- Department of Neurosurgery, Riverside University Health System - Medical Center, Cactus Avenue, Moreno Valley, CA, USA

- Department of Biomedical Science, Graduate College of Biomedical Sciences, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California, USA

Correspondence Address:

Samir Kashyap

Department of Neurosurgery, Riverside University Health System - Medical Center, Cactus Avenue, Moreno Valley, CA, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.206007

Copyright: © 2017 Surgical Neurology International This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Samir Kashyap, Hammad Ghanchi, Tanya Minasian, Fanglong Dong, Dan Miulli. Abdominal pseudocyst as a complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: Review of the literature and a proposed algorithm for treatment using 4 illustrative cases. 10-May-2017;8:78

How to cite this URL: Samir Kashyap, Hammad Ghanchi, Tanya Minasian, Fanglong Dong, Dan Miulli. Abdominal pseudocyst as a complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: Review of the literature and a proposed algorithm for treatment using 4 illustrative cases. 10-May-2017;8:78. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/abdominal-pseudocyst-as-a-complication-of-ventriculoperitoneal-shunt-placement-review-of-the-literature-and-a-proposed-algorithm-for-treatment-using-4-illustrative-cases/

Abstract

Background:Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt placement is one of the most commonly performed procedures in neurosurgery. One rare complication is the formation of an abdominal pseudocyst, which can cause shunt malfunction.

Case Descriptions:We present four unique cases of abdominal pseudocyst formation. Our first patient initially presented with a right upper quadrant pseudocyst. Shunt was externalized and the distal end was revised with placement of catheter on the opposite side. He developed another pseudocyst within 5 months of shunt revision and developed another shunt failure. Our second patient had a history of shunt revisions and a known pseudocyst, presented with small bowel obstruction, and underwent laparotomy for the lysis of adhesions with improvement in his symptoms. After multiple readmissions for the same problem, it was thought that the pseudocyst was causing gastric outlet obstruction and his VP shunt was converted into a ventriculopleural shunt followed by percutaneous drainage of his pseudocyst. Our third patient developed hydrocephalus secondary to cryptococcal meningitis. He developed abdominal pain secondary to an abdominal pseudocyst, which was drained percutaneously with relief of symptoms. The fourth patient had a history of multiple shunt revisions and a previous percutaneous pseudocyst drainage that recurred with cellulitis and abscess secondary to hardware infection.

Conclusion:Abdominal pseudocysts are a rare but important complication of VP shunt placement. Treatment depends on etiology, patient presentation, and clinical manifestations. Techniques for revision include distal repositioning of peritoneal catheter, revision of catheter into pleural space or right atrium, or removal of the shunt completely.

Keywords: CSFoma, pseudocyst, ventriculoperitoneal shunt

INTRODUCTION

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts are a staple procedure in the neurosurgical field. Its indications vary but the principle of shunting cerebrospinal fluid from the ventricles into the peritoneal space was first introduced in 1908.[

Here, we present four unique presentations of abdominal pseudocyst formation as a complication of VP shunt placement and provide an algorithm for the management of this known, but rare, complication.

CASE REVIEW

Case 1

A 32-year-old male presented to our service with complaints of headache, nausea, vomiting, and a “funny feeling” is his left abdomen, which had been progressing for the past 3 weeks. Patient worked as a commercial truck driver and had been experiencing increasing symptoms when driving at higher altitudes, with some resolution of symptoms as he descended. Patient's past medical history was significant for premature birth with a VP shunt placed when he was approximately 2-month-old for unknown reasons. Patient reported that his first shunt revision occurred in 2009 where his shunt was revised to a right frontal VP shunt. Patient later required a revision at an outside hospital in 2015 because the shunt was complicated distally with a pseudocyst. At that time, the distal portion of the catheter was replaced. Pseudocyst cultures did not grow any organic species.

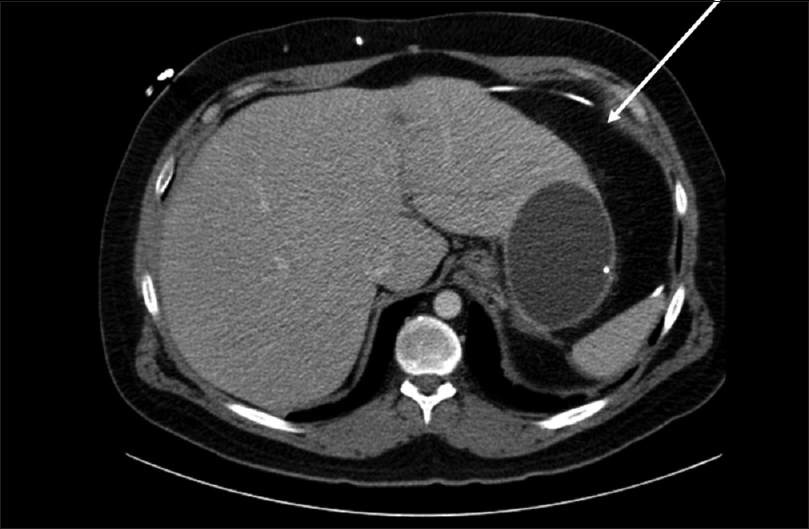

On previous admission to an outside hospital, patient presented with a 3-week history of abdominal pain, gradually worsening. No headaches, nausea, or vomiting were reported at that time. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a 13 cm pseudocyst along the liver margin [

On admission to our hospital 1 year later, patient's CT of the abdomen demonstrated a 10-cm fluid-filled cyst around the distal end of the catheter. On admission, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 2.13. CT of the head demonstrated no evidence of hydrocephalus, however, there were no other images for comparison. A lumbar puncture was performed, which demonstrated an opening pressure greater than 40 cm H2O. CSF studies were negative for infection. Next, the patient's shunt was tapped. Proximal (intracranial) catheter demonstrated significant resistance and was unable to be drained. Distal catheter flushed with ease and demonstrated a pressure of 13 cm H2O, with a manometer held at EAM. CSF studies from this tap demonstrated gram positive rods on gram stain, however, cultures were negative. A decision was made to externalize the shunt (proximal catheter, valve, and distal catheter) and place an external ventricular drain. Patient was placed on vancomycin at the recommendation of infectious disease. Three negative sets of CSF were drawn, each 2 days apart, before returning to the operating room for shunt revision. He was taken to the operating room with the assistance of general surgery for removal of the orphan catheter in his abdomen with the placement of a new catheter.

Case 2

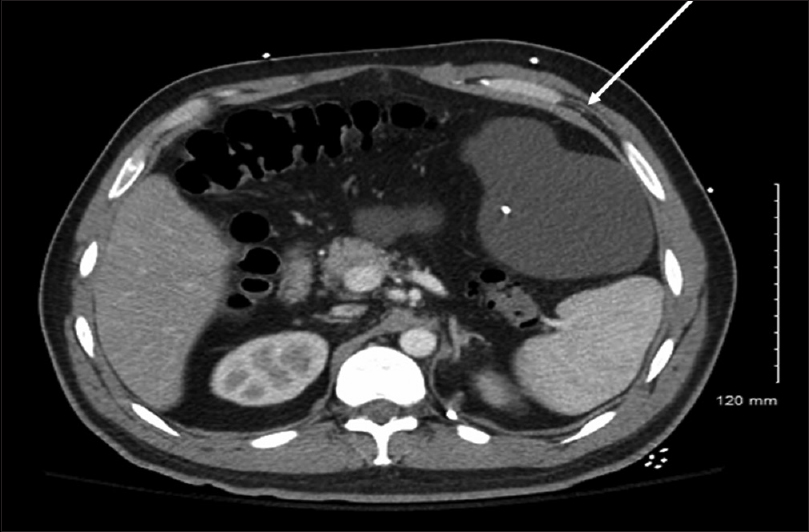

A 32-year-old Caucasian male presented with a history of cerebral palsy and other cognitive deficits at birth with a VP shunt placement as well as during childhood. His cognitive baseline was at the fourth grade level. The patient and his caregiver stated that he has had multiple revisions in the past, which were performed at an outside hospital. In addition, he had a history of recurrent small bowel obstructions, for which he underwent a laparotomy for repair at an outside facility in 2007. He had two subsequent obstructions that resolved with bowel rest. He was initially admitted to our facility in October 2015 with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, and was diagnosed with another small bowel obstruction. ESR on admission was 108; CRP was 14.30. CT of the abdomen at the time showed a pseudocyst in the abdomen measuring 15 × 14 × 10 cm [

It was decided to convert his VP shunt into a ventriculopleural shunt. He underwent removal of the distal portion of the catheter where the peritoneal portion was removed and a new distal catheter was placed in the pleural cavity. He tolerated this procedure well without complication. It was then recommended that the patient have the abdominal pseudocyst aspirated by interventional radiology. Subsequent studies grew no organisms.

Case 3

A 40-year-old male with a history human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and hydrocephalus secondary to cryptococcal meningitis presented to the emergency room with diffuse abdominal pain and three episodes of nausea and vomiting. White blood cell count was elevated at 15.9 on admission, however, ESR and CRP were not obtained. CT head was performed on admission, which showed a narrowing of the lateral ventricles in comparison to previous CT. Neurosurgery and Infectious Disease were consulted for evaluation and a lumbar puncture was recommended. CSF was sent for gram stain and culture, which were negative. A CT of the abdomen was obtained which showed a large pseudocyst measuring 8.4 × 4 cm [

Case 4

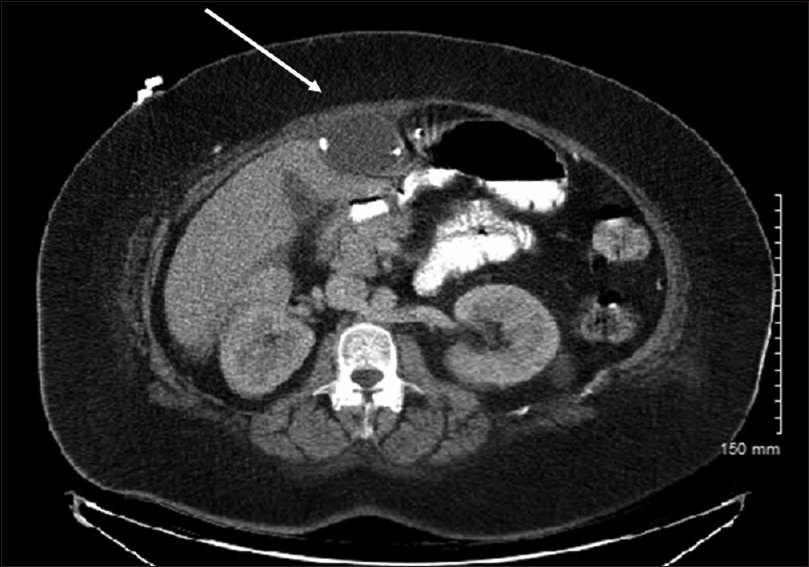

A 43-year-old female presented with a history of VP shunt placed at birth. She had multiple revisions throughout her lifetime. She presented to our service with abdominal pain, severe headaches, mild nausea, but no vomiting, and was found to have worsening hydrocephalus secondary to abdominal pseudocyst [

Six years later, she was admitted to the hospital with sepsis, which was likely secondary to cellulitis as well as poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (A1C = 13.4%). She complained of pain on her abdominal wall, but otherwise had no neurological signs or symptoms. It was noted on admission that she had cellulitis along the tract of her distal shunt catheter. She was also noted to have pockets of underlying abscess in the soft tissue of her abdominal wall on a contrast CT abdomen. ESR on admission was 113; CRP was 22.05. Given the cellulitis secondary to the distal catheter, she underwent bedside externalization of the distal portion of her VP shunt. The culture from the wound, CSF, and catheter tip culture grew Beta Streptococcus Group A, necessitating an Infectious Disease consultation. An endoscopic third ventriculostomy was attempted, however, it could not be safely performed due to diffuse thickening of the floor of her third ventricle. After resolution of the soft tissue infection of her abdominal wall and infectious disease clearance, a new VP shunt was placed on the opposite side. A revision surgery was performed on the left side with the assistance of the general surgery service in laparoscopic placement of the distal catheter.

DISCUSSION

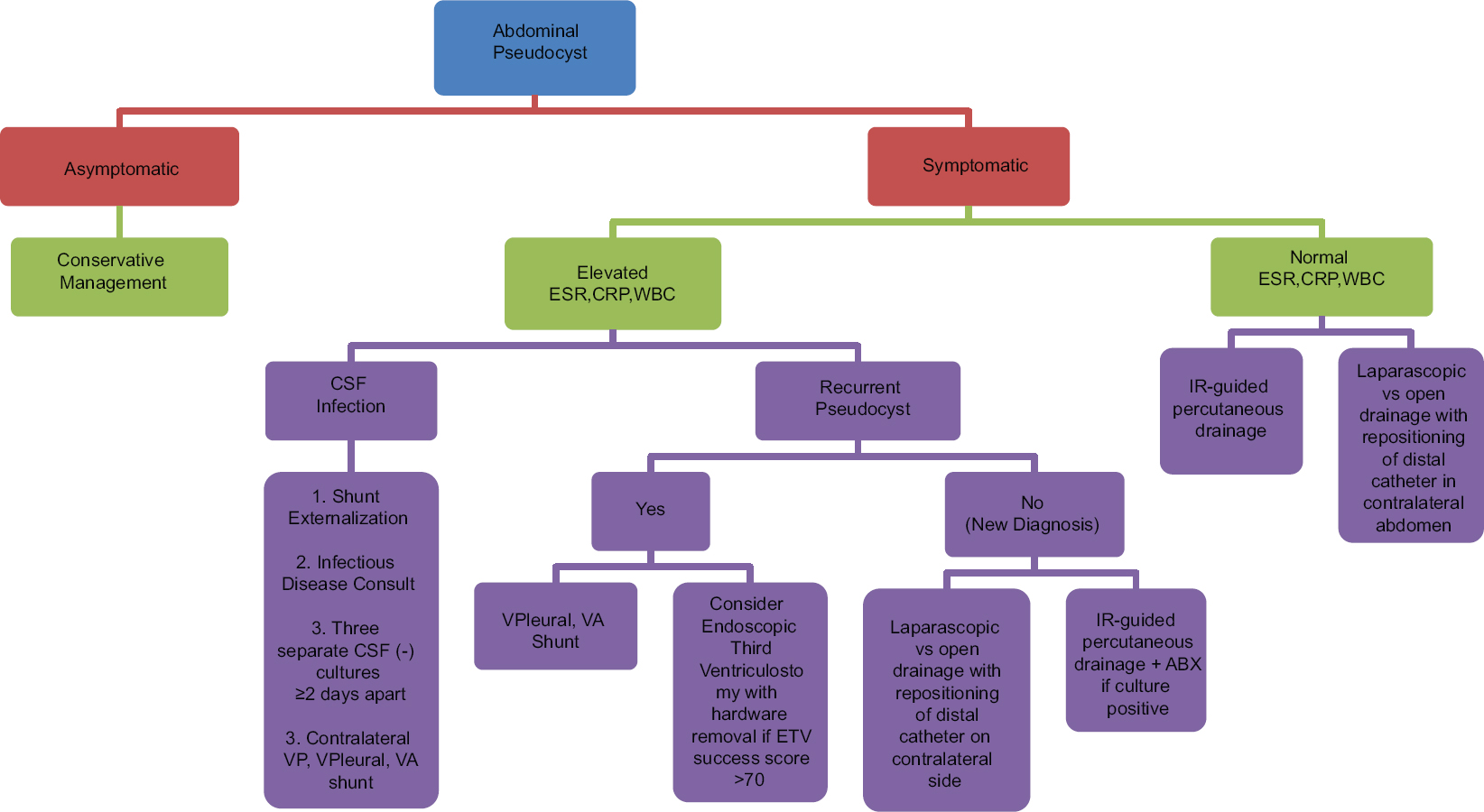

We have presented four cases of APC formation following VP shunt placement. These cases have informed our experience in the diversity of techniques that can be used to manage this complication. We propose an algorithm to select the best treatment option based upon the patient's presentation [

The unique nature of our first case lies in the fact that the patient had an initial shunt revision performed at an outside hospital due to his abdominal pseudocyst causing impaired CSF drainage. The recurrence of APC is not necessarily uncommon, with the incidence in the literature varying widely from 7.1% to 62.5%.[

Our second case is especially rare because, to our knowledge, there have not been any cases of gastric outlet obstruction caused by APC reported in the literature. He was managed conservatively as he was asymptomatic in regards to neurological symptoms. If his pseudocyst was not causing gastric outlet obstruction, no intervention would have been recommended. Percutaneous drainage of the cyst to relieve the obstruction was the initial approach considered, however, given his pro-inflammatory state (ESR: 108, CRP: 14.30), there was a high index of suspicion that it would recur. In addition, it has been reported that there is a higher incidence in patients with prior abdominal surgery or history of necrotizing enterocolitis.[

The third case demonstrates an example of APC as a low-grade inflammatory process and gives credence to the theory that these are secondary to a low-grade infection. It also demonstrates that a first time diagnosis of pseudocyst may be managed with simple percutaneous drainage and appropriate antibiotic treatment, if the CSF remains unaffected. It is important to note that, in addition to gram stain and culture of the APC aspirate, CSF studies should be obtained so that a VP shunt infection can be effectively ruled out.

Our final case reinforces the fact that VP shunts are prone to complications – with infection rates within the first month ranging 3–20%.[

The classic signs of VP shunt malfunction are the same as the typical clinical manifestations of increased intracranial pressure, i.e., headache, nausea, vomiting, and altered level of consciousness. Abdominal complications related to VP shunt placement include pseudocysts (both infected and sterile), abscess, and bowel perforation. With regard to abdominal pseudocysts, the presentation can be more variable. Abdominal pain is often the chief complaint in most patients, accompanied by nausea and vomiting, which is often in the absence of neurological signs. CT scan is often more useful in distinguishing those presenting with severe abdominal pain because it can help identify other etiologies such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, abdominal abscess, or bowel obstruction. The diagnosis of pseudocysts is most accurately made by a contrast CT scan of the abdomen, although ultrasound has been recommended by some due to its frugality. Eliminating radiation exposure is an especially important consideration in the pediatric and pregnant population. The authors recommend CT scan of the abdomen with intravenous contrast as the preferred initial method of diagnosing abdominal pseudocysts, except in cases of pediatrics or pregnancy.

APC have been reported in the literature with the incidence ranging from 0.25% to 10%.[

Treatment of pseudocysts is highly variable and there is no established standard, therefore, the method of treatment should be tailored to the overall clinical picture. Treatment options include percutaneous drainage of the pseudocyst with distal repositioning of peritoneal catheter (open or laparoscopic), placement of distal catheter in an alternative location such as the contralateral abdomen, the pleural space or the right atrium, and endoscopic third ventriculostomy with removal of shunt hardware completely.[

CONCLUSION

Abdominal pseudocysts are a known, but rare, complication of VP shunt placement. It is likely secondary to a low-grade inflammatory process. Diagnosis is best made by contrast CT scan of the abdomen except in childhood and pregnancy. CSF studies via shunt tap or lumbar puncture are also recommended to rule out hardware infection. In regards to the treatment algorithm, we propose placing an emphasis on the selection of alternative locations for shunt placement in symptomatic patients who are found to be in an inflammatory state, along with conservative management in asymptomatic patients. In our experience, this approach has resulted in a simplified approach to treatment in otherwise complicated patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Alduraibi S. Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt with Communicating Peritoneal & Subcutaneous Pseudocysts Formation. Int J Health Sci. 2014. p. 8-

2. Birbilis T, Kontogianidis K, Matis G, Theodoropoulou E, Efremidou E, Argyropoulou P. Intraperitoneal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst. A rare complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Chirurgia. 2008. 103: 351-3

3. Browd SR, Gottfried ON, Ragel BT, Kestle JR. Failure of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: Part II: Overdrainage, loculation, and abdominal complications. Pediatr Neurol. 2006. 34: 171-6

4. Bryant M, Bremer A, Tepas J, Mollitt D, Nquyen T, Talbert J. Abdominal complications of ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Case reports and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1988. 54: 50-5

5. Burchianti M, Cantini R. Peritoneal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts: A complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunts. Child's Nerv Sys. 1988. 4: 286-90

6. Chung JJ, Yu JS, Kim JH, Nam SJ, Kim MJ. Intraabdominal complications secondary to ventriculoperitoneal shunts: CT findings and review of the literature. Am J Roentgenol. 2009. 193: 1311-7

7. Dabdoub CB, Dabdoub CF, Chavez M, Villarroel J, Ferrufino JL, Coimbra A. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst: A comparative analysis between children and adults. Child's Nerv Sys. 2014. 30: 579-89

8. Dabdoub CB, Fontoura EA, Santos EA, Romero PC, Diniz CA. Hepatic cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst: A rare complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Surg Neurol Int. 2013. 4:

9. de Oliveira RS, Barbosa A, Machado HR. An alternative approach for management of abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts in children. Child's Nerv Sys. 2007. 23: 85-90

10. Doran S, Hellbusch L. Abdominal pseudocyst: Predisposing factors and treatment algorithm. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005. 41: 77-83

11. Kausch W. Die behandlung des hydrocephalus der kleinen Kinder. Arch Klin Chir. 1908. 87: 709-96

12. Laurent P, Hennecker J, Schillaci A, Scordidis V. [Abdominal CSF pseudocyst recurrence in a 14-year-old patient with ventricular-peritoneal shunt]. Arch Pediatr. 2014. 21: 869-72

13. Moussa WMM, Mohamed MAA. Efficacy of postoperative antibiotic injection in and around ventriculoperitoneal shunt in reduction of shunt infection: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016. 143: 144-9

14. Pernas JC, Catala J. Case 72: Pseudocyst around Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt 1. Radiology. 2004. 232: 239-43

15. Rainov N, Schobess A, Heidecke V, Burkert W. Abdominal CSF pseudocysts in patients with ventriculo-peritoneal shunts. Report of fourteen cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 1994. 127: 73-8

16. Sharma AK, Pandey AK, Diyora D, Mamidanna R, Sayal P, Ingale HA. Abdominal CSF pseudocyst in a pateint with ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Indian J Sur. 2004. 66:

17. Tamura A, Shida D, Tsutsumi K. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocyst occurring 21 years after ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement: A case report. BMC Surg. 2013. 13: 1-

18. Yuh SJ, Vassilyadi M. Management of abdominal pseudocyst in shunt-dependent hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol Int. 2012. 3: 146-