- Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining, Qinghai Province, China.

Correspondence Address:

Zongyu Xiao, Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, Xining, Qinghai Province, China.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_761_2021

Copyright: © 2021 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Zongyu Xiao. A case report of frontal spontaneous epidural hematoma associated with cranial osteomyelitis and epidural abscess due to paranasal sinusitis. 30-Sep-2021;12:478

How to cite this URL: Zongyu Xiao. A case report of frontal spontaneous epidural hematoma associated with cranial osteomyelitis and epidural abscess due to paranasal sinusitis. 30-Sep-2021;12:478. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11150/

Abstract

Background: Intracranial epidural hematoma (EDH) is frequently secondary to trauma, but in some rare cases, spontaneous EDH (SEDH) could develop without trauma. Cranial osteomyelitis is an uncommon osseous infection that most frequently presents as a postoperative complication but also rarely originates from paranasal sinusitis and can develop extracranially to form a subperiosteal abscess or intracranially to form an epidural, subdural, or cerebral abscess. Intracranial epidural abscess (EDA) is an uncommon infection that forms in the space between the cranial bone and dura mater. It is rare to have a case of SEDH associated with cranial osteomyelitis and EDA due to paranasal sinusitis.

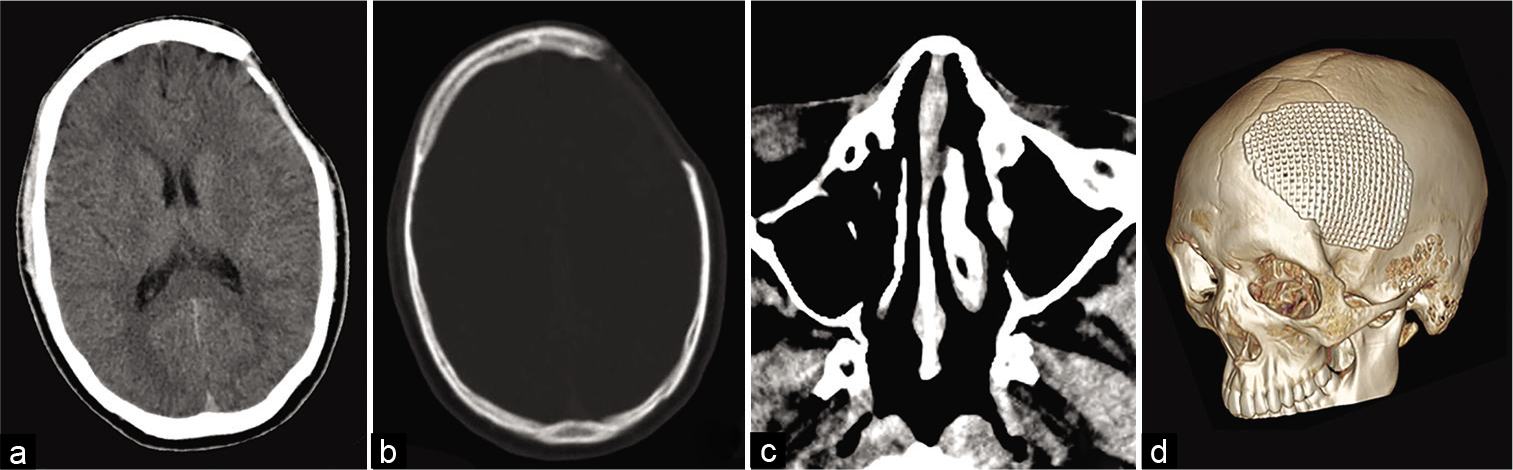

Case Description: An 18-year-old male was admitted to the hospital with headache, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days. The patient denied a history of head trauma, operation, and any other infectious and systemic diseases, and he was not taking any medication. CT scan demonstrated a mixed density lenticular mass with some air collection in the frontal region. The axial sinus CT image demonstrated opacification of the left frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses. An emergency operation confirmed the diagnosis of frontal SEDH associated with EDA and frontal osteomyelitis. The frontal EDH, abscess, and the infected bone were completely removed during the operation without opening the dura. The patient recovered well after receiving 8 weeks of antibiotic therapy, and a cranioplasty was performed 9 months after the craniectomy.

Conclusion: To the best of our knowledge, SEDH associated with EDA is very rare. It is important to recognize the possibility of SEDH associated with cranial osteomyelitis and EDA due to paranasal sinusitis, and the presence of an EDA should, therefore, be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases of SEDH.

Keywords: Cranial osteomyelitis, Epidural abscess, Sinusitis, Spontaneous epidural hematoma

INTRODUCTION

Intracranial epidural hematoma (EDH) commonly occurs as a result of head injury, but in some rare cases, spontaneous EDH (SEDH) can develop without trauma.[

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old male was admitted to the department of neurosurgery on March 14, 2016, with headache, nausea, and vomiting for 2 days. The patient denied a history of head trauma, operation, or any other infectious or systemic diseases, and he was not taking any medication.

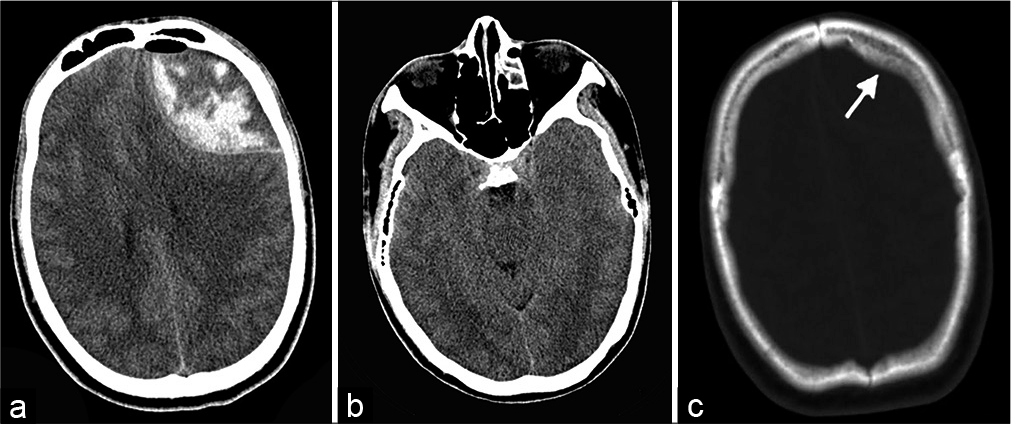

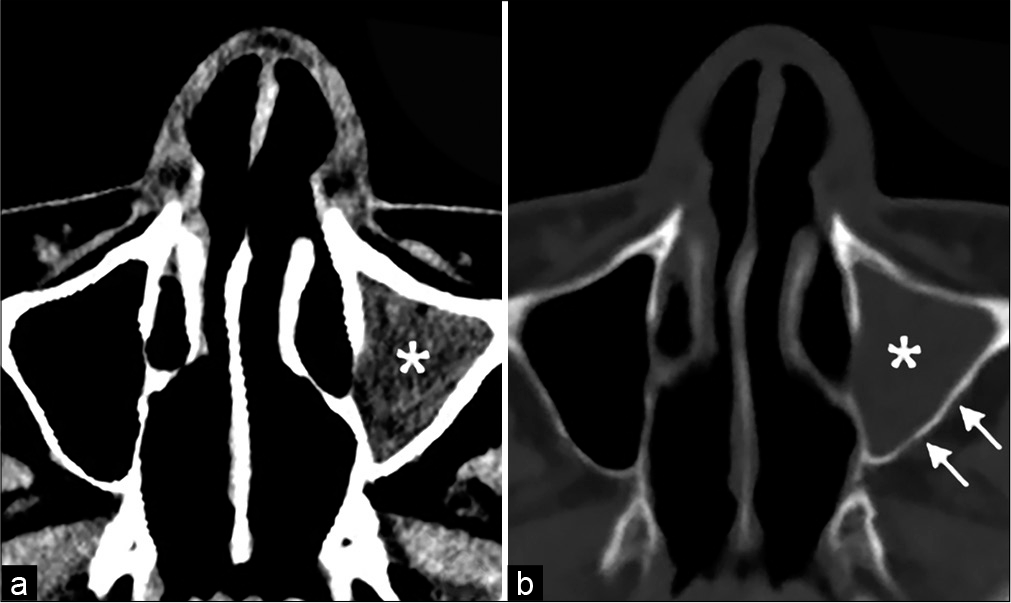

On examination, the patient’s consciousness level according to the Glasgow Coma Scale was E4V4M6, and the patient exhibited confusion, lethargy, and disorientation. There were no meningeal signs or any other neurological deficits. The temperature on admission was 36.8°C, and the blood pressure and laboratory tests were within the normal range. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed a mixed density lenticular mass with some air collection in the left frontal region [

After obtaining informed consent for surgery, an emergency operation was performed. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a supine position, and a left frontotemporal craniotomy was performed. When the first burr hole was made, approximately 50 mL of odorous, thick, yellow pus was removed from the epidural space and bone edge. After elevation of the bone flap, bone was further removed until the normal bone edge was encountered. The infected bone was hypertrophic and soft, and its surface was irregular with some small pores. A fresh EDH beneath the abscess was also found after removal of the EDA, which was carefully evacuated. After abundant irrigation, subdural exploration was deemed unnecessary. The bone flap was discarded. Before closure, the wound was thoroughly washed with povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide, and an epidural drainage tube was placed.

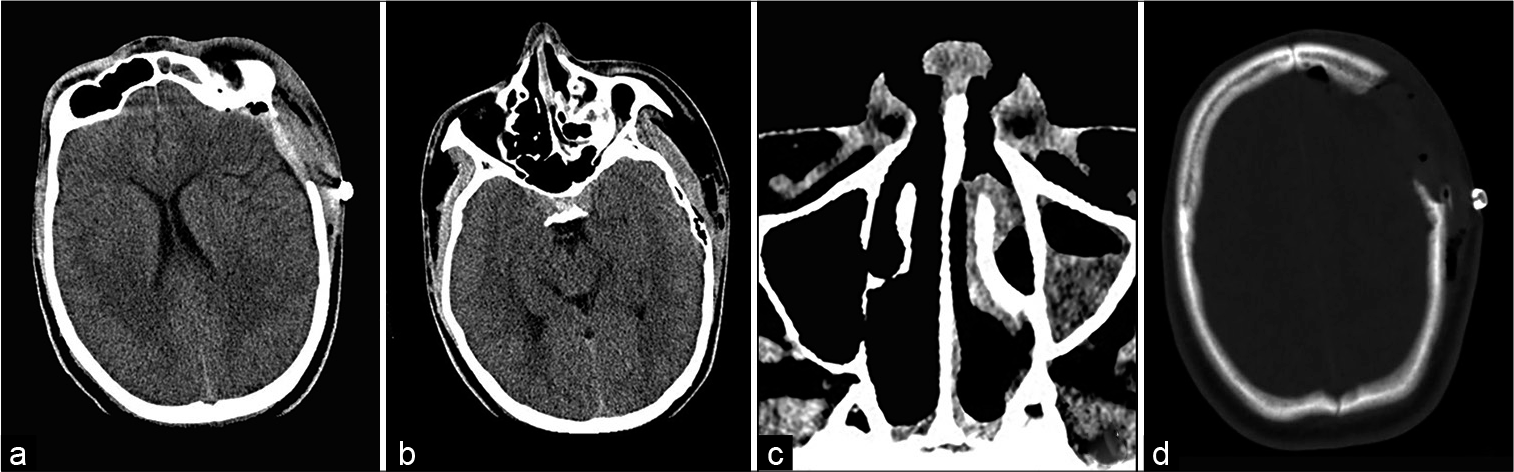

On the 1st day after the operation, a CT scan revealed that the left frontal EDA was removed, with return of the midline and enlargement of the ambient cistern [

Empiric antibiotic therapy (vancomycin 1 g bid combined with metronidazole 500 mg bid) was initiated intravenously for 4 weeks. Postoperatively, the patient’s condition improved with the resolution of symptoms, and he was discharged home 4 weeks later with an indication for 4 more weeks of oral antibiotic therapy (cefixime capsule 100 mg bid). A subsequent CT scan 3 months after surgery showed no signs of infection [

DISCUSSION

EDH is most commonly encountered following head injury, and the majority of cases are associated with skull fractures. However, in some rare cases, EDH can develop without trauma and is called SEDH.[

In general, the classic CT finding of an acute EDH is uniform hyperdensity, but there could also be a mixed density or even low-density appearance due to coagulopathy, serum extruded during the process of clot retraction or CSF leaking into the hematoma.[

The operative and histopathological findings confirmed that the epidural lesion was a frontal SEDH associated with EDA, the preoperative mixed density on CT could be well explained by the coexistence of a hematoma and abscess, and the thickening of the left frontal bone could be well interpreted as cranial osteomyelitis. SEDH, cranial osteomyelitis, and EDA secondary to paranasal sinusitis have each been described previously in the literature separately,[

In this case, we highly suspected that the frontal osteomyelitis and EDA were caused by paranasal sinusitis. At first, the infection developed into osteomyelitis of the surrounding bones, then extended into frontal osteomyelitis, and further developed intracranially to form an EDA; meanwhile, some air could also simultaneously enter the epidural space. Then, the dura may be progressively stripped from the inner table of the skull bone to cause avulsion injury to some meningeal vessels, or the EDA may lead to the infection and subsequent rupture of these meningeal vessels, resulting in EDH development. However, there was still another possibility in this case: the frontal EDH could have formed at first, followed by infection of the hematoma and the accumulation of pus in the epidural space, further resulted in EDA formation and cranial osteomyelitis.[

As the dura protects the brain tissue from the infective material and hematoma, these patients may be asymptomatic or just show symptoms related to the primary paranasal sinusitis, and other neurological symptoms may occur only when the lesion starts to cause a mass effect and increases intracranial pressure. Once a diagnosis of an intracranial abscess is made, the optimal treatment of an EDA requires a combination of surgery and antibiotic therapy, and sometimes drainage of the paranasal sinus is also be needed. Burr hole drainage, craniotomy, and craniectomy are the main surgical methods for EDA, but in this case, craniectomy was necessary due to skull bone osteomyelitis, and the infected necrotic bone needed to be removed during the operation. It is recommended that the dura should not be opened to avoid extending the infection into the subdural space;[

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, SEDH associated with EDA is very rare. It is important to recognize the possibility of SEDH associated with cranial osteomyelitis and EDA due to paranasal sinusitis, and the presence of an EDA should, therefore, be considered in the differential diagnosis of cases of EDH.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of patient consent

Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission obtained for the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Akhaddar A.editors. Cranial Osteomyelitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p.

2. Akhaddar A. Cranial osteomyelitis: The old enemy is back. World Neurosurg. 2018. 115: 475-6

3. Andrabi SM, Sarmast AH, Kirmani AR, Bhat AR. Cranioplasty: Indications, procedures, and outcome An institutional experience. Surg Neurol Int. 2017. 8: 91

4. Chaiyasate S, Halewyck S, Van Rompaey K, Clement P. Spontaneous extradural hematoma as a presentation of sinusitis: Case report and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007. 71: 827-30

5. Clein LJ. Extradural hematoma associated with middle-ear infection. Can Med Assoc J. 1970. 102: 1183-4

6. DeVries S. Metastatic epidural bacterial abscess in a 4-year-old boy. JAMA Neurol. 2013. 70: 648-9

7. Foerster BR, Thurnher MM, Malani PN, Petrou M, CaretsZumelzu F, Sundgren PC. Intracranial infections: Clinical and imaging characteristics. Acta Radiol. 2007. 48: 875-93

8. Griffiths SJ, Jatavallabhula NS, Mitchell RD. Spontaneous extradural haematoma associated with craniofacial infections: Case report and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2002. 16: 188-91

9. Hall WA, Truwit CL. The surgical management of infections involving the cerebrum. Neurosurgery. 2008. 62: 519-30

10. Kelly DL, Smith JM. Epidural hematoma secondary to frontal sinusitis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1968. 28: 67-9

11. Kim YS, Moon KS, Lee KH, Jung TY, Jang WY, Kim IY. Spontaneous acute epidural hematoma developed due to skull metastasis of hepatocelluar carcinoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016. 11: 741-4

12. Moonis G, Granados A, Simon SL. Epidural hematoma as a complication of sphenoid sinusitis and epidural abscess: A case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. 2002. 26: 382-5

13. Mortazavi MM, Khan MA, Quadri SA, Suriya SS, Fahimdanesh KM, Fard SA. Cranial osteomyelitis: A comprehensive review of modern therapies. World Neurosurg. 2018. 111: 142-53

14. Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, van Dellen JR. Cranial extradural empyema in the era of computed tomography: A review of 82 cases. Neurosurgery. 1999. 44: 748-53

15. Nicoli TK, Oinas M, Niemela M, Makitie AA, Atula T. Intracranial suppurative complications of sinusitis. Scand J Surg. 2016. 105: 254-62

16. Pruthi N, Balasubramaniam A, Chandramouli BA, Somanna S, Devi BI, Vasudevan PS. Mixed-density extradural hematomas on computed tomography-prognostic significance. Surg Neurol. 2009. 71: 202-6

17. Szyfter W, Bartochowska A, Borucki L, Maciejewski A, Kruk-Zagajewska A. Simultaneous treatment of intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018. 275: 1165-73

18. Takahashi Y, Hashimoto N, Hino A. Spontaneous epidural hematoma secondary to sphenoid sinusitis-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010. 50: 399-401

19. Tamaoka S, Shindo J, Tsuchihashi T, Bamba M, Iwata S. A 9-year-old boy with a sinus-related epidural abscess caused by Listeria monocytogenes. Pediatr Int. 2020. 62: 502-3

20. Whitten CA, Moyar JB. Chronic epidural abscess and condensing osteomyelitis of the frontal bone. J Neurosurg. 1955. 12: 516-9