- Departments of Neurosurgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

- Departments of Ophthalmology, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

Correspondence Address:

Zaid Aljuboori

Departments of Neurosurgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_541_2019

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Zaid Aljuboori, William Burke, Heegok Yeo, Abigail McCallum, Jeremy Clark, Brian Williams. Orbitofrontal approach for the fenestration of a symptomatic sellar arachnoid cyst. 17-Jan-2020;11:10

How to cite this URL: Zaid Aljuboori, William Burke, Heegok Yeo, Abigail McCallum, Jeremy Clark, Brian Williams. Orbitofrontal approach for the fenestration of a symptomatic sellar arachnoid cyst. 17-Jan-2020;11:10. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/9842/

Abstract

Background: Sellar arachnoid cysts (SACs) are rare lesions and incidentally found on brain imaging. The pathophysiology is poorly understood. Some authors suggested that SACs develop as a herniation of arachnoid membrane through the diaphragma sellae followed by cyst formation. Furthermore, Meyer et al. postulated that SACs are formed by splitting of the arachnoid layers. Symptomatic SACs present with headache, visual field deficit, or pituitary dysfunction. The data are limited on the indications and timing for intervention. We present a case of symptomatic SAC that was fenestrated using orbitofrontal approach.

Case Description: A 64-year-old female presented with chronic headaches and blurriness of vision. She was previously diagnosed with diabetes insipidus (DI) that was treated with desmopressin, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain at that time was normal. Later on, she developed severe headaches that were managed medically. A year later, she had an episode of generalized seizure that led to the discovery of SAC on brain MRI. On examination, she had a left-sided monocular temporal hemianopia. The patient underwent an orbitofrontal craniotomy for fenestration of the SAC. At 6-month follow-up, her headaches had significantly improved with the resolution of the visual deficit. In addition, the DI had resolved, and the desmopressin was discontinued.

Conclusion: SACs are rare with no consensus on the indications for surgery. Our experience suggests that fenestration of SAC through transcranial approach is a valid option for patients with visual deficit and/or pituitary dysfunction.

Keywords: Arachnoid, Craniotomy, Cyst, Orbitofrontal, Sella

INTRODUCTION

Sellar arachnoid cysts (SACs) constitute about 3% of all intracranial arachnoid cysts. Their pathophysiology is not well understood, and they are often asymptomatic and found incidentally. There are some reports of symptomatic SACs that required treatment.[

They can easily be identified on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), appear as a cystic lesion within the sella with cerebrospinal fluid signals with no obvious communication with the suprasellar subarachnoid space.[

We present a case of symptomatic SAC that was treated with orbitofrontal craniotomy for cyst fenestration.

CASE REPORT

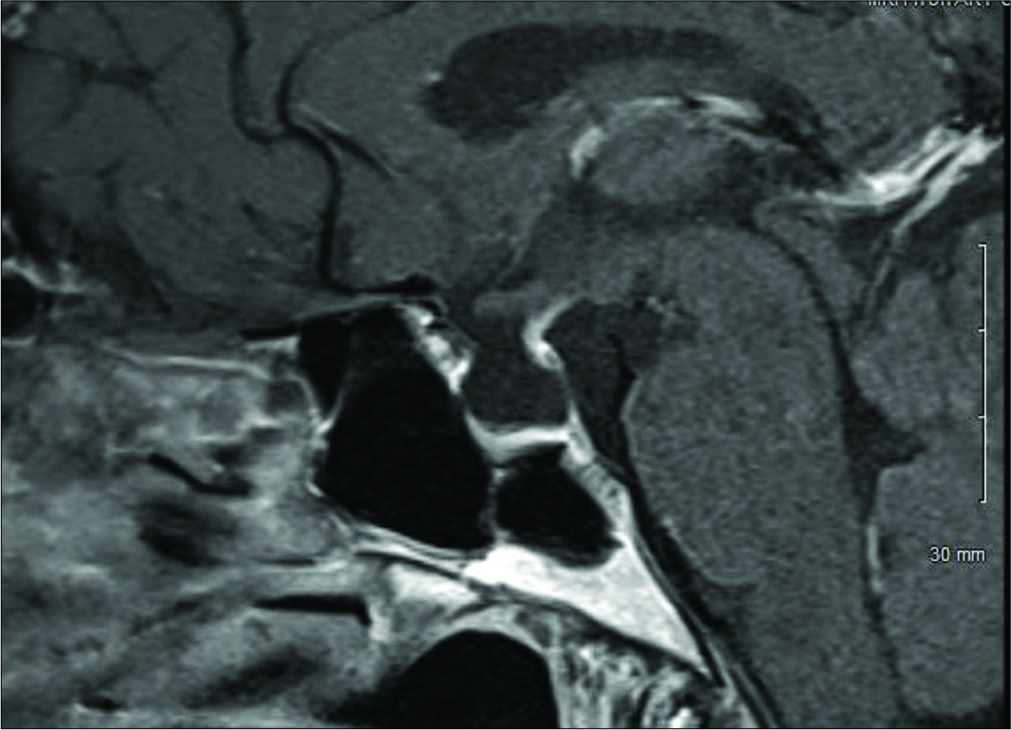

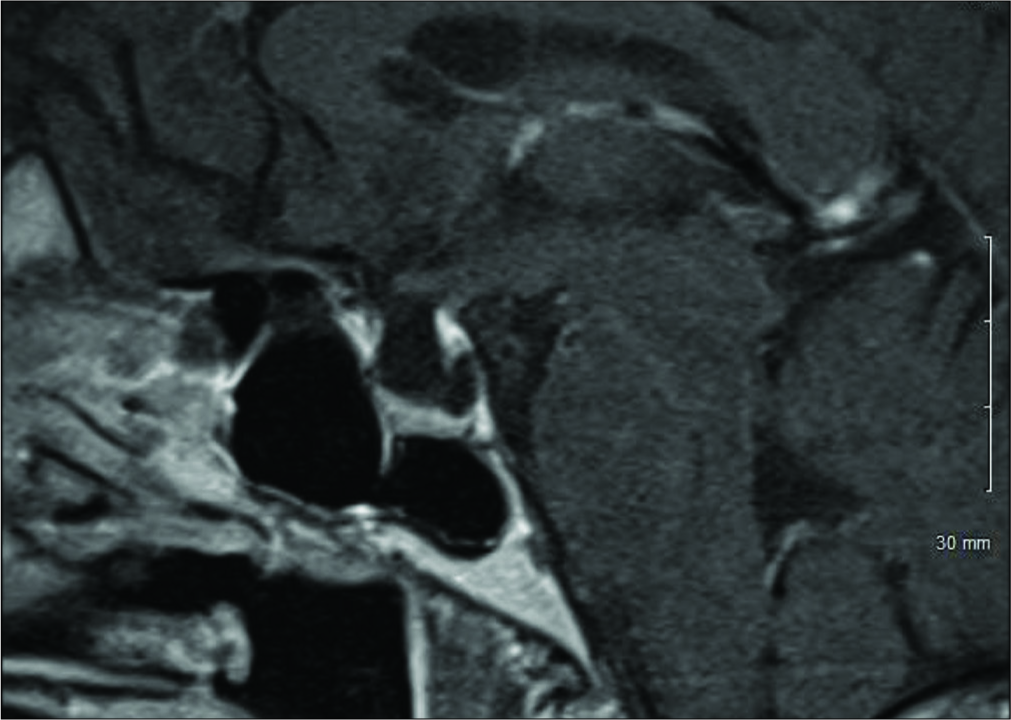

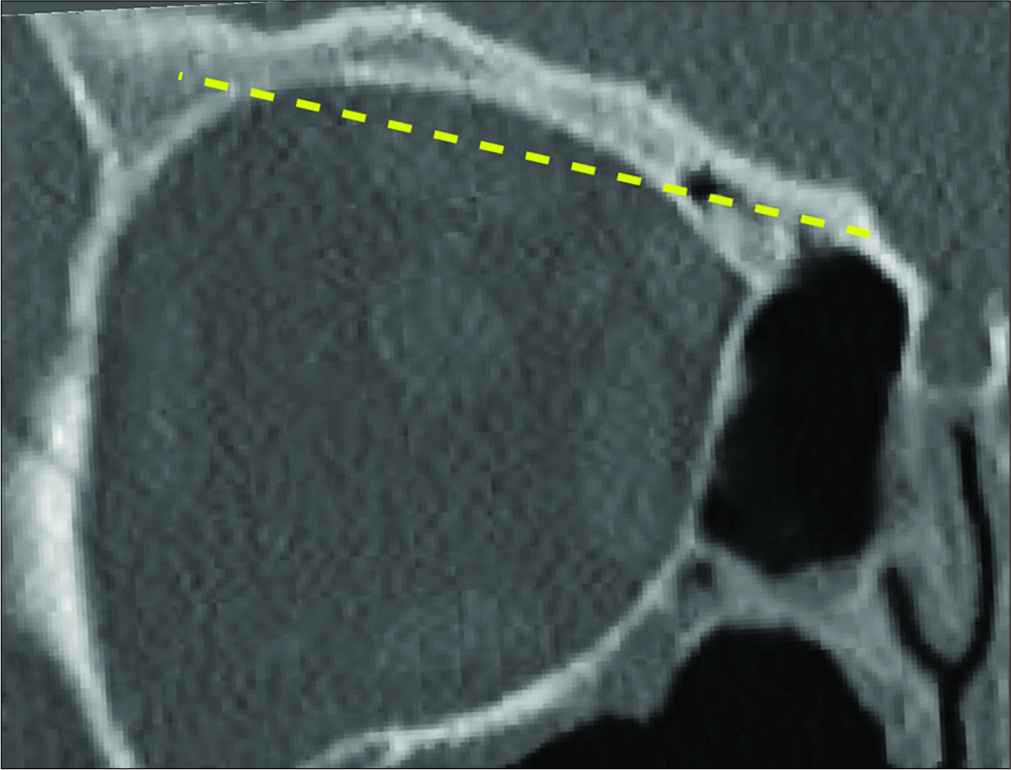

A 64-year-old female presented with chronic severe headaches, blurriness of vision, diabetes insipidus (DI), and an MRI finding of a sellar cystic lesion. She was originally diagnosed with DI at a different institution when she presented with symptoms of polyuria and polydipsia in 2011. At the time, she had a normal MRI of the brain and was treated with desmopressin 100 mcg/day. In 2016, she developed severe, achy bifrontal headaches 2–3 times a week with no associated symptoms. These headaches were managed with ibuprofen and sumatriptan with some benefit. Then, in December 2017, she began experiencing generalized fatigue and blurring of her left-sided vision that caused her to bump into objects on her left side. She also had a single episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure that led to the identification of a new nonenhancing 9.4 × 9.2 × 6.3 mm sellar cystic lesion on MRI of the brain consistent with a SAC [

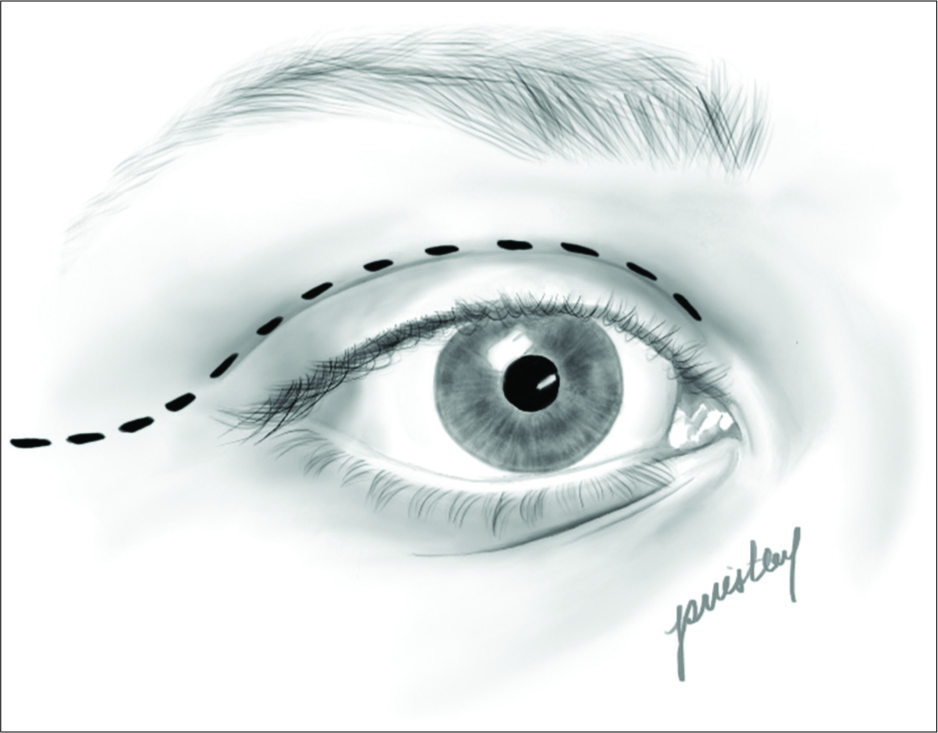

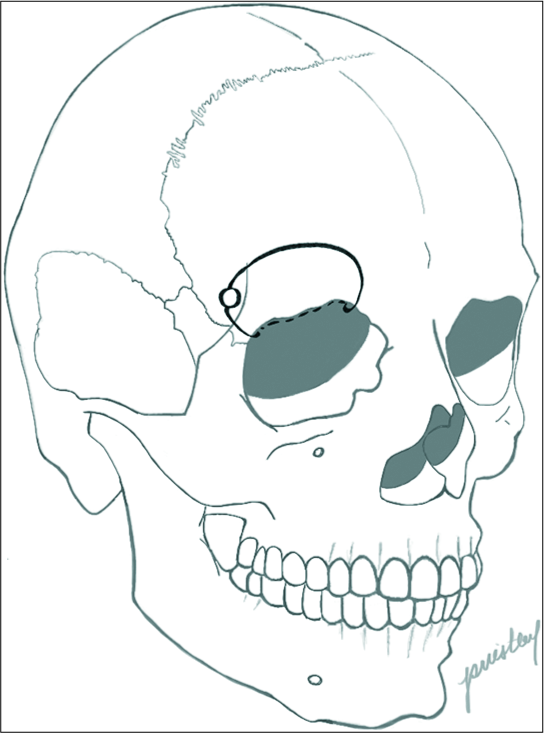

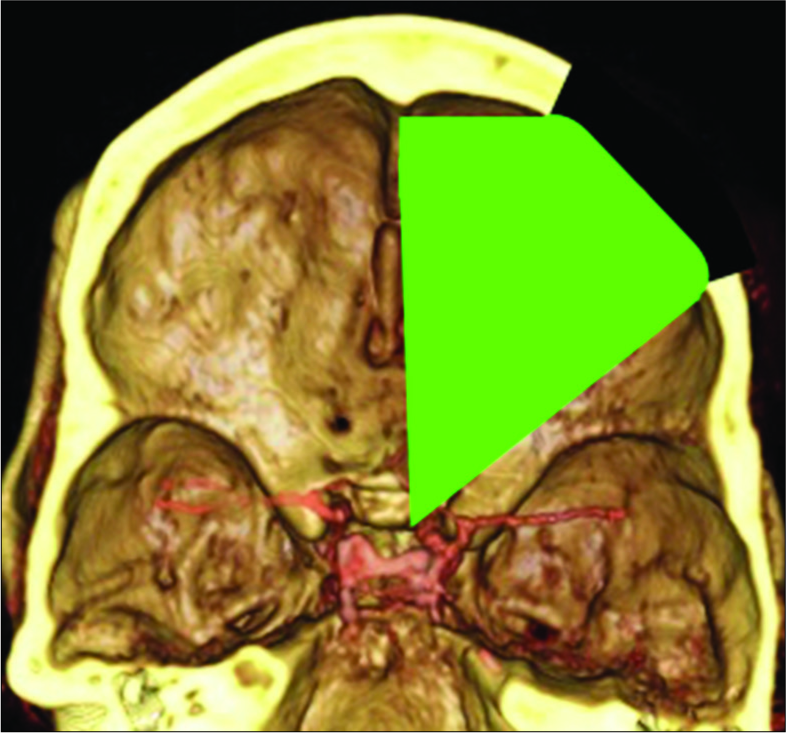

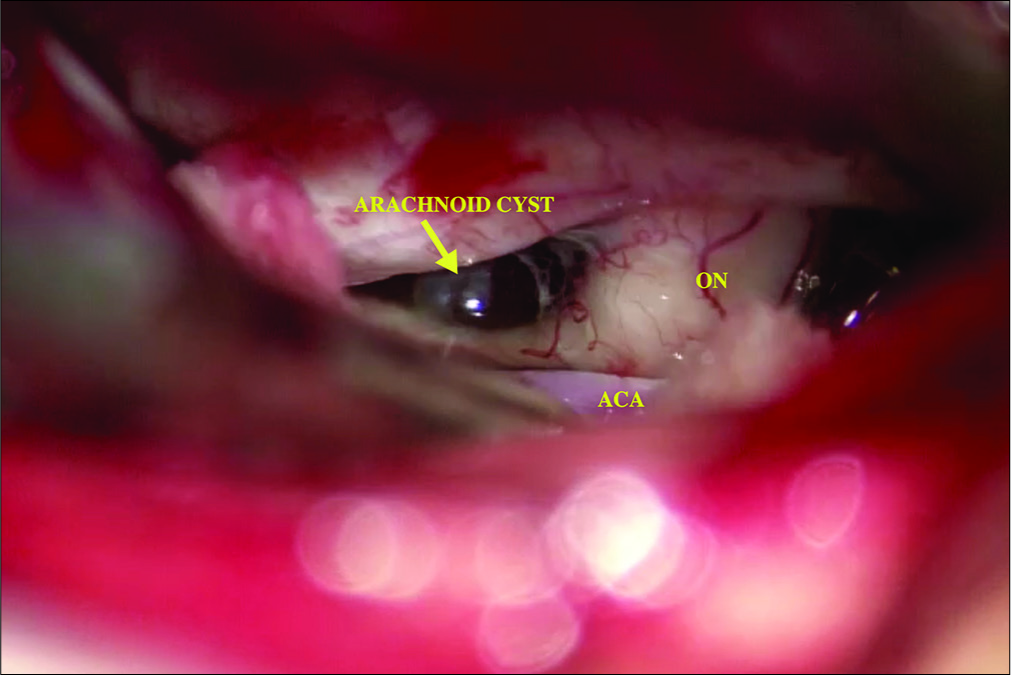

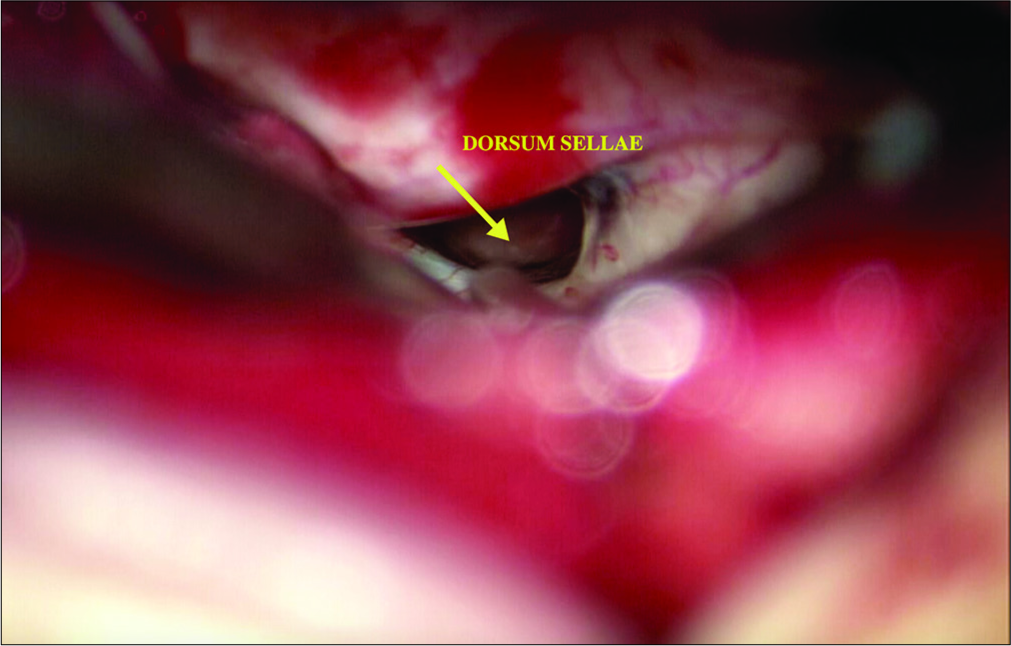

The patient underwent a right-sided orbitofrontal craniotomy for the fenestration of the SAC through an eyelid crease incision [

The patient postoperative course was complicated by a palpebral abscess, which was drained by ophthalmology and treated with oral clindamycin and erythromycin eye drops. At 6-month follow-up, she reported significant improvement of her headaches (1–2 times a month with less severity) with resolution of visual field deficit. In addition, her DI had resolved and was confirmed with laboratory testing and the desmopressin was discontinued by her endocrinologist. Postoperative MRI showed that the cyst was smaller in size with less deformation of the pituitary gland and the stalk [

DISCUSSION

SACs are rare lesions that often found incidentally. They usually treated conservatively with no high-level evidence regarding the indications for surgical intervention. The pathophysiology of SACs is not completely understood. One common theory suggests the development of SACs by a herniation of the basal arachnoid membrane through a defect in diaphragma sellae.[

The goals of surgery for SACs are decompression of the optic apparatus and the pituitary gland. Surgery is rarely indicated to treat headaches. The concept behind the fenestration of the SACs is to create a continuous communication between the cyst and the subarachnoid space. Several surgical approaches have been described to address sellar lesions, they can be grouped into transcranial and transsphenoidal approaches (TSAs). The choice of the optimal approach is affected by multiple factors including the surgeon’s experience, type and size of the lesion, vascular anatomy, and position of the optic chiasm. At present, the endoscopic TSA is the most commonly used approach to treat sellar lesions. SACs represent an exception, due to the increased risk of CSF leak which can be as high as 15–20%.[

CONCLUSION

SACs are rare with unknown etiology, there is a controversy regarding the indications and timing of surgery as well as the optimal surgical approach. Our experience indicates that fenestration of SAC through a transcranial approach is safe and effective surgical option for patients who present with visual deficit and/or pituitary hormonal derangements.

Declaration of patient consent

A patient consent was not obtained as this case report is retrospective in nature with no identifying information of the patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Al-Holou WN, Terman S, Kilburg C, Garton HJ, Muraszko KM, Maher CO. Prevalence and natural history of arachnoid cysts in adults. J Neurosurg. 2013. 118: 222-31

2. Baskin DS, Wilson CB. Transsphenoidal treatment of non-neoplastic intrasellar cysts. A report of 38 cases. J Neurosurg. 1984. 60: 8-13

3. Cavallo LM, Prevedello D, Esposito F, Laws ER, Dusick JR, Messina A. The role of the endoscope in the transsphenoidal management of cystic lesions of the sellar region. Neurosurg Rev. 2008. 31: 55-64

4. Ciric I, Ragin A, Baumgartner C, Pierce D. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: Results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997. 40: 225-36

5. DeBattista JC, Andaluz N, Zuccarello M, Kerr RG, Keller JT. Refining the indications for the addition of orbital osteotomy during anterior cranial base approaches: Morphometric and radiologic study of the anterior cranial base osteology. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2014. 75: e22-6

6. Dubuisson AS, Stevenaert A, Martin DH, Flandroy PP. Intrasellar arachnoid cysts. Neurosurgery. 2007. 61: 505-13

7. Gandy SE, Heier LA. Clinical and magnetic resonance features of primary intracranial arachnoid cysts. Ann Neurol. 1987. 21: 342-8

8. Güdük M, HamitAytar M, Sav A, Berkman Z. Intrasellar arachnoid cyst: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016. 23: 105-8

9. Hayashi Y, Sasagawa Y, Oishi M, Kita D, Misaki K, Fukui I. Contribution of intrasellar pressure elevation to headache manifestation in pituitary adenoma evaluated with intraoperative pressure measurement. Neurosurgery. 2019. 84: 599-606

10. Hornig GW, Zervas NT. Slit defect of the diaphragma sellae with valve effect: Observation of a. “slit valve”. Neurosurgery. 1992. 30: 265-7

11. Iida S, Fujii H, Tanaka Y, Hayashi S, Nagareda T, Moriwaki K. An intrasellar cystic mass and hypopituitarism. Postgrad Med J. 1996. 72: 441-2

12. Iqbal J, Kanaan I, Al Homsi M. Non-neoplastic cystic lesions of the sellar region presentation, diagnosis and management of eight cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999. 141: 389-97

13. Kern E, Laws E, Edward RL.editors. The rationale and technique of selective transsphenoidal microsurgery for the removal of pituitary tumors. Management of Pituitary Adenomas and Related Lesions with Emphasis on Transsphenoidal Microsurgery. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1982. p.

14. Laws ER. Endoscopic surgery for cystic lesions of the pituitary region. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008. 4: 662-3

15. McLaughlin N, Vandergrift A, Ditzel Filho LF, Shahlaie K, Eisenberg AA, Carrau RL. Endonasal management of sellar arachnoid cysts: Simple cyst obliteration technique. J Neurosurg. 2012. 116: 728-40

16. Meyer FB, Carpenter SM, Laws ER. Intrasellar arachnoid cysts. Surg Neurol. 1987. 28: 105-10

17. Miyamoto T, Ebisudani D, Kitamura K, Ohshima T, Horiguchi H, Nagahiro S. Surgical management of symptomatic intrasellar arachnoid cysts--two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1999. 39: 941-5

18. Murakami M, Okumura H, Kakita K. Recurrent intrasellar arachnoid cyst. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003. 43: 312-5

19. Roca E, Penn DL, Safain MG, Burke WT, Castlen JP, Laws ER. Abdominal fat graft for sellar reconstruction: Retrospective outcomes review and technical note. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2019. 16: 667-74

20. Saeki N, Tokunaga H, Hoshi S, Sunada S, Sunami K, Uchino F. Delayed postoperative CSF rhinorrhea of intrasellar arachnoid cyst. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999. 141: 165-9

21. Shim KW, Park EK, Lee YH, Kim SH, Kim DS. Transventricular endoscopic fenestration of intrasellar arachnoid cyst. Neurosurgery. 2013. 72: 520-8

22. Shin JL, Asa SL, Woodhouse LJ, Smyth HS, Ezzat S. Cystic lesions of the pituitary: Clinicopathological features distinguishing craniopharyngioma, rathke’s cleft cyst, and arachnoid cyst. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999. 84: 3972-82

23. Sze G. Diseases of the intracranial meninges: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993. 160: 727-33

24. Thaher F, Hopf N, Hickmann AK, Kurucz P, Bittl M, Henkes H. Supraorbital keyhole approach to the skull base: Evaluation of complications related to CSF fistulas and opened frontal sinus. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2015. 76: 433-7

25. Weil RJ. Rapidly progressive visual loss caused by a sellar arachnoid cyst: reversal with transsphenoidal microsurgery. South Med J. 2001. 94: 1118-21