- Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka, Japan.

Correspondence Address:

Ryo Miyaoka, Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_707_2023

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Yoshimi Shinohara, Ryo Miyaoka, Junkoh Yamamoto. Surgical strategy for intracranial hemorrhage with accidental hypothermia in elderly individuals. 05-Jan-2024;15:3

How to cite this URL: Yoshimi Shinohara, Ryo Miyaoka, Junkoh Yamamoto. Surgical strategy for intracranial hemorrhage with accidental hypothermia in elderly individuals. 05-Jan-2024;15:3. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12697

Abstract

Background: Accidental hypothermia poses a significant threat to the elderly, and its prevalence might increase due to aging and increasing isolation of individuals in Japan. Here, a series of four consecutive cases of accidental hypothermia in elderly patients with intracranial hemorrhage who underwent surgical treatment at our institution is presented.

Case Description: All patients were admitted to the emergency department with a diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage. Among them, two patients experienced acute circulatory failure during emergency surgery, necessitating immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Two other patients required intensive care before surgery; however, one of them exhibited signs of impending cerebral herniation, requiring emergency surgery.

Conclusion: Accidental hypothermia poses a significant threat to elderly individuals, carrying a substantial mortality risk and demanding intensive general care. During rewarming, careful considerations must be devoted to potential complications, such as ventricular fibrillation, rewarming shock, bleeding diathesis, and hyperkalemia. Despite these risks, many life-threatening cases necessitate emergency surgery and rewarming procedures in parallel. The formulation of a surgical strategy aimed at mitigating rewarming-related complications should be entrusted to anesthesiologists. Strict follow-up is required to increase intracranial pressure when prioritizing intensive care over surgery.

Keywords: Accidental hypothermia, Critical care, Geriatrics, Intracerebral hemorrhage, Intracranial hemorrhage, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Accidental hypothermia is a major condition affecting elderly individuals. Approximately 50% of all deaths attributed to hypothermia occur in elderly individuals aged >65 years.[

In this report, four reports of surgical interventions for intracranial hemorrhage with accidental hypothermia in the elderly have been outlined, along with a discussion on its clinical management with a literature review.

CASE PRESENTATION

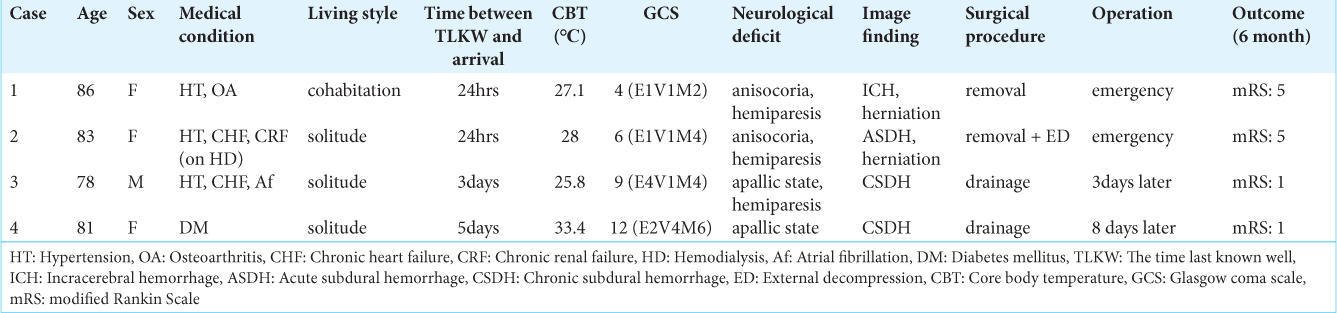

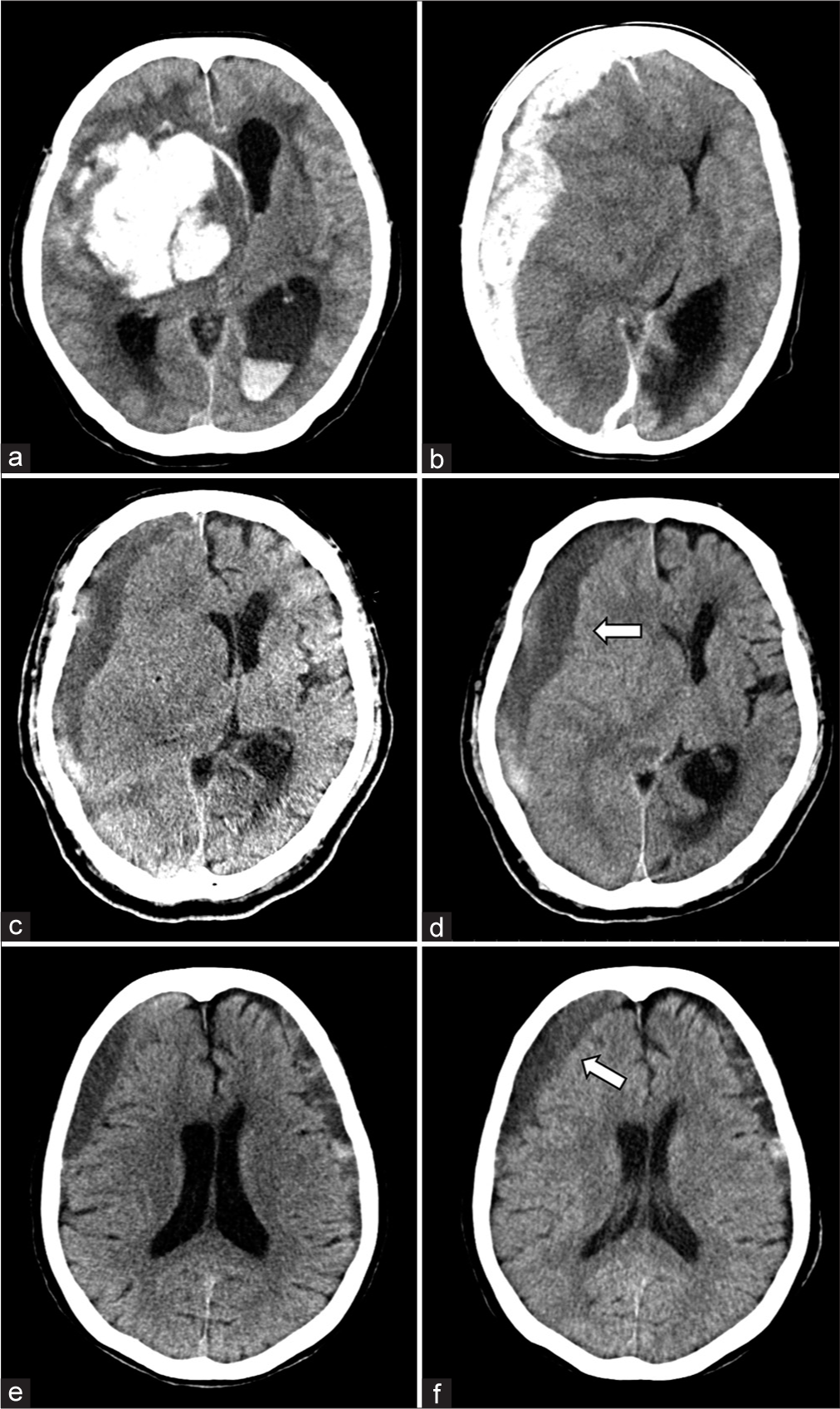

We report the four consecutive cases of accidental hypothermia with intracranial hemorrhage that required surgical treatment at our institution [

Case 1 was of an independent 85-year-old woman living with her son. She was discovered lying outdoors on her premises and was subsequently transported by ambulance. Her last documented well-being was tracked back to 24 hours earlier. On arrival, her condition indicated hypothermia (core body temperature [CBT] of 27.1°C; heart rate [HR] of 90 beats/min; and blood pressure [BP] of 173/119 mmHg), coupled with a neurological deficit (Glasgow coma scale [GCS] score at 4/15; anisocoria; and quadriplegia). Electrocardiography (ECG) confirmed the presence of J waves and a prolonged Q wave T wave interval. Head computed tomography (CT) revealed a hemorrhage in the right putamen with imminent cerebral herniation [

Figure 1:

Imaging findings of patients who developed hypothermia with intracranial hemorrhage. (a) Axial non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) demonstrating a large acute intracerebral hematoma in the right putamen with imminent cerebral herniation. (b) Axial non-contrast head CT demonstrating a large acute subdural hematoma in the right hemisphere with imminent cerebral herniation. (c) Axial non-contrast head CT demonstrating a chronic subdural hematoma in the right hemisphere with a severe mass effect. (d) Follow-up imaging showed increased hematoma volume and mass effect. The white arrow indicates an increase in hematoma volume. (e) Axial non-contrast head CT demonstrating chronic subdural hematomas in both hemispheres with a mild mass effect. (f) Follow-up imaging showed an increased volume of the right subdural hematoma and a mass effect. The white arrow indicates blurriness of the sulcus due to the mass effect.

Case 2 was of an independent 83-year-old woman leading a solitary lifestyle. She had chronic renal failure and was undergoing hemodialysis. She was discovered lying at her residence and was transported to the emergency department. Her last documented well-being was tracked back to 24 hours prior. On evaluation, she exhibited hypothermia (CBT, 28.0°C; HR, 52 beats/min; BP, 145/72 mmHg), coupled with a neurological deficit (GCS score, 6/15; anisocoria; and hemiplegia). Head CT revealed a right acute subdural hematoma with imminent cerebral herniation [

Case 3 was of an independent 78-year-old man who was discovered collapsed in his bathroom and subsequently transported to the emergency department. His last documented well-being was traced back 3–4 days earlier. On assessment, he presented hypothermia (CBT, 25.8°C; HR, 66 beats/min; BP, 124/48 mmHg) with a neurological deficit (GCS score, 9/15; left hemiplegia). Head CT revealed a right subacute subdural hematoma with a midline shift of 18 mm [

Case 4 was of an independent 81-year-old woman living alone who was discovered lying at her residence and subsequently transported to the emergency department. Her last documented well-being was tracked back to 5 days earlier. On arrival, she presented hypothermia (CBT, 33.0°C; HR, 98 beats/min; BP, 134/49 mmHg) with a neurological deficit (GCS score, 14/15; no paresis). Head CT revealed chronic bilateral subdural hematomas [

DISCUSSION

Accidental hypothermia is defined as an inadvertent reduction in CBT to below 35°C. Severity categorizations of accidental hypothermia are as follows: mild when CBT ranges between 35°C and 32°C, moderate when CBT ranges between 32°C and 30°C, and severe when CBT is below 30°C.[

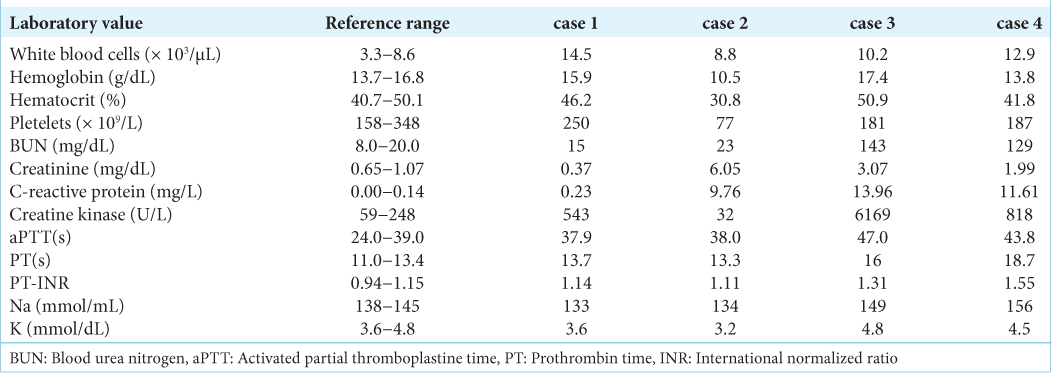

Hypothermia results in several physiological abnormalities, including dehydration, coagulopathy, electrolyte disturbances, respiratory failure, and cardiac dysfunction. As the severity of hypothermia increases, the cases of severe organ damage and fatality also increase.[

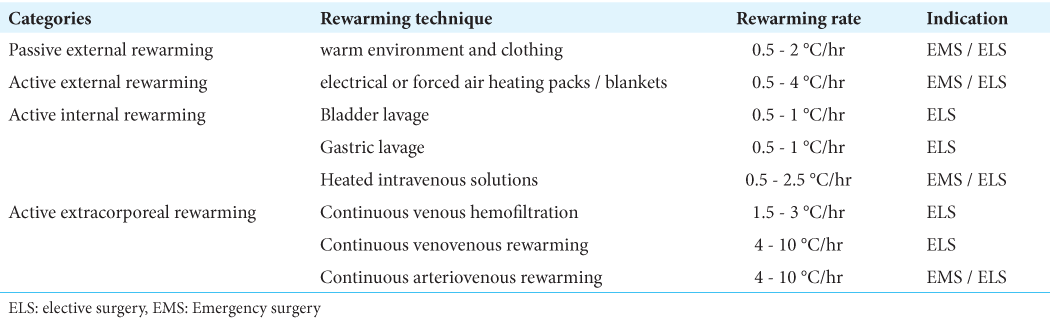

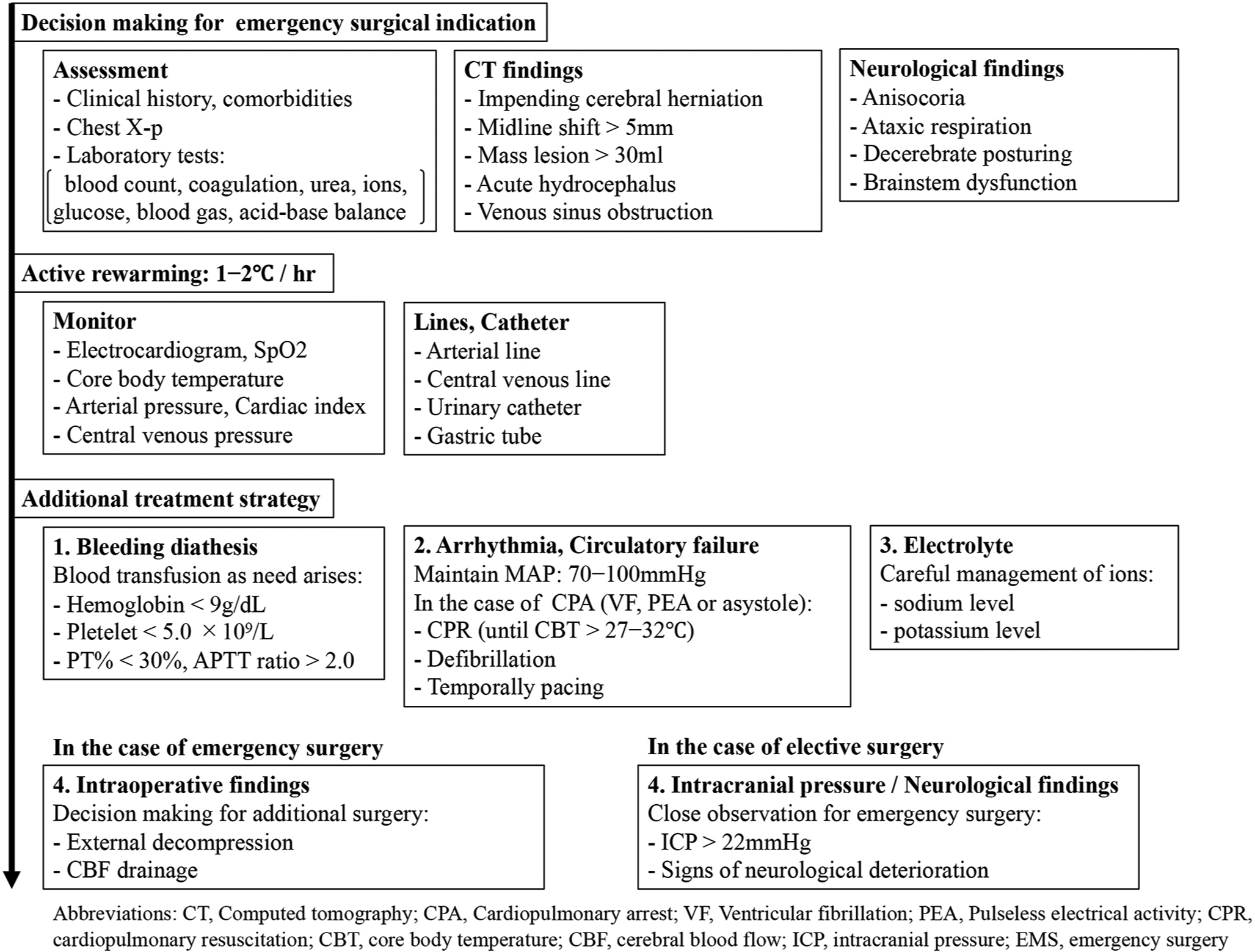

Given the prognosis of accidental hypothermia, prioritizing surgery for rewarming in cases of intracranial hemorrhage with accidental hypothermia is not advisable. First, surgical indications should be based on a comprehensive assessment of initial clinical symptoms and head CT findings. When a patient has acute hemorrhagic components and exhibits findings indicative of impending cerebral herniation, prompt emergency surgery should be performed concurrently with rewarming. However, it is crucial to remain vigilant about the potential complications associated with rewarming when dealing with emergency surgery. Adequate preparation for CPR is essential, particularly in cases of acute circulatory failure, when defibrillation or pharmacological interventions might yield no effect on severe hypothermia. In addition, low potassium levels in the blood might induce lethal arrhythmias; however, such levels can rapidly rebound with rewarming, potentially escalating the risk factor of critical hyperkalemia with ARF. Considering these complications, a central venous route should be established to facilitate active internal rewarming, enable prompt emergency hemodialysis, and allow for a large infusion in cases involving acute circulatory failure. Therefore, high-risk cases require multidisciplinary care, and effective collaboration with anesthesiologists is essential. In cases involving elective surgery, attention should be paid to the rapid deterioration of neurological symptoms due to increasing ICP associated with rewarming. Therefore, gradual rewarming and close observation using imaging and neurological monitoring should be performed.

In each of these cases, the interval between the most recent documented well-being and transportation was 24 hours. The context of societies characterized by a solitary lifestyle and advancing age could contribute to the development of accidental hypothermia among the elderly population. Given this demographic, it becomes imperative to revisit the strategies for the clinical management of intracranial hemorrhage with accidental hypothermia.

CONCLUSION

Herein, four consecutive cases of accidental hypothermia with intracranial hemorrhage in elderly patients have been reported. When addressing accidental hypothermia within the elderly population, it becomes imperative to entertain the possibility of intracranial hemorrhage. In the treatment setting, determining the indication for surgery according to neurological and imaging findings is essential. In the case of emergency surgery, due diligence must be exercised to mitigate the complications associated with rewarming. In the case of elective surgery, strict follow-up observations should be performed with attention to increasing ICP.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Avellanas ML, Ricart A, Botella J, Mengelle F, Soteras I, Veres T. Management of severe accidental hypothermia. Med Intens. 2012. 36: 200-12

2. Clifton GL, Miller ER, Choi SC, Levin HS, McCauley S, Smith KR. Hypothermia on admission in patients with severe brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002. 19: 293-301

3. Danzl DF, Pozos RS, Auerbach PS, Glazer S, Goetz W, Johnson E. Multicenter hypothermia survey. Ann Emerg Med. 1987. 16: 1042-55

4. Danzl DF. Hypothermia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002. 23: 57-68

5. Fujiwara N, Shimada N, Nojima M, Ariyoshi K, Sawada N, Iwasaki M. Exploratory research on determinants of place of death in a large-scale cohort study: The JPHC study. J Epidemiol. 2023. 33: 120-6

6. Holzer M, Behringer W, Schörkhuber W, Zeiner A, Sterz F, Laggner AN. Mild hypothermia and outcome after CPR. Hypothermia for Cardiac Arrest (HACA) Study Group. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997. 111: 55-8

7. Kempainen RR, Brunette DD. The evaluation and management of accidental hypothermia. Respir Care. 2004. 49: 192-205

8. Kinoshita K, Utagawa A, Ebihara T, Furukawa M, Sakurai A, Noda A. Rewarming following accidental hypothermia in patients with acute subdural hematoma: Case report. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006. 96: 44-7

9. Kollmar R, Staykov D, Dörfler A, Schellinger PD, Schwab S, Bardutzky J. Hypothermia reduces perihemorrhagic edema after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010. 41: 1684-9

10. Lewis SR, Evans DJ, Butler AR, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Alderson P. Hypothermia for traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. 9: CD001048

11. Melmed KR, Lyden PD. Meta-analysis of pre-clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia for intracerebral hemorrhage. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2017. 7: 141-6

12. Naito H, Isotani E, Callaway CW, Hagioka S, Morimoto N. Intracranial pressure increases during rewarming period after mild therapeutic hypothermia in postcardiac arrest patients. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2016. 6: 189-93

13. Oommen SS, Menon V. Hypothermia after cardiac arrest: Beneficial, but slow to be adopted. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011. 78: 441-8

14. Peterson K, Carson S, Carney N. Hypothermia treatment for traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2008. 25: 62-71

15. Petrone P, Asensio JA, Marini CP. Management of accidental hypothermia and cold injury. Curr Probl Surg. 2014. 51: 417-31

16. Statistics Bureau of Jap, editors. The statistical handbook of Japan 2023. Ch. 02. Japan: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2023. p. 32-82

17. Steiner T, Friede T, Aschoff A, Schellinger PD, Schwab S, Hacke W. Effect and feasibility of controlled rewarming after moderate hypothermia in stroke patients with malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery. Stroke. 2001. 32: 2833-5

18. Winkelmann M, Soechtig W, Macke C, Schroeter C, Clausen JD, Zeckey C. Accidental hypothermia as an independent risk factor of poor neurological outcome in older multiply injured patients with severe traumatic brain injury: A matched pair analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019. 45: 255-61

19. Yokota Y. The clinical characteristics of hypothermic patients in the winter of Japan-the final report of hypothermia study 2011. J Jpn Assoc Acute Med. 2013. 24: 377-89 (Japanese)