- Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hatyai, Thailand

- Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hatyai, Thailand

Correspondence Address:

Rujimas Khumtong, Departments of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Hatyai, Thailand.

DOI:10.25259/SNI_1079_2024

Copyright: © 2025 Surgical Neurology International This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-Share Alike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, transform, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.How to cite this article: Jarudetch Wichaitum1, Rujimas Khumtong1, Kittipong Riabroi1, Tippawan Liabsuetrakul2. Angiographic morphologies of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms for predicting immediate incomplete occlusion after coil embolization. 07-Mar-2025;16:81

How to cite this URL: Jarudetch Wichaitum1, Rujimas Khumtong1, Kittipong Riabroi1, Tippawan Liabsuetrakul2. Angiographic morphologies of wide-necked cerebral aneurysms for predicting immediate incomplete occlusion after coil embolization. 07-Mar-2025;16:81. Available from: https://surgicalneurologyint.com/?post_type=surgicalint_articles&p=13431

Abstract

BackgroundWide-necked cerebral aneurysms present unique challenges in endovascular treatment, with immediate incomplete occlusion posing significant risks for recurrence and mortality. However, the predictive factors of immediate incomplete occlusion after coil embolization of wide-necked aneurysms have not been identified. Thus, this study aimed to identify specific angiographic morphologies predictive of immediate incomplete occlusion after coil or stent-assisted embolization for wide-necked aneurysms.

MethodsThis retrospective case–control study evaluated all patients diagnosed with cerebral wide-necked aneurysms who underwent endovascular treatment between January 2009 and December 2019. The case was defined as wide-necked aneurysms with immediate incomplete occlusion, while control was defined as those with immediate complete occlusion. The cases and controls were compared in a 1:3 ratio. Angiographic morphologies as the predictors of immediate incomplete occlusion were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression with adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

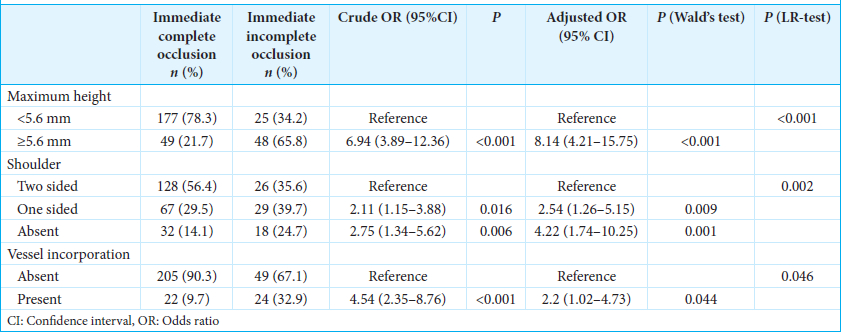

ResultsThere were 73 and 226 cases and controls, respectively. Aneurysm height ≥5.6 mm (aOR, 8.14; 95% CI, 4.21–15.75; P P = 0.001), one-sided shoulder (aOR, 2.54; 95% CI, 1.26–5.15; P = 0.009), and presence of vessel incorporation (aOR, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.02–4.73; P = 0.044) were independent risk factors of immediate incomplete occlusion.

ConclusionAneurysm height ≥5.6 mm, absent two-sided shoulder, and presence of vessel incorporation significantly predict immediate incomplete occlusion after coil embolization for wide-necked aneurysms.

Keywords: Aneurysm, Angiographic, Coil embolization, Morphologies, Occlusion, Predictor, Wide-necked

INTRODUCTION

Unruptured cerebral aneurysms are prevalent in 3.2% of the population[

Wide-necked aneurysms, defined as those with a neck size ≥4 mm, have a significantly lower rate of initial treatment success than narrow-necked aneurysms.[

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, setting, and participants

This retrospective case–control study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of our university and was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

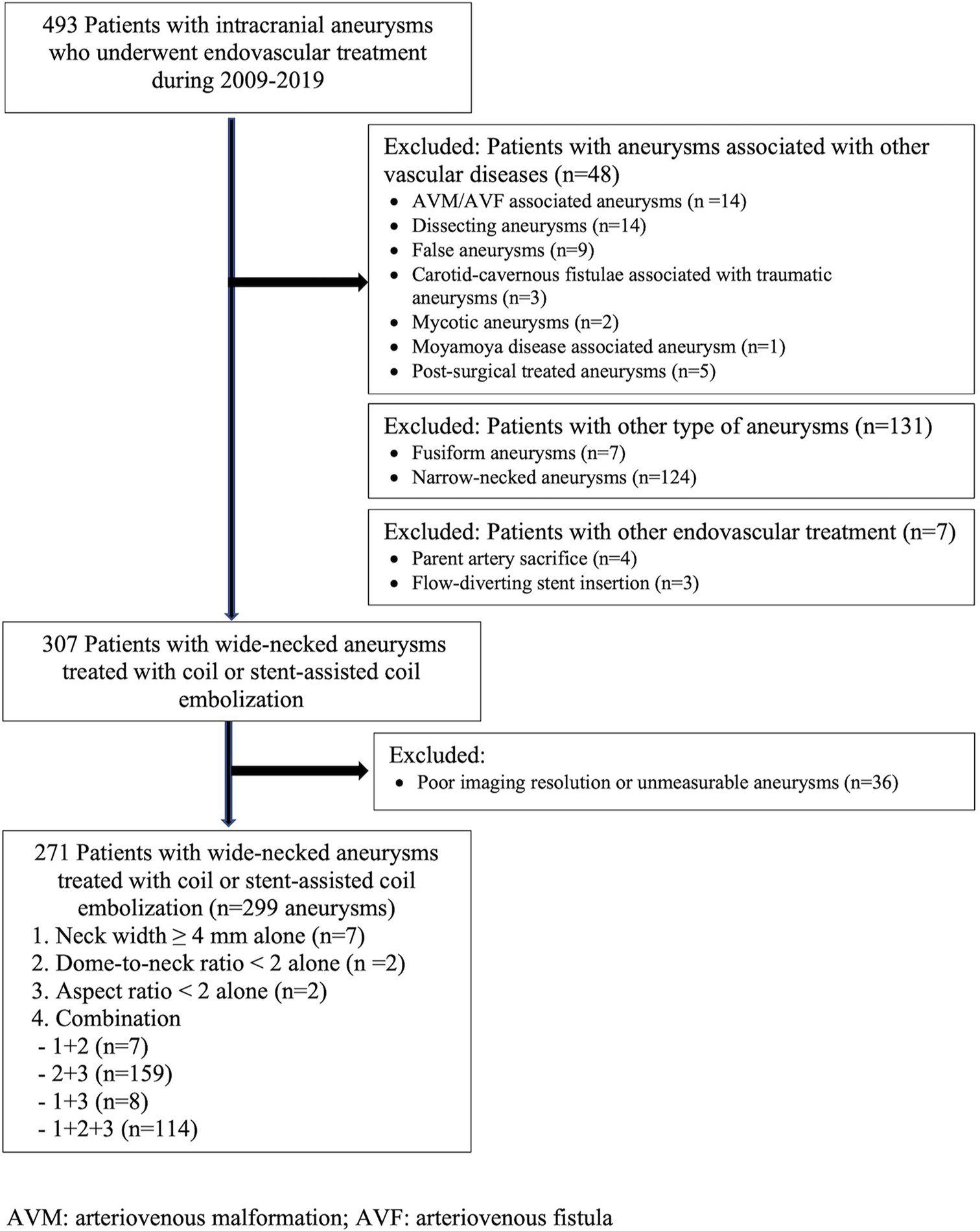

This study was conducted in a main tertiary hospital. All patients diagnosed with cerebral wide-necked aneurysms and who underwent endovascular treatment between January 2009 and December 2019 were evaluated. The patients were identified using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) for cerebral aneurysm, aneurysm of the carotid artery, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. The patient selection flowchart is shown in

The sample size was calculated using two-proportion differences based on the prevalence of two-sided shoulders of wide-necked aneurysms. As there was no similar previous study, we estimated two proportions from the average 67% prevalence rate of absent two-sided shoulder of wide-necked aneurysm from a previous study,[

Study variables

The exposures of interest were the angiographic morphology of wide-necked aneurysm related to the endovascular treatment outcomes, namely, aneurysm height, shape, shoulder, positional type (sidewall and bifurcation),[

The primary outcome measure was the prediction of incomplete occlusion assessed immediately after coil embolization using 2D or 3D angiograms. The degree of occlusion was defined according to the modified Raymond– Ray classification (MRRC)[

The wide-necked aneurysms were identified from existing data, and the images were retrieved from the Picture Archiving and Communication System. Two neurointerventional radiologists independently assessed all aneurysm images. Inconsistent assessments that ranged from 0% to 2% were discussed until an agreement was achieved.

Coiling embolization procedures

Coil embolization was performed in the in-patient setting using a DSA (Philips Allura Xper FD20/10 or Azurion 7 B20/15, Philips, Best, the Netherlands) under general anesthesia. Matrix (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA), Axium (ev3 Inc., Plymouth, MN/Medtronic, Irvine, CA), or Target (Stryker, Fremont, CA) coils were used depending on the availability at the time of the procedure. The simple coiling technique was attempted first in all wide-necked aneurysms, especially those with a dome-to-neck ratio of >1 or with the presence of an aneurysm shoulder(s). The stent-assisted coiling method using Solitaire (ev3, Irvine, CA) or Neuroform Atlas (Boston Scientific/Target, Fremont, CA) stents were used for wide-necked aneurysms with failure of simple coil embolization, dome-to-neck ratio <1, or absence of aneurysm shoulder. The treatment aim was complete occlusion or densely packed aneurysms. Post-embolization angiographies on working projection views were routinely performed to determine the occlusion result. A team of neuro-interventionists performed each treatment procedure.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies with percentages. All exposures were considered as initial predictors and tested for their predictive ability for immediate incomplete occlusion. As no standard cutoff value for aneurysm height was established, we identified the optimal cut-off for aneurysm occlusion using the Youden method. Univariate analysis was used to determine the factors significantly associated with immediate incomplete occlusion. Significant variables in the univariate analysis (i.e., those with P < 0.2) were included in the unadjusted multivariable logistic regression model. A multivariable logistic regression with a stepwise backward method was used for identifying the independent predictors of immediate incomplete occlusion. Interactions of treatment modality with final significant predictors were also tested. The discriminating ability of the model was evaluated according to the goodness of fit with area under the curve (AUC). All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

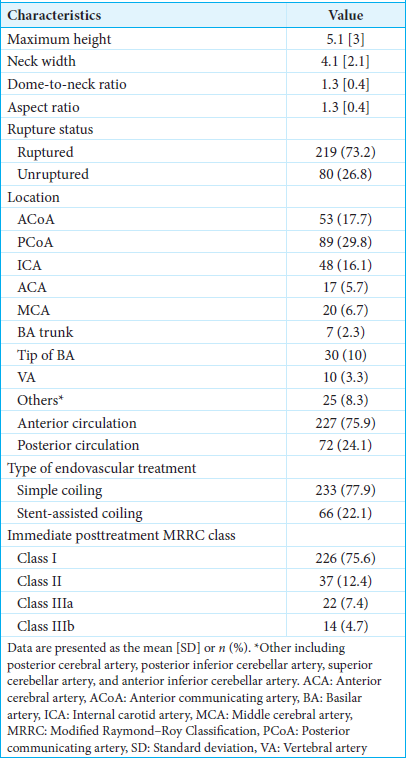

Among the 493 patients with intracranial aneurysms who underwent endovascular treatment during the 10-year study period, 307 patients had wide-necked aneurysms treated with coil or stent-assisted coil embolization. Of them, 36 patients who had poor imaging resolution or unmeasurable aneurysms were excluded from the study. Finally, 271 patients (average age, 62.5 ± 13.2 years; females, 71.6%) were evaluated. A total of 299 wide-necked aneurysms treated with coil embolization or stent-assisted coil embolization were analyzed. The characteristics of the wide-necked aneurysms are described in

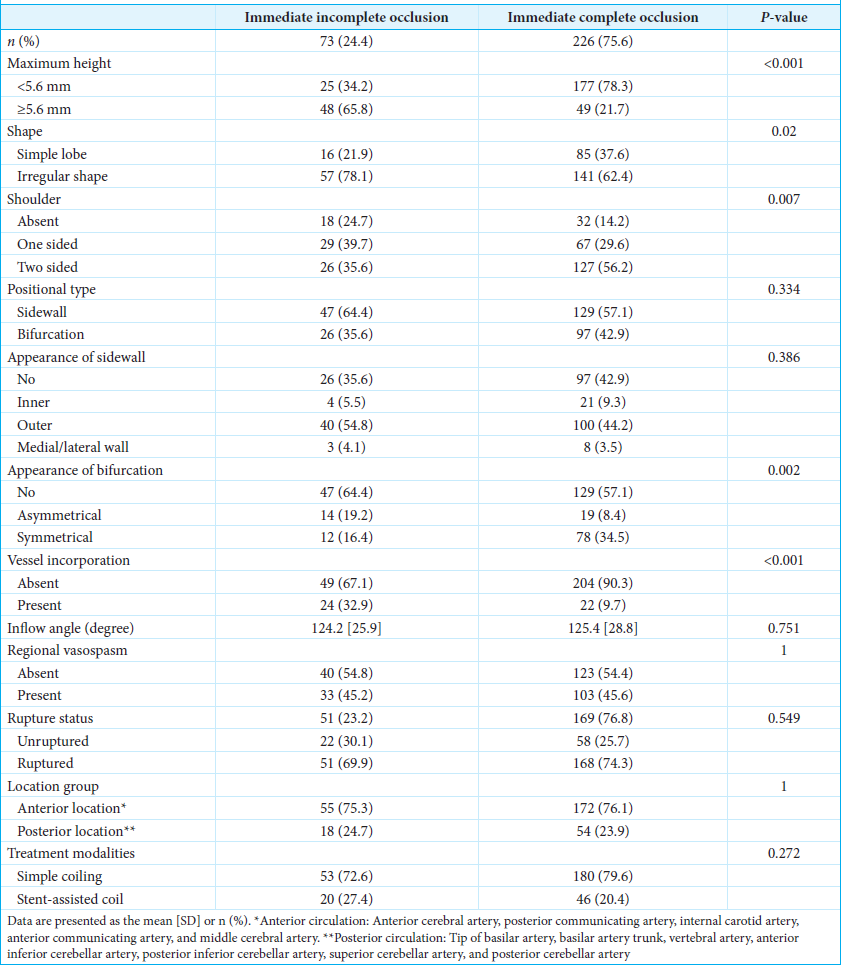

The optimal cutoff point of maximum height for predicting immediate incomplete occlusion was 5.6 mm, with a sensitivity of 65.7% and a specificity of 78.3%. The distributions of predictors and immediate endovascular treatment outcomes are presented in

Three independent factors predictive of immediate incomplete occlusion were identified in the final multivariable logistic regression model; these were maximum height, shoulder, and parent vessel incorporation [

DISCUSSION

The predictors of immediate incomplete occlusion after coil embolization of wide-necked aneurysms have not been clarified to date. The present study shows that angiographic morphologies of wide-necked aneurysms are internally valid in predicting immediate incomplete occlusion after coil or stent-assisted embolization. The model that included aneurysm height ≥5.6 mm, absent two-sided shoulder, and presence of vessel incorporation demonstrated robust performance, supporting its usefulness for predicting treatment outcomes. The study findings can be useful for guiding treatment techniques and devices, determining the need for further treatment, and preparing the appropriate posttreatment follow-up plan.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to determine the predictors of immediate incomplete occlusion after coil or stent-assisted embolization in wide-necked aneurysms. We found two earlier studies assessing factors associated with immediate incomplete occlusion in cerebral aneurysms, but they were not specific to wide-necked type aneurysms.[

Our findings on the impact of aneurysm height ≥5.6 mm on immediate incomplete occlusion align with that of a previous study that reported lower occlusion rates in wide-necked aneurysms measuring ≥10 mm than in smaller-sized wide-necked aneurysms, although each aneurysm was densely packed.[

The presence of vessel incorporation by the neck of a wide-necked aneurysm was associated with a significantly higher risk of immediate incomplete occlusion in the present study. This could be explained through the challenge of avoiding the occlusion of the incorporated branch artery during coil embolization of such an aneurysm. Although utilizing stent-assisted techniques enhances the likelihood of successful coil embolization and achieving more comprehensive packing in this context,[

The shape of the aneurysm, aneurysm angle, location at the side wall or bifurcation, symmetric and asymmetric bifurcation, and treatment modalities were not significantly associated with immediate incomplete occlusion in our study. A previous study showed that an irregular shape increased the risk of immediate incomplete occlusion after treatment; however, the study used the Woven EndoBridge (WEB) device, for which the selection of an appropriate device size depended on the wall and neck of an aneurysm, increasing the risk of incomplete occlusion.[

The effect of aneurysm angle, location at sidewall or bifurcation, or symmetric and asymmetric bifurcation on occlusion could not be supported in our study and had not also been reported previously, thus requiring further investigation. Simple coil embolization and stent-assisted coil embolization were used to treat wide-necked aneurysms in the present study. In all aneurysms, the first-line treatment was simple coil embolization. Stent assistance was performed only when the first coil could not be framed or stabilized within the aneurysm sac. Therefore, the rates of successful treatment of a wide-neck aneurysm could not be compared between these two modalities.

To our best knowledge, no study has specifically highlighted the effectiveness of predictors for coil embolization in wide-necked aneurysms, particularly in accurately discerning between immediate complete and incomplete occlusion. Our model demonstrated strong performance, affirming its usefulness in predicting immediate incomplete occlusion. However, this study also had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. The identification of the patients using the ICD-10 diagnosis codes from the hospital recording system may have caused over- or underestimation of the cases; however, this was minimized as the interventions were required, and all case diagnoses were reviewed. Second, we used the neck width of ≥4 mm, the dome-to-neck ratio of <2, or the aspect ratio of <2 to define wide-necked aneurysms, as no standard definitions have been established to date . Third, the occlusion outcome may depend on the experiences of neuro-interventionists and a team of neuro-interventionists performed all procedures in our study. The results of occlusion may be different from those of other studies. Fourth, as the angiographic morphologies of wide-necked aneurysms were identified based on available projection views in the imaging studies, certain morphologies may not have been adequately captured, affecting the accuracy of identification. However, efforts were made to minimize this limitation by achieving consensus among the reviewers. Finally, the findings may have limited generalizability due to the retrospective and single-center design; however, the morphologies of wide-necked aneurysms in our study were not obviously different from those in previous studies. Further research is warranted to examine treatment outcomes in the high-risk group and to conduct long-term follow-up after treatment.

CONCLUSION

The angiographic morphologies of wide-necked aneurysms accurately predict immediate incomplete occlusion after coil- or stent-assisted embolization. The model that includes aneurysm height ≥5.6 mm, absence of two-sided shoulders, and presence of vessel incorporation demonstrated strong performance, confirming its usefulness in predicting treatment outcomes. Wide-necked aneurysms with these characteristics should be approached with caution during endovascular treatment, and alternative techniques and devices should be explored to minimize the risk of immediate incomplete occlusion.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Human Research Ethics Committee Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, number REC.67-075-7-1, dated February 5, 2024.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent was not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

References

1. Al Saiegh F, Velagapudi L, Khanna O, Sweid A, Mouchtouris N, Baldassari MP. Predictors of aneurysm occlusion following treatment with the WEB device: Systematic review and case series. Neurosurg Rev. 2022. 45: 925-36

2. Baharoglu MI, Lauric A, Gao BL, Malek AM. Identification of a dichotomy in morphological predictors of rupture status between sidewall-and bifurcation-type intracranial aneurysms: Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2012. 116: 871-81

3. Baharoglu MI, Schirmer CM, Hoit DA, Gao BL, Malek AM. Aneurysm inflow-angle as a discriminant for rupture in sidewall cerebral aneurysms. Stroke. 2010. 41: 1423-30

4. Decharin P, Churojana A, Aurboonyawat T, Chankaew E, Songsaeng D, Sangpetngam B. Success rate of simple coil embolization in wide-neck aneurysm with aneurysmal shoulder. Asian J Neurosurg. 2020. 15: 594-600

5. Feng X, Peng F, Miao Z, Tong X, Niu H, Zhang B. Procedural complications and factors influencing immediate angiographic results after endovascular treatment of small (<5 mm) ruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020. 29: 104624

6. Fernandez Zubillaga A, Guglielmi G, Viñuela F, Duckwiler GR. Endovascular occlusion of intracranial aneurysms with electrically detachable coils: Correlation of aneurysm neck size and treatment results. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994. 15: 815-20

7. Fiorella D, Arthur AS, Chiacchierini R, Emery E, Molyneux A, Pierot L. How safe and effective are existing treatments for wide-necked bifurcation aneurysms? Literature-based objective performance criteria for safety and effectiveness. J NeuroInterv Surg. 2017. 9: 1197-201

8. Han YF, Jiang P, Tian ZB, Chen XH, Liu J, Wu ZX. Risk factors for repeated recurrence of cerebral aneurysms treated with endovascular embolization. Front Neurol. 2022. 13: 938333

9. Hendricks BK, Yoon JS, Yaeger K, Kellner CP, Mocco J, De Leacy RA. Wide-neck aneurysms: Systematic review of the neurosurgical literature with a focus on definition and clinical implications. J Neurosurg. 2019. 133: 159-65

10. Hope JK, Byrne JV, Molyneux AJ. Factors influencing successful angiographic occlusion of aneurysms treated by coil embolization. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999. 20: 391-9

11. Jang CK, Chung J, Lee JW, Huh SK, Son NH, Park KY. Recurrence and retreatment of anterior communicating artery aneurysms after endovascular treatment: A retrospective study. BMC Neurol. 2020. 20: 287

12. Jo KI, Yang NR, Jeon P, Kim KH, Hong SC, Kim JS. Treatment outcomes with selective coil embolization for large or giant aneurysms: Prognostic implications of incomplete occlusion. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2018. 61: 19-27

13. Johnston SC, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Lawton MT, Duckwiler GR, Gress DR. Predictors of rehemorrhage after treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms: The Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture after Treatment (CARAT) study. Stroke. 2008. 39: 120-5

14. Kawabata Y, Nakazawa T, Fukuda S, Kawarazaki S, Aoki T, Morita T. Endovascular embolization of branch-incorporated cerebral aneurysms. Neuroradiol J. 2017. 30: 600-6

15. Khumtong R, Thuncharoenkankha T, Riabroi K, Sakarunchai I, Wichaitum J, Liabsuetrakul T. Changes in modified Raymond-Roy classification occlusion classes and predictors of recurrence-free survival in patients with intracranial aneurysms after endovascular coil embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2023. 34: 685-93

16. Kim BM, Park SI, Kim DJ, Kim DI, Suh SH, Kwon TH. Endovascular coil embolization of aneurysms with a branch incorporated into the sac. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. 31: 145-51

17. Kole MK, Pelz DM, Kalapos P, Lee DH, Gulka IB, Lownie SP. Endovascular coil embolization of intracranial aneurysms: Important factors related to rates and outcomes of incomplete occlusion. J Neurosurg. 2005. 102: 607-15

18. Korja M, Kivisaari R, Rezai Jahromi B, Lehto H. Natural history of ruptured but untreated intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2017. 48: 1081-4

19. Mascitelli JR, Moyle H, Oermann EK, Polykarpou MF, Patel AA, Doshi AH. An update to the Raymond-Roy occlusion classification of intracranial aneurysms treated with coil embolization. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015. 7: 496-502

20. Mendenhall SK, Sahlein DH, Wilson CD. The natural history of coiled cerebral aneurysms stratified by Modified Raymond-Roy occlusion classification. World Neurosurg. 2019. 128: e417-26

21. Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, Clarke M, Sneade M, Yarnold JA. International subarachnoid aneurysm trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005. 366: 809-17

22. Morita A, Fujiwara S, Hashi K, Ohtsu H, Kirino T. Risk of rupture associated with intact cerebral aneurysms in the Japanese population: A systematic review of the literature from Japan. J Neurosurg. 2005. 102: 601-6

23. Ng P, Khangure MS, Phatouros CC, Bynevelt M, ApSimon H, McAuliffe W. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: Analysis of midterm angiographic and clinical outcomes. Stroke. 2002. 33: 210-7

24. Ohkuma H, Tsurutani H, Suzuki S. Incidence and significance of early aneurysmal rebleeding before neurosurgical or neurological management. Stroke. 2001. 32: 1176-80

25. Raymond J, Guilbert F, Weill A, Georganos SA, Juravsky L, Lambert A. Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils. Stroke. 2003. 34: 1398-403

26. Rinkel GJ, Djibuti M, Algra A, van Gijn J. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: A systematic review. Stroke. 1998. 29: 251-6

27. Santos MP dos, Sabri A, Dowlatshahi D, Bakkai AM, Elallegy A, Lesiuk H. Survival analysis of risk factors for major recurrence of intracranial aneurysms after coiling. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015. 42: 40-7

28. Steiner T, Juvela S, Unterberg A, Jung C, Forsting M, Rinkel G. European Stroke Organization Guidelines for the management of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013. 35: 93-112

29. Tamatani S, Ito Y, Koike T, Abe H, Kumagai T, Takeuchi S. Evaluation of the stability of intracranial aneurysms occluded with Guglielmi detachable coils. Interv Neuroradiol. 2001. 7: 143-8

30. Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, Rinkel GJ. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011. 10: 626-36