- Departament of Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Médicas, Fluminense Federal University Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.,

- Departament of Programa de Pós-graduação em Neurologia, Faculdade de Medicina, Fluminense Federal University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Departament of Faculdade de Nutrição, Fluminense Federal University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Departament of de Radiologia Faculdade de Medicina, Fluminense Federal University, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, United States,

- Institute of de Biologia, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Correspondence Address:

Clovis O. da Fonseca

Departament of Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Médicas, Fluminense Federal University Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.,

DOI:10.25259/SNI_445_2020

Copyright: © 2020 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Juliana Guimaraes Santos1, Gisele Faria2, Wanise Da Cruz Souza Da Cruz3, Cristina Asvolinsque Fontes4, Axel H. Schönthal5, Thereza Quirico-Santos6, Clovis O. da Fonseca1. Adjuvant effect of low-carbohydrate diet on outcomes of patients with recurrent glioblastoma under intranasal perillyl alcohol therapy. 11-Nov-2020;11:389

How to cite this URL: Juliana Guimaraes Santos1, Gisele Faria2, Wanise Da Cruz Souza Da Cruz3, Cristina Asvolinsque Fontes4, Axel H. Schönthal5, Thereza Quirico-Santos6, Clovis O. da Fonseca1. Adjuvant effect of low-carbohydrate diet on outcomes of patients with recurrent glioblastoma under intranasal perillyl alcohol therapy. 11-Nov-2020;11:389. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint-articles/10384/

Abstract

Background: Standard of care for glioblastoma (GB), consisting of cytotoxic chemotherapy, steroids, and high-dose radiation, induces changes in the tumor microenvironment through its effects on glucose availability, which is a determinant for tumor progression (TP). Low-carbohydrate diet (LCD) reduces the glucose levels needed to drive the Warburg effect.

Methods: To investigate LCD’s effect on GB therapy, we have begun a clinical trial using LCD as an addition to intranasal perillyl alcohol (POH) for recurrent GB (rGB) patients. This study involved 29 individuals and evaluated, over a period of 1 year, the adjuvant effect of LCD associated with POH therapy in terms of toxicity, extent of peritumoral edema, reduced corticosteroid use, seizure frequency, and overall survival. POH group (n = 14) received solely intranasal POH without specific diet regimen, whereas POH/LCD group (n = 15) received intranasal POH in combination with nutritional intervention. Patients’ assessment was based on clinical reviews and magnetic resonance data.

Results: In the 1-year follow-up, the POH/LCD group showed a 4.4-fold decrease in the proportion of patients who needed treatment with corticosteroids, as well as a reduction in tumor size and peritumoral edema, as compared to the POH group. While 75% of patients undergoing POH treatment experienced seizures, this fraction was reduced to 56% in the POH/LCD group. A 2.07-fold increase in the proportion of patients with stable disease, along with a 2.8-fold decrease in the proportion of patients with TP, was seen in the POH/LCD group.

Conclusion: The results presented in this study show that the LCD associated with intranasal POH therapy may represent a viable option as adjunctive therapy for rGB to improve survival without compromising patients’ quality of life. Prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm these findings and validate the efficacy of this novel therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: Intranasal administration, Low carbohydrate diet, Perillyl alcohol, Recurrent glioblastoma

INTRODUCTION

Glioblastoma (GB) remains the most common and highly heterogeneous primary brain tumor in adults. Current treatment consists of maximal safe resection when possible, followed by combination of radiotherapy and adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy (TMZ).[

One of the impediments to the efficacy of conventional treatment for gliomas has been the degree of invasiveness of tumor cells into the surrounding tissue and peritumoral microenvironment.[

In the above context, reprogramming the energy metabolism of the tumor cells and the tumor inflammatory microenvironment[

Research on risk factors of cancer has shown the impact of glucose metabolism in the development and growth of GB.[

Published studies have conceptualized that ketogenic metabolic therapy exerts simultaneous action on the energy metabolism of tumor cells, on neoangiogenesis, and on neuroinflammation, thus representing a promising strategy for the treatment of GB and other types of brain tumors.[

The rationale underlying our efforts to combine KD with POH treatment centers on specific features that are known to originate from cellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. ER stress represents a cellular mechanism that is based on antagonistic modules, where low stress levels trigger its protective module aimed at re-establishing homeostasis, but where excessive stress turns on its pro-apoptotic module, leading to cell death to protect the organism as a whole. Tumor cells generally are experiencing elevated basal levels of chronic ER stress (due to oxidative stress, acidification, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, etc.) and therefore are more susceptible to killing by treatment conditions that aggravate ER stress even further[

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the adjuvant effect of the low-carbohydrate diet (LCD) on outcomes of patients with rGB under continuous therapy with intranasal POH. The assessment was based on the following parameters: toxicity, extent of peritumoral edema, reduced corticosteroid use, seizure frequency, and overall survival (OS).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection and treatment

Prior study approval was provided by the Ethics Committee of the Medical School of the Fluminense Federal University (UFF-CAAE: 14613313.8.0000.5243), according to local legal requirements and with principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The prospective study was carried out at the Antonio Pedro University Hospital by convenience sampling.

Inclusion criteria at enrollment required adult subjects aged >18 years with rGB on palliative care and under symptomatic treatment after failing to respond to the previous standard treatments, including surgery, and/or radiation, and multimodal chemotherapy specific for GB. Patients had measurable contrast-enhancing tumor on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and Karnofsky performance scale of ≥70. Each patient and a next-of-kin signed a written informed consent before enrollment in the clinical trial of intranasal POH delivery. Patients were followed up for 1 year. To form the two treatment groups, the patients were self-selected: those who wished to adhere to a LCD formed the LCD/POH group, and those who preferred not to adhere to a restricted carbohydrate diet formed the POH group.

Formulation of POH for nasal inhalation delivery was supplied by the Multidisciplinary Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Rio de Janeiro Federal University (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). POH was inhaled 4 times daily (55 mg, 0.3% v/v) totaling 220 mg/day.

Diet details

The anthropometric and biochemical status of each patient was assessed periodically during the study as part of the clinical laboratory routine assessment. Patients of the LCD/POH group received LCD for 1 year. LCD was prescribed according to the following distribution: energy (25–30 kcal/kg); protein 1.5 g/kg of body weight; and 30–35% of total calories from carbohydrate (up to 130 g/day),[

To verify nutritional ketosis, participants received urinalysis strips with instructions for use, and they performed measurements 3 times a week with results being reported weekly to researchers. The level of ketone bodies (5–15 mg/dL) in the urine confirmed patients’ adherence to LCD and a slight increase of urinary ketone bodies. Although the hallmark of nutritional ketosis is the level of ketosis in the blood, a non-invasive method (urinary ketone test strips) was chosen. This was out of necessity because measuring urinary ketones at home was the only possible way for most patients to participate in this part of the study.

Assessment of outcome: tumor size, peritumoral edema, and OS

MR images and updated clinical records were reviewed for all patients. Image examinations were performed at a range of institutions using a 1.5 Tesla MR scanner with a brain coil device. All examinations were included in the complete routine for MR evaluation with multiplane T1W acquisitions prior and subsequent to the venous administration of paramagnetic contrast with volumetric series in 3D, T2, T2/ fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion, and susceptibility-weighted imaging. MR proton spectroscopy and MR perfusion were also performed, and MR images were analyzed by two radiologists with expertise in neuroradiology. A consensus diagnosis was established using a workstation with a picture archiving and communication system at the time of diagnosis and for follow-up data. The image analysis focused on the following characteristics: lesion distribution and volume, signal intensity and T2/ FLAIR image characteristics, peritumoral edema, diffusion restriction patterns, and contrast enhancement. Evaluation of tumor response was based on RANO (Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology) criteria for high-grade gliomas.

Statistical analysis

Kaplan-Meier and log-rank test were selected to evaluate patients’ evolution, where events for consideration included disease progression and death. SPSS 20.0 software was employed for this analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic data

The cohort included 29 patients with rGB and the following distribution: 17 (58.6%) male with a median 50 years of age (range: 28–65 years); and 12 (41.4%) female with a median 50.5 years of age (range: 27–61 years). Fifteen patients formed the LCD/POH group (8 males; 58.3%). The POH group included 14 patients (9 males; 64.3%).

Survival profile

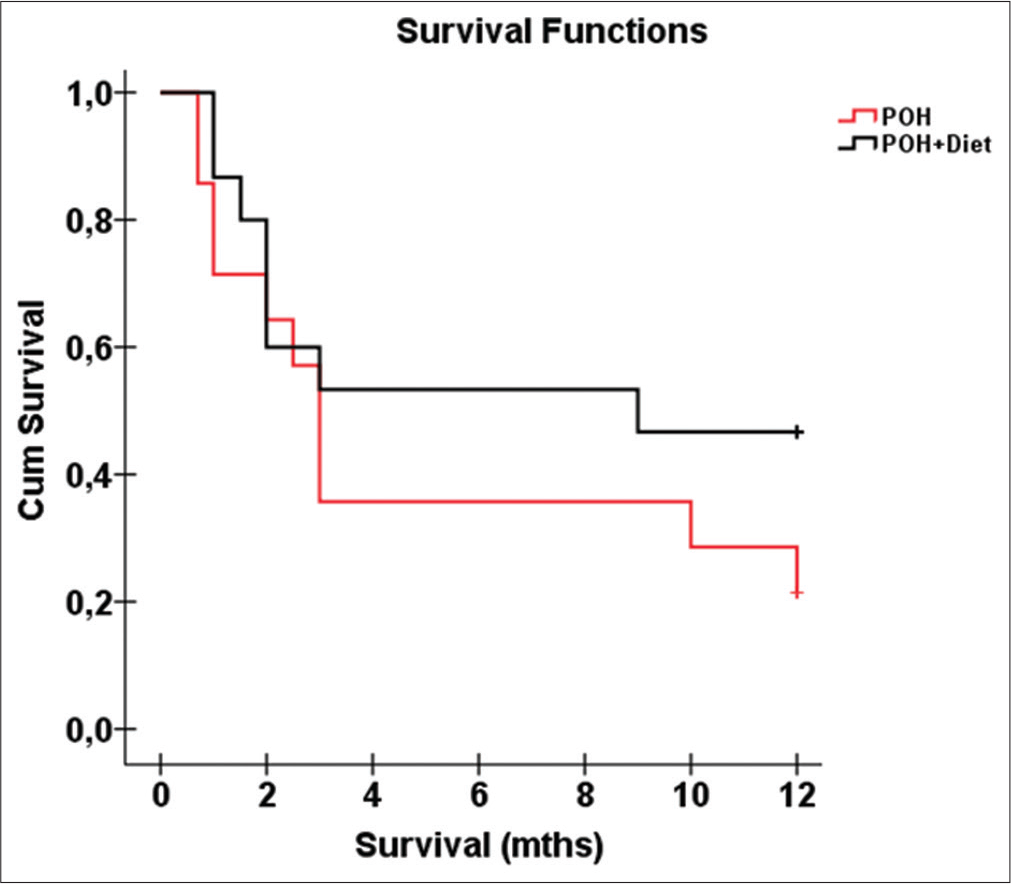

Kaplan–Meier survival plot during the 1-year follow-up period showed that near the 3rd month rGB subjects in the LCD/POH group had a better evolution in comparison to the POH group, although the log rank statistical test did not provide statistical significance between the two groups (P = 0.232;

Disease course according to interventional strategies

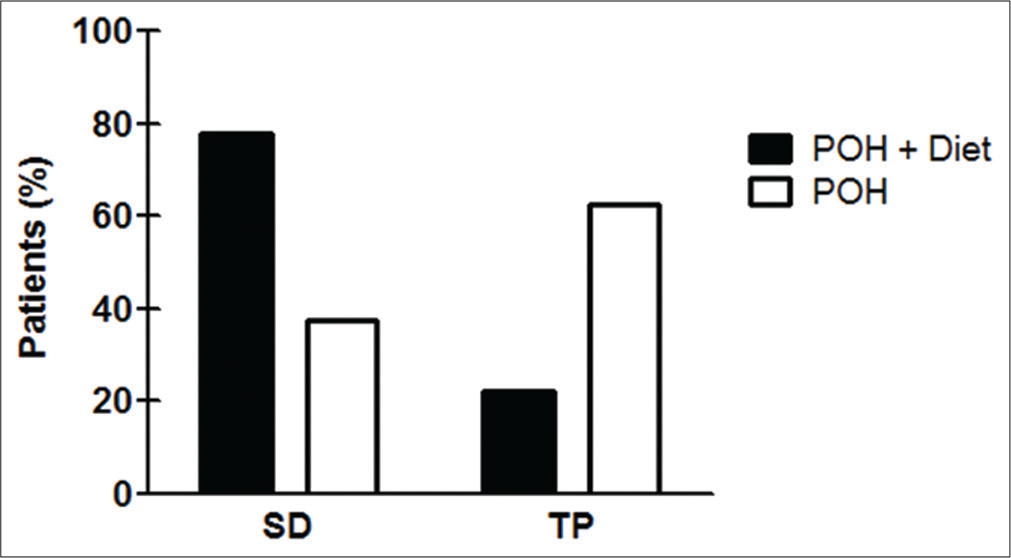

After 1 year of follow-up, the disease course was documented. Among the 15 patients in the LCD/POH group, seven (46.6%) showed stable disease (SD), two (13.3%) showed tumor progression (TP), and six (40%) deceased. Among the 14 patients in the POH group, SD was observed in three (21.4%), TP was verified in five (35.7%), and six (42.9%) succumbed to disease. It was also noticed that 46.6% (n = 7) of patients in the LCD/POH group showed a 2.17-fold increase in the proportion of SD, compared to 21.4% (n = 3) of the POH group. Conversely, the proportion of patients with TP (n = 2) in the LCD/POH group was 2.81-fold decreased when compared to the POH group (n = 5) [

Graph 2:

Effect of the diet in recurrent glioblastoma (rGB) patients under perillyl alcohol (POH) therapy. Compared to POH group with only intranasal POH therapy, LCD/POH group caused a 2.07-fold increase in the proportion of patients with stable disease and 2.81-fold reduction in the proportion of rGB patients with tumor progression.

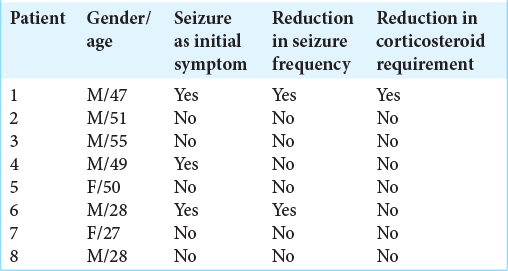

Corticosteroid requirement and seizure frequency in treatment groups

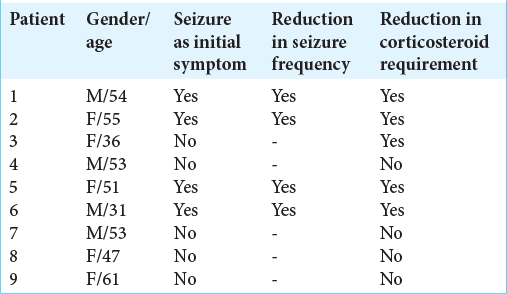

Treatment with high-dose corticosteroids is often required to minimize development of cerebral edema as the main life-threatening complication for rGB patients. In our study, combined POH and LCD decreased the necessity for high-dose steroid treatment, and as a result rGB patients received just maintenance doses. At the time of initial recurrence, that is, at the onset of our study, therapy with high-dose dexamethasone (16 mg/day) was not significantly different between the two groups. However, 3 months after the initiation of our study, the requirement for dexamethasone sharply decreased (to 8 mg/day) in 33.3% (n = 5) patients in the LCD/POH group, as compared to 7.14% (n = 1) patients in the POH group. Thus, there was a 4.66 times greater dose-reduction benefit in the group of patients undergoing LCD/ POH combination treatment. Such patients further showed improvement of clinical status and a reduction of tumor size and peritumoral edema based on MRI, although not all patients responded favorably [

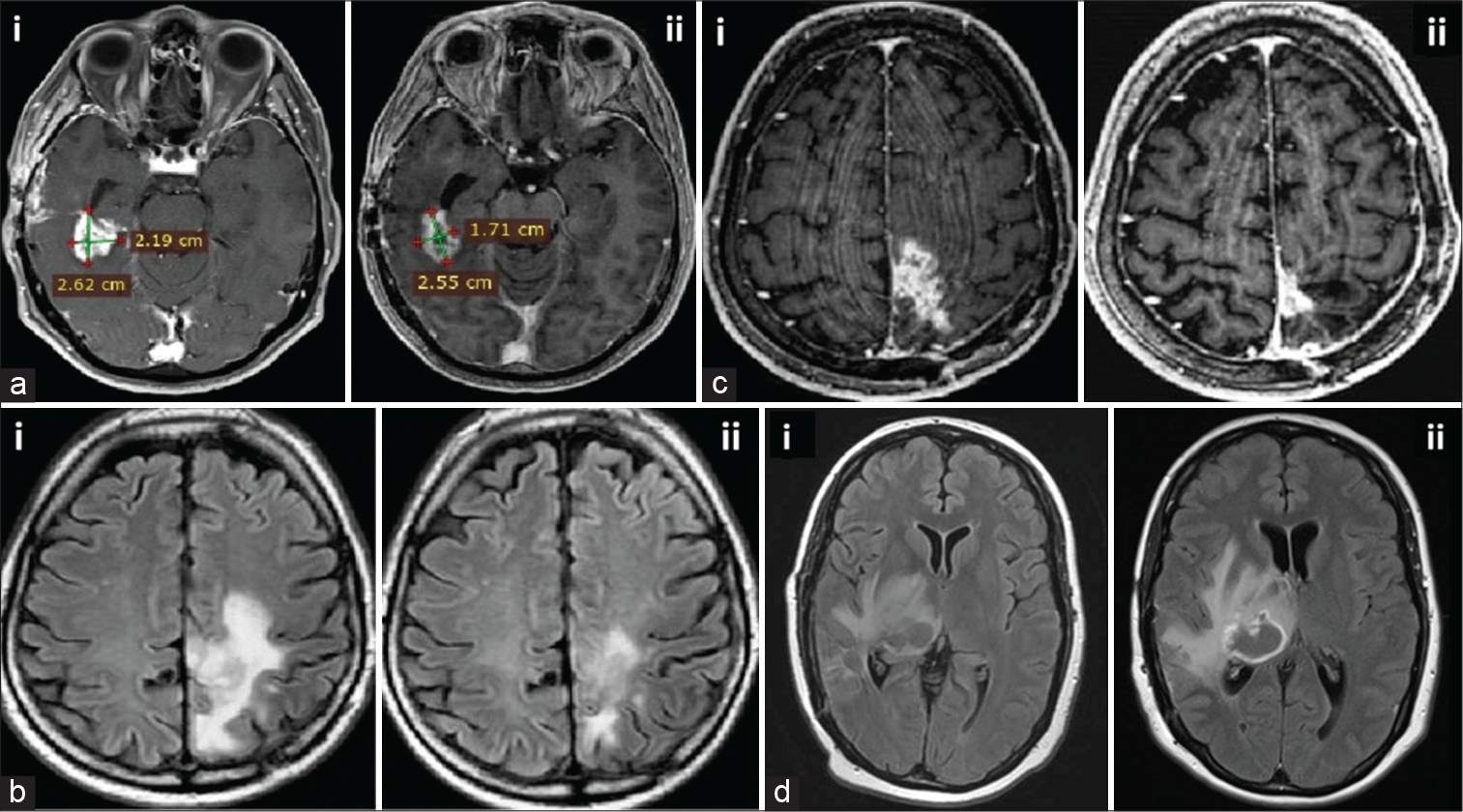

Figure 1:

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs) of representative patients before and after treatment. (a-d) shows MRIs from four different patients (all treated with intranasal perillyl alcohol concomitant with low-carbohydrate diet) that were taken before (left image labeled “i”) and after (right image labeled “ii”) treatment. (a) MRI scan after 12 months of treatment (ii) shows 24% reduction of tumor size (4.36 cm2 total area) as compared to the image obtained before the treatment (5.74 cm2, i). (b and c) Additional examples of patients responding favorably to treatment, with reduction in tumor size after treatment (ii) as compared to the MRIs before treatment (i). (d) Example of patient not responding to treatment. First image (i; axial FLAIR) shows an expansive oval, isointense lesion in the right thalamus, with perilesional edema, causing a mass effect with distortion of the posterior horn of the right lateral ventricle, and slight compression of the third ventricle. Four months later, axial FLAIR (ii) shows irregular enhancement, indicating lack of response to treatment.

In our previous clinical studies, we observed that neurological deficits (51%) were the main complaint of rGB patients, including headache (43%) and seizures (24%).[

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to assess during a 1-year follow-up the effect of a low carbohydrate diet concomitant with intranasal POH for rGB patients. It showed that this strategy: (a) Reduced seizure frequency; (b) decreased the proportion of patients who required corticosteroid treatment; (c) reduced tumor size and peritumoral edema; and (d) improved clinical condition with further beneficial outcomes for rGB patients. These promising results are encouraging because currently available protocols for rGB are associated with reduced OS and worsened quality of life, failing to achieve meaningful results in clinical trials.[

rGB represents the greatest challenge for neuro-oncological practice. Current treatments lack effective protocols for therapeutic conduct and have a propensity for high rate of complications. Indeed, several agents used for the treatment of rGB alone or in combination, failed to achieve meaningful results in clinical trials.[

The present study was conducted to assess toxicity, as well as aspects of quality of life, in rGB patients under continuous intranasal POH therapy with concomitant tumor metabolism-targeted diet over a 1-year period. We observed an early two-fold increment in the proportion of rGB patients with SD, and nearly three-fold decrease in the proportion of TP among patients with POH+LCD, when compared to POH inhalation therapy alone. Such findings suggest an adjuvant effect of LCD combined with inhaled POH on halting TP.

While consistent adherence to the LCD can become a limiting factor over an extended period of time, the reduction in steroid dose and lower frequency of seizures generally contributes to the improvement of quality of life.[

Kaplan–Meier plot of LCD/POH group showed an increased probability of survival when compared to POH group with single inhaled therapy [

Of note, we observed that rGB patients with reduced requirements for high corticosteroid therapy and anticonvulsant drugs had SD and low morbidity with improved clinical condition, mainly due to the treatment-related toxicities. In fact, intranasal POH+LCD halted TP, with almost 24% of tumor area reduction during 1-year of therapy adherence [

Frequently, rGB patients present with deficits in brain areas controlling executive functioning and coordination, which impacts quality of life and requires costly integral home assistance. There is limited information on the humanistic burden among rGB patients; we, therefore, established parameters related to general improvement of conditions associated with reduced corticosteroid requirement and frequency of seizures as a reflection of overall quality of life.[

In consonance with our results, preclinical models have shown glioma growth inhibition with low carbohydrate diet.[

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro under Grant (E-26/110.329/2011; E-26/110.948/2013); FundaçãoEuclides da Cunha (FEC 3662 – Contract UFF 055/2015), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal do Ensino Superior (CAPES) providing scholarship.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the support given by the Clinical Research Unit (UPC/HUAP) providing the appropriate structure for patient care. JSG and GMF were affiliated with PhD postgraduate programs Ciencias Medicas (JSG), and Neurologia (GMF) of the Faculty of Medicine at the Universidade Federal Fluminense.

References

1. Alexander BM, Cloughesy TF. Adult glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017. 35: 2402-9

2. Alexander S, Friedl P. Cancer invasion and resistance: Interconnected processes of disease progression and therapy failure. Trends Mol Med. 2012. 18: 13-26

3. Asrih M, Altirriba J, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Jornayvaz FR. Ketogenic diet impairs FGF21 signaling and promotes differential inflammatory responses in the liver and white adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2015. 10: e0126364

4. Bao Z, Chen K, Krepel S, Tang P, Gong W, Zhang M. High glucose promotes human glioblastoma cell growth by increasing the expression and function of chemoattractant and growth factor receptors. Transl Oncol. 2019. 12: 1155-63

5. Chaichana KL, McGirt MJ, Woodworth GF, Datoo G, Tamargo RJ, Weingart J. Persistent outpatient hyperglycemia is independently associated with survival, recurrence and malignant degeneration following surgery for hemispheric low grade gliomas. Neurol Res. 2010. 32: 442-8

6. Chambless LB, Parker SL, Hassam-Malani L, McGirt MJ, Thompson RC. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity are independent risk factors for poor outcome in patients with high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2012. 106: 383-9

7. Champ CE, Palmer JD, Volek JS, Werner-Wasik M, Andrews DW, Evans JJ. Targeting metabolism with a ketogenic diet during the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2014. 117: 125-31

8. Chen Z, Xu N, Zhao C, Xue T, Wu X, Wang Z. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy vs single-agent therapy in recurrent glioblastoma: Evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer Manag Res. 2018. 10: 2193-205

9. Cho HY, Wang W, Jhaveri N, Torres S, Tseng J, Leong MN. Perillyl alcohol for the treatment of temozolomide-resistant gliomas. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012. 11: 2462-72

10. da Fonseca CO, Silva JT, Lins IR, Simao M, Arnobio A, Futuro D. Correlation of tumor topography and peritumoral edema of recurrent malignant gliomas with therapeutic response to intranasal administration of perillyl alcohol. Invest New Drugs. 2009. 27: 557-64

11. da Fonseca CO, Simao M, Lins IR, Caetano RO, Futuro D, Quirico-Santos T. Efficacy of monoterpene perillyl alcohol upon survival rate of patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011. 137: 287-93

12. da Fonseca CO, Teixeira RM, Silva JT, Fischer JG, Meirelles OC, Landeiro JA. Long-term outcome in patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with perillyl alcohol inhalation. Anticancer Res. 2013. 33: 5625-31

13. Fajardo NM, Meijer C, Kruyt FA. The endoplasmic reticulum stress/unfolded protein response in gliomagenesis, tumor progression and as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016. 118: 1-8

14. Ge JJ, Li C, Qi SP, Xue FJ, Gao ZM, Yu CJ. Combining therapy with recombinant human endostatin and cytotoxic agents for recurrent disseminated glioblastoma: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2020. 20: 24

15. Gershuni VM, Yan SL, Medici V. Nutritional ketosis for weight management and reversal of metabolic syndrome. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018. 7: 97-106

16. Gomes AC, Mello AL, Ribeiro MG, Garcia DG, da Fonseca CO, Salazar MD. Perillyl alcohol, a pleiotropic natural compound suitable for brain tumor therapy, targets free radicals. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2017. 65: 285-97

17. Gupta K, Burns TC. Radiation-induced alterations in the recurrent glioblastoma microenvironment: Therapeutic implications. Front Oncol. 2018. 8: 503

18. Happold C, Gorlia T, Chinot O, Gilbert MR, Nabors LB, Wick W. Does valproic acid or levetiracetam improve survival in glioblastoma? A pooled analysis of prospective clinical trials in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2016. 34: 731-9

19. Hironori K, Hideki N. Stress responses from the endoplasmic reticulum in cancer. Front Oncol. 2015. 5: 93

20. Jelluma N, Yang X, Stokoe D, Evan GI, Dansen TB, Haas-Kogan HA. Glucose withdrawal induces oxidative stress followed by apoptosis in glioblastoma cells but not in normal human astrocytes. Mol Cancer Res. 2006. 4: 319-30

21. Johnson GG, White MC, Grimaldi M. Stressed to death: Targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress response induced apoptosis in gliomas. Curr Pharm Des. 2011. 17: 284-92

22. Lara-Velazquez M, Al-Kharboosh R, Jeanneret S, VazquezRamos C, Mahato D, Tavanaiepour D. Advances in brain tumor surgery for glioblastoma in adults. Brain Sci. 2017. 7: 166

23. Lawrence YR, Blumenthal DT, Matceyevsky D, Kanner AA, Bokstein F, Corn BW. Delayed initiation of radiotherapy for glioblastoma: How important is it to push to the front (or the back) of the line?. J Neurooncol. 2011. 105: 1-7

24. Marsh J, Mukherjee P, Seyfried TN. Drug/diet synergy for managing malignant astrocytoma in mice: 2-deoxy-D-glucose and the restricted ketogenic diet. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008. 5: 33

25. McDonald JT, Gao X, Steber C, Breed JL, Pollock C, Ma L. Host mediated inflammatory influence on glioblastoma multiforme recurrence following high-dose ionizing radiation. PLoS One. 2017. 12: e0178155

26. Mulrooney TJ, Marsh J, Urits I, Seyfried TN, Mukherjee P. Influence of caloric restriction on constitutive expression of NF-κB in an experimental mouse astrocytoma. PLoS One. 2011. 6: e18085

27. Pellerino A, Franchino F, Soffietti R, Rudà R. Overview on current treatment standards in high-grade gliomas. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018. 62: 225-38

28. Poff A, Koutnik AP, Egan KM, Sahebjam S, D’Agostino D, Kumar NB. Targeting the Warburg effect for cancer treatment: Ketogenic diets for management of glioma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017. 56: 135-48

29. Santos JG, da Cruz WM, Schönthal AH, Salazar MD, Fontes CA, Quirico-Santos T. Efficacy of a ketogenic diet with concomitant intranasal perillyl alcohol as a novel strategy for the therapy of recurrent glioblastoma. Oncol Lett. 2018. 15: 1263-70

30. Schönthal AH, Chen TC, Hofman FM, Louie SG, Petasis NA. Preclinical development of novel anti-glioma drugs targeting the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Curr Pharm Des. 2011. 17: 2428-38

31. Seyfried TN, Kiebish MA, Marsh J, Shelton LM, Huysentruyt LC, Mukherjee P. Metabolic management of brain cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011. 1807: 577-94

32. Seystahl K, Wick W, Weller M. Therapeutic options in recurrent glioblastoma-an update. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016. 99: 389-408

33. Signorovitch J, Li N, Ohashi E, Dastani H, Shaw J, Orsini L. Overall survival (OS), quality of life (QOL), and neurocognitive function (NF) in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): A systematic literature review. Value Health. 2015. 18: A433

34. Taunk NK, Moraes FY, Escorcia FE, Mendez LC, Beal K, Marta GN. External beam re-irradiation, combination chemoradiotherapy, and particle therapy for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016. 16: 347-58

35. Toledo M, Sarria-Estrada S, Quintana M, Maldonado X, Martinez-Ricarte F, Rodon J. Epileptic features and survival in glioblastomas presenting with seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2017. 130: 1-6

36. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956. 123: 309-14

37. Wen PY, Schiff D. Valproic acid as the AED of choice for patients with glioblastoma? The jury is out. Neurology. 2011. 77: 1114-5