- Department of Neurosurgery, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

- Department of Neurosurgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India

Correspondence Address:

Nupur Pruthi

Department of Neurosurgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India

DOI:10.4103/sni.sni_110_18

Copyright: © 2018 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Nupur Pruthi, Lokesh S. Nehete. Use of intraoperative X-ray to differentiate between reducible versus irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation. 18-Jun-2018;9:121

How to cite this URL: Nupur Pruthi, Lokesh S. Nehete. Use of intraoperative X-ray to differentiate between reducible versus irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation. 18-Jun-2018;9:121. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/use-of-intraoperative-x%e2%80%91ray-to-differentiate-between-reducible-versus-irreducible-atlantoaxial-dislocation/

Abstract

Background:The treatment and classification of atlantoaxial dislocations (AADs) remain controversial. Here, we utilized intraoperative X-ray to differentiate between reducible and irreducible AADs.

Methods:Five patients were diagnosed as having irreducible AAD on dynamic and post-traction X-rays. Under general anesthesia, they were placed prone in a neutral position utilizing skeletal traction. The X-rays and motor evoked potential (MEP), were then monitored before, during, and after placing a thumb on the C2 spinous process and pushing it anteriorly to attain reduction.

Results:The intraoperative X-ray confirmed reducibility of AAD in four patients; they subsequently underwent a C1–C2 posterior fusion, which maintained that reduction. For the one patient with an irreducible AAD (despite thumb maneuver), an anterior release was required first to attain reduction, followed by posterior C1–C2 fusion.

Conclusion:Here, we divided irreducible AAD into two categories: a) reducible—utilizing a thumb maneuver to compress/push the C2 spinous process forward with the patient positioned prone and b) irreducible—those who cannot be reduced with this technique. A posterior only approach was sufficient for those with “reducible” AAD, whereas those who could not be reduced required an anterior release followed by posterior fusion.

Keywords: Anterior release, dynamic X-ray, irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD), posterior cervical surgery, push-prone maneuver, thumb maneuver, traction

INTRODUCTION

The treatment and classification of atlantoaxial dislocations (AADs) remain controversial. It is generally accepted that the treatment of symptomatic AAD should include surgical reduction and fusion/fixation.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

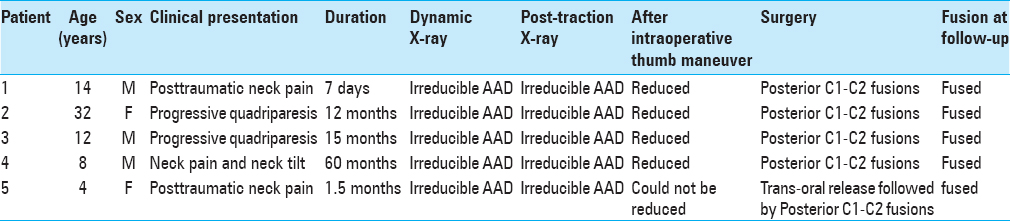

Five patients were diagnosed as having irreducible AAD based on preoperative dynamic and post-traction X-rays [

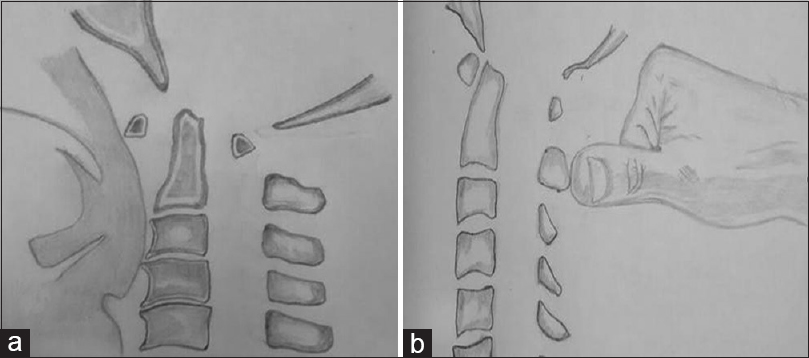

After general anesthesia, patients were placed in a prone neutral position utilizing with skeletal traction, X-ray, and MEP monitoring. They then underwent a reduction by applying posterior thumb pressure, compressing the C2 spinous process anteriorly [

RESULTS

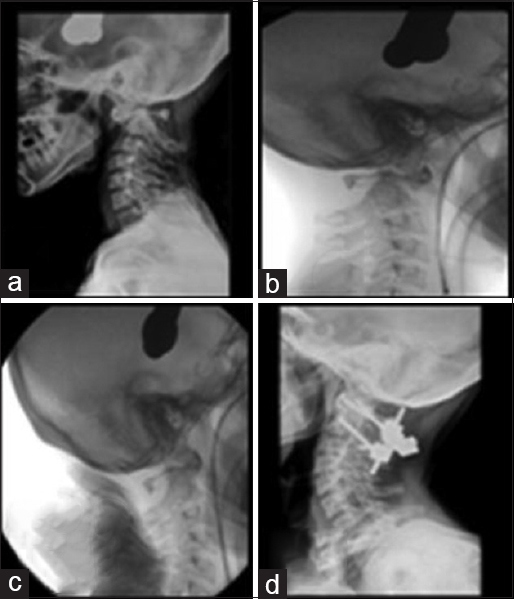

Full reduction of AAD with or without associated odontoid fractures, was successfully achieved and maintained in four patients; all four successfully underwent posterior C1–C2 fusions [Figures

Figure 2

Case 1 atlantoaxial dislocation (AAD) without fracture: (a) preoperative X-ray showing irreducible ADD in flexion, (b) preoperative X-ray showing irreducible ADD in extension, (c) post-traction X-ray showing irreducible AAD, (d) midsagittal computed tomography spine showing AAD with canal narrowing, (e) Magnetic Resonance Imaging cervical spine showing canal narrowing at C1 with obliteration of anterior CSF spaces, (f) intraoperative X-ray after position under general anesthesia before thumb maneuver showing AAD, (g) intraoperative X-ray after position under general anesthesia after thumb maneuver showing reduction of AAD, (h) postoperative implant in situ with reduction of AAD

Figure 3

Case 2 AAD with odontoid fracture: (a) preoperative X-ray showing odontoid fracture with AAD, (b) intraoperative X-ray after positioning under general anesthesia before thumb maneuver showing AAD, (c) intraoperative X-ray after positioning under general anesthesia after thumb maneuver showing reduction of AAD, (d) postoperative X-ray showing implant in situ with reduction of AAD

All patients achieved/maintained correction in spine alignment and bony fusion over a mean follow-up period of 14.4 months (4–23 months).

DISCUSSION

Differentiating between “reducible” and “irreducible” AADs is complicated. It is typically defined utilizing radiological investigations: dynamic and post-traction X-rays. Utilizing X-ray, traction, and MEP monitoring, we proposed utilizing a novel posterior C2 thumb compressive maneuver to differentiate between “reducible” and “irreducible” AADs [

Sharp and Purser described a procedure of manual reduction of atlantoaxial subluxation in patients with atlanto-axial instability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and/or rheumatoid arthritis. The anterior subluxation in the flexed position was reduced by extension and, consequently, increased the space available for the cord.[

“Reducible” AAD requires posterior fusion alone whereas an “irreducible” AAD requires an anterior transoral decompression/release followed by a posterior fusion.[

CONCLUSION

Here, we defined irreducible AAD into two categories: a) reducible—those for whom posterior-anterior C2 thumb maneuvers resulted in adequate reduction requiring posterior fusion alone and b) irreducible despite the thumb maneuver, warranting initial anterior release followed by posterior fusion.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Goel A, Kulkarni AG, Sharma P. Reduction of fixed atlantoaxial dislocation in 24 cases: Technical note. JNeurosurg Spine. 2005. 2: 505-9

2. Menezes AH. Decision making. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008. 24: 1147-53

3. Srivastava SK, Aggarwal RA, Nemade PS, Bhosale SK. Single-stage anterior release and posterior instrumented fusion for irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation with basilar invagination. Spine. 2016. 16: 1-9

4. Uitvlugt G, Indenbaum S. Clinical assessment of atlantoaxial instability using the Sharp-Purser test. Arthritis Rheum. 1988. 31: 918-22

5. Wang C, Yan M, Zhou HT, Wang SL, Dang GT. Open reduction of irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation by transoral anterior atlantoaxial release and posterior internal fixation. Spine. 2006. 31: E306-313