- Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University Hospital, Pathum Thani, Thailand.

Correspondence Address:

Gahn Duangprasert, Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University Hospital, Pathum Thani, Thailand.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_734_2022

Copyright: © 2022 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Gahn Duangprasert, Dawood Kebboonkird, Warot Ratanavinitkul, Dilok Tantongtip. A rare case of ruptured anterior cerebral artery infected aneurysm with angioinvasion secondary to disseminated Nocardia otitidiscaviarum: A case report and literature review. 16-Sep-2022;13:417

How to cite this URL: Gahn Duangprasert, Dawood Kebboonkird, Warot Ratanavinitkul, Dilok Tantongtip. A rare case of ruptured anterior cerebral artery infected aneurysm with angioinvasion secondary to disseminated Nocardia otitidiscaviarum: A case report and literature review. 16-Sep-2022;13:417. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/11874/

Abstract

Background: The cases of ruptured infected aneurysms secondary to disseminated nocardiosis are exceptionally rare. Therefore, there is no guideline for investigation or optimal treatment.

Case Description: A 51-year-old man with immunocompromised status was first presented with pneumonia and cerebral infarction, where the infected aneurysm was ruptured thereafter. Intraoperative findings revealed left anterior cerebral artery thrombosis and occlusion with evidence of angioinvasion along with pus discharge which was later identified with Nocardia otitidiscaviarum. Our case was the first to report on the angioinvasive nature of cerebral nocardiosis, which occurs concurrently with a ruptured infected aneurysm and an unusual presentation that made the diagnosis and treatment challenging.

Conclusion: Cerebral nocardiosis may cause ruptured infected aneurysms in patients with risk factors, especially for immunocompromised hosts. Furthermore, Nocardia can present with severe cerebral manifestation due to angioinvasion causing cerebral infarction accompanied by a ruptured infected aneurysm.

Keywords: Anterior cerebral artery aneurysm, Case report, Cerebral nocardiosis, Infected aneurysm, Nocardia

INTRODUCTION

Infected intracranial aneurysms are rare, describing 2–6% of all intracranial aneurysms[

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient, a 51-year-old man with a history of autoimmune hepatitis, was prescribed prednisolone (30 mg/day) and had been used for 1 month together with tenofovir (300 mg/day) and azathioprine (50 mg/day). The patient was admitted to our institution after subacute fever and dyspnea for 10 days. Physical examination and the investigations showed sepsis due to pneumonia where the pathogen was not yet revealed from the culture study. The patient has been prescribed piperacillin (16 g/day) and tazobactam (2 g/day) for empirical therapy. Other infection sources were ruled out, including unremarkable results of echocardiography. After 2 days of admission, the patient developed drowsiness where physical examination revealed 13 on Glasgow Coma Scaling. Brain computed tomography (CT) showed cerebral infarction in bilateral anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territory, which is more prominent on the right side, and intracerebral hemorrhage in the right frontal region without evidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage [

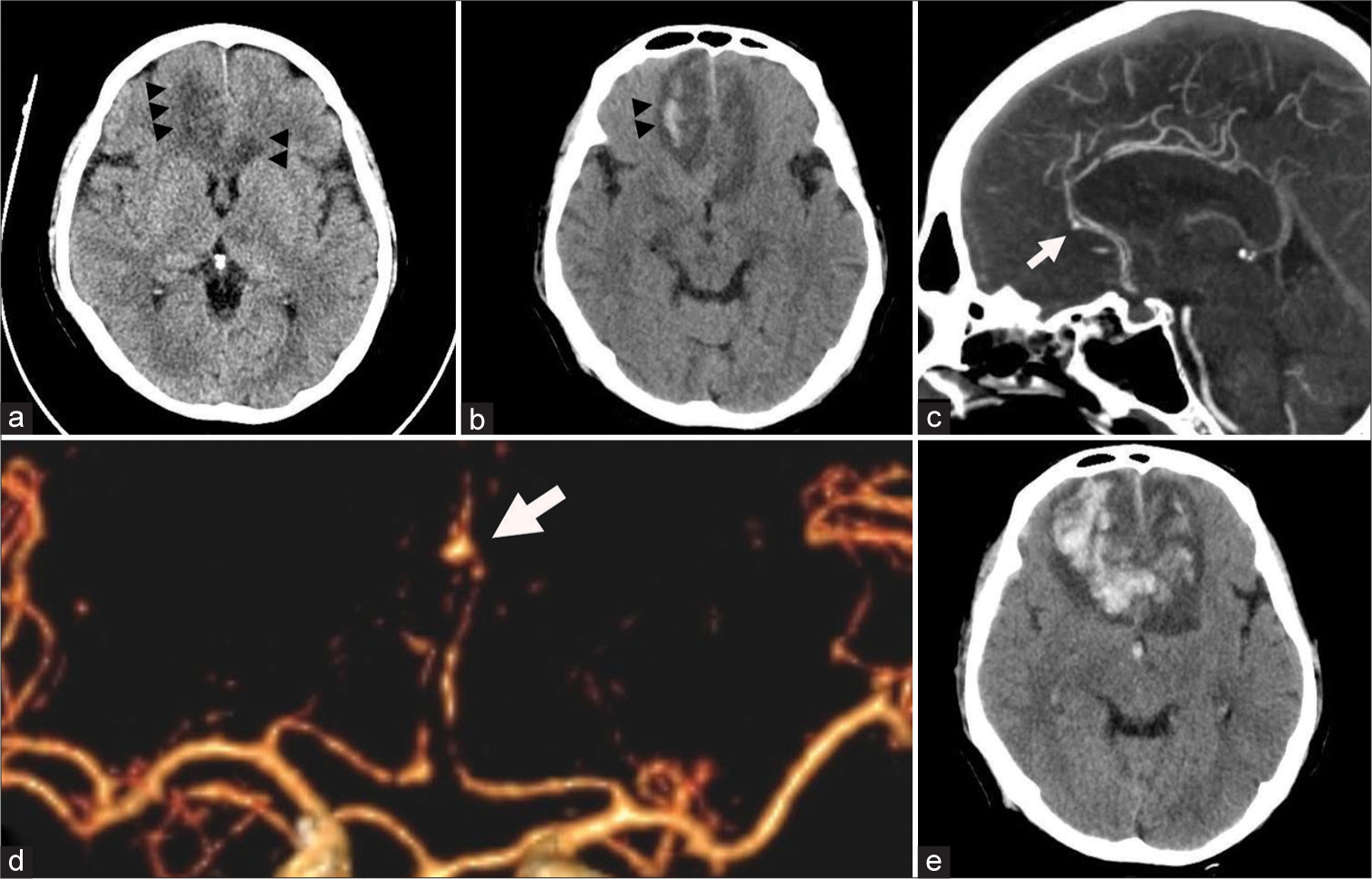

Figure 1:

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain. (a) Cerebral infarction was noted at bilateral anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territory which is more prominent on the right side (arrowheads). (b) Small intracerebral hemorrhage was noted in the right frontal region (arrowheads). CT angiography (CTA) (c) showing distal A2 segment aneurysm (white arrow). (d) Three-dimensional CTA showing left distal A2 segment aneurysm (white arrow). (e) Repeated CT scan of the brain showing expanded hematoma at the bilateral frontal region with intraventricular hemorrhage.

The following day, the patient’s status deteriorated to 5 on Glasgow Coma Scaling. The patient was intubated and underwent another CT brain. CT brain showed expanded hematoma at the right frontal lobe with intraventricular hemorrhage, and left ACA territory infarction was more apparent [

Operation

The procedure was to obliterate the aneurysm with clot evacuation. The patient was set in a supine position, and a bicoronal incision was made. After bifrontal craniotomy, durotomy was performed first on the right side, where brain swelling was prominent, and the clot was partially evacuated. Before interhemispheric dissection, the pus was noticed in the right side subdural space [

Figure 2:

Intraoperative findings. (a) Pus and infected slough were noted along the bilateral frontal cortex, which is prominent on the right side (arrowheads). (b) Pus was identified in the right subdural space consistent with subdural empyema (arrow). After interhemispheric dissection, (c) thrombosis the in left distal ACA was noted at A2 to A3 segment (white arrowheads). (d) The left ACA was whitish in color and covered with slough (black arrowheads) in contrast to the right ACA (asterisk). (e) Flow was not detected in left distal ACA using intraoperative micro-Doppler ultrasound since it was thrombosed. (f) Aneurysm was identified at the left A2 segment (asterisk) with pus along proximal ACA wall (arrow). (g) Clips were applied at both proximal and distal to the aneurysm in an attempt to trap the aneurysm. (h) Pus was also noted in the left subdural space and Sylvian cistern (arrow).

Postoperative course

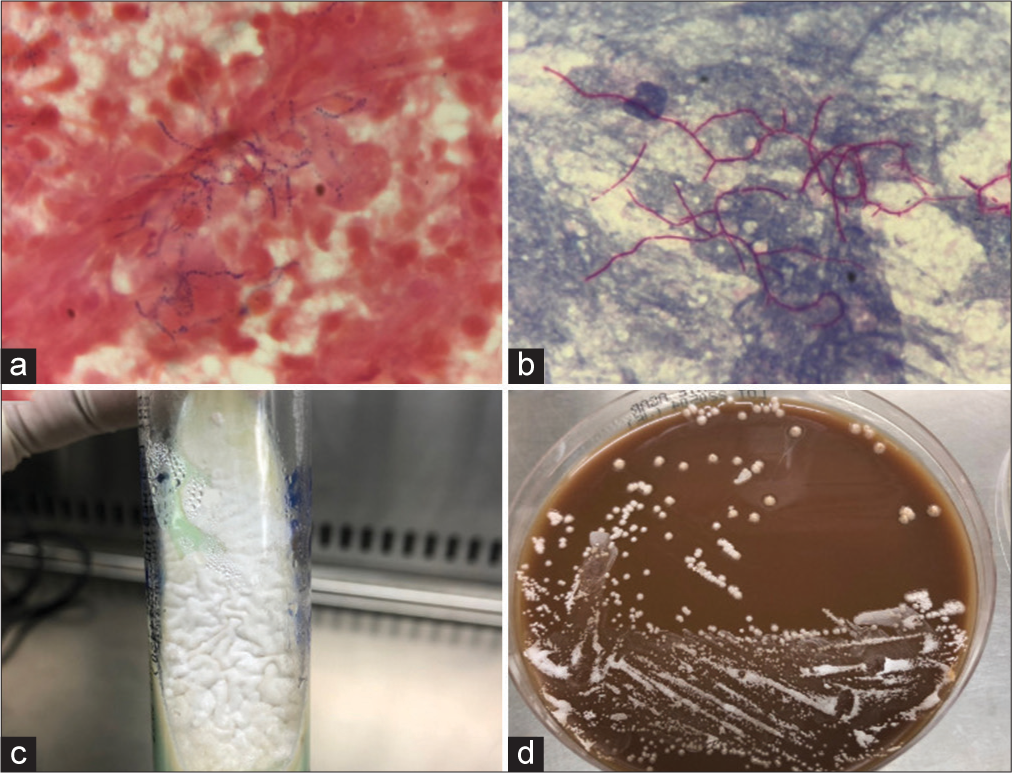

On the day of an operation, the previously sent sputum culture study revealed Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, where the Gram stain showed only mixed organisms. The Gram stain and modified acid-fast stain of subdural pus and thrombus in an aneurysm also showed Gram positive with branching filament, which put suspicion on the Nocardia spp. [

Figure 3:

Microscopic findings from brain pus and thrombus in an. (a) Gram stain showing Gram-positive branching filament with prominent polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the background (×1000). (b) Modified acid-fast staining of the same specimen showing a positive result (×1000). Macroscopic growth of the Nocardia from brain pus and thrombus in an aneurysm. (c) Chalky white colonies were identified in the Lowenstein-Jensen medium. (d) Colonies’ growth was evident in chocolate media after 3 days.

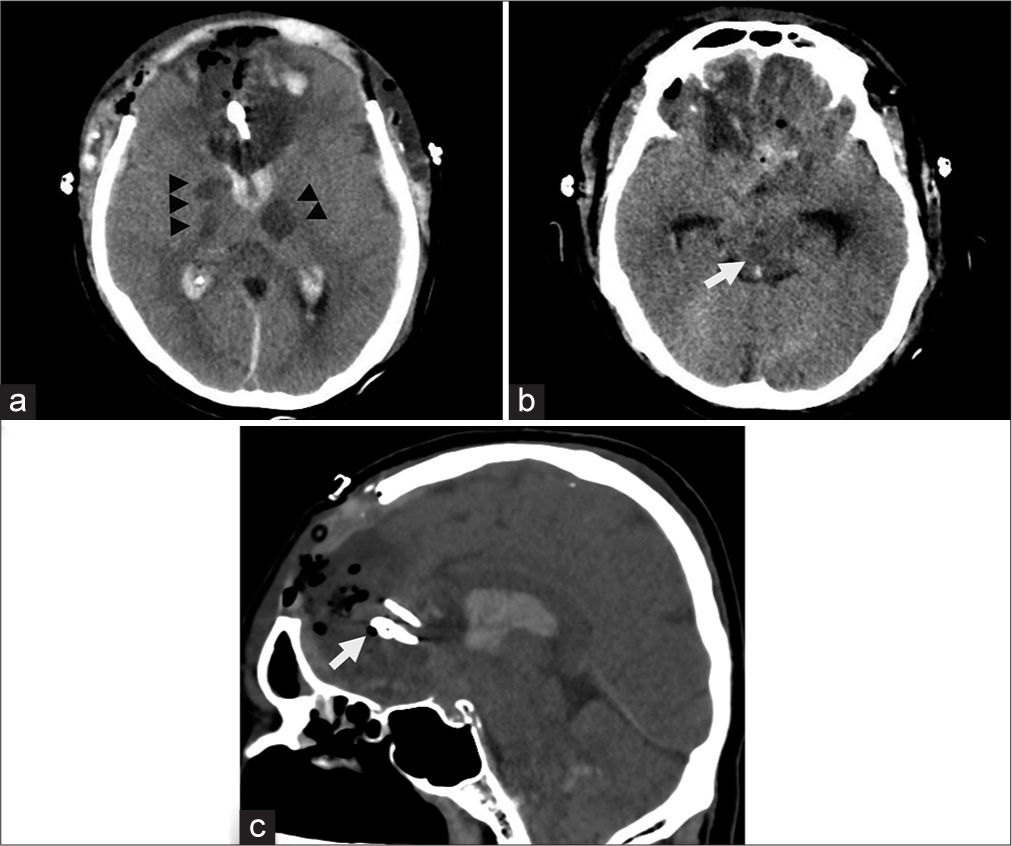

The postoperative CT brain showed multiple infarctions at bilateral subcortical white matter and internal capsule, including the brainstem, which corresponded to an invasion of the bilateral internal carotid artery and basilar artery [

Figure 4:

Postoperative CT scan of the brain. (a) New infarction was evident at the right internal capsule and right thalamus, including the left thalamus (arrowheads). (b) Infarction was also noted at the right midbrain (white arrow). (c) Sagittal view showing the applied clips at proximal and distal to an aneurysm (arrow).

DISCUSSION

Nocardia is soil-borne and aerobic Gram-positive bacteria with branching filaments that can cause opportunistic infection, particularly in immunocompromised hosts. Nocardiosis is most frequently affected in the lungs because inhalation is the primary route of bacterial exposure followed by cerebral infection.[

N. otitidiscaviarum is an infrequent cause of human infections, mainly producing mild cutaneous and lymphocutaneous infections and less virulence than other Nocardia species, which are revealed for only 2% of all Nocardia cases.[

The mycotic aneurysm secondary to fungal infection, the aspergillosis in particular, usually involves the proximal cerebral vasculature with angioinvasive nature where the vessels are destroyed and can be manifested as cerebral infarction.[

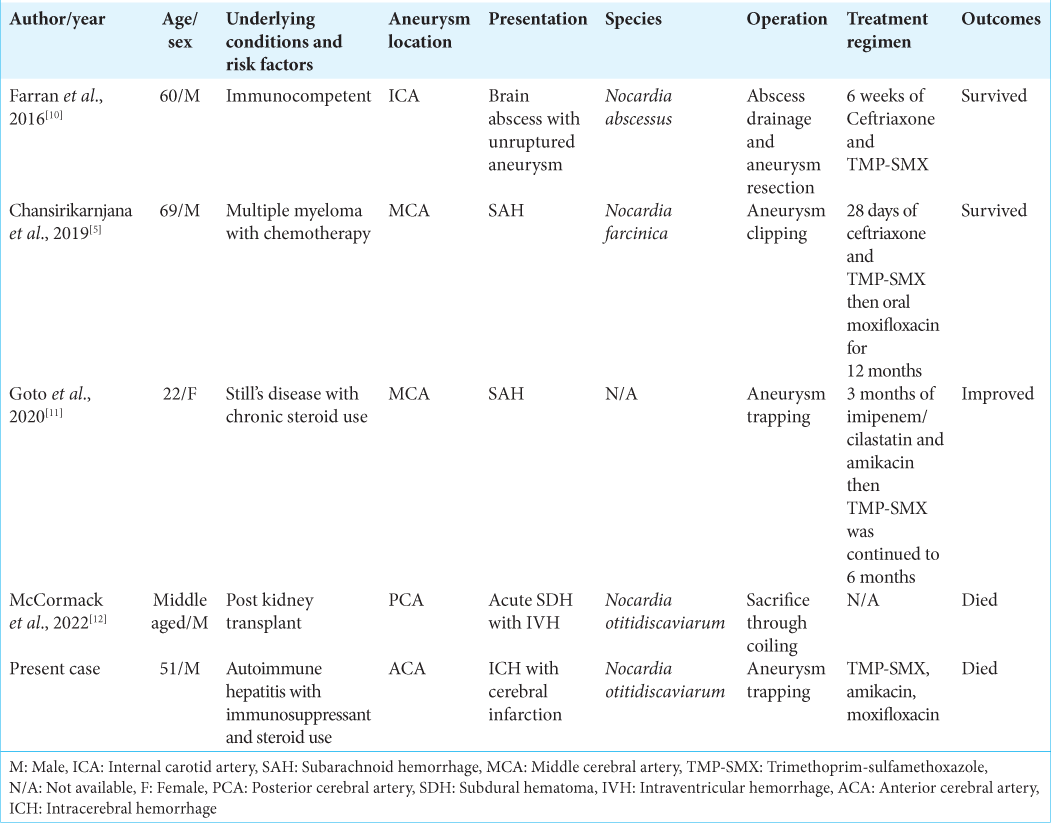

Concerning the outcome of reported cases of Nocardia intracranial infected aneurysms, a good clinical outcome was achieved in two cases where one case had an unruptured aneurysm[

Surgical management for the infected aneurysms has been well described, including clipping, excision, trapping with or without revascularization, and endovascular coiling embolization. The infected aneurysm is usually friable, making simple clipping not feasible.[

CONCLUSION

Cerebral nocardiosis may cause ruptured infected aneurysms in patients with risk factors, especially for immunocompromised hosts. Furthermore, Nocardia can present with severe manifestation due to angioinvasion causing cerebral infarction concurrently with the ruptured infected aneurysm. Therefore, a high index of suspicion with careful evaluation is crucial for prompt diagnosis and adequate treatment despite its rarity.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient’s family for granting us permission to publish this information.

References

1. Allen LM, Fowler AM, Walker C, Derdeyn CP, Nguyen BV, Hasso AN. Retrospective review of cerebral mycotic aneurysms in 26 patients: Focus on treatment in strongly immunocompromised patients with a brief literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013. 34: 823-7

2. Anagnostou T, Arvanitis M, Kourkoumpetis TK, Desalermos A, Carneiro HA, Mylonakis E. Nocardiosis of the central nervous system: Experience from a general hospital and review of 84 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014. 93: 19-32

3. Beaman BL, Beaman L. Nocardia species: Host-parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994. 7: 213-64

4. Bohmfalk GL, Story JL, Wissinger JP, Brown WE. Bacterial intracranial aneurysm. J Neurosurg. 1978. 48: 369-82

5. Chansirikarnjana S, Apisarnthanarak A, Suwantarat N, Damronglerd P, Rutjanawech S, Visuttichaikit S. Nocardia intracranial mycotic aneurysm associated with proteasome inhibitor. IDCases. 2019. 18: e00601

6. Clark NM, Braun DK, Pasternak A, Chenoweth CE. Primary cutaneous Nocardia otitidiscaviarum infection: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995. 20: 1266-70

7. Couble A, Rodríguez-Nava V, De Montclos MP, Boiron P, Laurent F. Direct detection of Nocardia spp. in clinical samples by a rapid molecular method. J Clin Microbiol. 2005. 43: 1921-4

8. Ding J, Ma B, Wei X, Li Y. Detection of Nocardia by 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022. 11: 768613

9. Ducruet AF, Hickman ZL, Zacharia BE, Narula R, Grobelny BT, Gorski J. Intracranial infectious aneurysms: A comprehensive review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010. 33: 37-46

10. Farran Y, Antony S. Nocardia abscessus-related intracranial aneurysm of the internal carotid artery with associated brain abscess: A case report and review of the literature. J Infect Public Health. 2016. 9: 358-61

11. Goto M, Marushima A, Tsuda K, Takigawa T, Tsuruta W, Ishikawa E. Ruptured mycotic cerebral aneurysm secondary to disseminated nocardiosis. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020. 15: 1072-5

12. McCormack E, Cornu O, Hanna J, Nerva JD, Aysenne A. A case of infected intracranial aneurysm with Nocardia meningitis treated with endovascular therapy: Case report and literature review. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2022. 27: 101417

13. Mootsikapun P, Intarapoka B, Liawnoraset W. Nocardiosis in Srinagarind hospital, Thailand: Review of 70 cases from 1996-2001. Int J Infect Dis. 2005. 9: 154-8

14. Saubolle MA, Sussland D. Nocardiosis: Review of clinical and laboratory experience. J Clin Microbiol. 2003. 41: 4497-01

15. Scott A, Meyer JB, Shilpakar SK, Sharma MR, David S, Gordon H, Winn HR.editors. Infectious Aneurysms. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. p. 3404-9

16. Tamakoshi J, Kimura R, Takahashi K, Saito H. Pulmonary reinfection by Nocardia in an immunocompetent patient with bronchiectasis. Intern Med. 2018. 57: 2581-4

17. Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: Updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012. 87: 403-7