- 6th Orthopedic Department, KAT Hospital, Athens, Greece

- Department of Scoliosis and Spine, KAT General Hospital, Athens, Greece

- Department of Surgery, Metaxa Cancer Memorial Hospital, Pireus, Greece

- Department of Orthopedics, Athens Medical Center, Athens, Greece

- Department of Orthopedics, Laiko General Hospital of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Correspondence Address:

Konstantinos Zygogiannis, Department of Scoliosis and Spine, KAT General Hospital, Athens, Greece.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_232_2024

Copyright: © 2024 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Konstantinos Manolakos1, Konstantinos Zygogiannis2, Othon Manolakos3, Chagigia Mousa4, Georgios Papadimitriou4, Ioannis Fotoniatas5. Anatomical variations of ilioinguinal nerve: A systematic review of the literature. 05-Jul-2024;15:225

How to cite this URL: Konstantinos Manolakos1, Konstantinos Zygogiannis2, Othon Manolakos3, Chagigia Mousa4, Georgios Papadimitriou4, Ioannis Fotoniatas5. Anatomical variations of ilioinguinal nerve: A systematic review of the literature. 05-Jul-2024;15:225. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=12983

Abstract

Background: Several anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve branches have been recorded in older studies. Knowledge of these variations is useful for the improvement of peripheral nerve blocks and avoidance of iatrogenic nerve injuries during abdominal surgeries. The purpose of this study is to perform a systematic review of the literature about the anatomical topography and variations of the ilioinguinal nerve.

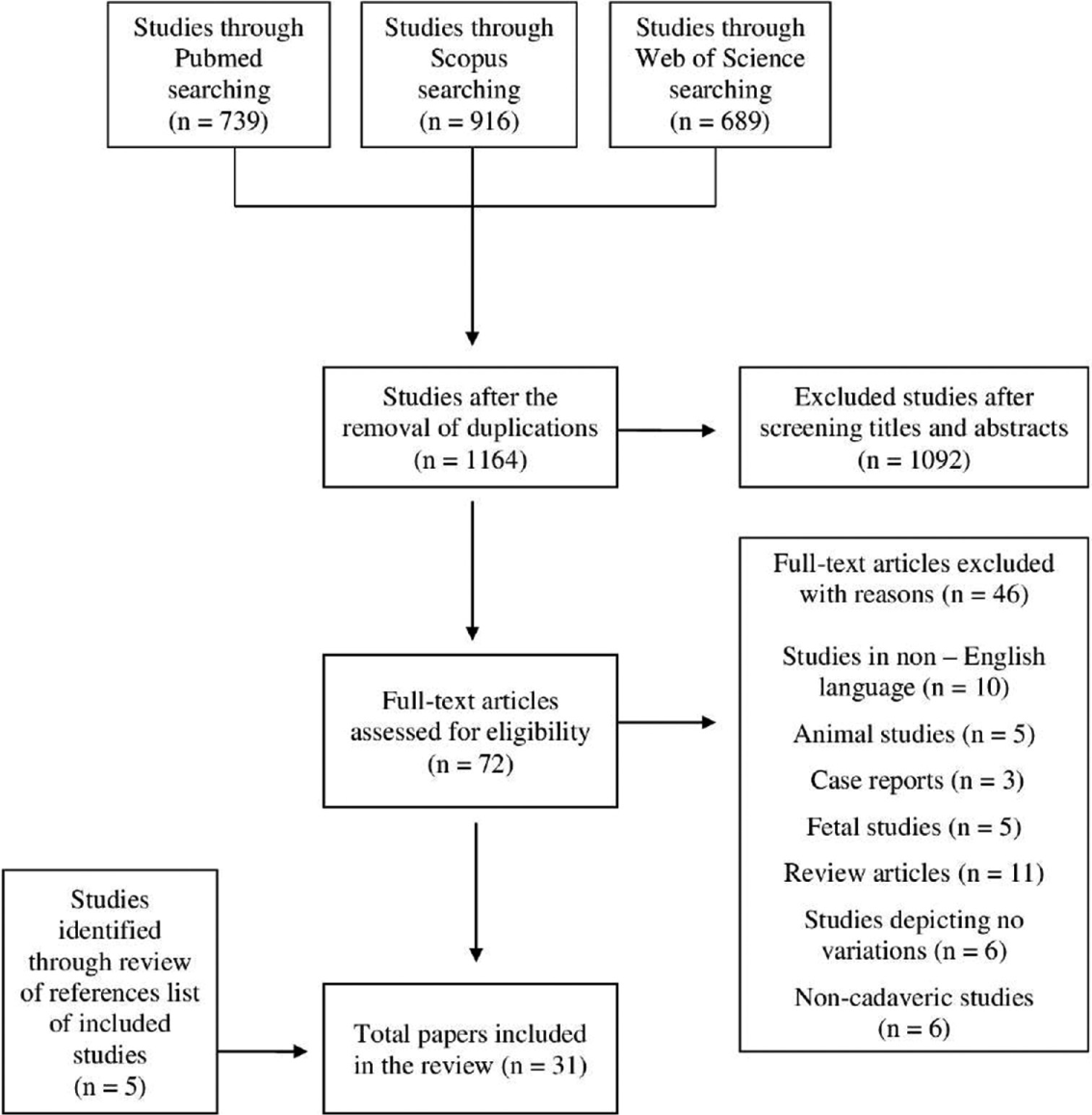

Methods: An extensive search in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science electronic databases was conducted by the first author in November 2021, with the use of the PRISMA guidelines. Anatomical or cadaveric studies about the origin, the course, and the distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve were included in this review. Thirty-one cadaveric studies were included for qualitative analysis.

Results: Several anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve were depicted including its general properties, its origin, its branching patterns, its course, its relation to anatomical landmarks, and its termination. Among them, the absence of ilioinguinal nerve ranged from 0% to 35%, its origin from L1 ranged from 65% to 100%, and its isolated emergence from psoas major ranged from 47% to 94.5%. Numerous anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve exist, not commonly cited in classic anatomical textbooks. The branches of the ilioinguinal nerve may be damaged during spinal anesthesia and surgical procedures in the lower abdominal region.

Conclusion: Therefore, a better understanding of the regional anatomy and its variations is of vital importance for the prevention of ilioinguinal nerve injuries.

Keywords: Anatomical variations, Iliohypogastric nerve, Ilioinguinal nerve, Lumbar plexus

INTRODUCTION

The ilioinguinal nerve is the 2nd nerve of the lumbar plexus. It derives from the anterior branch of the 1st lumbar nerve (L1), usually after the administration of an anastomotic branch to the anterior branch of the 2nd lumbar nerve (L2), and occasionally with the contribution of the 12th thoracic nerve (T12). In parallel and below the iliohypogastric nerve, the ilioinguinal nerve emerges from the lateral border of the psoas muscle, anterior to quadratus lumborum muscle, behind the renal fossa, into the kidney fat, behind the lower pole of the kidney.[

Between the middle and anterior third of the iliac crest, the ilioinguinal nerve perforates the aponeurosis of the transverse abdominal muscle and runs anterior, almost tangential to the iliac crest, between the two oblique abdominal muscles.[

In surgeries around the groin area, the ilioinguinal nerve blockade provides effective perioperative pain control[

METHODS

An extensive search in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science electronic databases was conducted by the first author in November 2021, with the use of the PRISMA guidelines.[

Anatomical or cadaveric studies about the origin, the course, and the distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve were included in this review. Exclusion criteria were (a) study protocols, case reports, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, (b) studies in non-English language or without available full text, and (c) non-human studies.

RESULTS

The initial search revealed 2344 studies [

General properties

As shown in

Origin

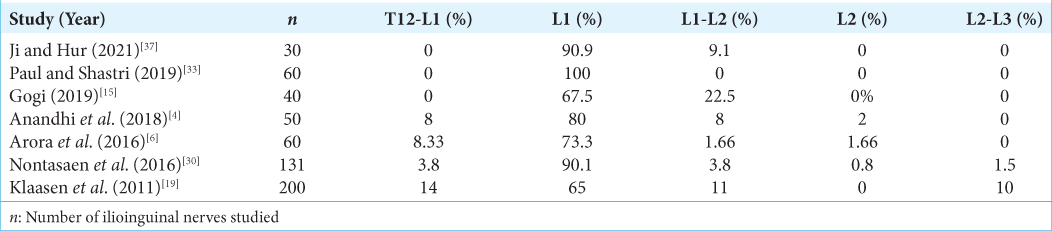

The origin of the ilioinguinal nerve has shown great variability. It is known that the iliohypogastric nerve is mainly derived from L1, with the occasional contribution from L2 to T12.[

Branching patterns

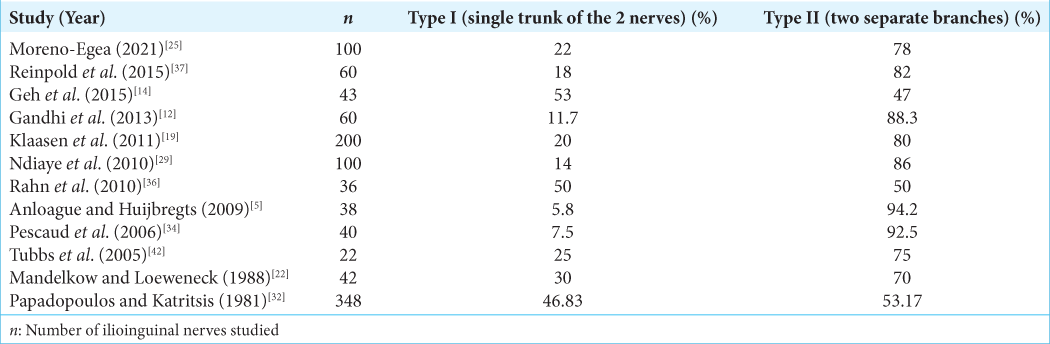

The ilioinguinal nerve may emerge from the outer border of the psoas muscle, either united with a common trunk with the iliohypogastric nerve (Type I) or, most commonly, as a separate nerve (Type II). As shown in

In the case of a Type I branching pattern, the division of the iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerve may be located behind the kidney or between the internal oblique muscle and the transverse abdominal muscle.[

In the case of the Type II branching pattern, according to Moreno-Egea, the ilioinguinal nerve emerges from the lateral border of the psoas at a mean distance of 2.5 ± 0.8 cm (range 1.3–4.2 cm), from the iliohypogastric nerve.[

Retroperitoneal course

Almost always, the ilioinguinal nerve courses on the anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum muscle, which is the position with the minimum anatomic variability. According to Gandhi et al., the ilioinguinal nerve was 1.5 cm apart all along its course across the quadratus lumborum muscle.[

Likewise, to the iliohypogastric nerve, the topographic variability of the ilioinguinal nerve increases from dorsally to ventrally. The relation of the nerve with the posterior superior iliac spine is quite variable. According to Reinold et al., in half of the cases, the nerve runs up to 5.0 cm laterally, and the nerve runs up to 1.6 cm medially with respect to the posterior superior iliac spine. Moreover, in about half of cases, the nerve runs up to 5.5 cm cranially, and in half of the cases, the nerve runs up to 4.0 cm caudally to the posterior superior iliac spine. In one case, the ilioinguinal nerve was divided into two branches 5.0 cm laterally from the posterior superior iliac spine. The mean distance of the ilioinguinal nerve to the posterior superior iliac spine is 7.7 ± 1.0 cm cranially.[

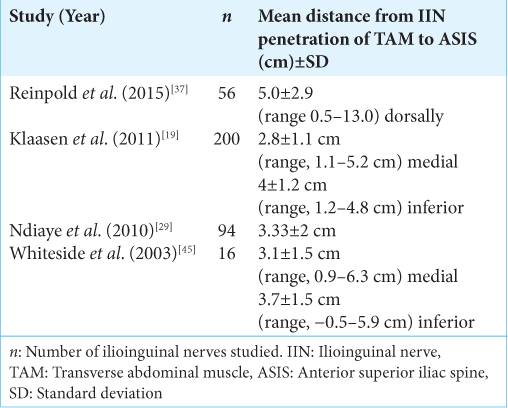

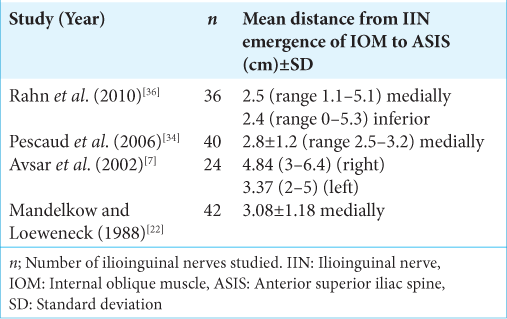

Relation to anterior superior iliac spine

As its course through the abdominal wall is rather oblique, the ilioinguinal nerve lies only 5–6 mm deep to the fascia of the transverse abdominal muscle.[

Relation to inguinal canal

An early study by Moosman and Oelrich in 1977 observed that in 35% of cases, the ilioinguinal nerve followed an aberrant course through the inguinal canal covered by the spermatic cord or the round ligament of the uterus.[

According to Mandelkow and Loeweneck, in the majority of cases (72%), after a short course in the inguinal canal, the ilioinguinal nerve runs medially to the spermatic cord at the superficial inguinal ring. At 10% of the specimen, it passes lateral to the spermatic cord or the round ligament. In the rest of the cases (18%), the ilioinguinal nerve perforates the deep fascia of the external oblique muscle 1–2 cm above the superficial inguinal ring.[

According to Ndiaye et al., in 78.7% of cases, the ilioinguinal nerve travels anterior to the spermatic cord toward the superficial inguinal ring. In 2.12% of cases, the ilioinguinal nerve perforated prematurely the fascia without any connection to the spermatic cord.[

Termination

The ilioinguinal nerve is known to supply the sensory innervation of the pubic symphysis, the anterior surface of the scrotum in men, the labia majora in women, and the superomedial area of the thigh. According to Akita et al., the incidence of this pattern of the sensory distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve was 90.7%. In 13% of these cases, the genitofemoral nerve contributed to the sensory innervation of these four regions.[

Two studies by Ndiaye et al. have evaluated the terminal distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve.[

The genital branches of the ilioinguinal and the iliohypogastric nerve may be either distinct or fused to constitute a common trunk. In 60% of cases, the distal portions of the iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerve are united to a single genital branch.[

The mean distance of the termination of the ilioinguinal nerve from the midline has been measured in three studies. According to Klaasen et al., this mean distance is 3 ± 0.5 cm (range, 2.2–5.3 cm) lateral.[

DISCUSSION

The anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve are plentiful in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review attempting to record all the anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve in relation to its properties, its origin, its branching patterns, its course, its relation to anatomical landmarks, and its termination.

The knowledge of the anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve is significant in lower abdomen operations, regional anesthesia, and nerve entrapment syndromes. The branches of the ilioinguinal nerve are closely related to surgical approaches in the lower abdomen below the superior anterior iliac spine and may be damaged at skin incisions or trauma suturing, causing nerve entrapment.[

It has been reported that the frequency of failure of ilioinguinal nerve blockades is 10–25%.[

In the present review, the reported incidence of complete absence of ilioinguinal nerve is up to 35%. In case of complete absence of the ilioinguinal nerve, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve may compensate for the sensory innervations. This variation should be suspected when the nerve is not found under the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, and special attention is required during the approach of the cremaster muscles and the dissection of the herniated sac.

Most commonly, the ilioinguinal nerve derives from the L1 root with or without the contribution of L2 and T12. However, in literature, sensory fibers composing the ilioinguinal nerve encompass a region of the spinal cord extending from T12 to L3. The nerve may emerge from the psoas major, united with the iliohypogastric nerve, but most commonly (47–94%), it arises separately as a single nerve. The two nerves may initially rise separately and communicate at the iliac crest. All these complicated origins, interconnections, and anastomoses of the branches of the ilioinguinal nerve may result in sensory overlap or provoke chronic spontaneous neuropathies and failures and complications regarding their blockades.[

The retroperitoneal course of the ilioinguinal nerve also contains certain variations. Studies reporting its relation to the posterior superior iliac spine have shown contradictory results.[

The ilioinguinal nerve may travel variably through the inguinal canal, with a variable relation to the spermatic cord or the round ligament, either as a single trunk or united with branches of the iliohypogastric nerve.[

The variability of the course of the ilioinguinal nerve continues at its terminal branches. These may present as a single trunk or may divide prematurely in the inguinal area into collateral and terminal branches distributed in the scrotal, pubic, or femoral regions. As the terminal branches of the ilioinguinal nerve usually begin below the inguinal canal, they are at risk of injury during the dissection of the spermatic cord. Taking this diversity into consideration, Ndiaye et al. suggested the performance of an ilioinguinal block with the use of superficial and easily palpable landmarks at 1 cm of the inguinal ligament and 3.3 cm of the anterior superior iliac spine.[

CONCLUSION

The results of the present review revealed numerous anatomical variations of the ilioinguinal nerve in number, path, and method of termination, not commonly cited in classic anatomical textbooks. These atypical locations of the ilioinguinal nerve may predispose to a higher rate of injury, resulting in postoperative pain. The knowledge of these variations may prevent damage during repairs of groin hernias and the postoperative complication of inguinodynia. Moreover, it may help in understanding the etiology and the surgical aspects of neuropathies of the groin. The branches of the ilioinguinal nerve may be damaged during spinal anesthesia and the anatomic variability of the nerve may cause failures of the blockade of the nerve. Further studies delineating ilioinguinal nerve topography variation may increase the success of nerve blockades in abdominal surgical procedures and decrease the possibility of ilioinguinal nerve injuries.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

Acknowledgment

We state that Manolakos Konstantinos and Manolakos Othon have seen and can confirm the authenticity of the raw data.

References

1. Akita K, Niga S, Yamato Y, Muneta T, Sato T. Anatomic basis of chronic groin pain with special reference to sports hernia. Surg Radiol Anat. 1999. 21: 1-5

2. Al-Dabbagh A. Anatomical variations of the inguinal nerves and risks of injury in 110 hernia repairs. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002. 24: 102-7

3. Amin N, Krashin D, Trescot AM, editors. Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve entrapment: Abdominal. Peripheral nerve entrapments: Clinical diagnosis and management. United States: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 413-24

4. Anandhi PG, Alagavenkatesan VN, Pushpa P, Shridharan P. A study to document the formation of lumbar plexus, its branching pattern, variations and its relation with psoas major muscle. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2013. 5: K20-3

5. Anloague PA, Huijbregts P. Anatomical variations of the lumbar plexus: A descriptive anatomy study with proposed clinical implications. J Man Manip Ther. 2009. 17: e107-14

6. Arora D, Trehan SS, Kaushal S, Chhabra U. Morphology of lumbar plexus and its clinical significance. Int J Anat Res. 2016. 4: 2007-14

7. Avsar FM, Sahin M, Arikan BU, Avsar AF, Demirci S, Elhan A. The possibility of nervus ilioinguinalis and nervus iliohypogastricus injury in lower abdominal incisions and effects on hernia formation. J Surg Res. 2002. 107: 179-85

8. Cardenas-Trowers OO, Bergden JS, Gaskins JT, Gupta AS, Francis SL, Herring NR. Development of a safety zone for rectus abdominis fascia graft harvest based on dissections of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. 222: 480.e1-7

9. Cardosi RJ, Cox CS, Hoffman MS. Postoperative neuropathies after major pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002. 100: 240-4

10. Craven J. Lumbar and sacral plexuses. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2004. 5: 108

11. Ellis H. Anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal canal. Anaesth Intensive Care Med. 2009. 10: 315-7

12. Gandhi KR, Joshi SD, Joshi SS, Siddiqui AU, Jalaj AV. Lumbar plexus and its variations. J Anat Soc India. 2013. 62: 47-51

13. Gofeld M, Christakis M. Sonographically guided ilioinguinal nerve block. J Ultrasound Med. 2006. 25: 1571-5

14. Geh N, Schultz M, Yang L, Zeller J. Retroperitoneal course of iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves: A study to improve identification and excision during triple neurectomy. Clin Anat. 2015. 28: 903-9

15. Gogi P. A study of variations in iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves in human adults. Int J Anat Res. 2019. 7: 6727-31

16. Izci Y, Gürkanlar D, Ozan H, Gönül E. The morphological aspects of lumbar plexus and roots. An anatomical study. Turk Neurosurg. 2005. 15: 87-92

17. Jacobs CJ, Steyn WH, Boon JM. Segmental nerve damage during a McBurney’s incision: A cadaveric study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004. 26: 66-9

18. Ji HJ, Hur MS. Morphometry of spinal nerve composition and thicknesses of lumbar plexus nerves for use in clinical applications. Int J Morphol. 2021. 39: 1006-11

19. Klaassen Z, Marshall E, Tubbs RS, Louis RG, Wartmann CT, Loukas M. Anatomy of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves with observations of their spinal nerve contributions. Clin Anat. 2011. 24: 454-61

20. Luijendijk RW, Jeekel J, Storm RK, Schutte PJ, Hop WC, Drogendijk AC. The low transverse Pfannenstiel incision and the prevalence of incisional hernia and nerve entrapment. Ann Surg. 1997. 225: 365-9

21. Maigne JY, Maigne R, Guérin-Surville H. Anatomic study of the lateral cutaneous rami of the subcostal and iliohypogastric nerves. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986. 8: 251-6

22. Mandelkow H, Loeweneck H. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. Distribution in the abdominal wall, danger areas in surgical incisions in the inguinal and pubic regions and reflected visceral pain in their dermatomes. Surg Radiol Anat. 1988. 10: 145-9

23. Mirilas P, Skandalakis JE. Surgical anatomy of the retroperitoneal spaces, Part IV: Retroperitoneal nerves. Am Surg. 2010. 76: 253-62

24. Mirjalili SA, editors. Anatomy of the lumbar plexus. Nerves and nerve injuries. Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd.; 2015. p. 609-17

25. Moreno-Egea A. A study to improve identification of the retroperitoneal course of iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, femorocutaneous and genitofemoral nerves during laparoscopic triple neurectomy. Surg Endosc. 2021. 35: 1116-25

26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009. 6: e1000097

27. Moosman DA, Oelrich TM. Prevention of accidental trauma to ilioinguinal nerve during inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg. 1977. 133: 146-8

28. Ndiaye A, Diop M, Ndoye JM, Konate I, Ndiaye AI, Mane L. Anatomical basis of neuropathies and damage to the ilioinguinal nerve during repairs of groin hernias (about 100 dissections). Surg Radiol Anat. 2007. 29: 675-81

29. Ndiaye A, Diop M, Ndoye JM, Mané L, Nazarian S, Dia A. Emergence and distribution of the ilioinguinal nerve in the inguinal region: applications to the ilioinguinal anaesthetic block (about 100 dissections). Surg Radiol Anat. 2010. 32: 55-62

30. Nontasaen P, Das S, Nisung C, Sinthubua A, Mahakkanukrauh P. A cadaveric study of the anatomical variations of the lumbar plexus with clinical implications. J Anat Soc India. 2016. 65: 24-8

31. Oelrich TM, Moosman DA. Aberrant course of cutaneous component of ilioinguinal nerve. Anat Rec. 1977. 189: 233-6

32. Papadopoulos NJ, Katritsis ED. Some observations on the course and relations of the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves (based on 348 specimens). Anat Anz. 1981. 149: 357-64

33. Paul L, Shastri D. Anatomical variations in formation and branching pattern of the border nerves of lumbar Region. Natl J Clin Anat. 2019. 8: 57-61

34. Peschaud F, Malafosse R, Floch-Prigent PL, Coste-See C, Nordlinger B, Delmas V. Anatomical bases of prolonged ilioinguinal-hypogastric regional anesthesia. Surg Radiol Anat. 2006. 28: 511-7

35. Rab M, Ebmer And J, Dellon AL. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: Implications for the treatment of groin pain. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001. 108: 1618-23

36. Rahn DD, Phelan JN, Roshanravan SM, White AB, Corton MM. Anterior abdominal wall nerve and vessel anatomy: Clinical implications for gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010. 202: 234.e1-5

37. Reinpold W, Schroeder AD, Schroeder M, Berger C, Rohr M, Wehrenberg U. Retroperitoneal anatomy of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: Consequences for prevention and treatment of chronic inguinodynia. Hernia. 2015. 19: 539-48

38. Rosenberger RJ, Loeweneck H, Meyer G. The cutaneous nerves encountered during laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia: New anatomical findings for the surgeon. Surg Endosc. 2000. 14: 731-5

39. Salama J, Sarfati E, Chevrel JP. The anatomical bases of nerve lesions arising during the reduction of inguinal hernia. Anat Clin. 1983. 5: 75-81

40. Stark E, Oestreich K, Wendl K, Rumstadt B, Hagmüller E. Nerve irritation after laparoscopic hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 1999. 13: 878-81

41. Stulz P, Pfeiffer KM. Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Arch Surg. 1982. 117: 324-7

42. Tubbs RS, Salter EG, Wellons JC, Blount JP, Oakes WJ. Anatomical landmarks for the lumbar plexus on the posterior abdominal wall. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005. 2: 335-8

43. van Schoor AN, Boon JM, Bosenberg AT, Abrahams PH, Meiring JH. Anatomical considerations of the pediatric ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005. 15: 371-7

44. Weltz CR, Klein SM, Arbo JE, Greengrass RA. Paravertebral block anesthesia for inguinal hernia repair. World J Surg. 2003. 27: 425-9

45. Whiteside JL, Barber MD, Walters MD, Falcone T. Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 189: 1574-8 discussion 8

46. Wijsmuller AR, Lange JF, Kleinrensink GJ, van Geldere D, Simons MP, Huygen F. Nerve-identifying inguinal hernia repair: A surgical anatomical study. World J Surg. 2007. 31: 414-22

47. Wong AK, Ng AT. Review of ilioinguinal nerve blocks for ilioinguinal neuralgia post hernia surgery. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020. 24: 80