- Department of Neurosurgery, Institute of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Mito Kyodo General Hospital, Tsukuba University Hospital, Mito Area Medical Education Center, Mito, Ibaraki, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Southern Tohoku Hospital, Koriyama, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Tsukuba Memorial Hospital, Tsukuba, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tsukuba Hospital, Tsukuba, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

- Department of Neurosurgery, Dokkyo Medical University, Mibu, Japan

Correspondence Address:

Shinya Watanabe, Institute of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_148_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Shinya Watanabe1,2, Masaaki Yamamoto3, Hitoshi Aiyama4, Narushi Sugii5, Masahide Matsuda6, Hiroyoshi Akutsu7, Eiichi Ishikawa6. A retrospective cohort study of stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: Comparison of two age groups (75 years or older vs. 65–74 years). 26-Jul-2024;15:257

How to cite this URL: Shinya Watanabe1,2, Masaaki Yamamoto3, Hitoshi Aiyama4, Narushi Sugii5, Masahide Matsuda6, Hiroyoshi Akutsu7, Eiichi Ishikawa6. A retrospective cohort study of stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: Comparison of two age groups (75 years or older vs. 65–74 years). 26-Jul-2024;15:257. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13013

Abstract

Background: Treatment outcome data of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for vestibular schwannomas (VS) in patients ≥75 years (late elderly) are lacking. Approximately 39% of patients ≥75 years with VS were reported to experience severe facial palsy after surgical removal. This study compared the treatment outcomes post-SRS for VS between patients ≥75 and 65–74 years (early elderly).

Methods: Of 453 patients who underwent gamma knife SRS for VS, 156 were ≥65 years old. The late and early elderly groups comprised 35 and 121 patients, respectively. The median tumor volume was 4.4 cc, and the median radiation dose was 12.0 Gy.

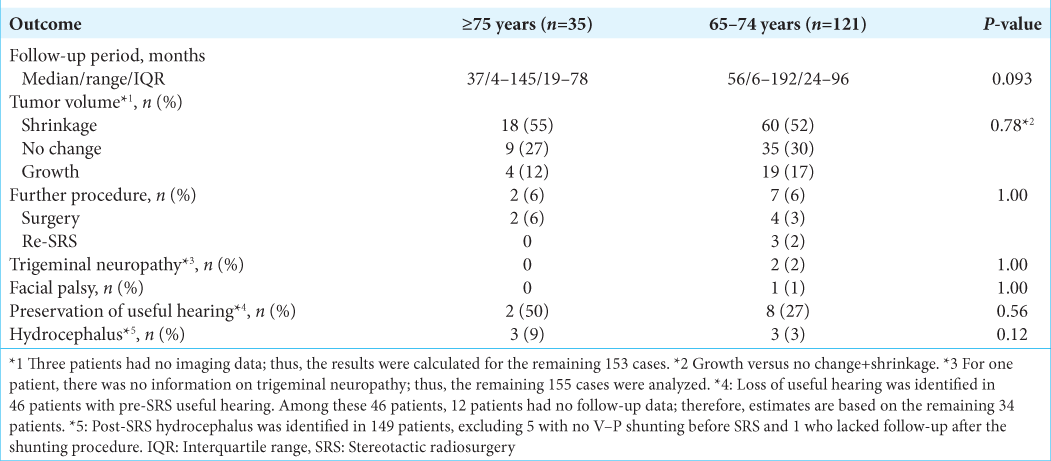

Results: The median follow-up periods were 37 and 56 months in the late and early elderly groups, respectively. Tumor volume control was observed in 27 (88%) and 95 (83%) patients (P = 0.78), while additional procedures were required in 2 (6%) and 6 (6%) patients (P = 1.00) in the late and early elderly groups, respectively. At the 60th and 120th months post-SRS, the cumulative tumor control rates were 87%, 75%, 85%, and 73% (P = 0.81), while the cumulative clinical control rates were 93% and 87%, 95%, and 89% (P = 0.80), in the late and early elderly groups, respectively. In the early elderly group, two patients experienced facial pain, and one experienced facial palsy post-SRS; there were no adverse effects in the late elderly group (both P = 1.00).

Conclusion: SRS is effective for VS and beneficial in patients ≥75 years old as it preserves the facial nerve.

Keywords: Gamma knife, Late elderly, Stereotactic radiosurgery, Tumor control, Vestibular schwannoma

INTRODUCTION

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is widely performed as a primary or postoperative procedure for patients with small-to-medium-sized vestibular schwannomas (VSs).[

In this study, we retrospectively reviewed the long-term treatment outcomes after gamma knife (GK) SRS for SRS between late and early elderly patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient selection

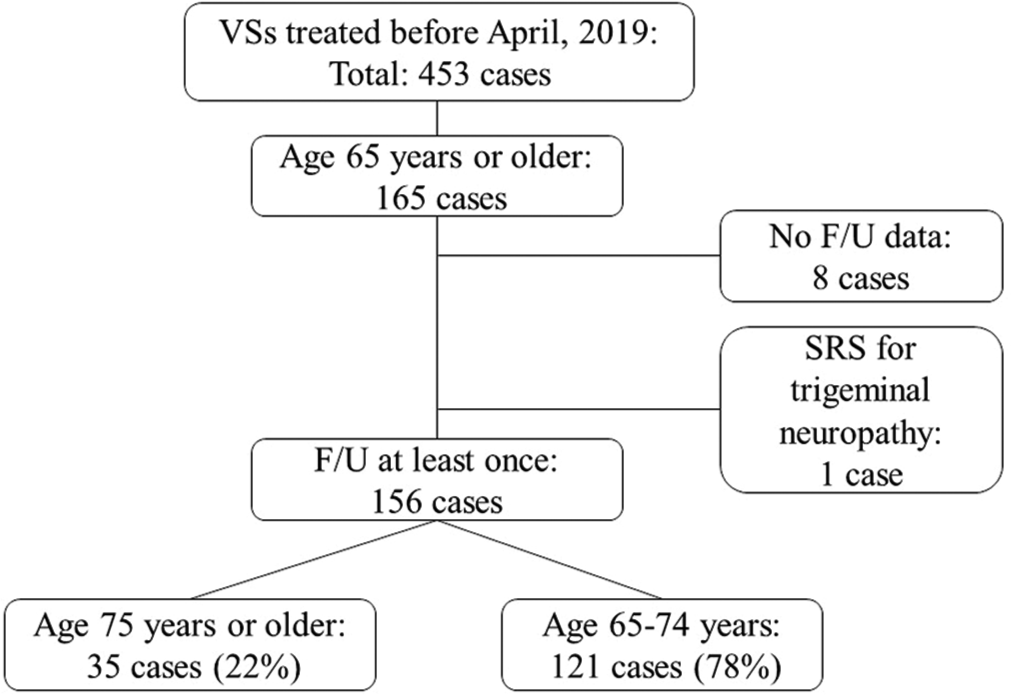

Our institutional review board approved this retrospective cohort study (IRB No. R03-01, May 14th, 2021, University of Tsukuba Hospital), for which we employed our prospectively accumulated database. The database included 453 patients who underwent GK SRS for VS between 1990 and 2019. Among the 453 patients [

The clinical characteristics of the 156 patients studied are summarized in

Radiosurgical technique

Radiosurgery was performed according to the method outlined in a previous study.[

Dose planning was executed through a Leksell GammaPlan system (Elekta Instrument AB).

Post-SRS follow-up

In a prior publication,[

Clinical outcomes

In assessing tumor growth control, we anticipated measurement errors of 25% for volume and 10% for diameter estimation. A volume ≥125% and/or a diameter ≥110% compared with baseline values indicated “growth,” while a volume ≤75% and/or a diameter ≤90% indicated “shrinkage.” Any other observations were considered as “no change.” Clinical tumor control was characterized by the absence of further procedures (FP), such as salvage tumor removal or restereotactic radiosurgery (re-SRS). FP-free survival time was defined as the duration between SRS and the day of salvage surgery/re-SRS or the latest follow-up. The determination of FP considered not only an increased tumor volume but also a patient’s inability to tolerate symptom progression. In assessing the endpoint, FP was considered the event, while other outcomes were censored.

For calculating PTA results, the formula PTA = (a + 2b + c)/4 was utilized, where “a,” “b,” and “c” represent threshold levels at 500 Hz, 1,000 Hz, and 2,000 Hz, respectively. Hearing levels were categorized using the Gardner and Robertson system [

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for baseline variables included the use of frequencies and proportions for categorical data, while medians, means, and standard deviations were employed for continuous variables. The cumulative incidences of FP for time-to-event outcomes were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method.[

RESULTS

Tumor control and FP-free interval

The median follow-up periods were 37 (range: 4–145) and 56 (range: 6–192) months in the late and early elderly groups, respectively.

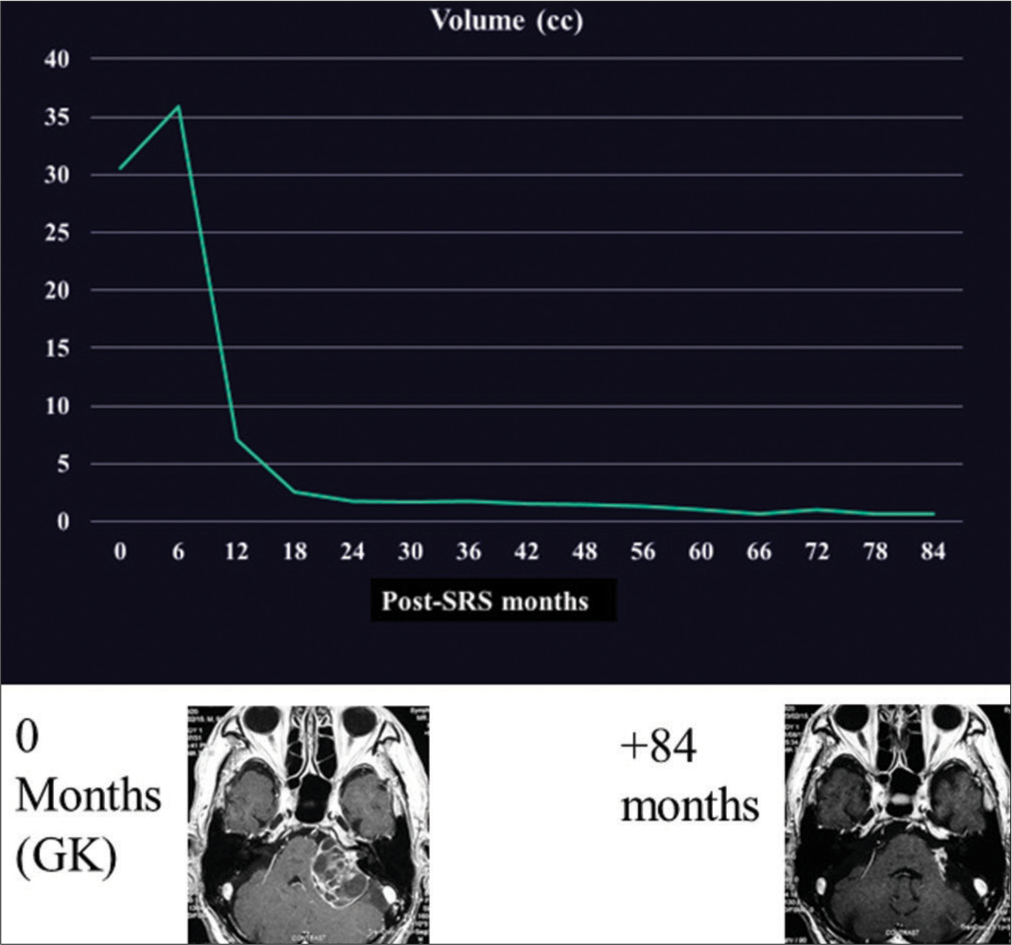

We previously described the case of a 92-year-old man with a large VS.[

Figure 3:

Chronological tumor volume changes of an illustrative case. Age at the time of stereotactic radiosurgery was 91 years old, late elderly. The tumor (30.6 cc) was irradiated with a peripheral dose of 12.0 Gy (maximum dose, 20.0 Gy) and shrunk significantly over the 6–12-month period. GK: Gamma knife, SRS: stereotactic radiosurgery.

Post-SRS functional outcomes

During a median follow-up period of 37 (range: 4–145) and 56 (range: 6–192) months in the late and early elderly groups, trigeminal neuropathy developed in zero and two (2%) patients, respectively. (P = 1.00). Among these two patients in the late elderly, symptoms were well controlled by administering carbamazepine in one patient, whereas symptoms persisted in the other, necessitating nerve block injection and carbamazepine administration. No patient suffered from facial nerve palsy in the late elderly group, whereas one (1%) patient developed facial nerve palsy in the early elderly group (P = 1.00). Among the 46 patients with serviceable hearing pre-SRS, this level of hearing acuity was preserved in two (50%) and eight (27%) patients in the late and early elderly groups, respectively (P = 0.56). Among the 149 patients without pre-SRS shunting, a ventricular– peritoneal shunt had to be placed for the management of symptomatic hydrocephalus in three (9%) patients in each group (P = 0.12).

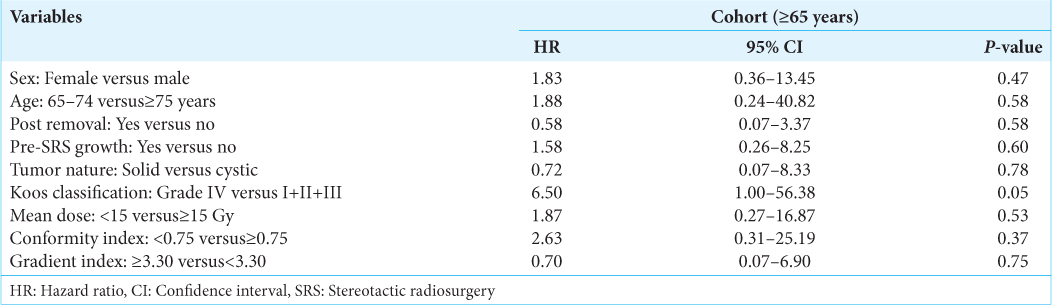

Factors associated with tumor and clinical control

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzed the treatment results of SRS for VS in patients aged ≥75 years compared with those in patients aged 65–74 years. There were no marked differences in the SRS results, including the crude/cumulative tumor control rates, FP-free intervals, hearing preservation rates, and incidences of complications between the two age groups. In the VS in patients ≥75 years cohort, considerably rare cases of facial neuropathy developed than in the existing reports[

Tumor and clinical control in late elderly (aged ≥75 years) patients with VS

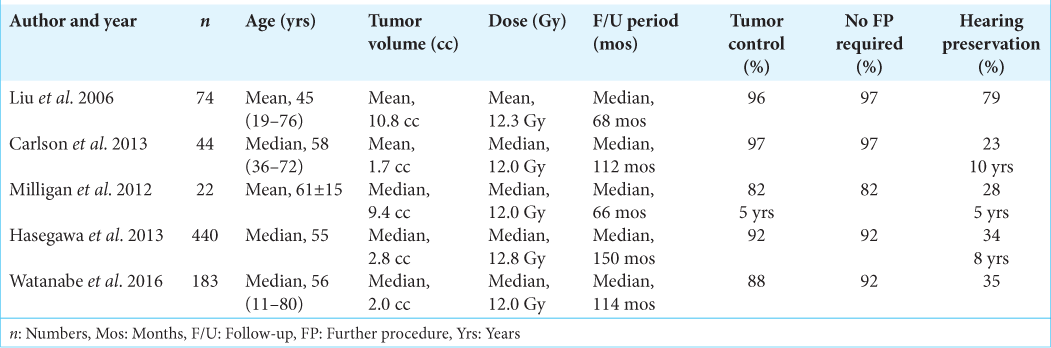

Among the various pre-SRS clinical factors and radiosurgical parameters, advanced age was not considered in previous studies, i.e., previous studies included younger patients; the mean or median age of the study cohort was 45–61 years [

Facial nerve preservation of SRS in late elderly (aged ≥75 years) patients with VS

Post-SRS preservation rates of facial nerve functions are 95–100% at the 5th post-SRS year.[

Weaknesses of our study

The major weakness of our study might be its retrospective design. In addition, clinical factors are heterogeneous; there was some disproportion between the two age groups in terms of both tumor volume and PTA. However, these imbalances were minimal and acceptable. Another weakness is that the late elderly group had a shorter follow-up period than the early elderly group, which may be because the late elderly tended to die earlier or were lost to follow-up due to various causes. Another possible weakness of this study is the lack of meticulous neuro-otological examination results before and after SRS. Ideally, hearing functions should be evaluated using both PTA and the speech discrimination score (SDS). Jacob et al. reported that SDS is significantly correlated with the time to nonserviceable hearing.[

CONCLUSION

When compared with patients with VS aged 65–74 years, SRS is an effective treatment option for VS in patients aged ≥75 years in terms of both long-term tumor control and post-SRS complication rates. SRS in late elderly patients may be more beneficial than surgical removal with respect to facial nerve preservation. Further studies are needed to draw more robust conclusions.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Tsukuba Hospital, number R03-01, dated 14 May 2021.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Aiyama H, Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Watanabe S, Koiso T, Sato Y. Clinical significance of conformity index and gradient index in patients undergoing stereotactic radiosurgery for a single metastatic tumor. J Neurosurg. 2018. 129: 103-10

2. Carlson ML, Jacob JT, Pollock BE, Neff BA, Tombers NM, Driscoll CL. Long-term hearing outcomes following stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: Patterns of hearing loss and variables influencing audiometric decline. J Neurosurg. 2013. 118: 579-87

3. Chopra R, Kondziolka D, Niranjan A, Lunsford LD, Flickinger JC. Long-term follow-up of acoustic schwannoma radiosurgery with marginal tumor doses of 12 to 13 Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007. 68: 845-51

4. Friedman WA, Bradshaw P, Myers A, Bova FJ. Linear accelerator radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas. J Neurolsurg. 2006. 105: 655-61

5. Gardner G, Robertson JH. Hearing preservation in unilateral acoustic neuroma surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988. 97: 55-66

6. Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006. 166: 418-23

7. Hasegawa T, Kida Y, Kato T, Iizuka H, Kuramitsu S, Yamamoto T. Long-term safety and efficacy of stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: Evaluation of 440 patients more than 10 years after treatment with gamma knife surgery. J Neurosurg. 2013. 118: 557-65

8. Hayhurst C, Monsalves E, Bernstein M, Gentili F, Heydarian M, Tsao M. Predicting nonauditory adverse radiation effects following radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: A volume and dosimetric analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012. 82: 2041-6

9. Helal A, Graffeo CS, Perry A, Van Abel KM, Carlson ML, Neff BA. Differential impact of advanced age on clinical outcomes after vestibular schwannoma resection in the very elderly: Cohort study. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2021. 21: 104-10

10. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985. 93: 146-7

11. Jacob JT, Carlson ML, Schiefer TK, Pollock BE, Driscoll CL, Link MJ. Significance of cochlear dose in the radiosurgical treatment of vestibular schwannoma: Controversies and unanswered questions. Neurosurgery. 2014. 74: 466-74

12. Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958. 53: 457-81

13. Kimitsuki T, Matsumoto N, Shibata S, Tamae A, Ohashi M, Noguchi A. Correlation between the maximum on speech discrimination score and pure-tone threshold. Audiology. 2011. 57: 158-63

14. Koos WT. Criteria for preservation of vestibulocochlear nerve function during microsurgical removal of acoustic neurinomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988. 92: 55-66

15. Litvack ZN, Norén G, Chougule PB, Zheng Z. Preservation of functional hearing after gamma knife surgery for vestibular schwannoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2003. 14: e3

16. Liu D, Xu D, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zheng L. Long-term outcomes after gamma knife surgery for vestibular schwannomas: A 10-year experience. J Neurosurg. 2006. 105: 149-53

17. Milligan BD, Pollock BE, Foote RL, Link MJ. Long-term tumor control and cranial nerve outcomes following γ knife surgery for larger-volume vestibular schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 2012. 116: 598-604

18. Murphy ES, Barnett GH, Vogelbaum MA, Neyman G, Stevens GH, Cohen BH. Long-term outcomes of gamma knife radiosurgery in patients with vestibular schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 2011. 114: 432-40

19. Paddick I. A simple scoring ratio to index the conformity of radiosurgical treatment plans. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2000. 93: 219-22

20. Paddick I, Lippitz B. A simple dose gradient measurement tool to complement the conformity index. J Neurosurg. 2006. 105: 194-201

21. Pollock BE, Link MJ, Foote RL. Failure rate of contemporary low-dose radiosurgical technique for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg. 2009. 111: 840-4

22. Timmer FC, Hanssens PE, Van Haren AE, Van Overbeeke JJ, Mulder JJ, Cremers CW. Follow-up after gamma knife radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: Volumetric and axial control rates. Laryngoscope. 2011. 121: 1359-66

23. Tsao MN, Sahgal A, Xu W, De Salles A, Hayashi M, Levivier M. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma: International stereotactic radiosurgery society (ISRS) practice guideline. J Radiosurg SBRT. 2017. 5: 5-24

24. Watanabe S, Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Koiso T, Aiyama H, Kasuya H. Long-term follow-up results of stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas larger than 8 cc. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019. 161: 1457-65

25. Watanabe S, Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Koiso T, Yamamoto T, Matsumura A. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: Average 10-year follow-up results focusing on long-term hearing preservation. J Neurosurg. 2016. 125: 64-72

26. Yamamoto M, Serizawa T, Sato Y, Higuchi Y, Kasuya H, Barfod BE. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: A retrospective cohort study comparing treatment results between two lung cancer patient age groups, 75 years or older vs 65-74 years. Lung Cancer. 2020. 149: 103-12

27. Yancik R, Ries LA. Cancer in older persons: An international issue in an aging world. Semin Oncol. 2004. 31: 128-36

28. Yang HC, Kano H, Awan NR, Lunsford LD, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC. Gamma knife radiosurgery for larger-volume vestibular schwannomas. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011. 114: 801-7

29. Yang I, Sughrue ME, Han SJ, Fang S, Aranda D, Cheung SW. Facial nerve preservation after vestibular schwannoma gamma knife radiosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2009. 93: 41-8