- Department of Neurosurgery, Max Superspeciality Hospital, New Delhi, India

- Department of Neurosurgery, Fortis Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

- Department of Psychiatry, Synapse Clinic, Ludhiana, Punjab, India

- Department of Neurosurgery, Max Hospitals, New Delhi, India

- Department of Pathology, Max Superspeciality Hospital, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Hershdeep Singh, Department of Neurosurgery, Fortis Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_476_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Anil Dhar1, Hershdeep Singh2, Sanjeev Dua1, Harneet Kaur3, Amitabh Goel4, Rooma Ambastha5. A sequential occurrence of neurocysticercosis and concomitant benign and malignant brain lesions: A case report of a 43-year-old Indian male. 10-Jan-2025;16:8

How to cite this URL: Anil Dhar1, Hershdeep Singh2, Sanjeev Dua1, Harneet Kaur3, Amitabh Goel4, Rooma Ambastha5. A sequential occurrence of neurocysticercosis and concomitant benign and malignant brain lesions: A case report of a 43-year-old Indian male. 10-Jan-2025;16:8. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/13329/

Abstract

Background: The occurrence of multiple brain tumors of different cellular origins in a single individual is extremely rare. There is limited documentation regarding the incidence of intracranial neoplasms in individuals with preexisting neurocysticercosis (NCC).

Case Description: We report the case of a 43-year-old male who had been under our care since he first suffered from seizures 2½ years ago when he was diagnosed with NCC. A year after the diagnosis of NCC, he presented to the emergency room with seizures, when he was found to have a new small left frontal meningioma, which was managed conservatively. In the next year, the patient was admitted to the emergency room in a disoriented state, and his imaging revealed a new lesion – a left frontal glioma, for which he was operated. Six months later, another glioma was found in the right frontal region, which was excised surgically. Four months after the second surgery, the patient was brought with intractable seizures when he was diagnosed with cerebrospinal fluid spread of NCC. During this admission, the patient expired due to a pulmonary infection.

Conclusion: This case report presents the sequential occurrence of neurocysticercosis, meningioma, and glioma in an Indian male patient. The occurrence of NCC with brain tumors is rarely reported in the literature; further research is needed to understand the occurrence of multiple brain tumors, especially in the setting of preexisting NCC.

Keywords: Glioma, Meningioma, Multiple, Neoplasms, Neurocysticercosis

INTRODUCTION

The occurrence of multiple primary brain tumors in a single individual is infrequent, especially when these tumors originate from distinct cellular types. Such cases are particularly rare and are often associated with prior radiation exposure or phakomatoses.[

CASE REPORT

In September 2022, a 43-year-old male presented with recent onset personality change and forgetfulness over the past 20 days. On examination, the patient was not oriented to time, place, or person; his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 14 (E4V4M6), and his mini-mental state examination score was 22. The patient also displayed features of acalculia as well as decreased power in the right upper and lower limbs (4/5). No sensory deficits were observed.

His medical history included an episode of NCC, treated 2½ years back with albendazole 15 mg/kg over 4 weeks 1 month; no concurrent medical conditions or relevant family history was reported at presentation. Finally, his medication consisted of antiepileptic medication only.

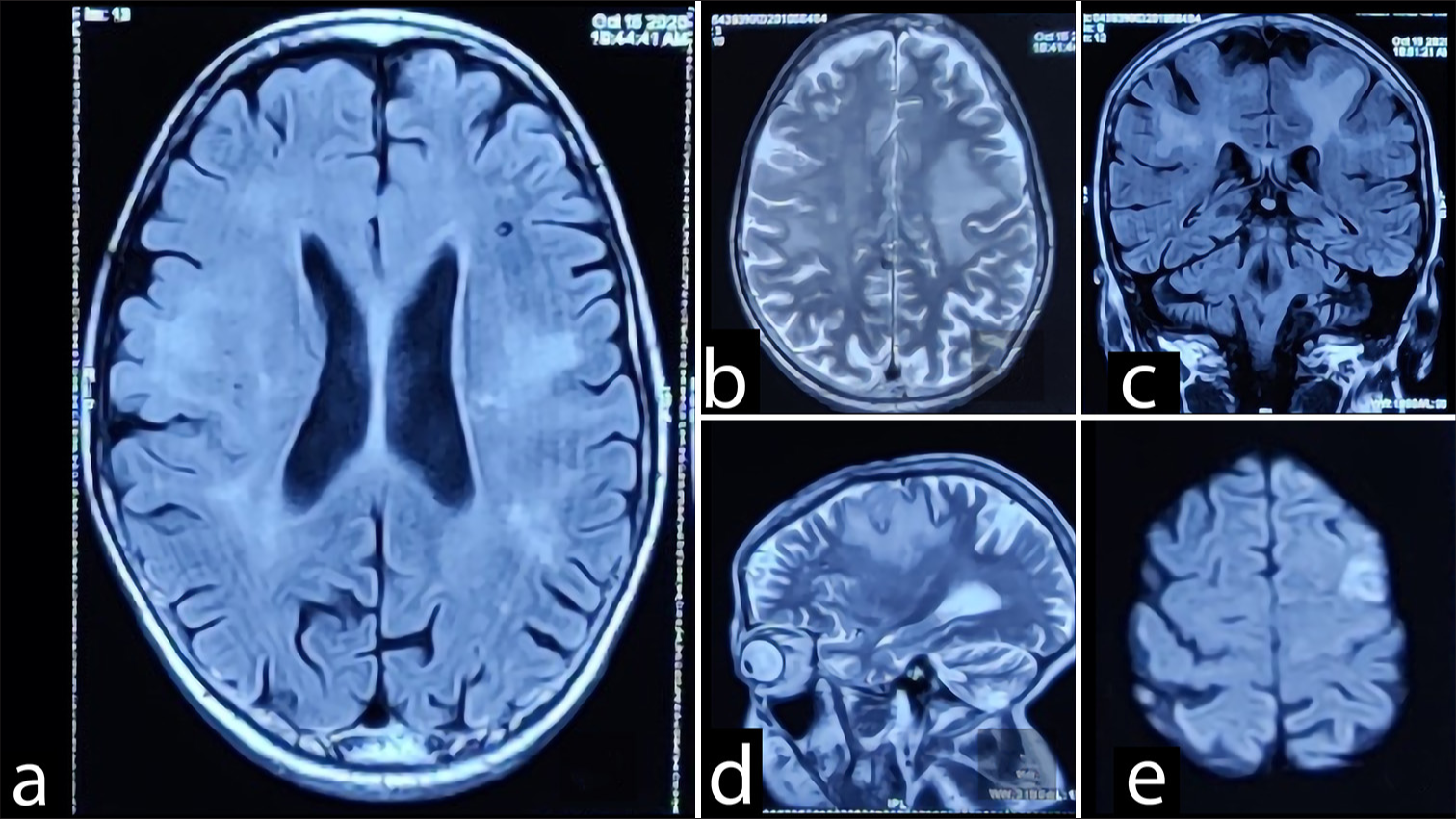

On his regular follow-up imaging the previous year, a new small hyperintense lesion on T2 was observed, suggestive of meningioma (1.5 cm × 2 cm) [

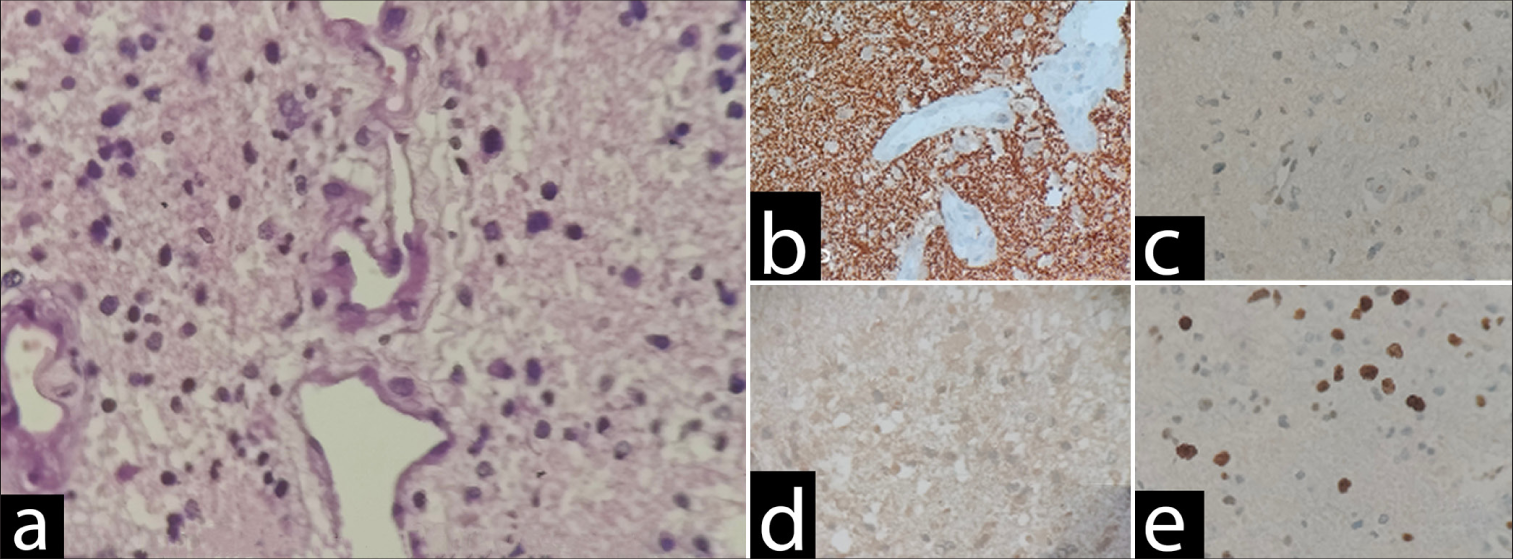

Figure 1:

(a) Multiple foci of GRE blooming seen in left cerebellum, bilateral temporal, bilateral basal ganglia, frontoparietal and occipital region. (b) Lesions are iso to hypointense on T1W/T2W/Flair-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. (c and d) Perifocal edema seen around some of these, largest in right frontoparietal parasagittal region measuring 7 mm in axial plane. (e) Small meningioma was found on left posterior frontal region.

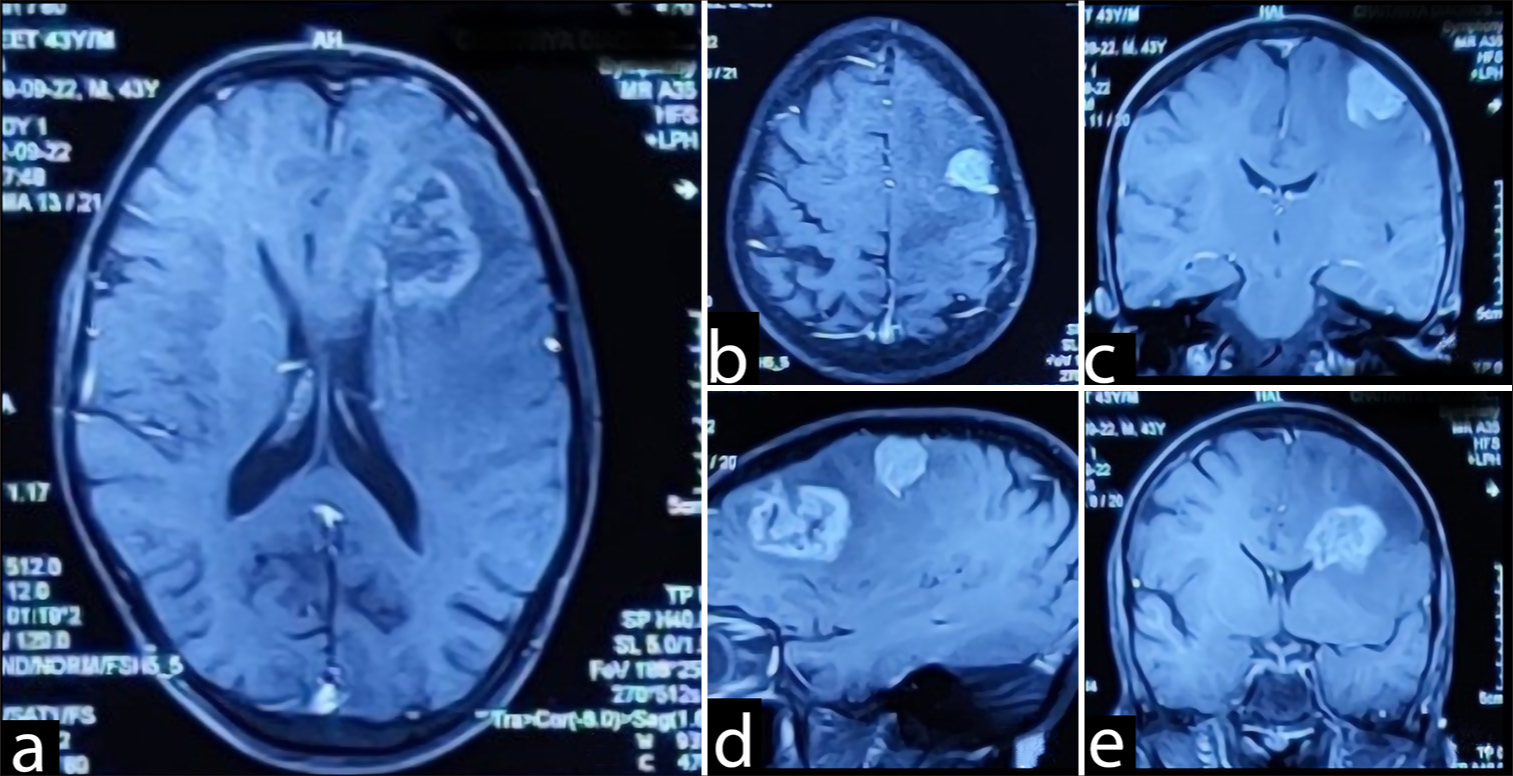

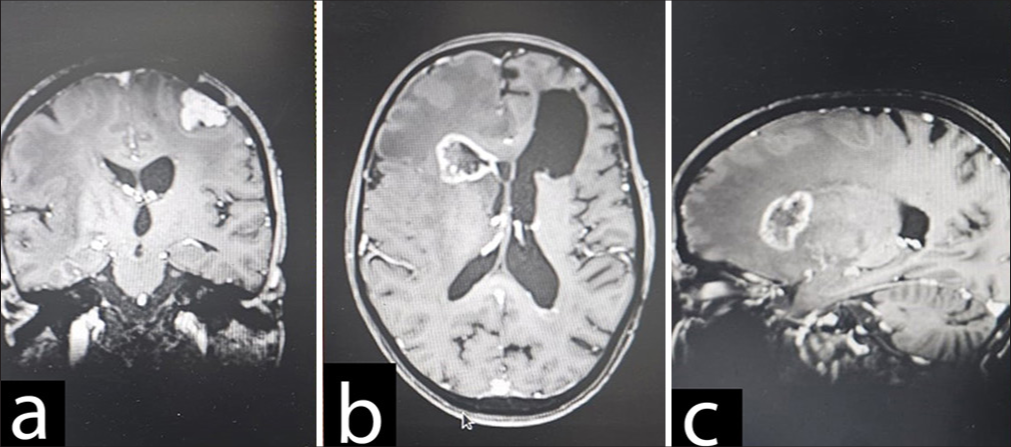

On current admission, the ensuing brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

Figure 2:

(a) T2 hyperintense lesion (4.2 x 3.5 cm) in the left frontal region with extensive edema with heterogeneous contrast enhancement suggestive of Glioma .(b-e) Another extra-axial T2 hyperintense lesion is in the left posterior frontal region measuring (2.0 x 2.4 cm) with contrast enhancement suggestive of meningioma.

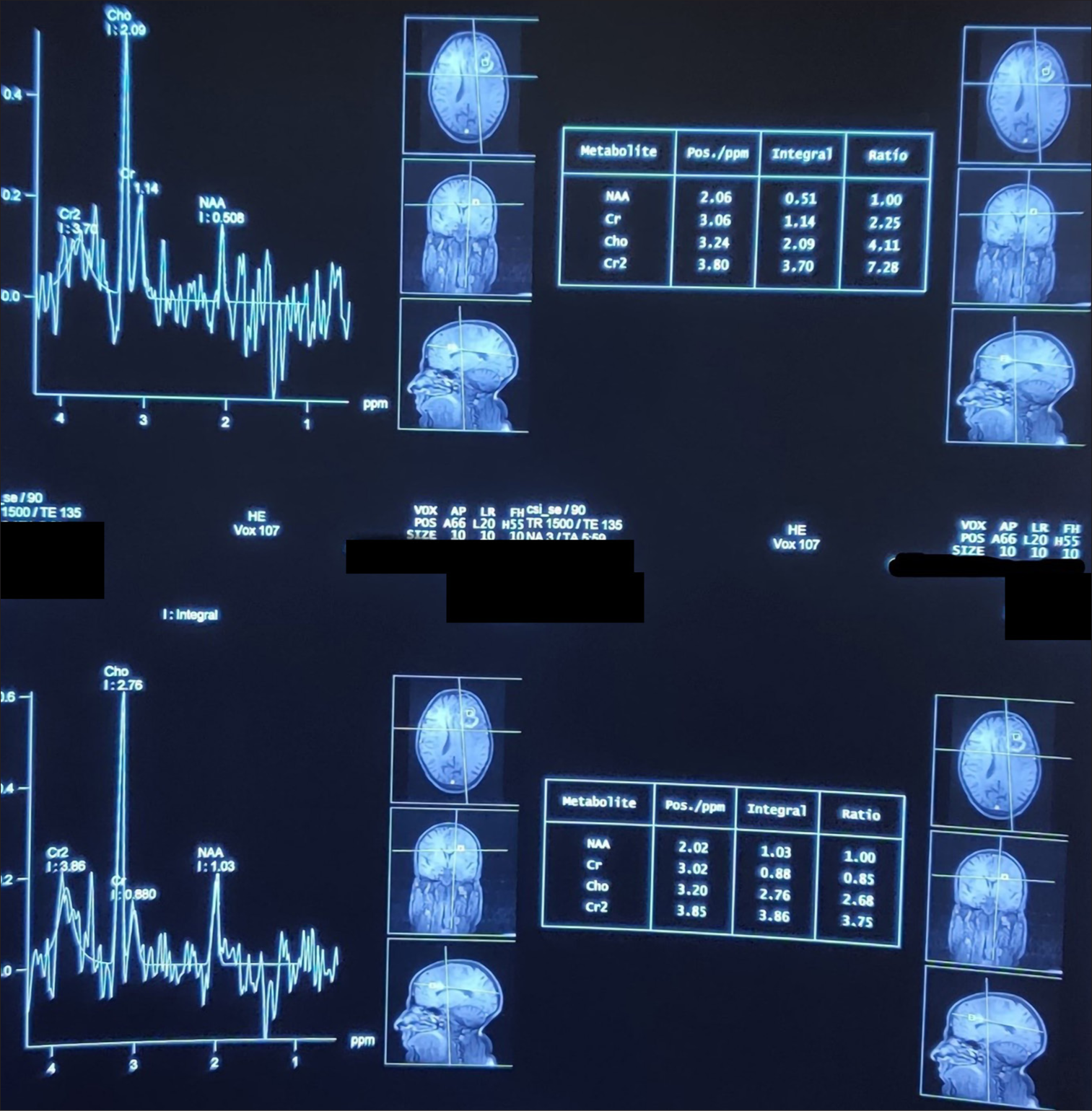

A T2 hyperintense lesion (4.2 × 3.5 cm) in the left frontal region with extensive edema; the lesion showed heterogeneous contrast enhancement on T1 fat-saturated sequences. The complementary magnetic resonance spectroscopy [ In keeping with the previous MRI the year before, an extra-axial T2 hyperintense 2.0 × 2.4 cm lesion in the left posterior frontal region was again demonstrated. The lesion also showed intense homogenous contrast enhancement on postgadolinium sequences, suggestive of meningioma. Multiple T2 hypointense lesions were observed in both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres bilaterally, all blooming on gradient echo sequence. No abnormal contrast enhancement was seen, suggesting the presence of calcified granulomas.

A surgical plan was made to excise both lesions. A left frontoparietal craniotomy in supine was performed, followed by a small corticectomy in the anterior part of the left middle frontal gyrus. The first tumor (Sample A = suspected to be a glioma) was ill-defined, extending up to the frontal horn of the left lateral ventricle, grayish in color, mildly vascular, and aspiratable.

The second tumor (Sample B = presumed to be meningioma), located in the left posterior frontal region, was approached next and was found attached to the dura, compressing the brain parenchyma. It was found to be grayish and moderately vascular, measuring approximately 2 × 2 cm in dimensions and located about 3 cm lateral to the midline. Due to its dense adherence to the motor strip, only a partial resection was possible after surgery. The patient was extubated and shifted to the intensive care unit. The postoperative period was uneventful [

Upon outpatient review a week later, he was doing well with no significant complaints. The subsequent histopathological examination of sample A [

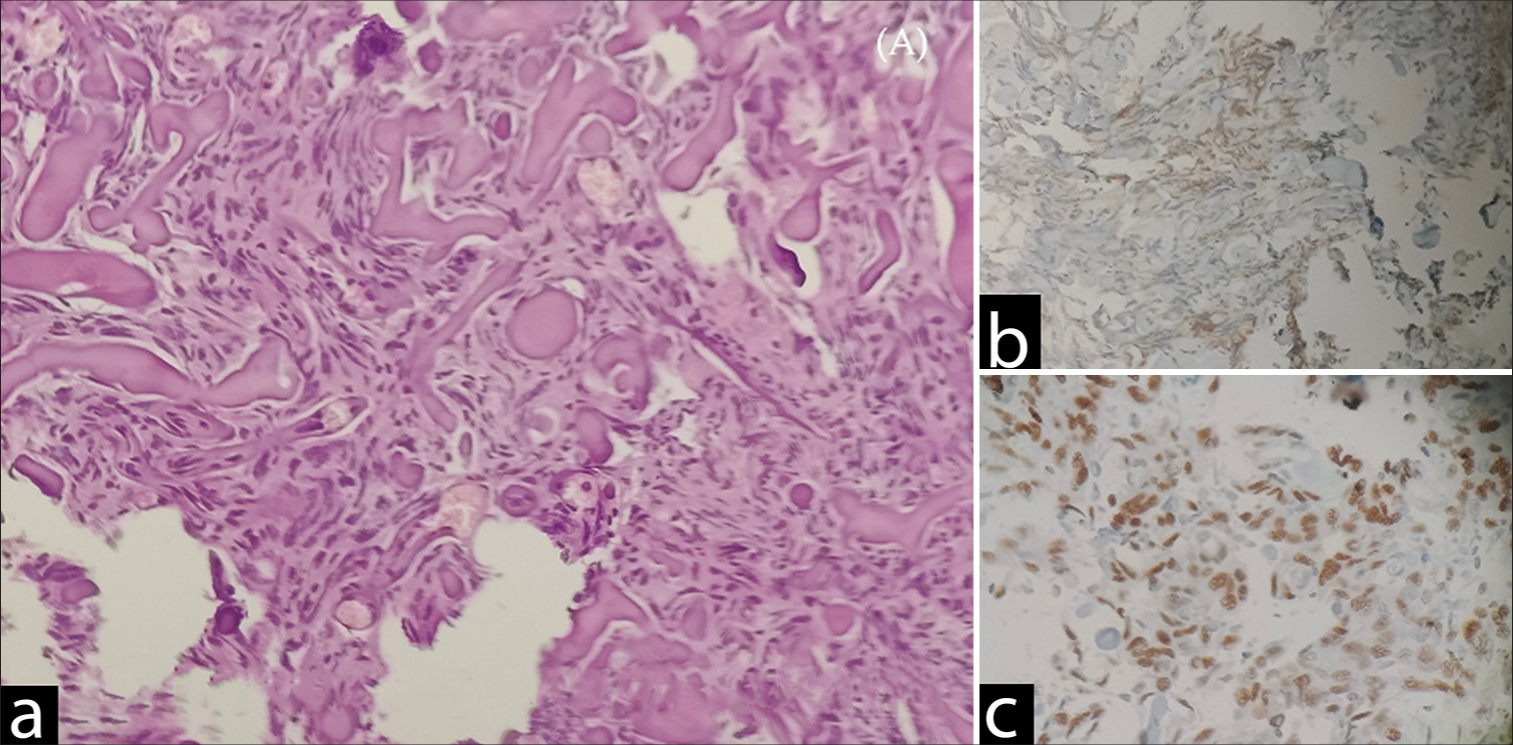

Figure 5:

High-grade diffuse glioma with astrocytic morphology and immunoprofile suggestive of IDH wild-type glioblastoma (central nervous system WHO Grade 4) (a) Sections show a diffuse high-grade glioma with astrocytic morphology. There is microvascular proliferation and increased mitosis. However, necrosis is not identified. (b) GFAP: Diffuse and strongly positive. (c) p53: Patchy (wild type). (d) IDH: Negative. (e) Ki67: 20%. GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein, IDH: Isocitrate dehydrogenase (10x magnification).

Histopathological examination of Sample B [

Figure 6:

Psammomatous meningioma (central nervous system WHO grade 1) (a) Sections show whorls of meningothelial cells with bland nuclei with nuclear pseudoinclusions in few. Numerous psammoma bodies were noted. Negative for increased mitosis, necrosis, direct brain invasion, and features of atypical or anaplastic meningioma. (b) EMA: Diffuse positive. (c) PR: Weak positive. EMA: Epithethelial membrane antigen, PR: Progesterone receptor.

In view of the glioma, the patient underwent standard chemo-radiotherapy (60 Gy in 30 fractions with concurrent temozolomide), followed by temozolomide for the next 6 months.

Long-term follow-up

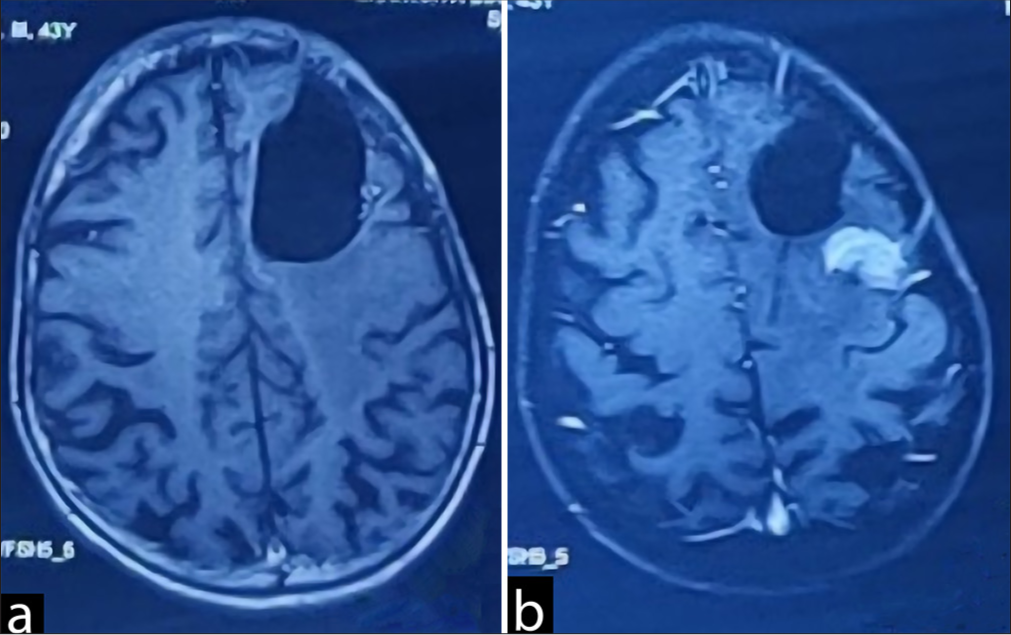

After an uneventful 6 months, the patient was readmitted to the emergency department with complaints of seizures. On the MRI brain [

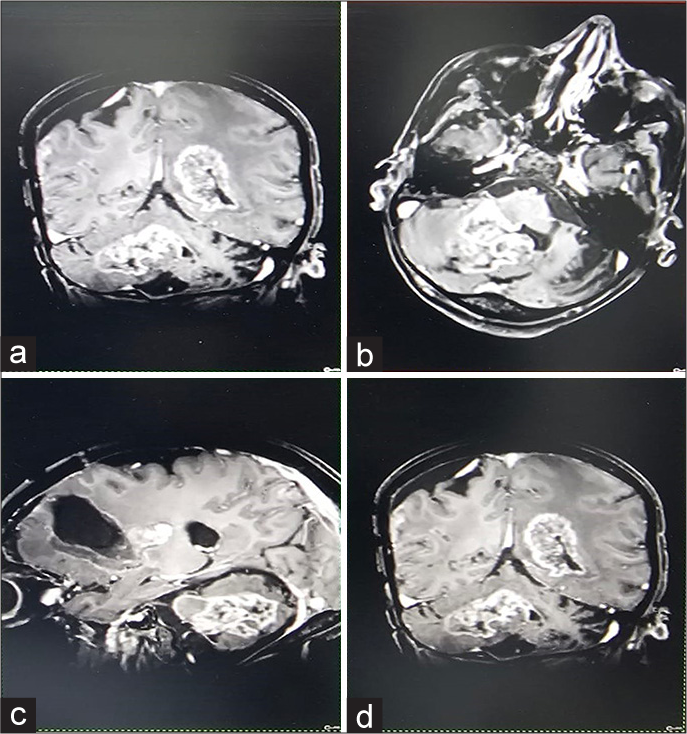

Despite a good recovery in the following 4 months, the patient was readmitted to the emergency department with intractable seizures; on admission, the GCS score was 9 (E4V1M) with restricted left eye movements. The ensuing contrast MRI [

Figure 9:

(a) Multiple lobulated heterogeneously enhancing lesions in bilateral cerebral hemispheres, bilateral occipitoparietal region, left high frontal subcortical region, right cerebellar hemisphereprotruding into 4th ventricle. (b and c) Largest lesion is noted in 4th ventricle measuring 4.7x3.9x3.1 cm. (d) Irregular gyral enhancement with associated gyral thickening noted in bilateral occipitoparietal regions, possibility of Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spread.

DISCUSSION

This case report highlights the diagnostic and management challenges posed by the complex interplay between concomitant brain lesions and infectious entities.

In general, the development of concurring primary brain tumors with different cellular origins remains a rare phenomenon.[

Without clear evidence, mainly two theories have been proposed to explain such unusual findings. The pathogenesis has been ascribed to perilesional tissue irritation, a result of edema associated with the tumor; the irritation is believed to induce arachnoid or astrocyte transformation, subsequently leading to tumorigenesis. In addition, a genetic pathway has been proposed, which includes abnormalities of p53, receptor tyrosine kinases, notch, Wnt (Wingless-related integration site), and other signal transduction mechanisms.[

In the same fashion, Amatya et al. reported that the p53-positivity rate was <5% in all cases of benign meningioma, whereas it was >10% in 19% of cases of atypical meningiomas and 70% of cases of anaplastic meningiomas.[

Studies by Nestler et al. and Ohba et al.,[

Association of brain tumors with NCC

The management approach in this case involved a combination of surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, which aligns with standard protocols for high-grade gliomas and meningiomas. The initial decision to manage the meningioma symptomatically due to its proximity to the motor strip was prudent, given that aggressive resection could have led to significant neurological deficits. However, the need for excising additional lesions along with late NCC-related dissemination highlights the confronting challenges the patient and the multidisciplinary team had to face throughout follow-up.

NCC is known to be the most common helminthic infection affecting humans, with a widely reported inflammatory response.[

CONCLUSION

Considering the inherently dynamic nature of NCC, close surveillance structured on serial imaging and clinic controls remains of the essence. Indeed, timely imaging with MRI or computed tomography scans allows for effective tracking of disease progression, evaluation of treatment efficacy, and early detection of secondary issues, thereby facilitating optimal patient care. Although existing data are sparse, there is a plausible concern that chronic inflammation and other changes associated with NCC could predispose patients to an increased risk of secondary neoplasms. To address this concern, future studies should focus on large-scale epidemiological investigations to determine if NCC is linked to a higher incidence of brain tumors. Aiming to improve relevant treatment strategies, mechanistic research with large cohorts is warranted to uncover the biological pathways through which NCC might influence tumor development, including those involving prolonged inflammation and/or immune system alterations.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Amatya VJ, Takeshima Y, Inai K. Methylation of p14(ARF) gene in meningiomas and its correlation to the p53 expression and mutation. Mod Pathol. 2004. 17: 705-10

2. Abdollahi A, Razavian I, Razavian E, Ghodsian S, Almukhtar M, Marhoommirzabak E. Toxoplasma gondii infection/exposure and the risk of brain tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022. 77: 102119

3. Davis GA, Fabinyi GC, Kalnins RM, Brazenor GA, Rogers MA. Concurrent adjacent meningioma and astrocytoma: A report of three cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1995. 36: 599604

4. Del Brutto OH, Dolezal M, Castillo PR, García HH. Neurocysticercosis and oncogenesis. Arch Med Res. 2000. 31: 1515

5. Kudesia S, Santosh V, Pal I, Das S, Shankar SK. Neurocysticercosis-a clinicopathological appraisal. Med J Armed Forces India. 1998. 54: 13-8

6. Kumar N, Bhattacharya T, Kumar R, Radotra BD, Mukherjee KK, Kapoor R. Is neurocysticercosis a risk factor for glioblastoma multiforme or a mere coincidence: A case report with review of literature. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013. 4: 67-9

7. Maizels RM, Smits HH, McSorley HJ. Modulation of host immunity by Helminths: The expanding repertoire of parasite effector molecules. Immunity. 2018. 49: 801-18

8. Mayer DA, Fried B. The role of Helminth infections in carcinogenesis. Adv Parasitol. 2007. 65: 239-96

9. Nestler U, Schmidinger A, Schulz C, Huegens-Penzel M, Gamerdinger UA, Koehler A. Glioblastoma simultaneously present with meningioma--report of three cases. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007. 68: 145-50

10. Ohba S, Shimizu K, Shibao S, Miwa T, Nakagawa T, Sasaki H. A glioblastoma arising from the attached region where a meningioma had been totally removed. Neuropathology. 2011. 31: 606-11

11. Ramamurthi B, Balasubramaniam V. Experience with cerebral cysticercosis. Neurol India. 1970. 18: 89-91

12. Ramirez MP, Restrepo JE, Syro LV, Rotondo F, Londoño FJ, Penagos LC. Neurocysticercosis, meningioma, and silent corticotroph pituitary adenoma in a 61-year-old woman. Case Rep Pathol. 2012. 2012: 340840

13. Salvati M, D’Elia A, Melone GA, Brogna C, Frati A, Raco A. Radio-induced gliomas: 20-year experience and critical review of the pathology. J Neuro Oncol. 2008. 89: 169-77

14. Schoenberg BS. Multiple primary neoplasms and the nervous system. Cancer. 1977. 40: 19617

15. Spallone A, Santoro A, Palatinsky E, Giunta F. Intracranial meningiomas associated with glial tumours: A review based on 54 selected literature cases from the literature and 3 additional personal cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991. 110: 133-9

16. Suzuki K, Momota H, Tonooka A, Noguchi H, Yamamoto K, Wanibuchi M. Glioblastoma simultaneously present with adjacent meningioma: Case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2010. 99: 147-53

17. Tunthanathip T, Kanjanapradit K, Ratanalert S, Phuenpathom N, Oearsakul T, Kaewborisutsakul A. Multiple, primary brain tumors with diverse origins and different localizations: Case series and review of the literature. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2018. 9: 593-607