- Department of NeuroScience, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY 11501, USA

Correspondence Address:

Nancy E. Epstein

Department of NeuroScience, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY 11501, USA

DOI:10.4103/2152-7806.156556

Copyright: © 2015 Epstein NE. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.How to cite this article: Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R. C5 Nerve root palsies following cervical spine surgery: A review. Surg Neurol Int 07-May-2015;6:

How to cite this URL: Epstein NE, Hollingsworth R. C5 Nerve root palsies following cervical spine surgery: A review. Surg Neurol Int 07-May-2015;6:. Available from: http://surgicalneurologyint.com/surgicalint_articles/c5-nerve-root-palsies-following-cervical-spine-surgery/

Abstract

Background:Cervical C5 nerve root palsies may occur in between 0% and 30% of routine anterior or posterior cervical spine operations. They are largely attributed to traction injuries/increased cord migration following anterior/posterior decompressions. Of interest, almost all studies cite spontaneous resolution of these deficits without surgery with 3–24 postoperative months.

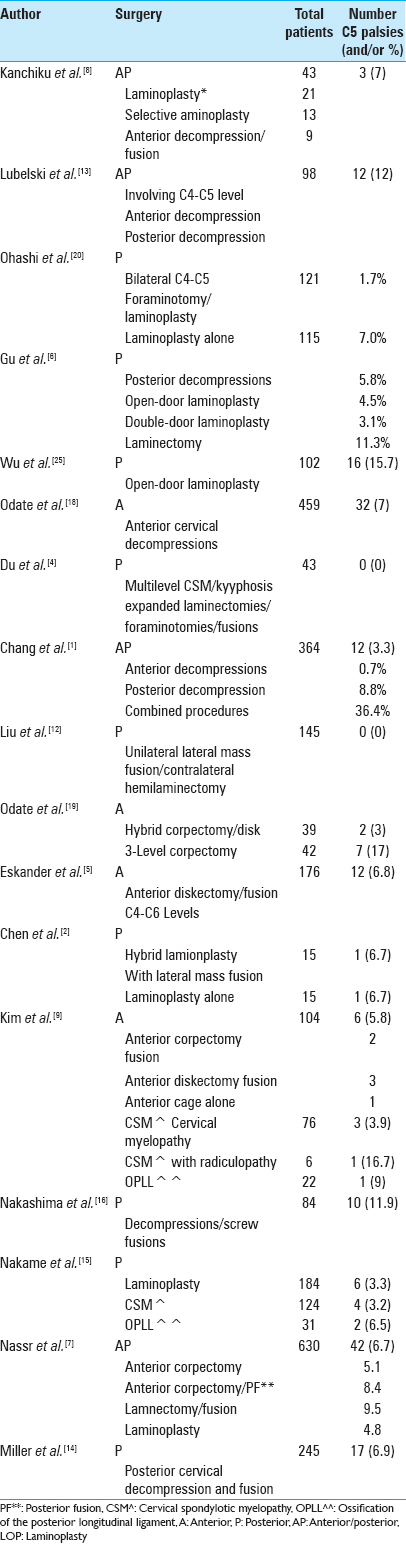

Methods:Different studies cite various frequencies for C5 root palsies following anterior or posterior cervical spine surgery. In their combined anterior/posterior series involving C4-C5 level decompressions, Libelski et al. cited up to a 12% incidence of C5 palsies. In Gu et al. series, C5 root palsies occurred in 3.1% of double-door laminoplasty, 4.5% of open-door laminoplasty, and 11.3% of laminectomy. Miller et al. observed an intermediate 6.9% frequency of C5 palsies followed by posterior cervical decompressions and fusions (PCDF).

Results:Gu et al. also identified multiple risk factors for developing C5 palsies following posterior surgery; male gender, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), narrower foramina, laminectomy, and marked dorsal spinal cord drift. Miller et al. also identified an average $1918 increased cost for physical/occupational therapy for patients with C5 palsies.

Conclusions:The incidence of C5 root deficits for anterior/posterior cervical surgery at C4-C5 was 12% in one series, and ranged up to 11.3% for laminectomies, while others cited 0–30%. Although identification of preoperative risk factors for C5 root deficits may help educate patients regarding these risks, there is no clear method for their avoidance at this time.

Keywords: Anterior surgery, cervical, C5 root palsies, C4-C5 surgery, factors, posterior surgery, risk

INTRODUCTION

The risk of C5 palsies occurring following anterior, posterior, or circumferential spine surgery varies from 0% to 30%.[

RISK OF C5 PALSY WITH ANTERIOR CERVICAL DECOMPRESSION

C5 palsy in 32 patients undergoing extremely wide/asymmetric anterior decompression

Of 459 patients having anterior decompression/fusion at the C4-C5 level for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM), Odate et al. found that 32 (7%) experienced postoperative C5 palsies [Tables

The frequency of C5 root palsies utilizing different anterior cervical operations for csm; risk of C5 palsy lower with multilevel diskectomies

Shamjii et al. compared the safety/efficacy of multiple anterior cervical approaches (decompressions/fusions) addressing CSM (e.g. excluding ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament [OPLL], single level CSM) [Tables

Hybrid decompression/fusion vs. Plated three-level corpectomy for 4-segment CSM

In 81 patients with 4-level CSM/kyphosis followed for at least 2 years, Odate et al. explored the efficacy/morbidity of hybrid decompressions/fusions (39 patients) vs. plated 3-level anterior corpectomy/fusion (ACF) (42 patients) [Tables

Correlation between preoperative spinal cord rotation and postoperative C5 palsy for anterior cervical discectomy/fusion between the c4-c6 levels

In 176 patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy/fusion (ACDF) between the C4-C6 levels, Eskander et al. correlated the degree of rotation of the cervical cord on MR scans with the 6.8% incidence of postoperative C5 palsies [Tables

Analysis of C5 palsies after anterior cervical surgery

In Kim et al. series of 104 patients with CSM, cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy (CSM/R), and/or OPLL (vs. another 30 with radiculopathy only), 6 (5.8%) developed C5 palsies [Tables

Complications with three alternative anterior decompression/fusion techniques for CSM

When Liu et al. evaluated multilevel ACDF vs. hybrid construct vs. long corpectomy performed in 286 patients (166 M/120 F; average age 53.8 (range 33–74) years), 61% exhibited perioperative complications; graft migration/collapse/dislodgement, hoarseness, dysphagia, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistulas, wound infections, and C5 palsies [Tables

RISKS OF C5 PALSY WITH ANTERIOR VS. POSTERIOR CERVICAL SURGERY

C5 root injuries with anterior and posterior surgery in CSM patients averaging 79 years of age

Kanchiku et al. reviewed the frequency of C5 root injuries in 43 consecutive patients averaging 79 years of age undergoing cervical spine surgery for CSM [Tables

Comparing risks of C5 palsy in anterior ‘skip’ corpectomy vs. Posterior surgery for spondylotic myelopathy

Qian et al. compared the efficacy of multilevel anterior “skip” corpectomy vs. posterior cervical decompressions for 3 level CSM [

Comparable rates of C5 palsy with anterior vs. Posterior cervical surgery

Lawrence et al. evaluated the pros and cons of anterior vs. posterior cervical surgical alternatives to address CSM involving more than 2 levels [Tables

Quantitative measures and frequency of c5 palsy with anterior vs. posterior cervical surgery: Assessment of risk factors and correlation with quality of life measures

Chang et al. assessed the relative risk/frequency of C5 palsy following 364 anterior vs. posterior cervical surgery, and related this to the quality of life [Tables

The frequency of C5 palsy after multilevel anterior or posterior cervical surgery

Nassr et al. cited a 0–30% incidence of C5 palsies reported in the literature, but found 42 (6.7%) instances of C5 palsies following 630 (292 females/338 males; average age 58 years) consecutive multilevel ACF with/without posterior fusions vs. laminectomy/fusion or laminoplasty in their own series [Tables

FREQUENCY OF C5 PALSIES WITH POSTERIOR CERVICAL SURGERY

C-5 palsy following posterior cervical decompressions/pedicle screw fusions

Nakashima et al. evaluated the unique radiographic risk factors (e.g. utilizing X-ray, MRI, computed tomography [CT]) for 10 (11.9%) of 84 (average age 60.1 years) patients who developed C5 palsies after undergoing posterior cervical decompressions/pedicle screw fusions [Tables

C-5 palsy following posterior cervical decompressions/vertex rod-eyelet spinous process fusion (without lateral mass screws)

In Epstein's series (in preparation), 3 (3.3%) of 92 patients undergoing 1-3 level laminectomies (mean 2.5)/and 5-9 level posterior instrumented fusions (average 7.6 level vertex rod/eyelet/braided cable/spinous process fusions) for CSM/OPLL developed delayed postoperative C5 palsies [Tables

C5 palsy with open-door vs. French-door laminoplasty for CSM

Wang et al. compared the relative efficacy/risks/complications of performing open-door laminoplasty (ODL) vs. French-door laminoplasty (FDL) for treating CSM. Four comparative trials were studied [

C5 root palsy following expansile open-door laminoplasty forCSM

Wu et al. retrospectively analyzed the risk factors resulting in the development of C5 palsies following open-door laminoplasties for CSM [Tables

More C5 root palsies following laminectomy and fusion for csm vs. Modified plate-only open-door laminoplasty for CSM

Yang et al. evaluated the extent of decompression and avoidance of complications (including C5 root palsies) for 141 CSM patients undergoing modified plate-only laminoplasty vs. laminectomy and fusion [Tables

RISK FACTORS, EARLY DETECTION, PREDICTION AND PREVENTION OF C5 PALSIES

Risk factors for C5 palsy; cervical laminectomy/fusion width and extent of dorsal cord migration

Radcliff et al. evaluated 17 patients with CSM/OPLL who developed C5 palsies following cervical laminectomy/fusion (CLF) accompanied by wide MR-documented laminectomy troughs [Tables

Predicting C5 palsy using preoperative anatomic measurements

Lubelski et al. evaluated whether the incidence of C5 root palsies could be predicted utilizing preoperative anterior posterior canal diameters (APD), foraminal diameters (FD), and/or cord-lamina angles (CLA) [Tables

Detection and prevention of C5 nerve root palsies after cervical spine decompressions

Utilizing the PubMed, Embase, and Medline databases, Guzman et al. found 60 articles that cited C5 palsies occurring after cervical spine surgery [Tables

RISK FACTORS AND SURGICAL MEASURES TO AVOID C5 ROOT PALSIES

Posterior cervical surgery; incidence/risk factors correlating with C5 palsy

Gu et al. systematically utilized the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases to evaluate the incidence/risk factors contributing to C5 palsy following posterior cervical decompressive surgery [Tables

Efficacy of prophylactic c4-C5 foraminotomy to avoid c5 root injuries following open-door cervical laminoplasty

Over a 2-year period, Ohashi et al. prospectively determined that C5 root injuries could be minimized by prophylactically performing bilateral C4-C5 foraminotomies during open-door cervical laminoplasties [Tables

Enlarged laminectomy with lateral mass screw fixation eliminated C5 palsy for multilevel csm with kyphosis

For 43 patients (28 M/15 F; average age 59.6 years) with multilevel CSM/kyphosis, Du et al. found performing multilevel expanded laminectomies/foraminal decompressions (average 3.97 levels) with lateral mass screw fixation reduced the incidence of instrumentation failures and C5 palsies and to zero [Tables

Hemilaminectomy/unilateral lateral mass fusion limits C5 root injury in cervical OPLL surgery

In theory, following typical cervical laminectomy or laminoplasty, excessive dorsal cord migration contributes to C5 palsies. Liu et al., therefore, performed unilateral hemilaminectomy with contralateral lateral mass fusion in 146 myelopathic OPLL patients to decompress the cord/maintain stability, and reduce the extent of dorsal cord migration, yielding a 0% incidence of C5 palsies [Tables

Use of posterior hybrid technique for treatment of segmental instability in cervical opll failed to limit C5 palsies

Chen et al. compared outcomes for 15 cervical OPLL patients with segmental instability (SI) and frequent MR-documented high-signal intensity zones (HIZ; typically at SI levels) managed with laminoplasty/lateral mass screw fixation (hybrid model) vs. 15 OPLL patients without SI treated with laminoplasty alone [Tables

USE OF INTRAOPERATIVE NEURAL MONITORING TO DETECT C5 PALSIES

C5 palsy using ionm transcranial motor evoked potentials

Nakame et al. correlated postoperative C5 root palsies with intraoperative changes in transcranial motor evoked potentials (MEP; deltoid, biceps, and triceps muscles bilaterally) occurring during 184 laminoplasties [Tables

C5 palsies in cervical spine surgery despite intraoperative monitoring

Currier reviewed the “etiology, risk factors, prevention, and treatment of C5 palsy” occurring during cervical surgery despite the use of IONM [

COST AND QUALITY OF LIFE WITH C5 PALSY AFTER POSTERIOR SURGERY

Incidence, cost, and quality of life with C5 palsy after posterior cervical decompression and fusion

Miller et al. looked at the quality-of-life/costs of C5 palsy following posterior cervical decompression and fusion (PCDF).[

CONCLUSION

The frequency of C5 palsies reportedly varies from 0% to 30%, with many focusing on a risk of 3.1–12%. The presence of preoperative MR-documented HIZ: C3-C5 in the cord opposite the C4-C5 level, surgery (e.g. either anterior or posterior) at the C4-C5 level, and dorsal cord migration all constitute significant risk factors for developing postoperative C5 palsies. Although this review discusses the frequency of C5 root palsies, there appears to be no clear-cut method for avoiding these injuries. Fortunately, the majorities resolve within 3–24 postoperative months without conservative treatment alone.

References

1. Chang PY, Chan RC, Tsai YA, Huang WC, Cheng H, Wang JC. Quantitative measures of functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with C5 palsy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013. 76: 378-84

2. Chen Y, Chen D, Wang X, Yang H, Liu X, Miao J. Significance of segmental instability in cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and treated by a posterior hybrid technique. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013. 133: 171-7

3. Currier BL. Neurological complications of cervical spine surgery: C5 palsy and intraoperative monitoring. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012. 37: E328-34

4. Du W, Zhang P, Shen Y, Zhang YZ, Ding WY, Ren LX. Enlarged laminectomy and lateral mass screw fixation for multilevel cervical degenerative myelopathy associated with kyphosis. Spine J. 2014. 14: 57-64

5. Eskander MS, Balsis SM, Balinger C, Howard CM, Lewing NW, Eskander JP. The association between preoperative spinal cord rotation and postoperative C5 nerve palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012. 94: 1605-9

6. Gu Y, Cao P, Gao R, Tian Y, Liang L, Wang C. Incidence and risk factors of C5 palsy following posterior cervical decompression: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2014. 9: e101933-

7. Guzman JZ, Baird EO, Fields AC, McAnany SJ, Qureshi SA, Hecht AC. C5 nerve root palsy following decompression of the cervical spine: A systematic evaluation of the literature. Bone Joint J. 2014. 96-B: 950-5

8. Kanchiku T, Imajo Y, Suzuki H, Yoshida Y, Nishida N, Taguchi T. Results of surgical treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy in patients aged 75 years or more: A comparative study of operative methods. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014. 134: 1045-50

9. Kim S, Lee SH, Kim ES, Eoh W. Clinical and radiographic analysis of c5 palsy after anterior cervical decompression and fusion for cervical degenerative disease. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014. 27: 436-41

10. Lawrence BD, Jacobs WB, Norvell DC, Hermsmeyer JT, Chapman JR, Brodke DS. Anterior versus posterior approach for treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013. 38: S173-82

11. Liu Y, Qi M, Chen H, Yang L, Wang X, Shi G. Comparative analysis of complications of different reconstructive techniques following anterior decompression for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Eur Spine J. 2012. 21: 2428-35

12. Liu K, Shi J, Jia L, Yuan W. Surgical technique: Hemilaminectomy and unilateral lateral mass fixation for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013. 471: 2219-24

13. Lubelski D, Derakhshan A, Nowacki AS, Wang JC, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC. Predicting C5 palsy via the use of preoperative anatomic measurements. Spine J. 2014. 14: 1895-901

14. Miller JA, Lubelski D, Alvin MD, Benzel EC, Mroz TE. C5 palsy after posterior cervical decompression and fusion: Cost and quality-of-life implications. Spine J. 2014. 14: 2854-60

15. Nakamae T, Tanaka N, Nakanishi K, Kamei N, Izumi B, Fujioka Y. Investigation of segmental motor paralysis after cervical laminoplasty using intraoperative spinal cord monitoring with transcranial electric motor-evoked potentials. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2012. 25: 92-8

16. Nakashima H, Imagama S, Yukawa Y, Kanemura T, Kamiya M, Yanase M. Multivariate analysis of C-5 palsy incidence after cervical posterior fusion with instrumentation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012. 17: 103-10

17. Nassr A, Eck JC, Ponnappan RK, Zanoun RR, Donaldson WF, Kang JD. The incidence of C5 palsy after multilevel cervical decompression procedures: A review of 750 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012. 37: 174-8

18. Odate S, Shikata J, Yamamura S, Soeda T. Extremely wide and asymmetric anterior decompression causes postoperative C5 palsy: An analysis of 32 patients with postoperative C5 palsy after anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013. 38: 2184-9

19. Odate S, Shikata J, Kimura H, Soeda T. Hybrid decompression and fixation technique versus plated three-vertebra corpectomy for four-segment cervical myelopathy: Analysis of 81 cases with a minimum 2-year follow-up. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013. p.

20. Ohashi M, Yamazaki A, Watanabe K, Katsumi K, Shoji H. Two-year clinical and radiological outcomes of open-door cervical laminoplasty with prophylactic bilateral C4-C5 foraminotomy in a prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014. 39: 721-7

21. Qian L, Shao J, Liu Z, Cheng L, Zeng Z, Jia Y. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of anterior ‘skip’ corpectomy versus posterior decompression in the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014. 9: 63-

22. Radcliff KE, Limthongkul W, Kepler CK, Sidhu GD, Anderson DG, Rihn JA. Cervical laminectomy width and spinal cord drift are risk factors for postoperative C5 palsy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2014. 27: 86-92

23. Shamji MF, Massicotte EM, Traynelis VC, Norvell DC, Hermsmeyer JT, Fehlings MG. Comparison of anterior surgical options for the treatment of multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013. 38: S195-209

24. Wang L, Wang Y, Yu B, Li Z, Liu X. Open-door versus French-door laminoplasty for the treatment of cervical multilevel compressive myelopathy. J Clin Neurosci. 2015. 22: 450-5

25. Wu FL, Sun Y, Pan SF, Zhang L, Liu ZJ. Risk factors associated with upper extremity palsy after expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy. Spine J. 2014. 14: 909-15

26. Yang L, Gu Y, Shi J, Gao R, Liu Y, Li J. Modified plate-only open-door laminoplasty versus laminectomy and fusion for the treatment of cervical stenotic myelopathy. Orthopedics. 2013. 36: e79-87