patients were intubated after induction of general anesthesia with MILS. Therefore, no post intubation neurologic assessment was done to know the effectiveness of these devices in preventing further neurological injury due to laryngoscopy and intubation.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, King Vision videolaryngoscopy, conventional C-MAC, and D blades were assessed for first attempt success of intubation, time for intubation, and glottic visualization.

We conclude,

All the three videolaryngoscopes provided good first attempt intubation success Intubation times were faster with conventional C-MAC as compared to D blade of C-MAC. King Vision videolaryngoscope and conventional C-MAC had comparable intubation time All the three videolaryngoscopes provided good grade glottic visualization The ease of insertion of laryngoscope blade is graded as conventional C- MAC > King Vision > D blade C-MAC videolaryngoscopes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Plaisance P. The intubation difficulty scale (IDS): Proposal and evaluation of a new score characterizing the complexity of endotracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1997. 87: 1290-7

2. Akihisa Y, Maruyama K, Koyama Y, Yamada R, Ogura A, Andoh T. Comparison of intubation performance between the King Vision and Macintosh laryngoscopes in novice personnel: A randomized, crossover manikin study. J Anesth. 2014. 28: 51-7

3. Alvis BD, Hester D, Watson D, Higgins M, St Jacques P. Randomized controlled trial comparing the McGrath MAC video laryngoscope with the King Vision video laryngoscope in adult patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016. 82: 30-5

4. Aziz MF, Dillman D, Fu R, Brambrink AM. Comparative effectiveness of the C-MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy in the setting of the predicted difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2012. 116: 629-36

5. Cattano D, Ferrario L, Patel CB, Maddukuri V, Melnikov V, Gumbert SD. Utilization of C-MAC videolaryngoscopy for direct and indirect assisted endotracheal intubation. J Anesthesiol Clin Sci. 2013. 2: 10-

6. Cook TM. A grading system for direct laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1999. 54: 496-7

7. Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984. 39: 1105-11

8. Hastings RH, Kelley SD. Neurologic deterioration associated with airway management in a cervical spine-injured patient. Anesthesiology. 1993. 78: 580-3

9. Heath KJ. The effect of laryngoscopy of different cervical spine immobilisation techniques. Anaesthesia. 1994. 49: 843-5

10. Jain D, Dhankar M, Wig J, Jain A. Comparison of the conventional CMAC and the D-blade CMAC with the direct laryngoscopes in simulated cervical spine injury-a manikin study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2014. 64: 269-74

11. Kılıçaslan A, Topal A, Erol A, Uzun ST. Comparison of the C-MAC D-Blade, Conventional C-MAC, and Macintosh Laryngoscopes in Simulated Easy and Difficult Airways. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2014. 42: 182-9

12. Levitan RM, Ochroch EA, Kush S, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Assessment of airway visualization: Validation of the percentage of glottic opening (POGO) scale. Acad Emerg Med. 1998. 5: 919-23

13. McElwain J, Laffey JG. Comparison of the C-MAC®, Airtraq®, and Macintosh laryngoscopes in patients undergoing tracheal intubation with cervical spine immobilization. Br J Anaesth. 2011. 107: 258-64

14. Murphy LD, Kovacs GJ, Reardon PM, Law JA. Comparison of the king vision video laryngoscope with the macintosh laryngoscope. J Emerg Med. 2014. 47: 239-46

15. Murthy TV, Bhatia P, Gogna RL, Prabhakar T. Airway management: Uncleared cervical spine Injury. Indian J Neurotrauma IJNT. 2005. 2: 99-101

16. Ng I, Hill AL, Williams DL, Lee K, Segal R. Randomized controlled trial comparing the McGrath videolaryngoscope with the C-MAC videolaryngoscope in intubating adult patients with potential difficult airways. Br J Anaesth. 2012. 109: 439-43

17. Sarvaiya N, Thakur D, Tendolkar B. A comparative study of endotracheal intubation as per intubation difficulty score, using Airtraq and McCoy laryngoscopes with manual-in-line axial stabilization of cervical spine in adult patients. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016. p. 3211-8

18. Seo SH, Lee JG, Yu SB, Kim DS, Ryu SJ, Kim KH. Predictors of difficult intubation defined by the intubation difficulty scale (IDS): Predictive value of 7 airway assessment factors. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012. 63: 491-7

19. Shah SB, Hariharan U, Bhargava AK. C Mac D blade: Clinical tips and tricks. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2016. 6: 6-10

20. Siriussawakul A, Limpawattana P. A validation study of the intubation difficulty scale for obese patients. J Clin Anesth. 2016. 33: 86-91

21. Yentis SM, Lee DJ. Evaluation of an improved scoring system for the grading of direct laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1998. 53: 1041-4